Shadows Join Jupiter, Reading the Rings, Diminishing Meteors, a Mounting Moon Sips Earth’s Shadow, and Venus Gleams at Dawn!

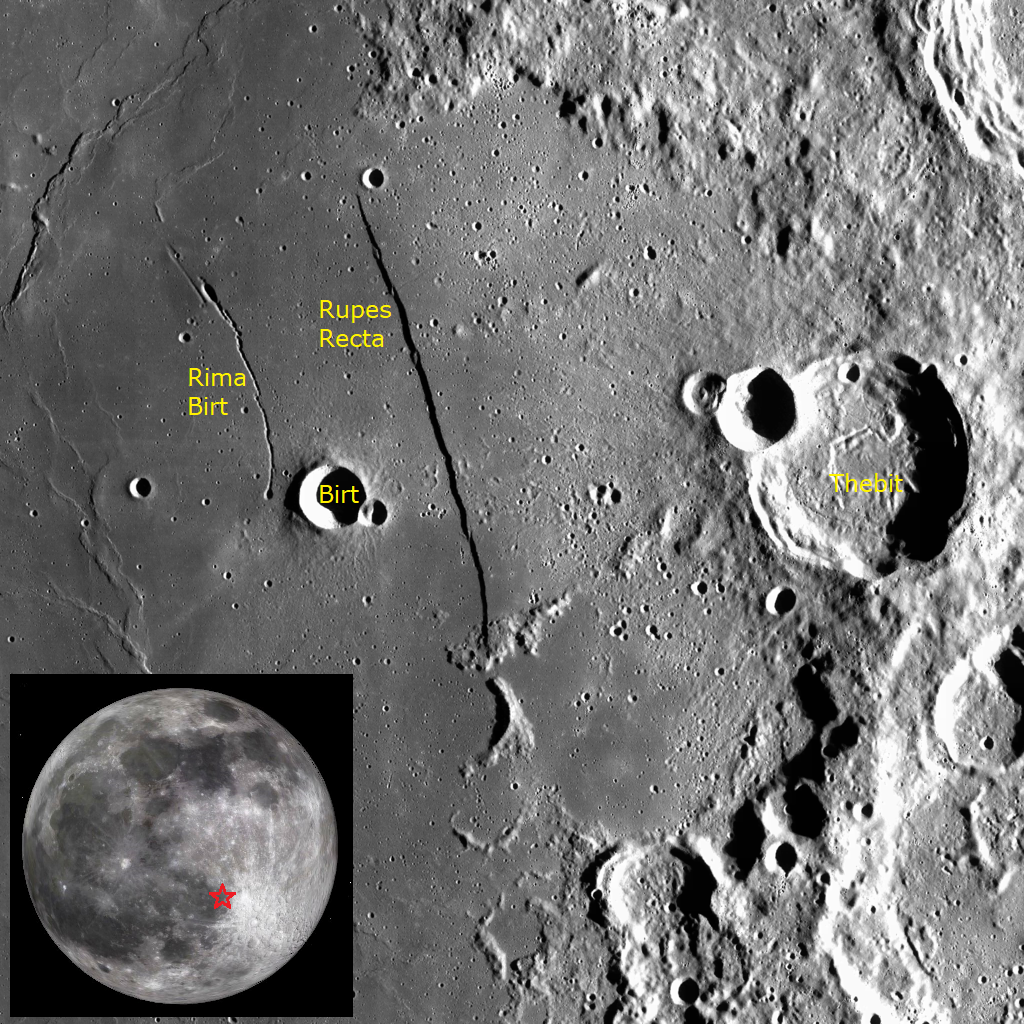

This image of the Lunar Straight Wall or Rupes Recta in Mare Nubium was captured by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. While the feature can be seen through binoculars, a backyard telescope will reveal more detail. (Adapted from NASA LRO)

Hello, October Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of October 22nd, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! I’m proud of my book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope. It’s a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The recent Orionids meteor shower will taper off early this week. Meanwhile, the moon will wax fuller and shine with increasing brightness during evening and late night this week – culminating in a full, partially eclipsed moon on Saturday. Jupiter’s disk will sport shadows, we dive into Saturn’s rings, the ice giant planets chase the gas giants, and Venus will gleam at sunrise. Read on for your Skylights!

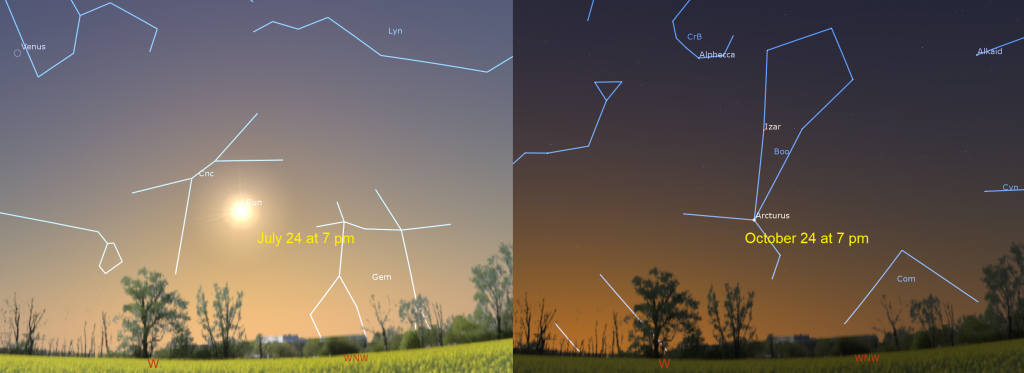

Ghost of the Summer Sun

During the week before Halloween, especially Oct 24-25, the bright star Arcturus becomes “the Ghost of the Summer Sun”! That’s because its sits at about the same altitude and azimuth in the sky that the sun did exactly four months earlier at the same time of the evening – in broad daylight, though.

Meteor Shower Update

We’re into meteor shower season! The Orionids Meteor Shower peaked in the Americas last night, Saturday, October 21. This shower’s broad peak of activity will last until about Tuesday, so keep an eye to the sky as the shower tapers off this week. Orionids will be streaking away from Orion, which is climbing the east in late evening.

Two weak showers derived from debris dropped by periodic comet 2P/Encke are ramping up, too. The Northern Taurids and Southern Taurids meteor showers have begun. They will slowly ramp up towards their peak nights in early November. This week, a meteor from either shower will be streaking away from a point in the sky near Jupiter.

The Moon

The moon will dominate the evening sky worldwide this week while it waxes towards full on Saturday. The early sunset time at mid-northern latitudes this week (about 6:20 pm at the latitude of Toronto) means that the moon will already be shining after dinner.

The waxing moon is a wonderful subject for close inspection in binoculars and backyard telescopes. The horizontal rays of sunlight striking the moon alongside the pole-to-pole terminator boundary that separates the moon’s lit and dark hemispheres, will throw into stark relief every hump, bump, boulder, hill, ridge, crater rim, and mountain – producing spectacular vistas under any magnification. And new features are revealed every night.

Tonight (Sunday) the moon will appear slightly more than half-illuminated because it passed its first quarter phase last night. The moon will continue to be gibbous – more than 50% illuminated – until November 5. At this part of the lunar month, the moon rises in mid-afternoon and shines until about midnight. While the sky darkens tonight, the planet Saturn will appear off to the moon’s left. Before long the bashful stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) will appear around the moon. They’re not very bright. On Sunday night the terminator will bisect the big circle of the Imbrium Basin that covers most of the moon’s northern hemisphere. Watch for subtle wrinkles on Imbrium’s otherwise quite smooth surface.

The terminator will also fall to the left (or lunar west) of Rupes Recta, also known as the Lunar Straight Wall. The rupes, the Latin word for “cliff”, is a north-south aligned fault scarp that extends for 110 km across the southeastern part of Mare Nubium, the dark patch in the lower third of the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere. The wall is visible as a straight line in good binoculars and backyard telescopes. It is most prominent a day or two after first quarter, and also on the days before the third quarter phase. For reference, the prominent crater Tycho, with its central mountain peak, is located due south of the Straight Wall. Depending on your time zone Tycho should appear as a dark circle with a bright peak tonight.

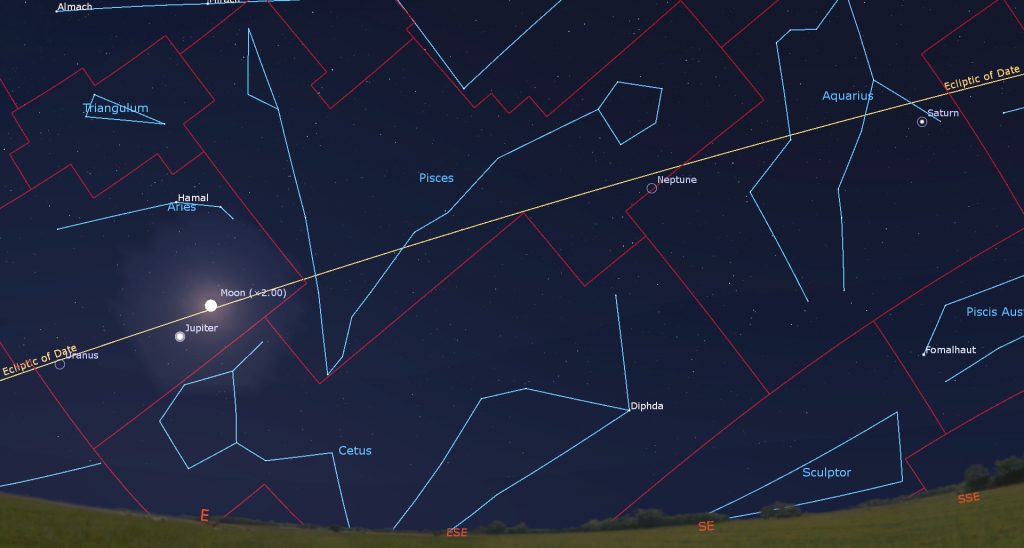

On Monday night, the moon will hop east to shine closer to Saturn, though still in Capricornus. Tuesday’s moon will shine in Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and to Saturn’s lower left (or celestial east). By then the entire Imbrium Basin will be lit up. Watch for the bright Jura mountain range that curls around “the Bay of Rainbows” Sinus Iridium on Mare Imbrium’s left side. On Wednesday night the very bright, 89%-illuminated moon will be gleaming near Neptune in eastern Aquarius – but that dim planet won’t be visible against the glare.

The nights starting on Wednesday will be particularly good for viewing the prominent crater Copernicus, which is located in eastern Oceanus Procellarum, the dark region located due south of Mare Imbrium and slightly northwest of the moon’s centre. This 800 million year old impact scar is visible with unaided eyes and binoculars – but telescope views will reveal many more interesting aspects of lunar geology. Several nights before the moon reaches its full phase, Copernicus exhibits heavily terraced edges due to slumping after the crater formed, an extensive ejecta blanket tossed outside the crater rim, a complex central mountain peak, and both smooth and rough terrain on the crater’s floor.

On Thursday and Friday the bright moon will swim with Cetus (the Whale) and then Pisces (the Fishes), easily outshining their stars. By then, Copernicus’ ragged ray system, which extends 800 km in all directions around the crater, will become prominent. Use high telescope magnification to look around Copernicus for small craters featuring bright floors and black haloes – impacts through Copernicus’ white ejecta that excavated dark Oceanus Procellarum basalt and the even deeper highlands white anorthosite.

The full moon of October will occur on Saturday, October 28 at 4:24 pm EDT, 1:24 pm PDT, or 20:24 Greenwich Mean Time. Everyone on Earth sees the same moon phase when their part of the world turns to face it. Full moons in October always shine in or near the stars of Cetus and Pisces and climb relatively high in the sky around midnight.

This full moon is traditionally called the Hunter’s Moon, Blood or Sanguine Moon. The Anishinaabe people of the Great Lakes region call it Binaakwe-giizis, the Falling Leaves Moon, or Mshkawji-giizis, the Freezing Moon. The Cree Nation of central Canada calls it Opimuhumowipesim, the Migrating Moon – the month when birds are migrating. The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois / Mohawk) of Eastern North America use Kentenha, the Time of Poverty Moon.

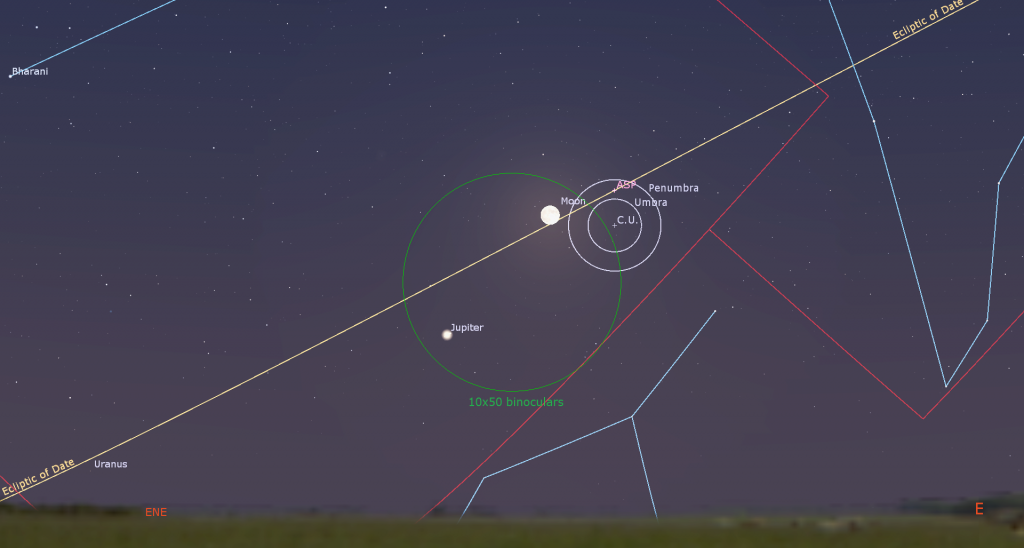

The moon is full when it is opposite to the sun in the sky, but it usually avoids the circular shadow that the solid Earth casts into space, known as the umbra. This full moon will dip its toes into Earth’s shadow, producing a partial lunar eclipse visible across Africa, Europe, and Asia. Observers there will see a small bite out the moon’s southern limb between 19:35 and 20:53 GMT, with a maximum of 12% of the moon’s diameter inside Earth’s shadow at 20:15 GMT. In the Americas, the moon will have already passed the shadow when it rises, but you may be able to watch some eclipse livestreams. Lunar eclipses are safe to photograph and view without eye protection. Wherever you are on Saturday night, watch for the bright planet Jupiter shining close enough to the lower left of the moon for them to share the view in binoculars.

The moon will end this week in eastern Aries (the Ram) and starting to wane in phase. A short time after the bright, still very full moon clears the treetops in the northeastern sky next Sunday evening, the planet Uranus will be situated less than three lunar diameters below it, or 1.6 degrees to the moon’s south-southeast. As the pair cross the night sky together, the moon’s easterly orbital motion will carry it farther from Uranus and diurnal rotation will shift the moon above the planet in the hours before dawn. While the blue, magnitude 5.6 ice giant planet is normally easy to see in binoculars and backyard telescopes, so much bright moonlight next door will make that difficult. Uranus will be occupying the sky between Jupiter and the bright Pleiades star cluster for some time, so look for the distant planet on nights when the moon isn’t around.

The Planets

The two gas giant planets will continue their reign over the evening sky this week, each accompanied by a much fainter ice giant planet. If you’ve been contemplating the purchase of a telescope, now would be a great time. Easy-to-find planets will shine after dusk from now until winter and some of the brightest galaxies, star clusters, and nebulae in the sky are available, too. (Well, except for moonlit weeks like this one.)

Saturn is a couple of months past its prime for this year, but it will continue to be well-placed for breath-taking telescope views until mid-January. The ringed planet’s medium-bright, yellowish dot will first appear in the lower part of the southeastern sky after sunset. It will climb to its highest point in the sky, due south, at about 9:30 pm local time, and then it will set in the west during the wee hours. The faint stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) will be sparkling to the left and right of Saturn, respectively – but their luster will be hindered by the bright moon. The bright trio of the Summer Triangle asterism stars will shine high above Saturn, though. If you have an unobstructed southern horizon, look for the very bright, white star Fomalhaut or Alpha Piscis Austrini (the Southern Fish) shining two fist diameters below Saturn. That star is only 25 light-years from our sun!

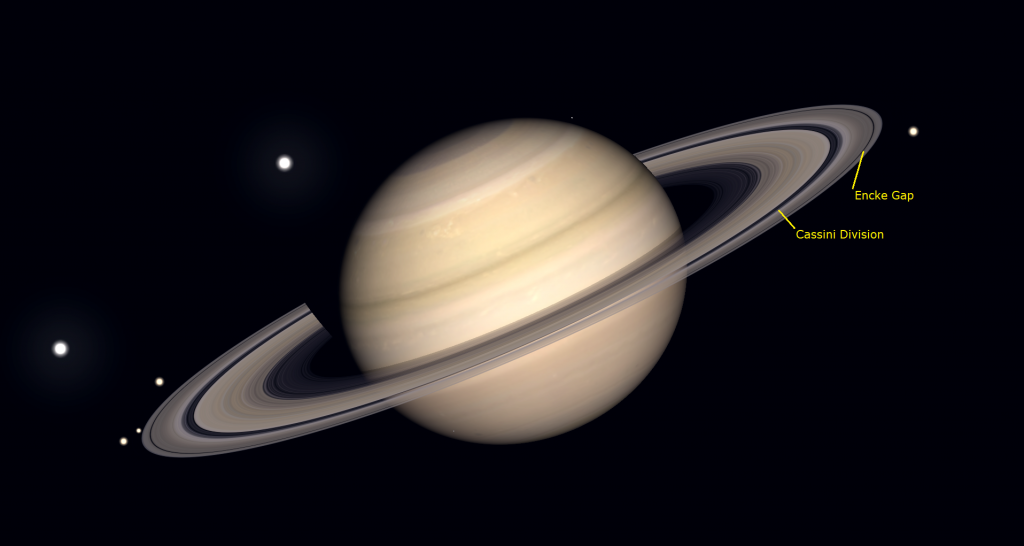

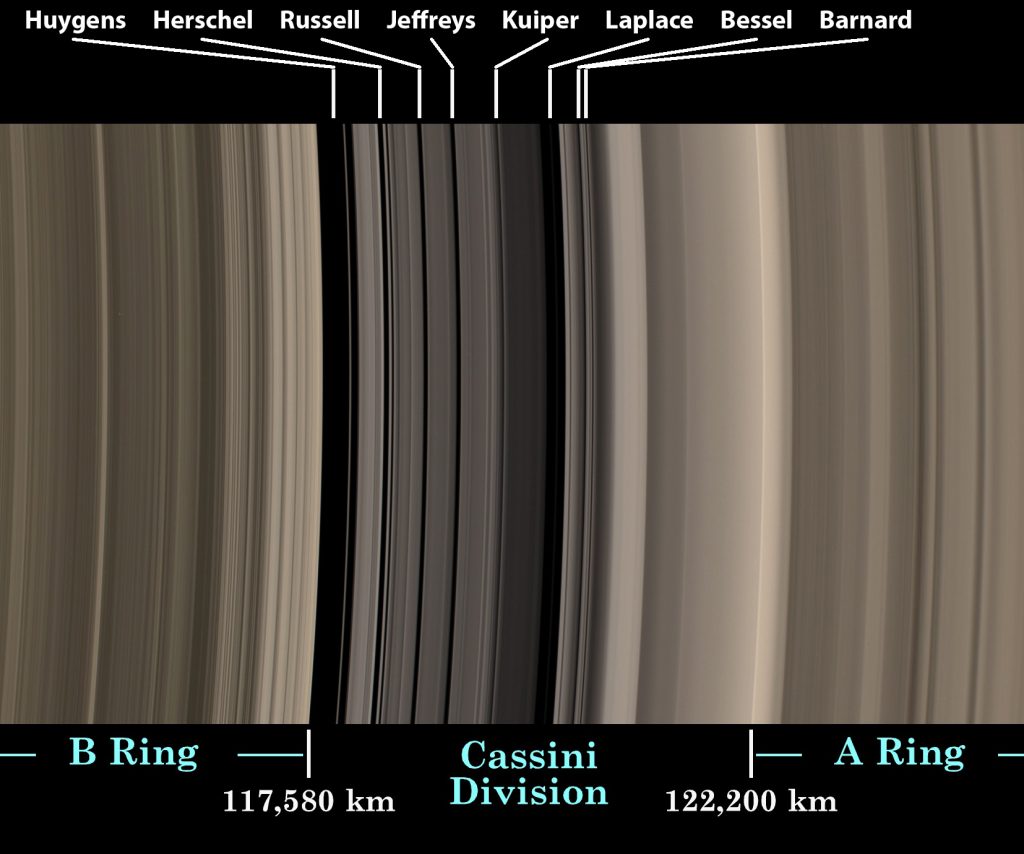

Any size, style, or brand of telescope will show Saturn’s beautiful rings. If your optics are of good quality and the air isn’t too turbulent, try to see the Cassini Division, a narrow gap that separates the large outer A Ring from the large inner B Ring. The A Ring is 14,600 km wide, the B Ring is 25,500 km wide, the 17,500 km-wide C Ring nestles inside B, and the 7,500 km-wide D Ring is inside that. The very narrow (30-500 km) F Ring that surrounds the A Ring is encircled by the 8,000 km-wide G Ring. The huge, but faint E Ring, 300,000 km wide, surrounds all the rest. It is sustained by frozen water that erupts from the geysers on Saturn’s moon Enceladus.

Though broad in size and highly reflective, the rings are very thin – ranging between 10 metres and 1 km top to bottom. The Cassini space mission weighed the ring system by diving between them and the planet and measuring the minute changes in gravity it felt. Close-up views of the rings reveal more minor rings and gaps between them, many of which are kept clear by tiny moonlets that orbit the planet. The outer edge of the A Ring is split by the 325-km-wide Encke Gap, which is shepherded by the small moon named Pan. Other gaps have been named for famous scientists.

A backyard telescope can also show the small wedge of dark shadow that is cast upon on the rings alongside of the eastern limb of the planet’s globe and faint belts of dark cloud that encircle Saturn. Remember to take long, lingering looks through the eyepiece – so that you can catch moments of perfect atmospheric clarity. Good binoculars can hint at the shape of Saturn’s rings, too.

From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves above, below, and alongside the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from upper right of Saturn (celestial west) tonight to the left of the planet (celestial east) next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks. You may be surprised at how many of them you can see through your telescope if you look closely.

The ice giant planet Neptune, currently about 730 times fainter than Saturn, follows the ringed planet across the sky each night. This week it will be lurking 2.5 fist diameters to Saturn’s left, or 25° to its celestial northeast. The diurnal rotation of the sky – the way things tilt as they cross from east to west – will cause Neptune to be lower than Saturn until 9:15 pm and then increasingly than Saturn higher after that. Magnitude 7.8 Neptune is visible in backyard telescopes, especially between dusk and 3 am local time, when the blue planet is highest. Good binoculars can show Neptune, too – if your sky is very dark. This week’s bright moonlight, and its visit with Neptune on Thursday, will make seeing Neptune tough this week.

Jupiter will reach its own peak visibility for the year next week. The extremely bright planet will rise in the east at around 6:45 pm local time this week and cross the sky all night long with its best telescope-viewing time commencing by 9 pm. The two brightest stars of Aries (the Ram), named Hamal and Sheratan, have been shining a generous fist’s diameter above the giant planet this year. Next year, Jupiter’s 12-year orbit will place it into Taurus (the Bull). For now, that winter constellation will follow Jupiter across the sky during the night. Keep an eye out for Jupiter gleaming above the western horizon around sunrise each morning.

Binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons in a line beside the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. All four moons will huddle to the east side of Jupiter on Thursday night.

A small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in mid-evening Eastern Time tonight (Sunday), Tuesday, Friday, and next Sunday night. It’ll appear around midnight on Thursday and Saturday morning, and before dawn on Monday and Saturday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Friday morning, October 27, Io’s small shadow will cross Jupiter’s equatorial region from 3:34 to 5:43 am EDT (or 07:34 to 09:43 GMT). Europa’s shadow will venture across Jupiter’s southern latitudes, with the Great Red spot, on Friday evening, October 27 from 6:42 to 9 pm EDT (or 22:42 to 01:00 GMT). Io’s shadow will cross again on Saturday night, October 28 from 10:03 pm to 12:12 am EDT (or 02:03 to 04:12 GMT on October 29). (These times may vary by a few minutes, and other time zones of the world will have their own crossings.)

Like Neptune following Saturn in evening, the planet Uranus is following Jupiter across the overnight sky. This week the blue-green ice giant planet will be positioned a fist’s diameter to Jupiter’s lower left (or 10° to the celestial east), just on the Aries side of its border with Taurus. The diurnal rotation of the sky will lift Uranus higher than Jupiter after 1:30 am local time. The bright little Pleiades star cluster will be located a shorter distance to Uranus’ left. Magnitude 5.6 Uranus is visible in both binoculars and small telescopes when a bright moon isn’t nearby. Uranus’ small coloured disk is a treat to see in a telescope. The best times for looking will start around 9:15 pm local time. This year, a pair of medium-bright stars named Botein and Al Butain IV (or Sigma and Zeta Arietis) are shining two finger widths above Uranus every evening. Since they are easy to see in binoculars, they can act as your guides.

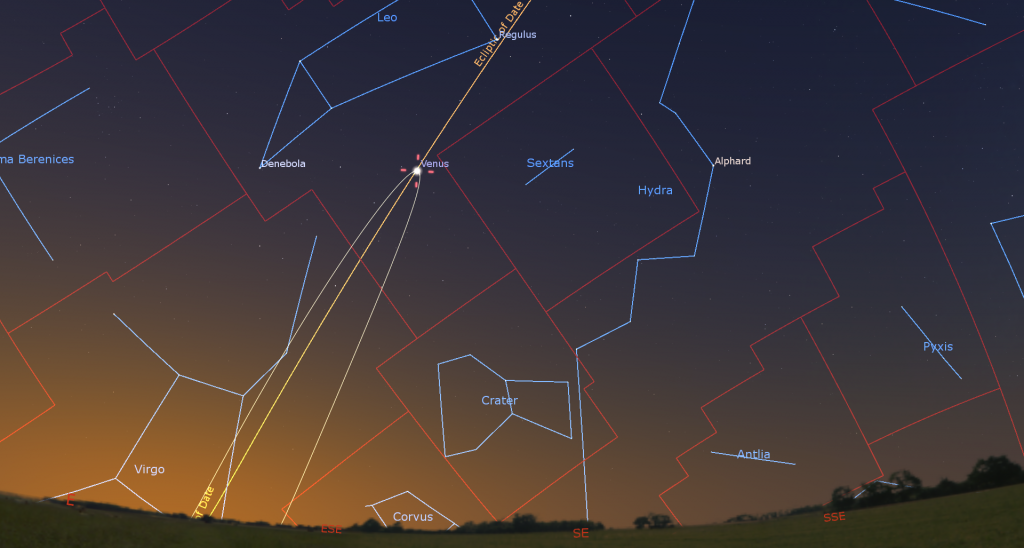

Venus and Jupiter will continue to gleam on opposite sides of the pre-dawn sky this week. If you head outside on a clear morning around 6:15 am local time, Venus and Jupiter will be positioned at about the same height in the sky, though Jupiter will be descending in the west while Venus is lifted higher in the east by Earth’s rotation. The bright stars of the winter constellations will shine between them in the southern sky.

From Monday to Tuesday, Venus will reach its greatest separation, 46.5 degrees west of the sun, for its current morning appearance. Every morning, the very bright, magnitude -4.5 planet will be shining in the eastern sky from the time it rises at about 3:40 a.m. local time until sunrise hides it. Viewed through a telescope this week, Venus will show a waxing, half-illuminated disk spanning 24.2 arc-seconds.

Mars and Mercury are both too near to the sun to be seen.

Some Double Stars for Moonlit Nights

Since the moon will stick around for the coming week, grab your binoculars and check out the moonlight-tolerant double stars I described last week here.

Morning Zodiacal Light

During autumn at mid-northern latitudes every year, the ecliptic extends nearly vertically upward from the eastern horizon before dawn. That geometry favors the appearance of the faint zodiacal light in the eastern sky for about half an hour before dawn on moonless mornings. Zodiacal light is sunlight scattered by interplanetary particles that are concentrated in the plane of the solar system – the same material that produces meteor showers. It is more readily seen in areas free of urban light pollution.

Between now and the full moon on October 28, try looking for the phenomenon as a broad wedge of faint light extending upwards from the eastern horizon and centered on the ecliptic. It will be strongest in the lower third of the sky, below the bright planet Venus. Try taking a long exposure photograph to capture the zodiacal light, but don’t confuse it with the Milky Way, which will be extending upwards nearby in the southern sky.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Friday, October 27 from 7:30 to 9:30 pm EDT, the in-person Astronomy Speakers Night program at the David Dunlap Observatory in Richmond Hill, Ontario will feature Dr. Xiaohan Wu of the Canadian Institute of Theoretical Astrophysics. She will speak on The Universe Seen in the Eyes of a Fast Radio Burst.After the presentation, participants will tour the observatory and see a demonstration of the 74” telescope pointed to an interesting celestial object for the visitors to view (weather permitting). More information is here and the registration link is at ActiveRH.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!

One Response

The full moon image of Copernicus was very interesting indeed. Perhaps because of the lack of shadows and excessive light at this phase, photos of the full moon attract little scientific interest. This one, however, shows the crater wall systems in remarkably intricate detail. Well done!