Spotty Jupiter, an Attractive Evening Moon, Hunting Orion’s Meteors, and Seeing Double!

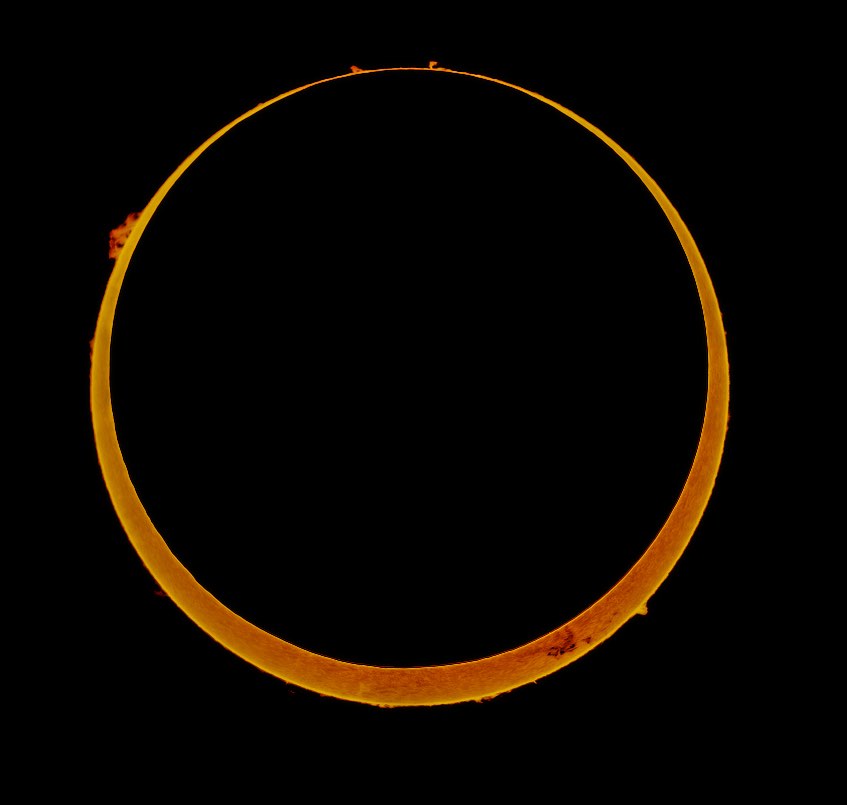

Andrea Girones of Ottawa captured this amazing image of Saturday’s annular solar eclipse from Albuquerque, New Mexico. She used a Lunt 40mm solar telescope, an ASI 174MM camera on a Skywatcher Star Adventurer tracker.

Hello, Autumn Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of October 15th, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! I’m proud of my book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope. It’s a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will return to shine prettily during evening this week, joining Jupiter, Saturn and the ice giant planets Uranus and Neptune. Meanwhile, we can enjoy some evening double and multiple stars with unaided eyes, binoculars, and telescopes, and the Orionids meteor shower will peak on the coming weekend. Read on for your Skylights!

Orionids Meteor Shower

We’ve entered meteor shower season! Over the next few months, Earth will experience several showers. My friend Blake Nancarrow created a very informative graph of meteor shower intensity throughout the year here, on his Lumpy Darkness blog.

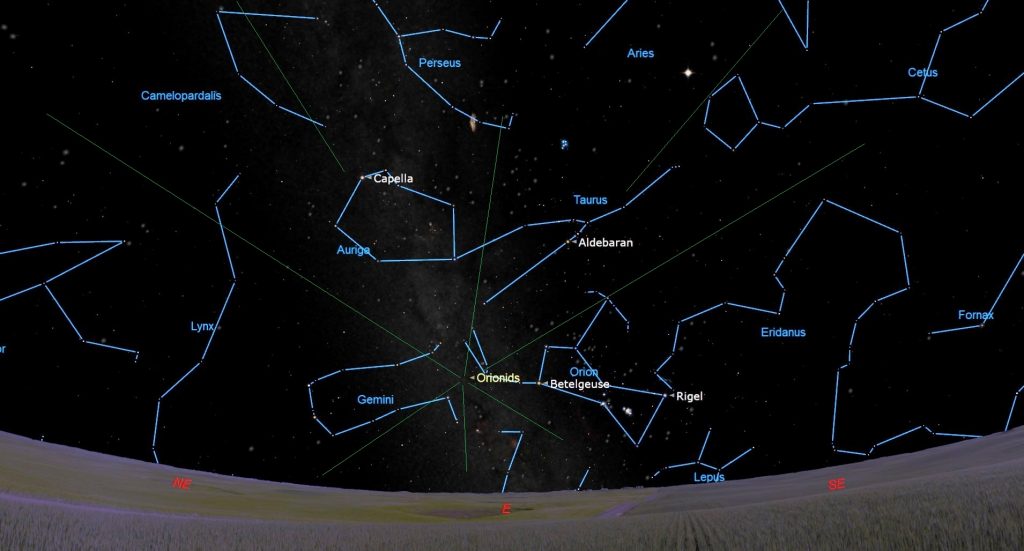

The excellent Orionids Meteor Shower, which is observable world-wide, happens every year between September 26 and November 22 while the Earth is plowing through a cloud of fine particles dropped by repeated past passages of the periodic comet designated 1P/Halley, or simply, Halley’s Comet. The Orionids (for short) will peak in the Americas on the evening of Saturday, October 21. Start watching for Orionids after dusk on Saturday night, and especially after the half-illuminated moon sets around 11:30 pm. The very best Orionids viewing time in the Americas will be before dawn on Sunday morning, when the sky overhead will be plowing directly into the particle field, generating as many as 10-20 meteors per hour. Although not especially numerous, Orionids are known for being bright and fast-moving.

The meteors can appear anywhere in the sky, but true Orionids will seem to be travelling in a direction away from a location in the sky called the radiant that is near the bright red star Betelgeuse in the constellation of Orion – giving this shower its name. This year, bright, Jupiter will shine overnight. The Orionids radiant will rise at about 10:30 pm – but up to half of the Orionids will be travelling downwards, and will therefore be blocked by your local horizon until Orion climbs higher. The most meteors will be seen before daybreak on Sunday, when the radiant will be highest in a dark sky. You will still see a reduced number of Orionids on Saturday before dawn and Sunday overnight, and fewer yet on the surrounding nights.

While the Orionids Shower will last until late November, the meteors will decrease in quantity every night after Saturday’s peak. The Orionids has a broad period of activity because the orbit of Halley’s Comet is tilted by only 17° from the plane of the Solar System, and it also crosses Earth’s orbit obliquely. Last year I posted top-down and edge-on views of the orbits showing that here. There’s a terrific, interactive, 3D meteor shower visualizing tool at https://www.meteorshowers.org/.

To see the most meteors, first check the weather forecast – you won’t see meteors if it’s cloudy. Get away from light-polluted, urban skies and find a dark site with plenty of open sky. If the moon is up, try to hide it behind a tree or building. Don’t bother using binoculars or a telescope for meteors – their fields of view are too narrow. Don’t focus your attention on the sky near the radiant because those meteors will be travelling towards you and will produce very short streaks. Instead, sweep the sky overhead.

To preserve your eyes’ dark adaptation, avoid the bright white light from phones or tablets. Red light is fine – so cover your device’s screen with red film or use its red mode. If the peak night forecast calls for clouds, try the nights before or the nights after. Good luck!

The Moon

The next two weeks of the lunar month will be the best ones for viewing our planet’s partner at a convenient time and in its “best light”. Following Saturday’s new moon annular solar eclipse, the moon will spend this week as a waxing crescent shining in the evening sky worldwide. As the moon’s angular separation from the sun increases by about 12° per day, it will increase in illuminated phase and linger about half an hour longer after sunset. At the same time, the terminator, the curved, pole-to-pole boundary that separates the moon’s lit and dark hemispheres, will migrate across the moon and gradually straighten out.

The ever-changing shape of the lunar terminator told the ancients that the moon was a sphere. The terminator is actually a ring that encircles the moon – but from Earth we only see half of it. Every object orbiting a star has a terminator delineating its lit and dark sides. If it’s rotating, an observer standing on the surface of that object will see the star rise (or set) as the terminator sweeps past them. Everyone on Earth is passed by Earth’s own terminator at every sunrise and sunset. On an alien planet that orbits more than one star, there will be multiple terminators and the concept of sunset and sunrise, and day and night, will be more complicated!

All of this is important because the rays of sunlight striking the moon alongside the terminator are nearly horizontal, emphasizing every hump, bump, boulder, hill, ridge, crater rim, and mountain – producing spectacular vistas in binoculars and backyard telescopes. When the moon is waxing between new moon and full, the terminator is sweeping across its Earth-facing hemisphere. Night by night, and even hour by hour, new features become showcased – so check back regularly. As a bonus, waxing moons are ready for viewing as early as 7 pm local time at mid-northern latitudes in October – perfect for junior astronomers and future astronauts! A fun project is to look for craters that are dark one night are filled with light on the next. Partially lit craters that are bisected by the shadow of their rims tell us both the elevation profile of the rim and also whether the crater floor is flat, cone-shaped, or a bowl. (When the moon is waning the sunlight streams in from the west instead, giving us more information.)

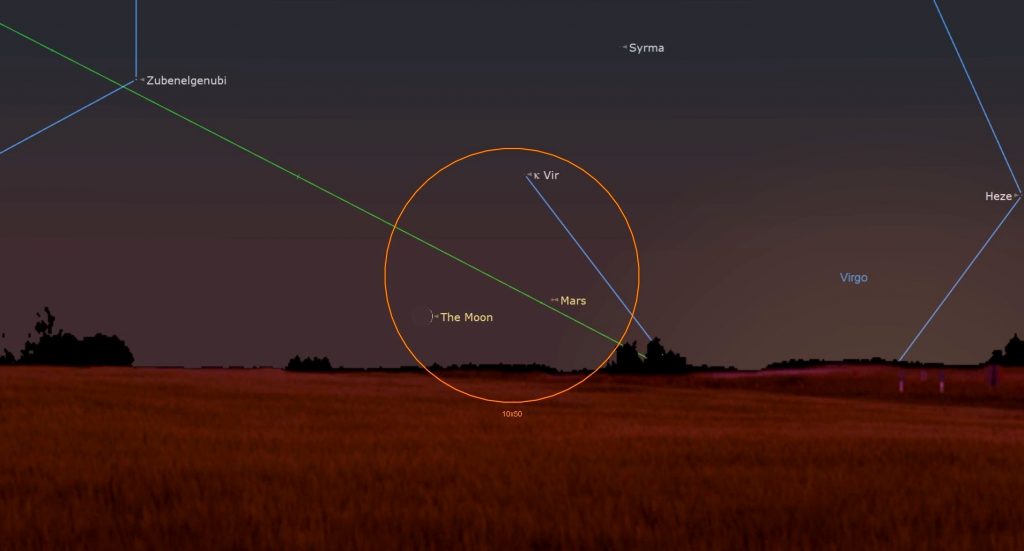

After sunset tonight (Sunday, October 15), the razor-thin crescent of the moon will be positioned just above the western horizon and only two finger widths (or 2 degrees) from Mars. At mid-northern latitudes the duo will be very hard to spot in the twilit sky. From there, Mars will be located to the moon’s right. Observers at tropical latitudes and farther south will see the duo much more easily, with Mars located to the moon’s lower right. Regardless of viewing location, they’ll be cozy enough to share the view in binoculars, but don’t point any optical device in their direction until the sun has completely set.

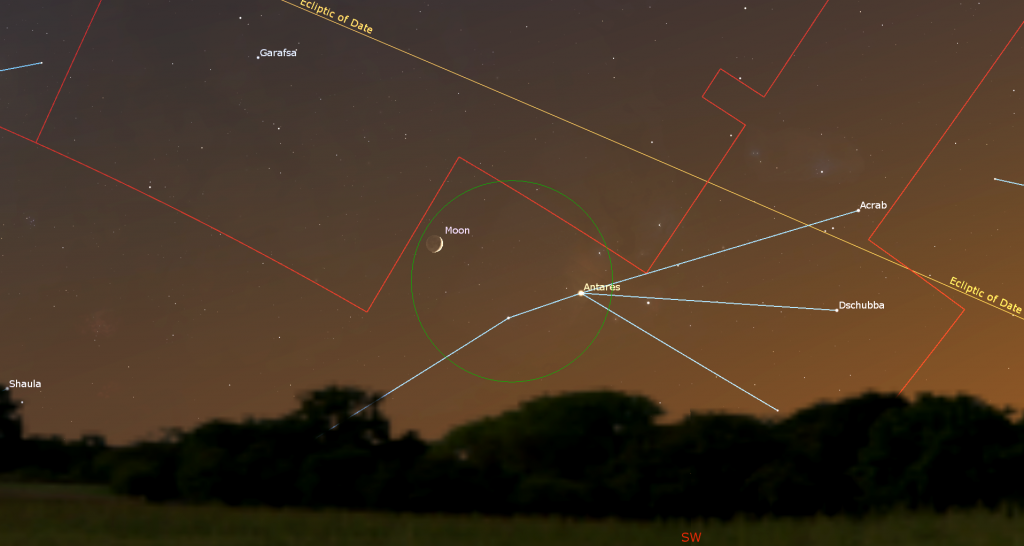

The 5%-illuminated moon will be a bit easier to see in the twilight on Monday, but the stars of Libra (the Scales) that surround it will remain hidden. On Tuesday, the moon will slide into Scorpius (the Scorpion). As the sky darkens, watch for that critter’s brightest star, Antares, twinkling less than a fist’s width to the moon’s upper left (or celestial ESE). The grey oval of Mare Crisium will be nicely framed within the crescent of Tuesday evening’s moon.

The moon-Antares duo will return on Wednesday, with the moon shining to the upper left of the star. Hours earlier, observers in southwestern Asia can watch the moon pass in front of (or occult) Antares. For those in the Azores, eastern Canary Islands, most of Europe (except northern Scandinavia), most of northern Africa, and the rest of the Middle East, the occultation will occur in daytime.

From Thursday onwards the lovely crescent moon will set late enough for the stars to join it. You should be able to find its crescent in the afternoon daytime sky. After dusk, the Teapot-shaped stars of Sagittarius (the Archer) will appear to the moon’s left. On Thursday, the curved trio of large craters Theophilus, Cyrillus, and Catharina will be prominent to the left of the terminator. You can tell what order they were formed in by observing how sharp and fresh Theophilus’ rim appears, and by the way its rim has overprinted neighboring Cyrillus. Depending on what time zone you are viewing from, the floor of Catharina, the most southerly and westerly of the three, will be fully or partially dark. Sweep a little northward and look for the wrinkles snaking across the lit half of Mare Serenitatis.

Mare Serenitatis will fill with light while the moon continues across the Archer’s territory on Friday and Saturday. Our natural satellite will complete the first quarter of its monthly orbit around Earth on Sunday, October 22 at 03:29 Greenwich Mean Time, which translates to Saturday at 11:29 pm EDT or 8:29 pm PDT. On Saturday night, the moon’s 90 degree angle from the sun will make the terminator a straight-line bisecting the moon, and producing a half-moon shape lit on its eastern side. Observers in Europe and Africa can look for the Lunar X on the moon that evening.

The waxing gibbous moon will end this week in Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) and shining off to the right (celestial west) of Saturn next Sunday night.

The Planets

The medium-bright, yellowish dot of Saturn will first appear in the lower part of the southeastern sky after sunset. Then it will remain visible all night long while it crosses the sky. You’ll get the clearest views of Saturn in a telescope while it is higher, between 7 pm and 1 am local time. Once it’s dark, watch for the faint stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) sparkling to the left and right of Saturn, respectively. The bright trio of the Summer Triangle asterism stars will shine high above it, and the Great Square of Pegasus stars will be positioned a few fist diameters to the planet’s upper left. If you have an unobstructed southern view, look for the very bright star Fomalhaut or Alpha Piscis Austrini (the Southern Fish) shining two fist diameters below Saturn.

Any size of telescope will show Saturn’s beautiful rings. If your optics are of good quality and the air is steady, try to see the Cassini Division, a narrow gap curving between the outer and inner rings. You can also look for a small wedge of dark shadow cast upon on the rings at the eastern limb of the planet’s globe and faint belts of dark cloud that encircle Saturn. Remember to take long, lingering looks through the eyepiece – so that you can catch moments of perfect atmospheric clarity. Good binoculars can hint at the shape of Saturn’s rings, too.

From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves above, below, and alongside the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from lower left of Saturn (celestial east) tonight to the upper right of the planet (celestial west) next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks. You may be surprised at how many of them you can see through your telescope if you look closely.

This summer, the ice giant planet Neptune, currently about 790 times fainter than Saturn, will be lurking 2.4 fist diameters to Saturn’s lower left, or 24° to its celestial northeast. Magnitude 7.8 Neptune is visible in backyard telescopes, especially between 8 pm and 3 am local time, when the blue planet is highest. Good binoculars can show Neptune, too – if your sky is very dark. Make your attempt earlier this week. Its blue, star-like disk size is currently a tiny 2.36 arc-seconds across.

This week, Neptune’s westerly retrograde motion will carry it closely past a small, warm-white star that shines at the same brightness as Neptune’s blue dot. In binoculars the star will shine below Neptune, but most telescopes will flip and/or mirror the view. They’ll be closest at mid-week. See if you can notice that the star twinkles, while Neptune doesn’t (much). A much brighter star named 20 Piscium will shine off to their left (or celestial northeast), helping you find them in binoculars.

Extremely bright Jupiter, which will reach peak visibility when opposite the sun in early November, will be rising in the east around 7:15 pm local time this week. Its best telescope viewing time will commence around 9:15 pm. The two brightest stars of Aries (the Ram), named Hamal and Sheratan, will be shining a generous fist’s diameter above the giant planet this year. The winter constellation of Taurus (the Bull) will follow Jupiter across the sky during the night, and then the bright planet will catch your eye when it gleams in the western sky around breakfast time.

Binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons in a line beside the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another.

Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in mid-evening Eastern Time on Sunday, Tuesday, Friday, and next Sunday night. It’ll show after midnight on Tuesday, Friday, and next Sunday morning, and before dawn on Monday and Saturday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Tuesday morning, October 17, Europa’s small shadow will cross Jupiter from 2:50 to 5:05 am EDT (or 06:50 to 09:05 GMT). Early on Friday morning, October 20 observers with telescopes in the Americas can watch the round black shadows of two of Jupiter’s moons cross the giant planet together for more than 90 minutes. Io’s small shadow will begin its trip across Jupiter’s equator at 1:41 am EDT or 05:41 GMT. Ganymede’s much larger shadow will appear in Jupiter’s southern polar region at 2 am EDT or 06:00 GMT. They’ll cross together until Ganymede’s shadow moves off the planet at 3:40 am EDT or 07:40 GMT, leaving Io’s shadow to complete its crossing about 10 minutes later. On Saturday evening, October 21, Io’s small shadow will cross Jupiter’s equatorial region from 8:10 to 10:15 pm EDT (or 00:10 to 02:15 GMT on October 22). (These times may vary by a few minutes and other time zones of the world will have their own crossings.)

The planet Uranus is following Jupiter across the sky this year. Magnitude 5.6 Uranus is visible in both binoculars and small telescopes when a bright moon isn’t nearby. Uranus is located a slim fist’s diameter to Jupiter’s lower left (or 9.3° to the celestial east), just on the Aries side of its border with Taurus. The bright little Pleiades star cluster will be located a similar distance to Uranus’ left. This year, a pair of medium-bright stars named Botein and Al Butain IV (or Sigma and Zeta Arietis) will shine two finger widths above Uranus. Since they are easy to see in binoculars, they can act as your guides. Uranus’ small coloured disk is a treat to see in a telescope. The best times for looking start around 9:45 pm local time.

Venus and Jupiter will continue to gleam on opposite sides of the pre-dawn sky this week. If you head outside on a clear morning around 6:30 am local time, Venus and Jupiter will be positioned at about the same height in the sky, though Jupiter will be descending in the west while Venus climbs in the east. The bright stars of the winter constellations will shine between them in the southern sky. Venus will dominate the eastern pre-dawn sky until January. It will be climbing a little farther from the morning sun with each passing day until next Monday. Viewed in a telescope this week, our hot sister-planet’s disk will be shrinking in size and nearly half-lit. Venus will rise among the stars of Leo (the Lion) at about 3:30 am local time.

Some Double Stars You Can See in Binoculars

Bright moonlight hides the fainter celestial objects, but stars are moonlight tolerant, especially when using binoculars and backyard telescopes. To make hay while the moon shines, check out double stars, two or more stars that are either orbiting close to one another (binary stars), or those which appear to sit near one another but are actually at vastly different distances from us (line of sight double stars). The stars can look the same, like distant car headlights, or shine with different brightnesses and contrasting colour. Here are a few suggestions to seek out in early October, moonlit or not.

The very bright star Deneb in Cygnus (the Swan) shines overhead on early-October evenings. When facing south in mid-evening, the sky just above (to the celestial northwest of) Deneb contains several double stars that can be split easily in binoculars. Warm-coloured Omicron1 and Omicron2 Cygni, both of which shine at about magnitude 3.9, are easily visible without binoculars. Also designated as o1,2 Cyg, they are separated by a generous finger’s width (or 1°). The lower (more southerly) star o1 is accompanied by a fainter white star named 30695 Cygni shining just to its upper right (or northwest). Another fainter star shines even closer in below it (to the south).

Located several finger widths to the upper right (or 3 degrees to the northeast) of Omicron, but still within the same binoculars field of view, look for blue-white star Ruchba (or Omega1 Cygni) shining a small distance below (or 19 arc-minutes to the south) a cosy pair consisting of reddish Omega2 Cygni huddling with a white star named HIP 101206. (The prefix HIP comes from the Hipparchus star catalog.) A third, white, magnitude 5.7 star named 43 Cygni sparkles alone just to their upper right (or 40 arc-minutes to their west).

The star Albireo, aka Beta1,2 Cygni or β1,2 Cyg is a gorgeous coloured double. It marks the head of the swan below and between Deneb and even brighter Vega. Binoculars will reveal close-together sapphire and topaz gems. The hotter, blue star β2 shines less brightly than yellow β1. Both stars are around 370 light-years away from us, but we don’t yet know if they are a binary pair or a line-of-sight pair. The name Albireo arose before the invention of telescopes revealed to us that it is two stars. Pre-Islamic Arab astronomers called it minqār al-dajājah, “ the hen’s beak”.

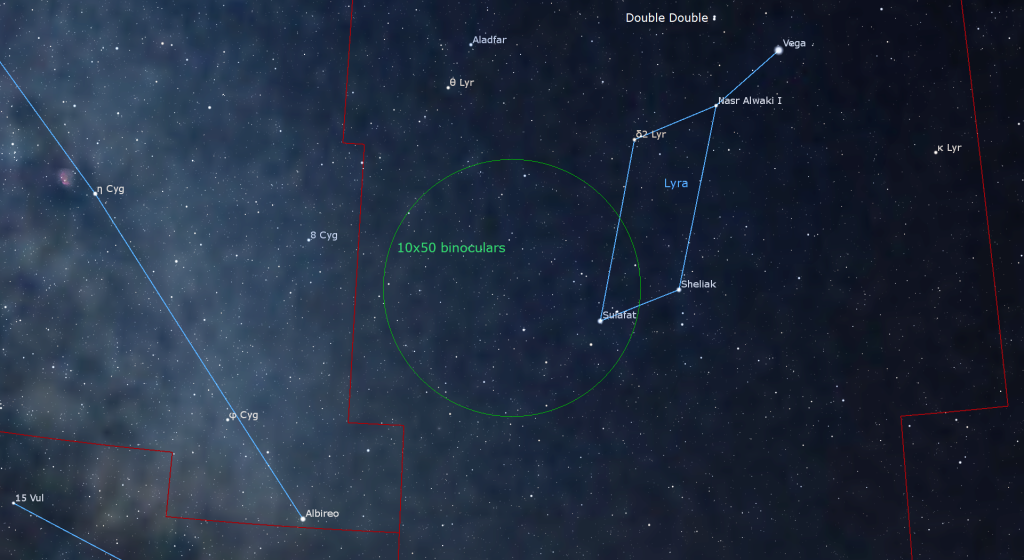

Speaking of Vega aka Alpha Lyrae, the little star shining a finger’s width to the upper left (northeast) of Vega is Epsilon Lyrae. Sharp eyes and binoculars will split it into a matching pair of white stars. A telescope at high power will show that each of them is a close-together pair that we have nicknamed the Double Double! All four stars appear to gravitationally bound together, with each duo orbiting one another with a period of about 1,200 years, and the two pairs circling one another over hundreds of thousands of years!

Each corner of Lyra’s parallelogram is marked by a multiple star. Nasr Alwaki I or Zeta Lyrae (ζ1,2 Lyr), the corner closest to bright Vega, can be split with binoculars. Both components are white – one star slightly brighter than the other. Each of these stars also has a partner that is too close together to split visually. Moving clockwise, at the lower right (southwest) corner star is Sheliak, the brightest of a tight little grouping of stars visible in a telescope. Sheliak itself has a close-in, dim companion in an eclipsing binary system with a 13-day period. The hot, blue giant star Sulafat sits at the farthest corner from Vega. 620 light-years-distant Sulafat is much larger than Vega – an old star on its way to becoming an orange giant many years from now. Add the slightly dimmer stars Lambda Lyrae and HD 176051 to its south and west, respectively to form a naked-eye triple star. Delta Lyrae (δ Lyr) marks the upper left (northeast) corner of the parallelogram. Sharp eyes and binoculars will easily split the double into one blue and one red star. The blue star is one hundred light-years farther away than the red one; they just happen to appear close together along the same line of sight.

Morning Zodiacal Light

During autumn at mid-northern latitudes every year, the ecliptic extends nearly vertically upward from the eastern horizon before dawn. That geometry favors the appearance of the faint zodiacal light in the eastern sky for about half an hour before dawn on moonless mornings. Zodiacal light is sunlight scattered by interplanetary particles that are concentrated in the plane of the solar system – the same material that produces meteor showers. It is more readily seen in areas free of urban light pollution.

Between now and the full moon on October 28, try looking for the phenomenon as a broad wedge of faint light extending upwards from the eastern horizon and centered on the ecliptic. It will be strongest in the lower third of the sky, below the bright planet Venus. Try taking a long exposure photograph to capture the zodiacal light, but don’t confuse it with the Milky Way, which will be extending upwards nearby in the southern sky.

Pegasus and The Celestial Coordinate System

If you missed last week’s information about the constellation Pegasus (the Winged Horse) and its connection to the celestial coordinate system, I’ll posted it here.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

Taking advantage of the crescent moon in the sky this week, the RASC Toronto Centre astronomers will hold their monthly City Sky Star Party in Bayview Village Park (a short walk from the Bayview TTC subway station), starting after dusk on the first clear weeknight this week (Mon, Tue or Thu only). Check here for details, and check the banner on their website home page or Facebook page for the GO or NO-GO decision around 5 pm each day.

At 7:30 pm on Wednesday, October 18, the RASC Toronto Centre will livestream their free monthly Speaker’s Night Meeting. The speaker will be Professor Margaret Campbell-Brown, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Western Ontario. Her topic will be When worlds collide: asteroids, comets and the Earth. Check here for details and watch the presentation at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live.

Eastern GTA sky watchers are invited to join the RASC Toronto Centre and Durham Skies for solar observing and stargazing at the edge of Lake Ontario in Millennium Square in Pickering on Friday evening, October 20, starting at 6 pm. Details are here. Before heading out, check the RASCTC home page for a Go/No-Go call – in case it’s too cloudy to observe.

On Friday, October 20 from 7:30 pm to 9:30 pm, RASC Toronto Centre will host Family Night at the David Dunlap Observatory for visitors aged 7 and up. You will tour the sky, visit the giant 74” telescope, and view celestial sights through telescopes if the sky is clear. This program runs rain or shine. Details are here, and the link for tickets is here.

Spend an afternoon in the other dome at the David Dunlap Observatory! On Saturday afternoon, October 21, visitors 6 years old and up can join me in my Starlab Digital Planetarium for an interactive journey through the Universe at DDO. We’ll tour the night sky and see close-up views of galaxies, nebulas, and star clusters, view our Solar System’s planets and alien exo-planets, land on the moon, Mars – or the Sun, travel home to Earth from the edge of the Universe, hear indigenous starlore, and watch immersive fulldome movies! Ask me your burning questions, and see the answers in a planetarium setting – or sit back and soak it all in. Please note that all guests will sit on a clean floor. A registered adult must accompany all registered participants under the age of 16. We run one session at 1 pm and another one at 2:45 pm. More information and the registration links are here.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!