Six Evening Planets for Solstice Season, Meagre Meteors, the Early Waning Moon Stomps Stars, and Appreciating the Pleiades!

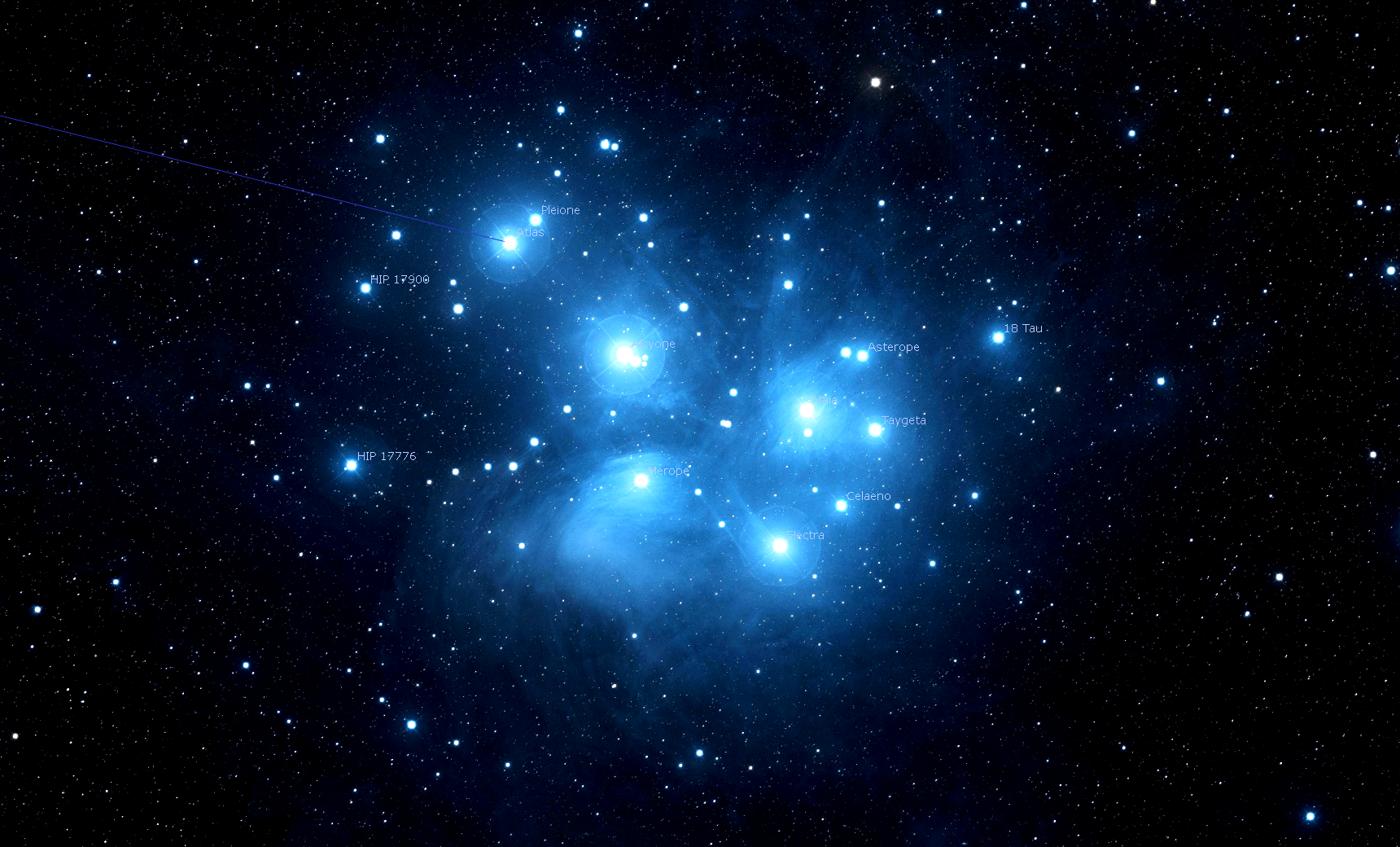

This image of the Pleiades star cluster from Stellarium shows the “sisters” shrouded by blue nebulosity – their stars’ light scattering from foreground dust. Their parent stars Atlas and Pleione are huddled at top left. The image spans about 2 finger widths of the sky, or 2 degrees.

Happy Solstice, Winter Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of December 19th, 2021 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. I repost these emails with photos at http://astrogeo.ca/skylights/ where the old editions are archived. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

Venus and Jupiter will shepherd Saturn in the west after sunset this week, with Mercury joining their conga line at dusk and the ice giants following them west in late evening. Meanwhile the December solstice means the shortest daylight and an early rising waning moon to peruse. That moon will occult two stars this week. Comet Leonard fades, the Ursids meteors appear, and we appreciate the Pleiades cluster. Read on for your Skylights!

‘Tis the Seasonal Change

Happy Holidays, everyone! Or, as we astronomers say, “Have a Happy Solstice and a Merry Perihelion!”

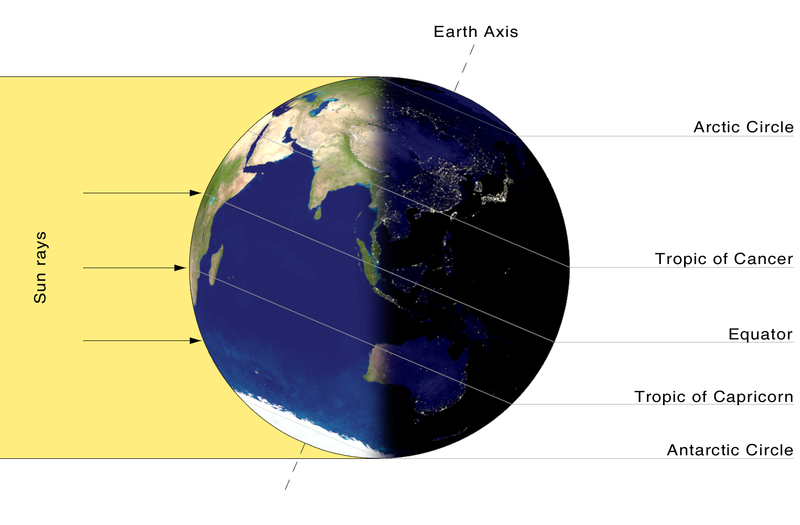

The December solstice, or winter solstice, will officially occur on Tuesday, December 21 at 15:59 GMT (or 10:59 am EST and 7:59 am PST). At that time, the north pole of Earth’s axis of rotation will be leaning in a direction opposite from the sun. The event marks the beginning of winter for the Northern Hemisphere – but not winter weather, as I’ll discuss below. On the day of the winter solstice, the sun’s highest point in the daytime sky, which always occurs at local noon, is lower than on any other day of the year because the sun is farthest south of the Celestial Equator. (An object’s highest position in the sky is called its culmination.)

At the December solstice, the points on the horizon where the sun rises and sets are shifted well south of east and west, so the arc that the sun traces out across the daytime sky is shorter than on any other day of the year – and it therefore needs much less time to make that crossing. With noon still pinned at mid-day, it’s the sunrise and sunset times that are later and earlier, respectively – so Northern Hemisphere dwellers receive the shortest duration of daylight and the longest nights for the year.

The arc of the sun’s path continues to shorten if you move farther north on Earth – until you reach the Arctic Circle at 66°33′48.4″ North latitude. Anywhere along that ring around the Earth, the sun won’t rise at all on the solstice – but you would still see a twilit sky during the noon hour. For residents living above about latitude 80° N, it’s dark 24 hours a day, until spring. That is great for astronomy – if you can stand the cold!

The sunlight that northerners get this at time of year is weaker in intensity because it’s spread over a larger area – for the reason that a flashlight beam looks dimmer when you shine it obliquely at a wall (try it!). On the December solstice, the sun will be directly overhead at noon if you live at 23° 26’ 11.2” S, otherwise known as the Tropic of Capricorn. The sunlight’s intensity weakens more and more as you travel farther from that latitude. (The Tropic of Cancer works the same way for the Southern Hemisphere on the June solstice.)

Fewer daylight hours and weaker sunlight results in less received solar energy (insolation) and therefore colder temperatures! It is not the case, as some people think, that days are colder in winter because we are farther from the sun (a position called aphelion). That event happens every year in early July. On the contrary – Earth’s minimum distance from the sun (perihelion) occurs every January 4, give or take a day.

After Tuesday, our daylight hours will slowly start to increase again. For our friends in the Southern Hemisphere, the sun will attain its highest noon-time culmination for the year on the December solstice, and kick off their summer season. Their winter will commence six months from now, at the June solstice.

Some scholars think that Christmas was deliberately scheduled close to the winter solstice, and Easter close to the vernal equinox, because the early non-Christian “pagans” were already holding celebrations at that time to mark the astronomical changing of the seasons.

Ursids Meteor Shower Peak

The annual Ursids meteor shower, produced by debris dropped by periodic comet 8P/Tuttle, runs from December 17 to 23. The shower will peak during the early hours of Tuesday, December 22, when seeing between 5 and 10 meteors per hour is possible under dark skies. The best time to watch will be the hours before dawn. Unfortunately, a waning gibbous moon will shine in the post-midnight sky, spoiling the show for this year. True Ursids will appear to radiate from a position in the sky above the Little Dipper (Ursa Minor) near Polaris, but the meteors can appear anywhere in the sky.

Last December on Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy, we covered meteors and meteorites. It’s on YouTube here.

Comet Leonard Going Forward

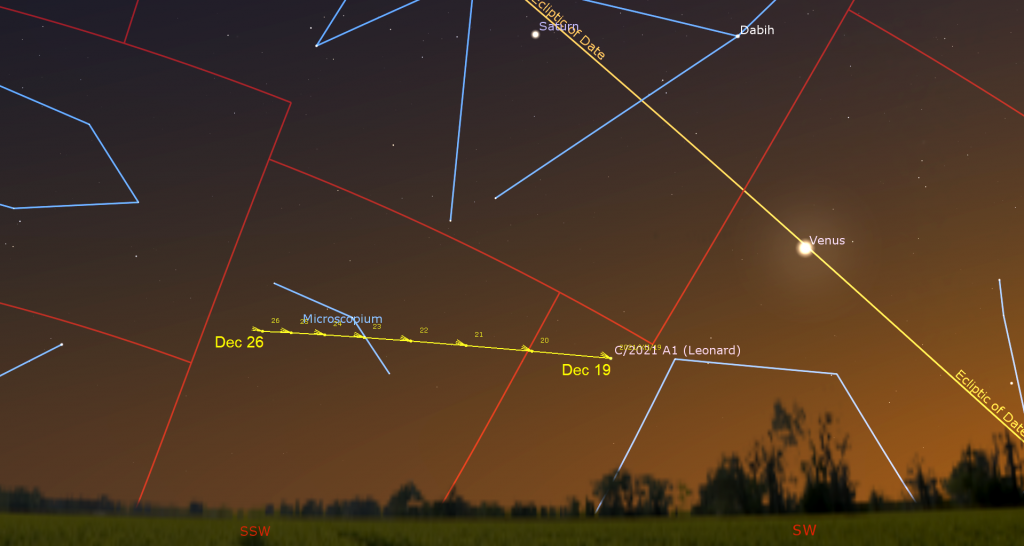

Comet C/2021 A1 (Leonard) is fading now. For observers at mid-northern latitudes around the globe this week, the comet will progress right to left (or celestial southeastward) above the western horizon after sunset – to the lower left (or celestial southwest of) Venus. To see the comet, you’ll need binoculars and a cloud-free, haze-free southwestern horizon. The best viewing time will be just after 5:30 pm in your local time zone. (Don’t aim binoculars west until the sun has fully disappeared.)

For viewers in the tropics and the Southern Hemisphere, the comet will be well positioned to the upper left of Venus, in a dark sky – but every night it will be receding from Earth and diminishing in brightness and apparent size. That trend will continue after it passes the sun on January 3.

The Moon

For most of the year, once the moon passes its full moon phase, it rises late enough that the evening sky is moonless during the ensuing week. But during December, the sun sets so early in the Northern Hemisphere – before 4:45 pm local time at the latitude of Toronto this week – the waning gibbous moon rises much earlier. Tonight (Sunday), for example, the moon will rise at 5:15 pm and shine all night long. It will then rise about an hour later each night. Next Sunday the moon will have reached its third quarter phase when it rises shortly after midnight.

I’m used to seeing the honey-coloured, third quarter moon, illuminated from the east instead of the west, rising while I’m driving home from a dark observing site in the wee hours. (We usually pack up our telescopes once moonlight starts to contaminate the inky black, star-studded sky.) Since the moon will be rising at a reasonable hour of the evening this week, even early-to-bed stargazers can see the moon sporting its waning phases – if you don’t mind bundling up a little. So grab your binoculars and dust off the telescope to see the moon’s familiar features lit from the opposite direction!

Due to its orbit’s 5° inclination and ellipticity, the moon tilts up-and-down and sways left-to-right by a small amount while keeping the same hemisphere pointed towards Earth at all times. Over the course of many months, this lunar libration effect lets us see 59% of the moon’s total surface – without leaving the Earth! Libration can be detected by noting the way major features, such as the dark and very round Mare Crisium (the Sea of Crises), moves toward and away from the limb of the moon, and up and down. The 556 km-wide basin is easy to see using your unaided eyes, binoculars, and telescopes. It always sits in the northeastern quadrant of the moon – that’s the upper right for Northern Hemisphere observers (lunar east is the opposite of sky east). Keep an eye on Mare Crisium over the next few months and note how it shifts towards and away from the moon’s edge while it also rides higher and lower.

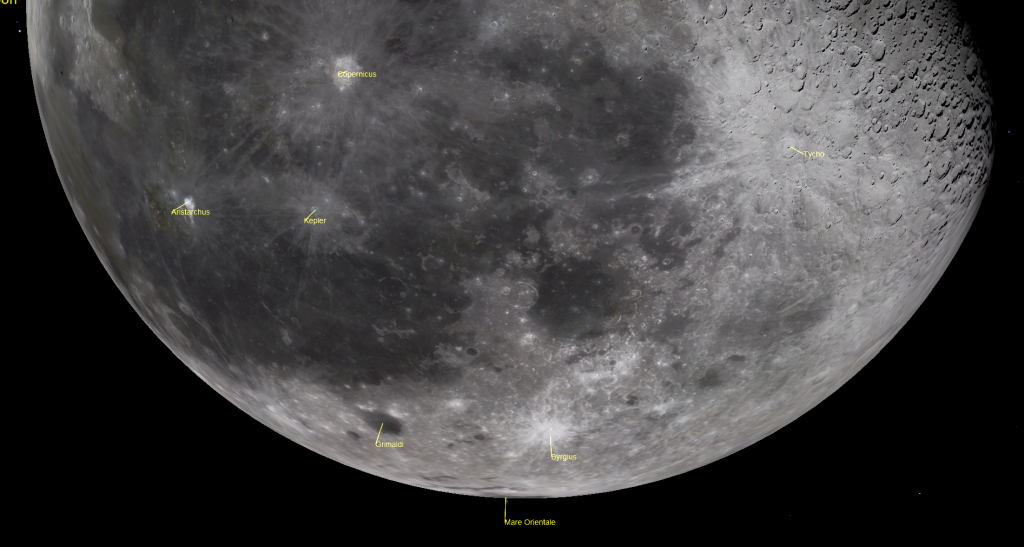

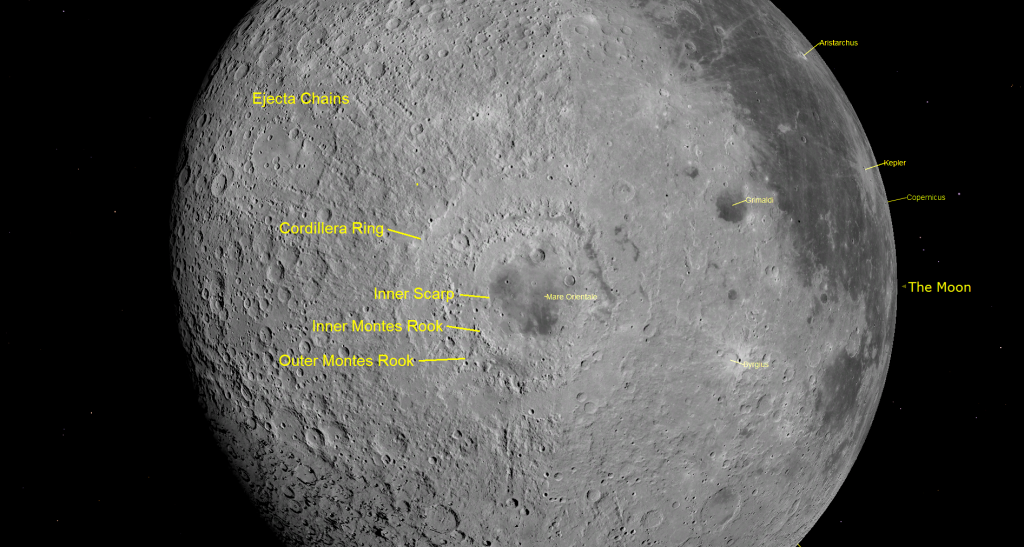

Towards the end of this week, the moon’s libration will allow us to see features along its southwestern limb that are normally not visible, particularly the edge of Mare Orientale (the Eastern Sea). Formed 3.84 billion years ago, Mare Orientale is the youngest and most pristine of the lunar basins. It was discovered in 1961, well before the Apollo Missions, by Bill Hartmann who was working on the Rectified Lunar Atlas project. He projected Earth-based photographs of the moon onto a plain, white, 3-foot hemisphere, and then re-photographed features from directly above them. The eastern rings of Mare Orientale were revealed.

The mare was formed when an asteroid-sized object about 65 km in diameter and travelling at 15 km/s (or 54,000 kph) slammed into the moon. Most lunar basins were flooded by later dark lava flows, creating the “man in the moon” and “lady of the moon” patterns we see from Earth. But Mare Orientale is pristine, with very little basalt infill. It has, at most, a 1 km deep lozenge of pooled lava in its centre. It is encircled by three distinct rings. The Cordillera Mountains ring is 930 km in diameter. The Outer Rook Mountains (620 km) and the Inner Rook Mountains (480 km) are inside it. Around the three rings is a 500 km-wide zone of ejecta hosting radiating “scratches” and chains of secondary impacts. The mare will appear as an elongated dark zone along the moon’s edge.

Let’s look at what else the moon will get up to this week. Since the moon was full on Saturday night, Sunday night’s moon will be almost as bright when it rises among the stars of Gemini (the Twins). The waning moon will spend Tuesday night in Gemini and then cross into Cancer (the Crab) for Wednesday.

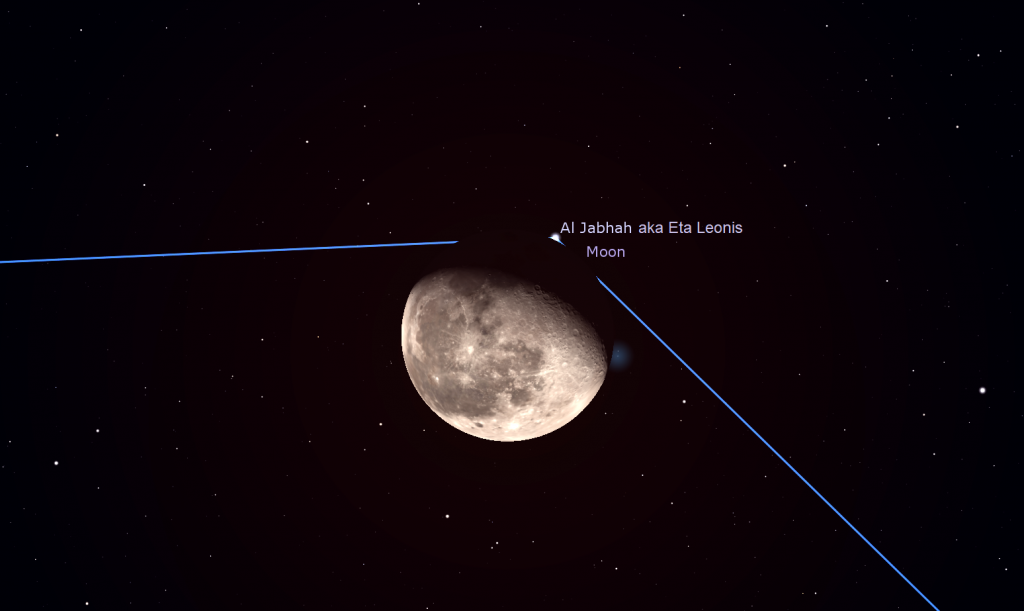

Observers in Canada and the Continental USA on Thursday, December 23, will be able to watch the 78%-illuminated moon pass in front of (or occult) the bright medium-star Eta Leonis, also known as Al Jabhah, which marks the chest of Leo (the Lion). At 9:51 pm EST (or 02:51 Greenwich Mean Time on Friday), the bright leading edge of the moon will pass in front of the star. In the Eastern Time Zone, the moon will have just risen in the eastern sky – so you’ll need an unobstructed horizon to see it. An hour later, at 10:52 pm EST, the star will pop into sight from behind the moon’s trailing, dark hemisphere. Any size of telescope will allow you to see the event. Start watching a few minutes before the times I mentioned. Timings vary a little by location.

The moon will spend Friday night in Leo, too. On the coming weekend, the half-illuminated moon will shine in Virgo (the Maiden). On Saturday night, December 25, observers in parts of North America can see the moon occult another star named v Virginis between 11:12 pm and 12:06 am EST (or 04:12 and 05:06 GMT on December 26). On Saturday and Sunday, the late rising moon will be lingering into the morning daytime sky.

The Planets

Extremely bright Venus will continue to shine in the southwestern sky after dusk this week – but it’s exiting the stage now after many months. The magnitude -4.79 planet will become visible as the sky darkens and then set shortly after 6:30 pm local time. You might need to walk around to find the planet between the trees or buildings after sunset. Viewed in a telescope, Venus will show a very thin, waning crescent on its sun-facing side. Wait for the sun to completely disappear and then aim your telescope at Venus as soon as you can spot the planet in the sky. That way, the planet will be higher and shining through less distorting atmosphere – giving you a clearer view of it. A brighter sky will also allow Venus’ shape to be seen more readily. The planet will grow in apparent disk size and wane in phase every week for the rest of this year because Venus will be traveling into the space between Earth and the sun.

Mercury will become observable in the western post-sunset sky this week – better each evening as it flees the sun. You’ll need a cloud-free, unobstructed southwestern horizon to catch it. To make things easier, next Sunday, December 26, Venus will sit only a palm’s width below much brighter Venus.

Jupiter is the bright, white planet shining three fist diameters to Venus’ upper left (or 31° to the celestial east). Much fainter and creamy-coloured Saturn will appear midway between them. All three planets are being carried relentlessly sunward by Earth’s orbital motion. Once Jupiter becomes unobservable beside the sun in late January, we’ll have to wait until August to see a bright evening planet (Saturn)! Jupiter and Mars won’t return until autumn.

At this time, Saturn is parked in Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). Jupiter has moved eastward into next-door Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). Saturn will set in the west at about 8 pm local time, with Jupiter 90 minutes behind that – so observe each planet as early as you can spot it, while it’s higher. Remember to take long, lingering looks through the eyepiece – so that you can catch moments of perfect atmospheric clarity.

From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves all around the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the lower right (celestial west) of Saturn tonight to the upper left (celestial east) of Saturn next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope?

Binoculars and small telescopes will show you the Jupiter’s four large Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Since Jupiter’s axial tilt is a miniscule 3°, those moons always look like beads strung on a line that passes through the planet, and parallel to Jupiter’s dark equatorial belts. That line of moons, and the belts, tilt as Jupiter crosses the sky. The moons’ arrangement varies from night to night. Io, for example, orbits Jupiter once every 42 hours. From one night to the next night, 24 hours has elapsed on Earth – time for Io to complete half an orbit and shift from one side of Jupiter to the other. The other Galilean moons move less rapidly, taking between 3.5 and 16.7 days to orbit Jupiter.

For observers in the Eastern Time Zone with good telescopes, the Great Red Spot (or GRS) will be visible while it crosses Jupiter after dusk on Monday and Saturday, in mid-evening on Wednesday, and after 8 pm tonight (Sunday), Wednesday, and Friday.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Tuesday evening, December 19, observers in the Americas with telescopes can watch the small round shadow of Jupiter’s moon Io cross the planet from 6:35 pm EST (or 23:35 GMT). Jupiter will be setting in the Eastern Time Zone before they complete their crossing, but observers farther west can watch them longer.

Distant, dim Neptune is in the evening sky, too – near the border between Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and western Pisces (the Fishes). The magnitude 7.9 planet is also 2.2 fist diameters to the upper left (or 22° to the celestial east) of Jupiter. Neptune continues the string of planets that starts at Venus – defining the plane of our solar system across the sky.

Extending the line over to the southeastern sky, Uranus is shining at magnitude 5.7. Look for the planet’s small, blue-green dot moving slowly retrograde westwards in southern Aries (the Ram), a fist’s width below (or 11.5 degrees southeast of) that constellation’s brightest stars, Hamal and Sheratan. Or use binoculars to locate Uranus using the nearby star Mu Ceti. Uranus is also about 1.6 fist diameters to the upper right (or 16 degrees to the celestial west-southwest) of the Pleiades star cluster. This week Uranus will be observable all night long – especially around 9 pm local time, when it will have climbed more than halfway up the southeastern sky. Two fists farther east you’ll find the dwarf planet Ceres.

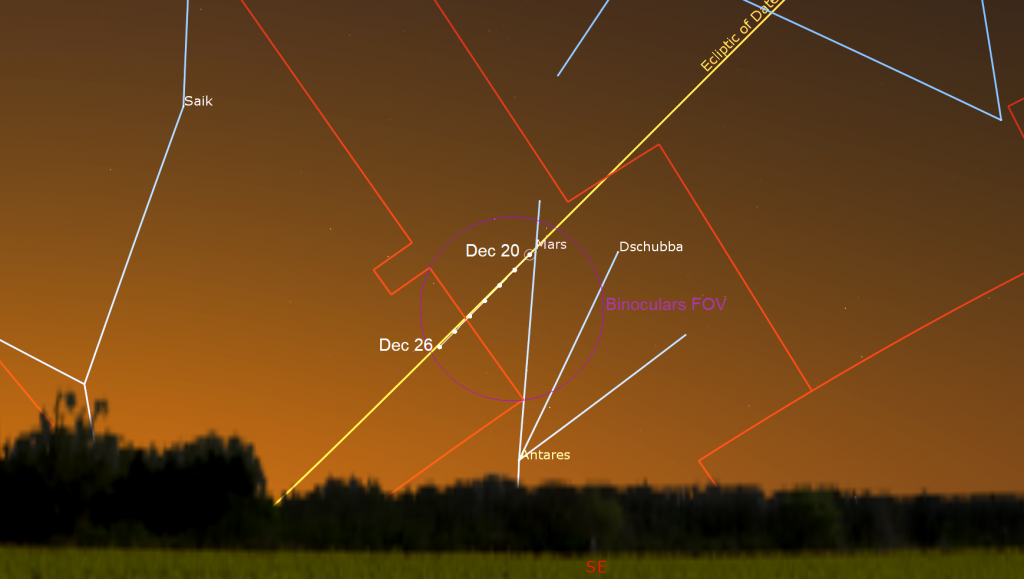

This week Mars will continue its year-long journey to a bright showing at opposition in December, 2022. You might spot the magnitude 1.6 planet shining very low in the southeastern sky just after it rises at around 6 am local time, especially if you live at a tropical latitude. Your odds of successfully spotting Mars will improve on each subsequent morning. Take care to turn binoculars and telescopes away from the eastern horizon well before the sun rises.

Low in the southeastern pre-dawn sky on the mornings surrounding Sunday, December 26, the motion of the red planet Mars will carry it past its “rival”, the bright star Antares in Scorpius. At its closest approach on December 27, Mars will shine several finger widths to the upper right (or 4.5 degrees to the celestial north) of the star, but they’ll be binoculars-close from December 23 to 31, with Antares shifting higher each morning. Antares will appear slightly brighter than the planet, but it will exhibit a similar reddish color – hence their rivalry! The optimal viewing time at mid-northern latitudes will be around 7 am local time. Observers at southerly latitudes will see the duo shining higher, in a darker sky.

A Christmas Star?

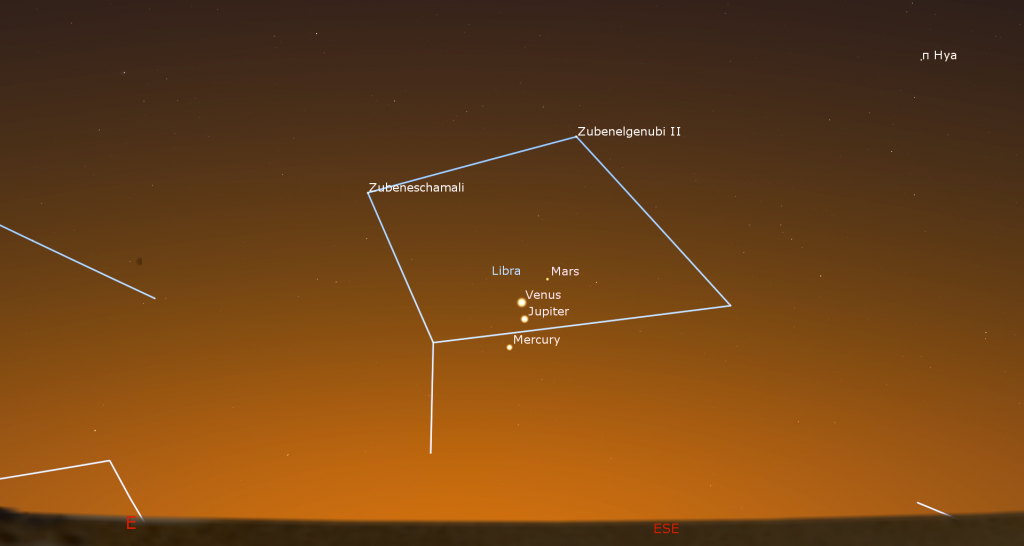

Seeing Venus every evening nowadays, it’s easy to imagine that sky-watchers of old could be captivated by Venus’ brilliance and name it a “Christmas Star”. But Venus puts on these celestial showings every two or three years – hardly a rare occurrence. The event that may have spawned the biblical story of wise men following a star in the east, was a planetary conjunction of Venus, Jupiter, Mars, and Venus that occurred in the pre-dawn sky in early November of the year 1 CE. In fact, on one of those mornings, Venus and Jupiter were so close together that they might have looked like a single, extra-bright object!

All four bright planets were grouped into a stubby line that spanned less than four fingers widths in length. Head outside on the next clear night, hold up your hand beside Venus, and imagine how impressive those other planets gathered around her would have looked.

Appreciating the Pleiades

The beautiful open star cluster known as The Pleiades, the Seven Sisters sits about one and a half fist widths above (or 13° to the celestial northwest of) Taurus the bull’s face. The cluster is one of my favorite wintertime objects. It’s also designated Messier 45 (or M45), part of Charles Messier’s famous list of comet-like objects. Look for it climbing the eastern sky after dusk during December. It moves to high in the southern sky in late evening.

The Pleiades is made up of the young, hot blue stars named Asterope (“A-STER-oh-pee”), Merope, Electra, Maia, Taygeta, Celaeno, and Alcyone. And those stars are indeed related – born of the same primordial gas cloud. In Greek mythology, they were the daughters of Atlas, and half-sisters of the Hyades. Only six of the sister stars are usually seen with unaided eyes – their parents, the stars Atlas and Pleione, are huddled together at the lower (east) end of the grouping.

Galileo was among the first to observe the cluster in a telescope. In 1610, he published a sketch made at the eyepiece. The Pleiades cluster is located about 450 light years away from the sun, and it makes a wonderful target in binoculars or a telescope at low magnification, where many more siblings are revealed! A large telescope under dark skies will also reveal blue nebulosity around the stars – reflected light from unrelated gas and dust that the stars are passing through. This proper motion will eventually carry the cluster to a position below Orion’s feet!

Not surprisingly, many cultures, including Aztec, Maori, Sioux, Hindu, and more, have developed stories around this object. Many indigenous groups view the Pleiades as the doorway in to the afterlife, or the portal through which humans first fell to Earth – naming it the Hole in the Sky. In Japan, it is called Subaru, and forms the logo of the eponymous car maker. Due to its similar shape and diminutive size, some people mistake the Pleiades for the Little Dipper.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory YouTube channel.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds and Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, January 18 at 3:30 pm EST. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!