Smoky Skies, Noctilucent Clouds, the Morning Moon Passes Planets, Venus Kisses the Bees, and Eyeing Ophiuchus!

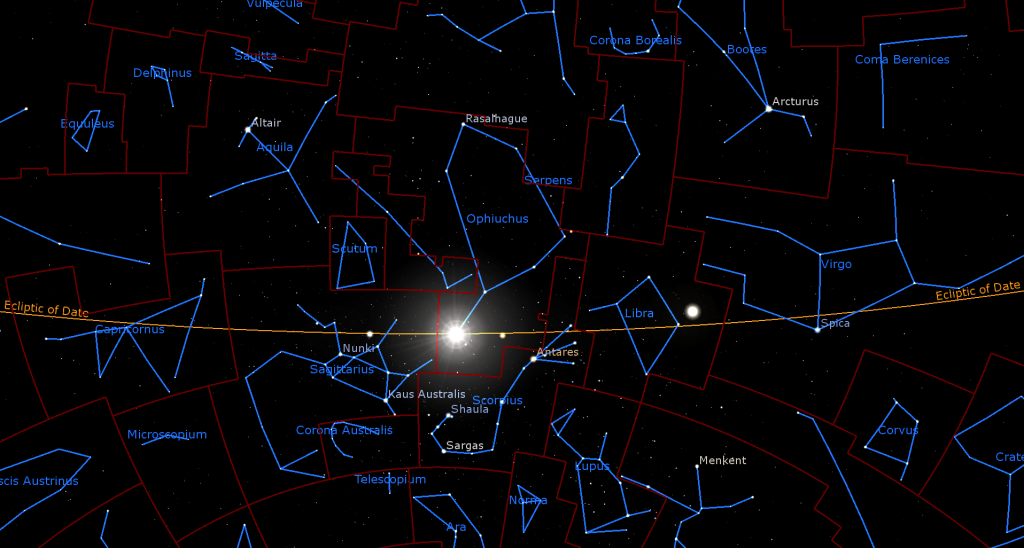

This terrific image by Amir H. Abolfath was featured in NASA’s Astronomy Picture of the Day (APOD) for October 14, 2020. The bright star inside the orange zone at lower left is Antares in Scorpius. The big and bright globular cluster Messier 4 sits to its lower right. The pink region is glowing hydrogen gas surrounding the star Alniyat (or Sigma Scorpii). The bright blue zone at the upper right is light scattered off dust in the triple star system of Rho Ophiuchi within it. Note the deep black shapes produced by opaque interstellar dust, and several more, smaller globular clusters. The area of sky in this image covers a palm’s width top to bottom.

Hello, mid-June Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of June 11th, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The waning moon will spend this week passing the five planets gathered in the eastern pre-dawn sky, leaving nights skies worldwide moonless and ready for telescopes and binoculars. Unfortunately, wildfires are wreaking havoc with lives and observers in many places. If your skies are clear after dusk, check out Venus near the Beehive cluster, Mars, look for noctilucent clouds, and later, enjoy the sights of Ophiuchus. Read on for your Skylights!

Smoky Skies

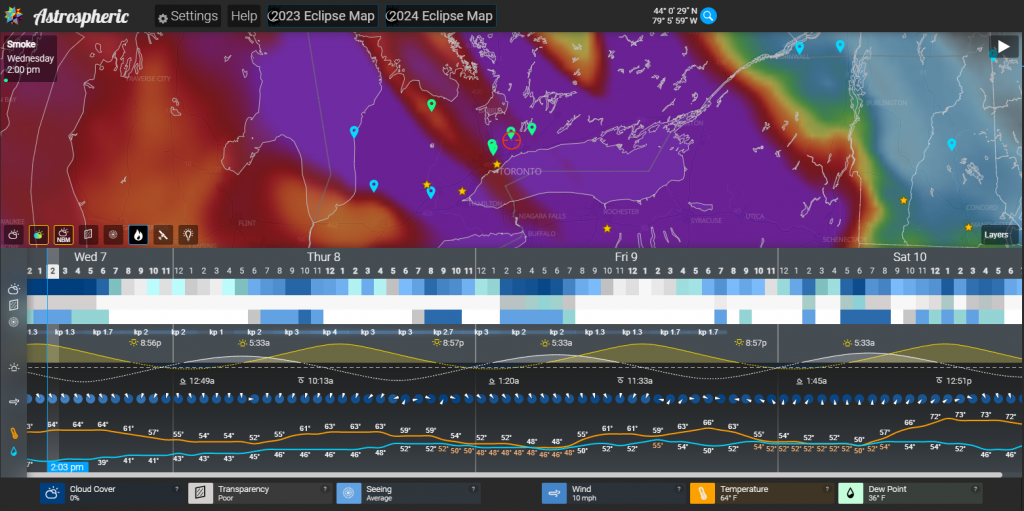

Wildfires are raging across North America. The prevailing northwesterly winds have been carrying heavy smoke across my location in southern Ontario. The question is – if the days are sunny and the nights cloud-free, can we observe despite the smoke?

Airborne particulate matter (PM) includes aerosols and both natural and industrial organic and metallic compounds. Particles with diameters of 10 micrometres or smaller arising from construction, energy production and waste combustion, wind-blown dust and pollen, and wildfires can all be of concern in high concentrations. Those are referred to as PM10. For human health and safety, fine inhalable particles with diameters smaller than 2.5 micrometres, or PM2.5, are tracked. Here is the link to the USA Fire and Smoke map https://fire.airnow.gov/ which covers all of North America. Fire symbols show the fires and colour-coded dots indicate the air quality index (AQI) over cities. Grey shading shows the current smoke distribution. Click any dot to view the air quality and plot a graph of recent history.

Fine particulate matter, including smoke, can severely reduce the transparency of the atmosphere. A heavy load will all but obscure views of deep sky objects, especially the faint galaxies and nebulae. The brightest open star clusters and brighter globular clusters may still be visible in binoculars or a telescope, depending on the severity of the contamination. Bright double stars, the moon, and the bright planets should remain visible, too – but their fainter features, such as the moons of Saturn and fine details on the moon, may not be.

The quality astronomy weather forecasting apps also track and predict smoke conditions. Before planning your observing session or heading to a remote site with your telescope, check the clouds AND the smoke. The sky transparency (the second row of hourly boxes) on www.Astrospheric.com is coloured white when the sky is poor and dark blue when it is good for viewing. (Regular clouds make the boxes white, too.) The map at the top of the screen has buttons to display various layers, including smoke (red is severe, grey is clear). Any of those data sets can be run forward in time.

A final thought. Smoke soot (and spring pollen, for that matter) can deposit on optics. Cap your glass surfaces when not viewing and consider cleaning them after exposure to contaminants.

Noctilucent Clouds

The period from late May to mid-August, and especially around the June Solstice, is the best time for mid-Northern latitude observers to watch for noctilucent clouds (NLC) in the hours before sunrise and after twilight, especially when there is no bright moonlight. Those are very high clouds that form in the mesosphere layer of Earth’s atmosphere, 80-82 km above the ground. That’s high enough to catch and reflect sunlight while conditions are dark at ground level. Another name for them is polar mesospheric clouds (PMC).

The clouds form when very cold water vapour that develops in the stratosphere diffuses upwards and freezes around meteor dust particles that are descending from space. The mesosphere is coldest around the solstice. Visually, the clouds will appear as bright, cirrus-like ripples across the lower third of the northern sky, often tinted a silver-blue. If you see dark wisps of clouds overhead, those are regular cirrus clouds.

According to this terrific article from RASC, the first cloud sightings in North America were reported in 1933. The phenomenon may be increasing in frequency as climate change alters the upper atmosphere. More information, and a current polar map of the NLC coverage, can be viewed down the left-hand column of www.spaceweather.com. If you see them, or photograph them, tag me!

The Morning Moon

Since the moon will be sliding sunward in the morning sky this week, everyone on Earth will experience moonless evenings and dark nights – ideal conditions for seeing the stars and deep sky objects of late spring and early summer. Unfortunately, next week’s June solstice means that folks living at mid-northern latitudes won’t see more than the brightest stars until after 10:30 pm – and true darkness will begin about an hour later. Those times shift even later if you live north of 43° latitude. For example, it never gets fully dark in June and July in Calgary, Canada and places in Europe and Asia north of Brussels, Belgium, including London, UK and Kyiv, Ukraine.

Early risers and morning strollers will see our natural satellite during the first part of this week. The pretty, 33%-illuminated, waning crescent moon will rise during the wee hours of Monday morning. It will shine between the bright gas giant planets Saturn and Jupiter until those planets fade with the sunrise. Then the ghostly form of the moon will cross the daytime sky – culminating due south at 9 am local time and then setting early on Monday afternoon.

On Tuesday morning, the moon in central Pisces (the fishes) will pose to the upper right of bright Jupiter. On Wednesday morning, when its slender, elderly crescent clears the treetops around 4 am local time, it’ll be positioned just a few lunar diameters to the left of Jupiter. They will make a spectacular sight – or a lovely photo when composed with some foreground scenery. The Moon and Jupiter will be cozy enough to share the view in binoculars. A low power telescope will show you our moon plus Jupiter’s row of four Galilean moons at the same time. You’ll be able to see the moon and Jupiter until almost sunrise and in daylight – if you can locate them. Check the forecast and set the alarm!

Before sunrise on Thursday and Friday morning, the slim moon will appear 1.5 and 2.7 fist diameters, respectively, to Jupiter’s lower left (or celestial east-northeast). For most of us that will be our last glimpse of Luna. But observers at tropical latitudes can try to see the small dot of the planet Uranus shining just two moon-diameters to the right of the moon on Thursday morning, and the brighter dot of Mercury sitting a slim palm’s width below the moon on Friday. On both mornings the bright little Pleiades Cluster will sparkle nearby before dusk. Turn binoculars and telescopes away from the eastern horizon well before the sun rises.

The moon will be completely out of sight on Saturday. On Sunday at 12:37 am EDT or 04:37 Greenwich Mean Time, the moon will officially reach its new moon phase. At that time our natural satellite will be located in Taurus (the Bull), and about 3 degrees north of the sun. By the time the sun sets on Sunday evening in the Americas, the young crescent moon will have slid far enough east of it to be glimpsed just above the northwestern horizon after sunset. The moon will set an hour after the sun. Seeing a crescent moon less than 24 hours after new is a bucket list challenge for astronomers! Don’t hunt for it with binoculars until the sun has fully set, though.

The Planets

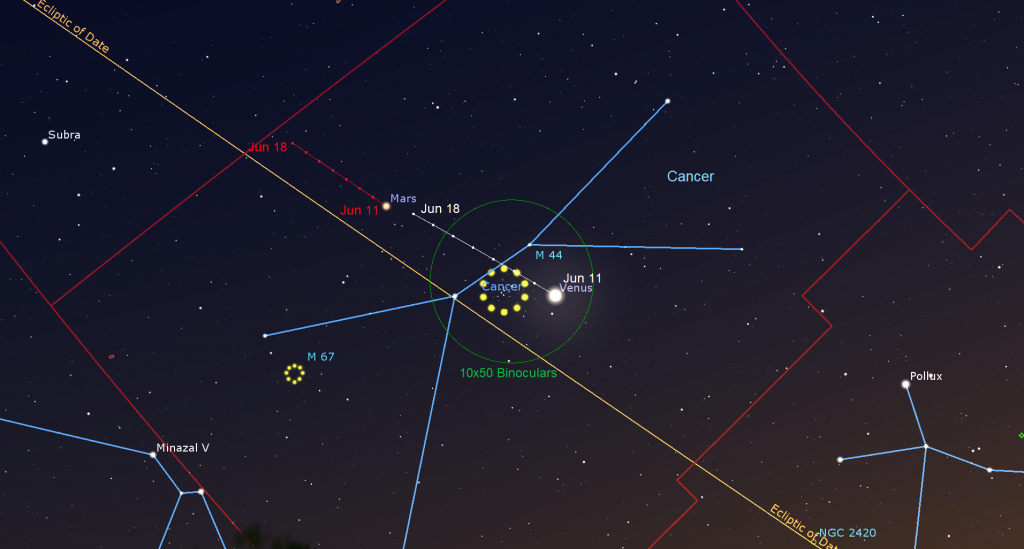

The planets Venus and Mars continue to be alright at night! The duo will make their exit from the western evening sky in a handful of weeks. For now they are dancing together among the weak stars of Cancer (the Crab).

The brilliant dot of Venus will grab your attention in the lower third of the western sky as the sky begins to darken following sunset. Before long the brightest stars of Gemini, golden Pollux and whitish Castor, will appear about 1.5 fist widths to Venus’ right (or celestial northwest). Regulus, the brightest star in Leo (the Lion), will twinkle about 2.5 fist widths to Venus’ upper left. The reddish speck of Mars will shine weakly between them. As the distant stars are carried sunward (by four minutes’ worth) each evening, Venus and Mars will seem to climb “higher” compared to them – but that’s illusory. From now on both planets will drop a little lower in the sky when viewed at the same time each evening. Venus and Mars will set around midnight

Viewed in a telescope this week, Venus will display a half-illuminated disk that is growing slightly larger each day. To see the planet’s shape most clearly, wait until the sun has fully set and then aim your telescope at Venus while the sky is still bright. That way Venus will be higher, shining through less intervening air, and her glare will be lessened. Even good binoculars can hint at Venus’ non-round shape. Like Venus, Mars will look best in a telescope while it is highest, right after dusk, but its ruddy disk will look tiny under any magnification.

Like Mars before it, Venus will pass close to the northern edge of the large open star cluster in Cancer known as the Beehive or Messier 44 this week. The cluster, which covers a patch of sky two times wider than the full moon, is frequently visited by the moon and planets because it is located close to the ecliptic. After dusk on Sunday and Monday night, use binoculars to see the cluster’s stars sprinkled to the left of Venus. On Tuesday, Venus will shine nearest to their top (northern) edge. From Wednesday onwards, Venus will climb away from the cluster, but they’ll still share binoculars until next Monday.

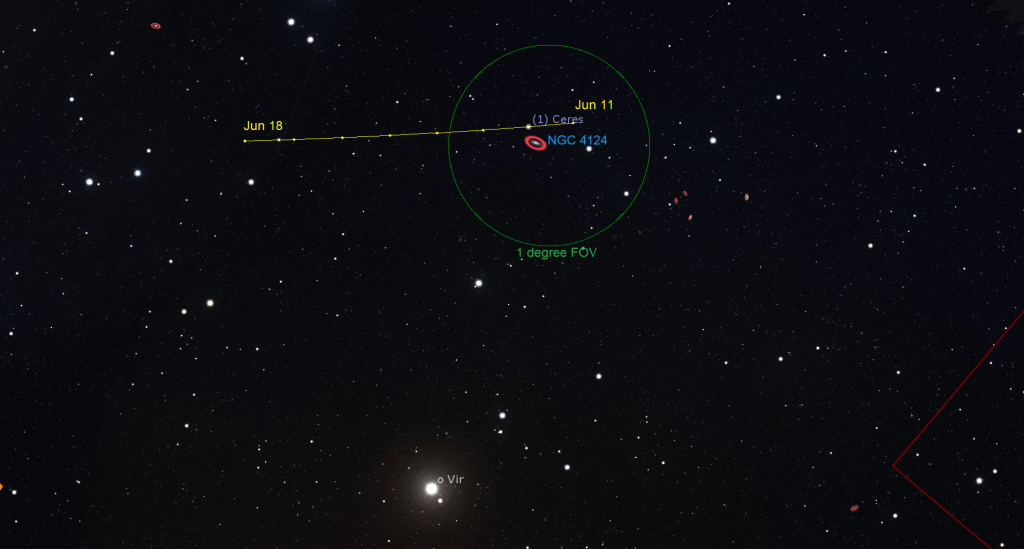

During March Ceres, the largest object in the main asteroid belt, passed close to several bright galaxies when its orbital motion carried it through the Virgo Cluster of Galaxies – setting up some nice photo opportunities. Now Ceres is travelling east again, although below (south of) the main cluster, and will again move close to some nice galaxies. Tonight (Sunday) and on Monday, telescope-owners can see the magnitude 8.2 minor planet, which is also visible in full-sized binoculars, positioned just above the spiral galaxy NGC 4124. They’ll share the eyepiece until Thursday – so you have several chances to catch sight of the meeting. Ceres will be in the southwestern sky, a palm’s width to the left (or 6° to the celestial southeast) of the very bright star Denebola, which marks Leo’s tail, and a thumb’s width above the less-bright star Omicron Virginis.

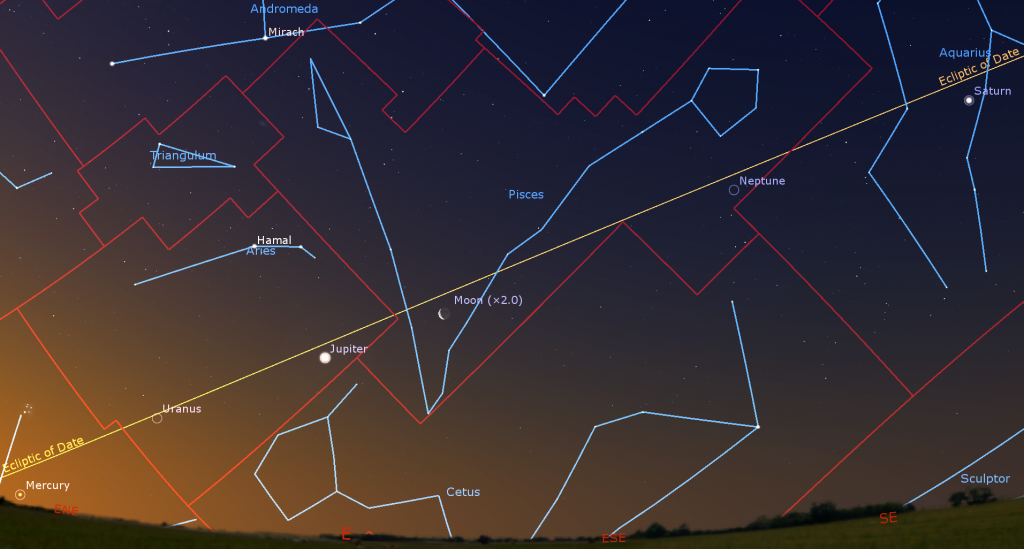

The morning sky is busy this week! The moon plus three bright planets, two fainter planets, and the asteroid Vesta are all gathered along the ecliptic in the pre-dawn sky.

Bright, yellowish Saturn will clear the trees towards the southeast after about 2 am local time. This morning (Sunday), Saturn ceased its regular eastward motion through the distant stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and began a retrograde loop that will last until early November. The apparent reversal in Saturn’s motion is an effect of parallax produced when Earth, on a faster orbit, passes the ringed planet on the “inside track”. You can observe Saturn’s motion by noting how its distance from the nearby bright stars Hydor (Lambda Aquarii) and Deneb Algedi (Delta Capricornus) varies over the coming weeks. You’ll lose sight of the planet altogether around 5 am. In a few weeks, Saturn will start rising before midnight. Then it’ll be available for our evening enjoyment until mid-winter!

The planet Neptune, which is located in western Pisces (the fishes), is positioned two fist diameters to Saturn’s lower left (or 20° to the celestial east). The distant blue planet is 600 times fainter than Saturn, though. We’ll get nice views of Neptune in backyard telescopes from August onwards.

The brilliant white dot of Jupiter, about 16 times brighter than Saturn, will rise around 3 am. It will clear the eastern rooftops just as the sky starts to brighten before 4:30 am and remain in sight until almost sunrise. In a few weeks, though, Jupiter will rise early enough to shine in a dark sky amid the stars of its host constellation, Aries (the Ram). Jupiter will start to rise before midnight by the second week of August, and we’ll be able to view it from then until March, 2024. Don’t forget to catch the waning crescent moon passing Jupiter from Monday to Wednesday morning.

Binoculars will show Jupiter’s four Galilean moons lined up beside the planet. Callisto, one of those moons, will pass closely below (south of) Jupiter on Saturday morning. A small telescope will show the bands on the planet and the Great Red Spot (or GRS) every second or third day.

From time to time, observers with good quality telescopes can watch the small, round, black shadows of the four Galilean moons travel across Jupiter’s disk. On Sunday morning, June 18, observers with good telescopes in central North America can watch the shadow of Io cross the equatorial region of Jupiter along with the Great Red Spot! At 3:30 am CDT or 08:30 GMT, the shadow of Io will begin its crossing closely beside the Great Red Spot. Before long, Io’s shadow will overtake the spot and then lead it the rest of the way across Jupiter. The shadow of Europa will appear at 5:28 am CDT, shortly before Io’s shadow leaves the planet.

Uranus will be positioned 1.5 fist diameters to the lower left of Jupiter this week. Have a look for it while the waning crescent moon shines just to its upper left on Thursday morning. The blue-green planet will become much easier to see in the coming weeks.

Mercury is also in the pre-dawn sky. If you have a cloud-free, unobstructed view to the east-northeast, look just before sunrise for its medium-bright dot positioned just above the horizon. Turn your binoculars away before the sun rises. Observers in the tropics will see Mercury much more easily.

Eyeing Ophiuchus

This week’s moonless nights will be great for stargazing, so I’ll highlight the best sights to see inf the lesser-known constellation of Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer). But first – an aside about the zodiac.

The twelve constellations of the zodiac are only famous and/or special because the great circle of the ecliptic carries the sun through each of them. The sun spends varying amounts of time crossing each constellation, and the entry and exit dates repeat every year. For example, in the present era, the sun traverses the constellation of Gemini (the Twins) from June 21 to July 19. (Remember, the sun isn’t moving – Earth’s orbital motion makes the sun appear to change location with respect to the fixed distant background stars.)

If you’re an astrology enthusiast, you’ll be wondering by now – why is the sun traversing Gemini in June and July if the “star sign” for birthdays between May 22 and June 21 is Gemini? Well, thousands of years ago, when astrology was formulated by the Greeks and Babylonians, the sun did traverse the stars of Gemini during that part of the year. It’s one of many reasons why most astronomers place no value in astrological predictions. By the way – if you have an astronomy app or program that allows the year to be changed, you can set the app to noon, centre the sun, and then change the date to June 21st of 400 BCE. The sun will land on the border of Cancer (the Crab), which sits east of Gemini!

Most of the zodiac constellations are inconspicuous, if not nearly invisible, from the city and suburbs. Aries (the Ram) has two decently bright stars that form a little stick, while Cancer, Pisces (the Fishes), Aquarius (the Water Bearer), and Capricornus (the Goat) are seriously tough to make out – unless you travel to darker skies. A few constellations, Gemini (the Twins), Taurus (the Bull), Scorpius (the Scorpion), and Leo (the Lion), have very bright stars that form easily recognizable shapes. The rest of the dozen fall into the medium-bright range.

You may be surprised to learn that there is a thirteenth zodiac constellation! Late June is a good time to observe it, because that’s when it’s opposite the sun in the sky. Ophiuchus (“Oh-fee-YOU-cuss”), the Serpent Bearer is a huge constellation (11th largest by area). It sits above and between (celestial north of) the Teapot-shaped asterism of Sagittarius (the Archer) and Scorpius. Lyra (the Lyre) and Hercules are above it. The ecliptic crosses the southernmost (lower) stars of Ophiuchus – but Ophiuchus has never been considered part of the zodiac because that would exceed the special system of 12 sky divisions important to ancient astrologers. If it were included, December babies would be Ophiuchans! In China, Ophiuchus is considered part of 天市左垣 (Tiān Shì Zuǒ Yuán), the Left Wall of the Heavenly Market Enclosure.

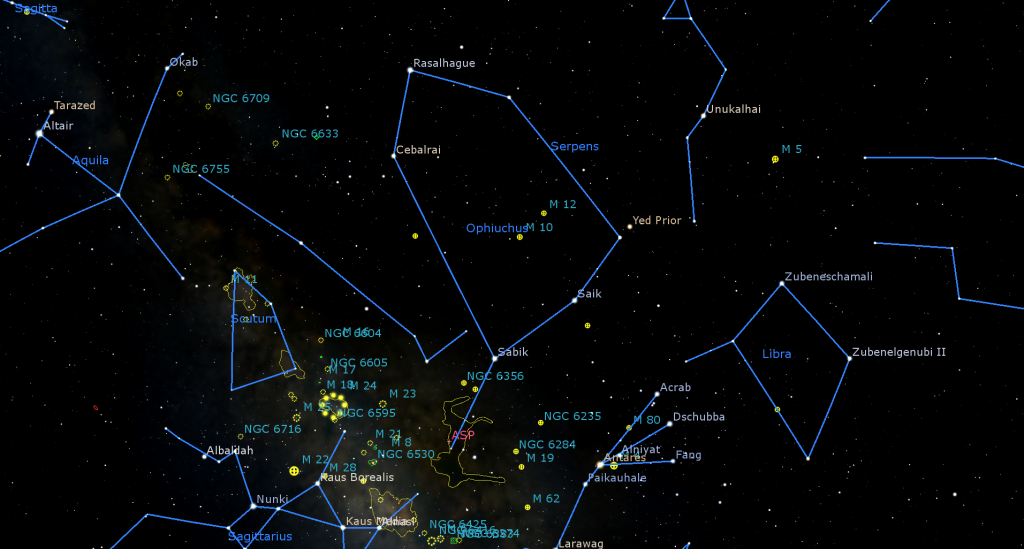

Ophiuchus’ stars are only medium-bright – so it’s another constellation that is better to trace out when the sky is darker. The constellation’s shape resembles a large, upright box (26° tall and 16° wide) with a pointed triangle forming the upper edge. (Think of a Dalek from Doctor Who.) The constellation’s brightest star, Rasalhague, from the Arabic raʼs al-ḥawwā, “the head of the serpent charmer”, marks the peak of that triangle. Rasalhague is located about midway between the very bright stars Vega and Antares. Rasalhague is a binary star system located about 48 light-years away. One of the two stars is spinning almost fast enough to break apart.

Ophiuchus’ second brightest star Cebalrai ”the shepherd’s dog” marks his eastern shoulder almost a fist’s diameter below (south of) Rasalhague. Also designated β Oph, magnitude 2.7 Cebalrai is an old sunlike star that has evolved to the stage where it has swelled and cooled to give it an orange colour. It is 82 light-years away. Ophiuchus’ western shoulder is marked by somewhat fainter Kappa Ophiuchi (or κ Oph). It, too, is almost a fist diameter from the head – toward celestial west – and it has also evolved to a cooler stage.

Immediately east and west of the main body of the Serpent-Bearer are two long sections of a separate, split-in-two constellation named Serpens. It’s the Serpent that Ophiuchus is bearing! The western (right) half is called Serpens Caput (the Snake’s Head), while the eastern (left) portion is Serpens Cauda (the Snake’s Tail). The Serpent-Bearer stands on the head of the scorpion, Scorpius. In Greek mythology, Ophiuchus saved Orion (the Hunter) from that creature’s venom. The bright stars of the Summer Triangle asterism are located to the upper left (celestial northeast) of Ophiuchus.

From east to west (left to right when viewed from the Northern Hemisphere), the stars forming the bottom of Ophiuchus’ boxy form are: medium bright Sabik “the preceding one”, dimmer Zeta Ophiuchi (or ζ Oph), and two dimmer stars a finger’s width apart named Yed Prior “leading hand” and Yed Posterior “trailing hand”. They represent his western hand. Yed Prior, the westernmost of the two, is extremely red in colour. Sabik is the star that Uranus’ northern axis of rotation points towards – the role played by Earth’s own pole star, Polaris! About a palm’s width to the upper left of the Yeds sits Marfik “the elbow” or λ Oph. When viewed in a telescope, 170 light-years-distant Marfik splits into a close-together pair of white stars.

You’ll need an astronomy app and a small telescope to see it, but Ophiuchus is home to Barnard’s Star – a magnitude 9.5, red dwarf star located six light-years away from us. It is the fourth closest known star, and the closest star visible from the northern hemisphere. Barnard’s Star is located 3.5 finger widths to the left (or celestial east) of Cebalrai. Because it is so close to our solar system, we can actually watch Barnard’s Star travel through the galaxy in a process known as proper motion. It moves 10.3 arc-seconds per year, or about half the moon’s diameter in a human lifetime.

A handful of medium-bright stars are spread out to the lower left (celestial east) of Cebalrai. They form the gentleman’s pipe or flute – or the Dalek’s disruptor! Use binoculars to find the small, bright, open star cluster named IC 4665 located just to the upper left (or celestial north) of Cebalrai.

Because Ophiuchus sits just above the plane of the Milky Way, it is chock full of globular star clusters – spherical, tightly packed groups of stars that orbit our galaxy tens of thousands of light-years away from us. A large, reasonably bright one designated Messier 10 sits just about where the Serpent-Bearer’s belt buckle would be – with a slightly dimmer one Messier 12 to its upper right. Another bright globular named Messier 107 is located just below Zeta Ophiuchi, and another named Messier 14 sits about midway between Sabik and Cebalrai. You can see the clusters in binoculars or a small telescope, especially from a dark sky site.

A little group of medium-bright stars, dominated by one brighter star named Garafsa or Theta Ophiuchi (or θ Oph), sit about a fist’s diameter to the lower right (or 10° to the celestial southeast) of Sabik. Those stars mark Ophiuchus’ eastern foot and are very close to the ecliptic. The Dark Horse, or Prancing Horse, is a dark dust region of the Milky Way that surrounds Garafsa. Measuring a fist’s diameter tall and several finger widths across, it can be captured in long exposure images. It can also be seen visually from southerly latitudes, where the constellation climbs higher in the sky.

The southeastern (or bottom) part of Ophiuchus dips into the Milky Way – so there are many more star clusters there. The star Rho Ophiuchi (or ρ Oph) in the southwestern corner of the constellation near the bright star Antares is gorgeous in long exposure photos. But even a small telescope will show Rho as a double star surrounded by even more stars! After midnight local time this week, the centre of Ophiuchus will be due south and located about halfway up the sky. Let me know if you check it out!

A Glance at Globular Clusters

If you missed last week’s guide to Globular star clusters I posted it with finder charts for many of the best clusters here.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcast with RASC National returns on Tuesday, June 20 at 3:30 pm EST. We’ll focus on how to use star charts and which ones are best. Then we’ll highlight our next batch of RASC Finest NGC objects. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!