Some Sky Light Lore, Autumn Arrives for Northerners, Several Planets Peak, and the Moon Looms in Evening!

This fantastic image of the Heart and Soul Nebulae in Cassiopeia was captured by my friend Steve Mallia at Starfest in Ayton, Ontario on September 15, 2023. The pinks are produced by ionized hydrogen gas and the blues by starlight scattering from interstellar dust. The entire scene spans about a palm’s width the sky. Despite their size, the emission nebulae are too faint to be readily seen with human eyes, even in backyard telescopes. More details about Steve’s image is here.

Hello, Autumn Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of September 17th, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! I’m proud of my book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope. It’s a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

Autumn in the north and spring in the south will officially arrive on Saturday. I explain why Venus will peak in brightness this week, and so will Neptune and Mercury – but for different reasons. The pretty moon will wax in evening, Saturn and Jupiter will shine overnight, and the morning zodiacal light will be visible from very dark sites for a while yet. Read on for your Skylights!

Lights in the Sky

The stars at night are visible because they are emitting visible light produced when energy produced by atoms fusing in their interiors makes its way out of the star. Those photons of light then journey across the vast reaches of space for years – or centuries – or even millennia, end then enter your pupils and excite the rods and cones in your eyes – a fascinating blend of physics, chemistry, and biology. We can also see the combined light from millions or billions of stars collected into the plane of our home Milky Way galaxy or the glow of individual, distant galaxies. We also see nebulae – glowing ionized gas clouds that will one day shine as new stars. Some of those nebulae are within the Milky Way, but we can see nebulae in other galaxies, too.

Much closer to home, the various denizens of our solar system only become visible to us when our star, the sun, shines it light on them. Sunlight reflected off them and sent in our direction lets us see the planets and asteroids, the dust of a comet’s tail, and even the dust particles sprinkled between the planets (zodiacal light). While not reflected sunlight, the aurora (borealis and australis) are nevertheless produced by the sun’s energy interacting with Earth’s magnetic field. The only natural sky phenomenon I can think of that isn’t produced by starlight in one way or another is meteors.

I bring this up because of a worldwide event that will happen this week. For several hours before sunrise on Tuesday morning, September 19, the brilliant planet Venus will shine in the eastern sky at its greatest illuminated extent for the current morning apparition. What does that mean?

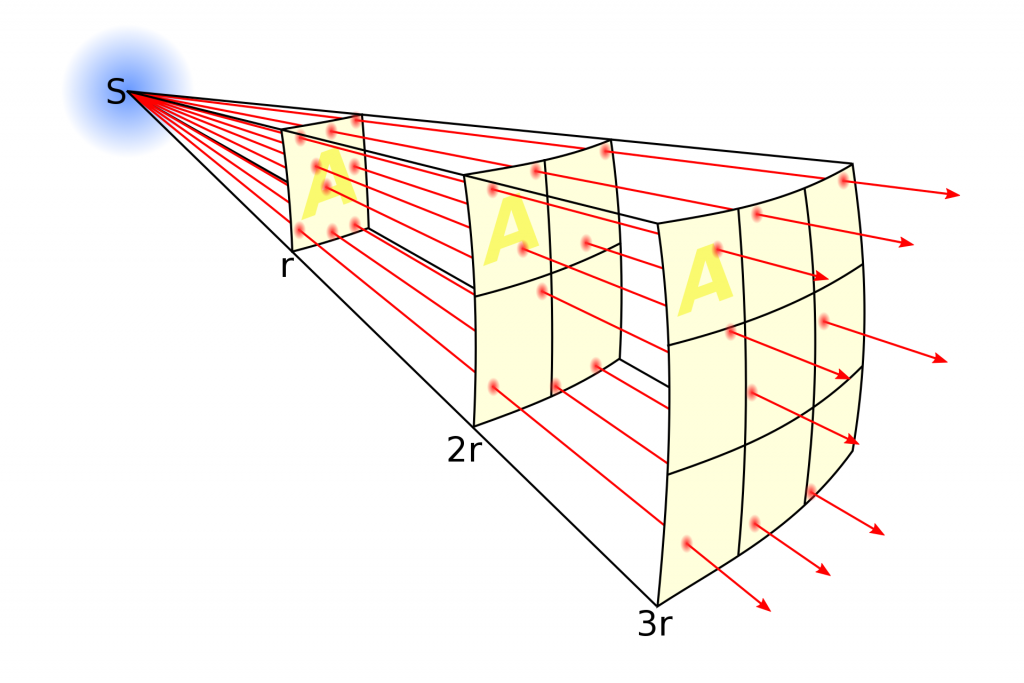

How bright a planet looks is controlled by several factors. Unobstructed light from a source spreads out in all directions. Since the same amount of light has to cover a larger and larger area the farther from the source it travels, its intensity falls off as the square of the distance. In other words, twice as far means a quarter as bright. In the case of reflected sunlight, the intensity of the light shining on a planet is lower when it’s farther from the sun – and then its reflected light gets spread out and reduced even more according to how far it is from you!

If the Earth-facing hemisphere of a planet (or the moon) is entirely illuminated, half of its surface area will catch and reflect that light towards you, making it the brightest it can be. That’s the case of a full moon or a planet at opposition. But if the sun is shining on the object from the side or some other angle, then only a part of its Earth’s-facing side is lit up, producing phases. The smaller the illuminated area is, the less bright it will look.

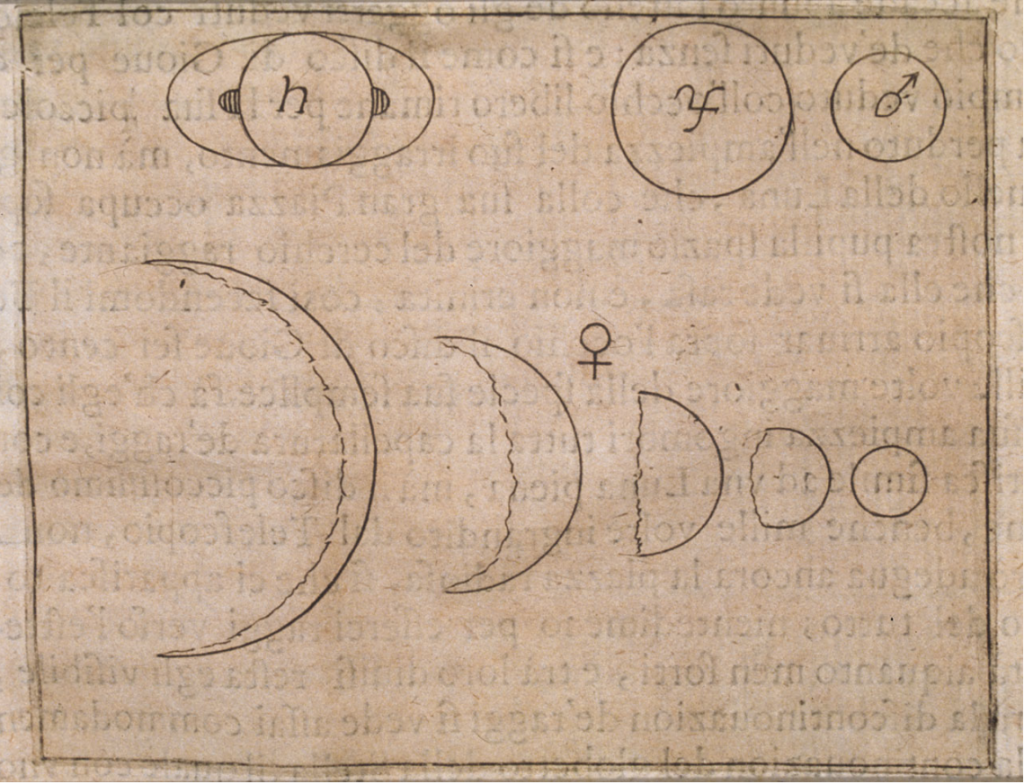

Ancient astronomers noticed that Venus looked brighter and fainter at times. Galileo, who was one of the first to use a telescope to magnify Venus, discovered that Venus displayed phases similar to the moon. Studying it over many weeks, he saw that Venus’ illuminated phase varied as its angle from the sun changed – but he also saw that Venus changed size, too! We now know that Venus’ varying distance from Earth produces a range of apparent size spanning 66 arc-seconds when it is closest to us and 10 arc-seconds when it’s farthest away from us on the far side of its orbit from Earth. (In comparison, the moon’s apparent size is about 1,920 arc-seconds.)

The apparent size of a planet and its illuminated phase combine to produce its brightness in the sky. Greatest illuminated extent is said to occur when those two factors make a planet looks brightest. In a telescope on Tuesday morning, Venus will show a 27%-illuminated, waxing crescent phase and an apparent disk size of 38 arc-seconds. Even with a less than fully-illuminated disk, Venus’ nearness to Earth of only 0.442 Astronomical Units (the mean sun-Earth separation) or 66.06 million km will boost its brightness to a brilliant magnitude -4.76. That’s not quite the brightest Venus ever gets – but close to it.

Don’t fret if the sky is cloudy on Tuesday. Venus will be almost as bright from now (Sunday) to Wednesday. And if you prefer an evening view, Venus will next reach greatest illuminated extent in mid-February, 2025.

I’ll talk a little more about planets’ peak brightening below.

Equinox

On Saturday, September 23 at 2:50 am EDT or 06:50 Greewich Mean Time, the sun’s apparent motion along the ecliptic will carry it across the celestial equator traveling southward, marking the autumnal equinox in the Northern Hemisphere and the beginning of autumn there and spring in the Southern Hemisphere.

Allow me to elaborate…

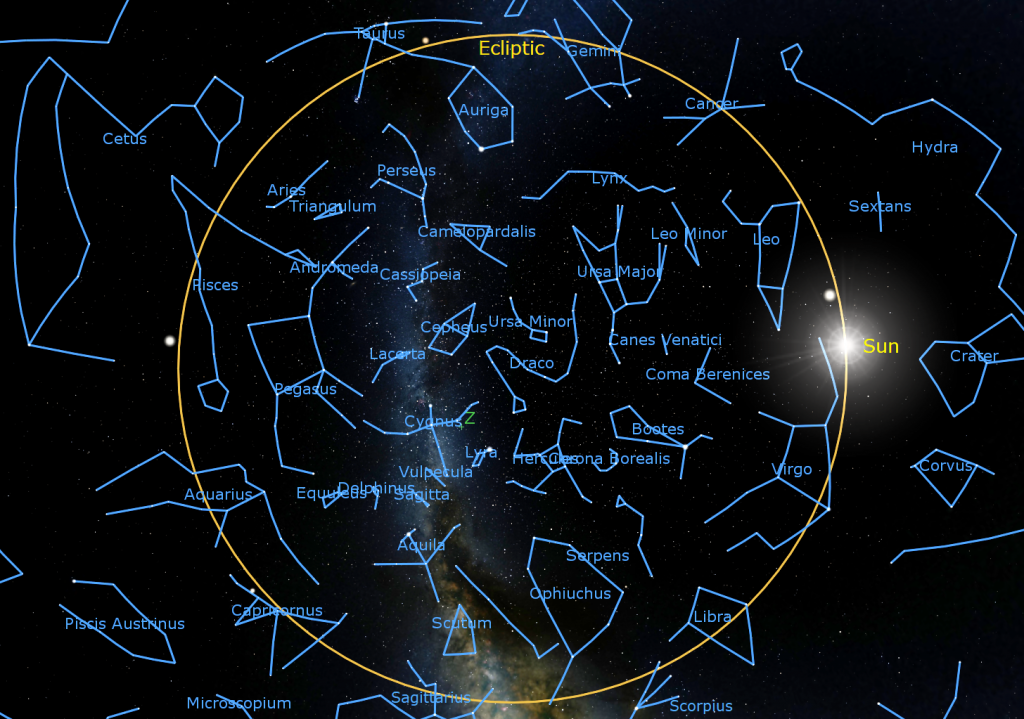

As the Earth travels around the sun (completing one orbit every year), our perspective change makes the sun slide continuously eastward across the distant background stars. The circular path it traces around the celestial sphere is called the ecliptic. Ancient skywatchers noted that, in the course of one year, the sun passed through the same twelve (well, thirteen actually) constellations – avoiding all others. Those “special constellations” became the zodiac. The sun’s time spent within each zodiac constellation fell onto the same range of dates – leading to the astrology sun sign idea that many still follow.

The sun doesn’t precisely “re-trace its steps” every year. You see, the Earth, as a “spinning top”, is precessing. That’s because it is not a perfect sphere and the sun and moon tug on those imperfections. Earth’s two polar axes (one north and one south) each point to a spot on the sky called the celestial pole. Earth’s northern axis is currently aimed 27.5 arc-minutes (about the moon’s apparent diameter) away from Polaris, the North Star. That’s close enough for regular folks to use Polaris as the north celestial pole, but astronomers’ telescopes need to be precisely aligned to the true pole.

Earth’s precession has – and will continue to – trace out a circle of 47° in diameter in the stars over an interval that repeats every 25,765 years. During that cycle the celestial pole will pass through through the constellations of Ursa Minor (the Little Bear), Cepheus (the King), and the northern parts of Cygnus (the Swan), Lyra (the Harp), and Hercules. The very bright star Vega will mark the pole again around 13,500 AD.

The precession ring almost completely encloses the constellation of Draco (the Dragon) and passes closer to its star Thuban than it does to Polaris. In fact, the northern polar axis of the sun and many of the major planets point to parts of Draco. The indigenous people of North America have long envisaged Wakiåyaå, a great Thunderbird constellation, inside the precession circle, evidence for the great length of time they have been watching the skies and their understanding of the changes that occur over many thousands of years!

The Earth’s precession also makes the sun creep westward along the ecliptic by 50.2 arc-seconds per year, or about a thumb’s diameter every century. Several thousand years ago, the equinoxes were called the First Point of Aries and the First Point of Libra because those constellations hosted the sun in March and September. Since then, precession has caused the two equinox points to shift by one zodiac constellation to the west.

Okay – let’s get back to talking about the September equinox…

The Earth’s axis of rotation is tilted 23.5° away from the ecliptic – so an imaginary circle painted on the sky directly overhead of our equator passes through a different group of stars than does the ecliptic. In fact, that celestial equator divides the celestial sphere into two great bowls comprising the Northern Hemisphere stars and the Southern Hemisphere stars. Since the Earth’s equator is to the south for observers in the Northern Hemisphere, the celestial equator is always in the southern region of our sky, and it arcs from the eastern horizon to the western horizon.

You can think of the equator and ecliptic circles as two hula hoops sharing the same centre – us. Since one hoop is tilted by 23.5° compared to the other one, the two circles only intersect at two spots in the sky, one in western Virgo (the Maiden) and the other in western Pisces (the Fishes). The sun reaches those spots during the third weeks of March and September, respectively. Another way of thinking about it is that half of the ecliptic runs through stars in the southern celestial hemisphere, and the other half runs through northern stars – so the sun spends half of the year among northern stars and the other half among southern stars.

At an equinox, the sun occupies one of the two intersection points – as if it is “stepping over” the equator. The full disk of the sun takes about 13 hours to cross the equator – but we define the equinox as the precise moment when the centre of the sun slips across. The equinoxes and solstices are global events. Just correct by the appropriate number of hours to determine when northern autumn will begin in your own time zone.

On the September, or autumnal, equinox the sun is passing into the southern bowl of the sky. Six months later, on the vernal equinox, it will cross the celestial equator at the other intersection point and re-enter the northern bowl of the sky. At that moment, spring will begin for the Northern Hemisphere. (I like to avoid using the seasonal terms “vernal” and “autumnal” because those seasons are swapped for people living in the Southern Hemisphere.) The solstices occur about mid-way between the equinoxes – in late June and December.

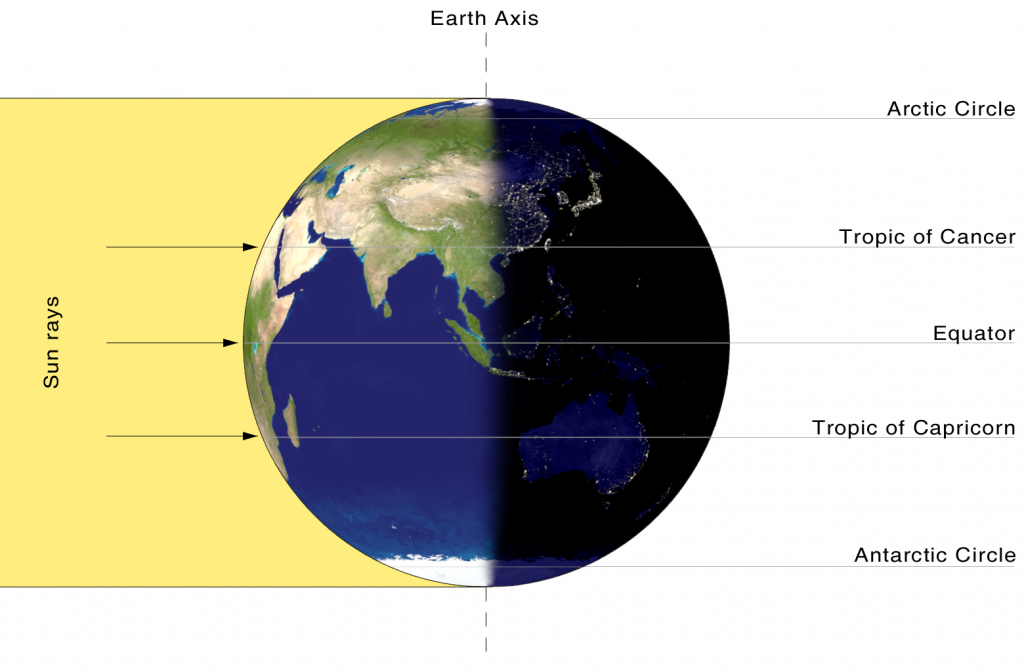

An equinox produces several interesting effects. At either equinox, the sun rises due east and sets due west. For the six months following the September equinox, the sun will spend all of each day among the Southern Hemisphere stars, and climb high in the sky for the lucky folks who live there! The higher sun will take more daylight hours to cross the sky and will deliver more highly-concentrated solar radiation, producing warmer weather. (Compare the intensity of a flashlight’s light when it’s beamed straight at a wall versus obliquely at the wall. The bright circle of light gets weaker when it’s spread into an oval.) During the same months, North Americans, Europeans, and Asians have to accept shorter, colder days and longer nights (which are great for warmly dressed astronomers). On the day of the equinox, everyone on Earth experiences 12 hours each of day-time and night-time (unless you live near the North Pole where the sun won’t drop low enough below the horizon to darken the sky). This is where the term equinox, Latin for “equal night”, comes from.

The nights around the equinoxes offer a higher likelihood of the Northern Lights, or aurorae, at high northern and southern latitudes. Just as two bar magnets lined up with their poles in the same direction repel one another strongly, the Earth’s magnetic field repels the sun’s field. At the equinoxes, the Earth’s axis tilts partly sideways compared to the sun, so those two “magnets” aren’t lined up as well, reducing Earth’s ability to deflect the sun’s field and the charged particles that trigger aurorae in our upper atmosphere.

At this time in September every year, the Earth is travelling almost directly towards the stars that mark the upraised club of Orion (the Hunter) and the toes of Gemini (the Twins). In a few weeks, that geometry will produce the “bugs on a windshield” effect when the Orionids meteor shower particles strike the Earth’s upper atmosphere and produce the streaks of light we see. Also at this time, Earth is travelling almost directly away from the stars of Sagittarius (the Archer) and Ophiuchus (the Water-Bearer).

What I’ve described above forms the astronomical definition of the seasons. The dates that each season begins on each year vary a little because Earth’s year is 365.2425 days. That extra 5.82 hours per year adds up until we eliminate most of it using the February 29 Leap Day every four years. The rest of the fraction is cleaned up by skipping Leap Day on most of the years that end with “00”. The meteorological definition of the seasons declares that northern autumn begins on September 1 and ends on November 30 – and so on through the year for winter, spring, and summer.

The Moon

This is the best week of the lunar month to enjoy our natural satellite in the evening sky worldwide. The moon will be rising in the daytime and following the sun across the sky. As the week unwinds the moon will increase its angle from the sun, wax in illuminated phase, and linger longer after the sun sets. Use binoculars or any size of telescope to magnify the moon alongside the terminator. That’s the boundary between the lit and unlit portions of the moon’s disk. Slanted sunlight arriving there will make the terrain look spectacular. The terminator’s migration across the waxing moon every night will highlight something new to enjoy.

After sunset tonight (Sunday) the moon will appear as a thin sliver above the west-southwestern horizon. The stars of Virgo (the Maiden) will surround it, but none of them will be bright enough to see in the twilight.

The moon will be easier to find from Monday onwards. It’ll pass through the constellation of Libra (the Scales) on Monday-Tuesday and then get caught among the claw stars of Scorpius on Wednesday evening. That night, look for the bright, reddish star Antares, the heart of the scorpion, twinkling furiously several finger widths to the moon’s left (or celestial east). The up-down row of small white stars that form the scorpion’s claws will be located to the moon’s right. From top to bottom, they are Jabbah or Nu Scorpii, Graffias or Acrab, Dschubba, Pi Scorpii, and Iklil or Rho Scorpii. A backyard telescope at high magnification will reveal that Nu Scorpii, Graffias, and Dschubba are close-together double stars. On Thursday evening, observers in the region extending south from Japan will be able to see the moon pass in front of (or occult) Antares.

The moon will spend Friday and Saturday crossing the teapot-shaped stars of Sagittarius (the Archer). When it officially completes the first quarter of its journey around Earth on Friday, September 22 at 3:32 pm EDT or 12:32 pm PDT and 19:32 Greenwich Mean Time, its 90 degree angle away from the sun will cause us to see the moon half-illuminated – on its eastern side.

The moon will end this week as a bright, gibbous orb shining among the faint stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) next Sunday night.

The Planets

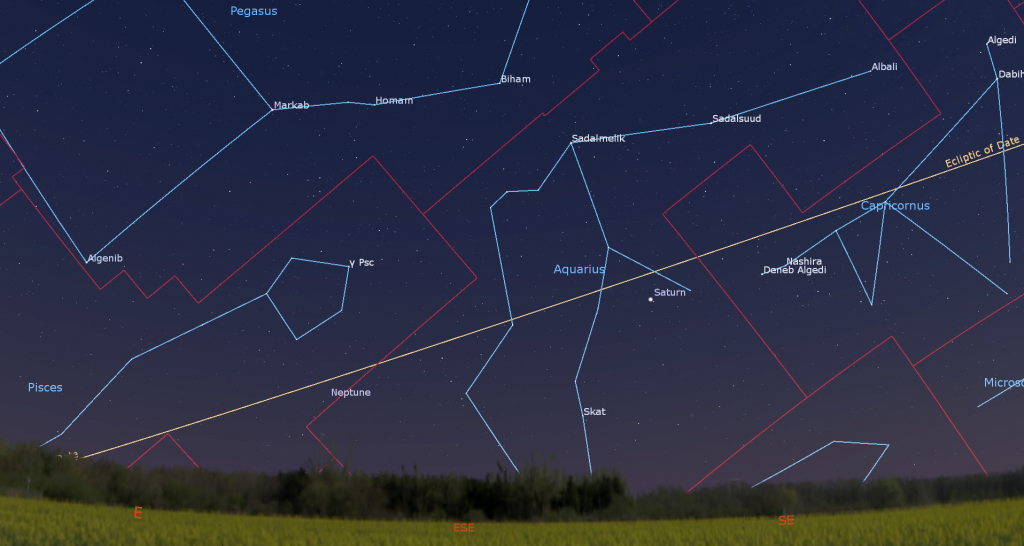

Saturn season will continue into winter! This week, its creamy-yellow dot will pop into view above the southeastern horizon soon after sunset. Recently past opposition and peak brightness, the ringed planet will shine all night long as it crosses the sky. You’ll get the clearest views of Saturn in a telescope when it is higher in the sky – say after 9 pm local time. The faint stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) will be shining to the left and right of Saturn, respectively. The bright trio of the Summer Triangle asterism stars will sparkle well above, and the Great Square of Pegasus stars will be off to the planet’s upper left. The very bright star Fomalhaut (or Alpha Piscis Austrini, the Southern Fish) will shine two fist diameters below Saturn all year long.

Saturn’s beautiful rings are visible in any size of telescope. If your optics are of good quality and the air is steady, try to see the Cassini Division, a narrow gap curving between the outer and inner rings, and a faint belt of dark clouds that encircle the planet’s globe. Remember to take long, lingering looks through the eyepiece – so that you can catch moments of perfect atmospheric clarity. Good binoculars can hint at Saturn’s rings, too.

From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves above, below, and alongside the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the planet’s upper right (celestial west) tonight (Sunday) to close in on Saturn’s left (celestial northeast) next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope? You may be surprised at how many you can see if you look closely.

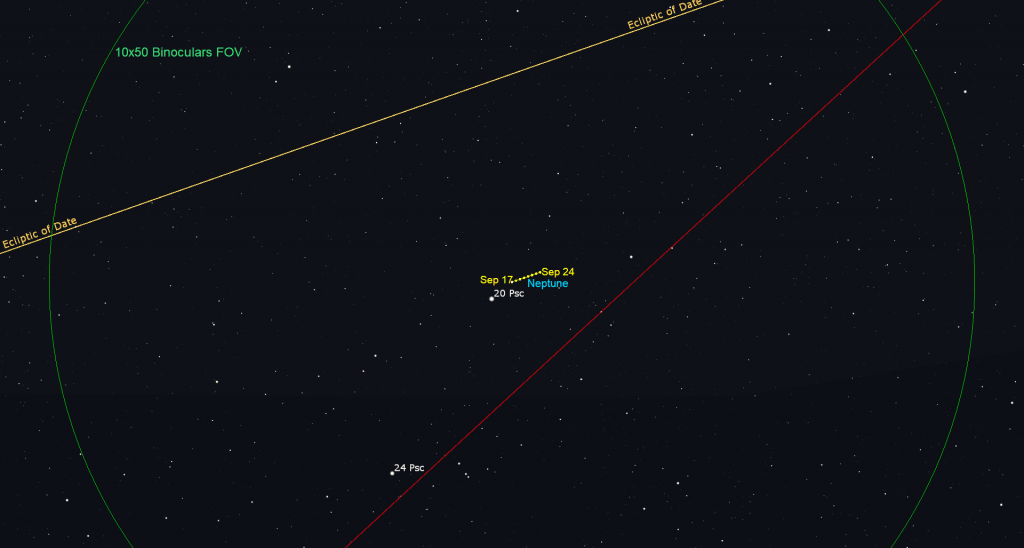

This summer the ice giant planet Neptune, currently 840 times fainter than Saturn, will be lurking 2.4 fist diameters to Saturn’s lower left, or 24° to its celestial northeast. Last week, the blue planet slipped very closely past a brighter star named 20 Piscium. This week that star will be positioned farther and farther to Neptune’s lower left (or celestial east). On Tuesday, September 19, Neptune will reach opposition. At that time the distant planet will be closest to Earth for this year – a distance of 4.32 billion km, 4 light-hours, or 28.9 Astronomical Units. At opposition, Neptune will shine with a slightly enhanced magnitude of 7.8. Since it will be opposite the sun in the sky, Neptune will be visible all night long in backyard telescopes. Good binoculars can show it, too, if your sky is very dark. Your best views will come after 9 pm local time, when the blue planet has risen higher. Around opposition, Neptune’s apparent disk size will peak at 2.4 arc-seconds and its large moon Triton will be the most visible in telescopes.

Brilliant, white Jupiter, which currently shines about 19 times brighter than Saturn, will be clearing the eastern rooftops by about 10 pm local time this week. Good telescope viewing time will begin by 11 pm. Not to worry, though – that window will start earlier and earlier in the coming weeks. This year Hamal and Sheratan, the brightest stars of Aries (the Ram), will shine a generous fist’s diameter above the giant planet. Jupiter will spend the wee hours of the night following Saturn across the sky, then it should catch your eye while it gleams high in the southwestern sky before sunrise.

Binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons in a line beside the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. This week, Jupiter’s westerly retrograde motion will continue to carry it closely past a bluish star named Sigma Arietis (or σ Ari). While that star will appear about as bright as one of Jupiter’s moons, it will shine above (celestial north of) their line tonight (Sunday). Then it will slowly migrate to Jupiter’s lower left (or celestial east) on each subsequent night.

Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk late Eastern Time on Monday, Wednesday, and Saturday night, in the wee hours on Monday, Thursday, and Saturday. It’ll appear before dawn on Wednesday and Friday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Monday morning, September 18, Io’s small shadow will cross Jupiter’s equatorial region from 5:07 to 7:14 am EDT (or 09:07 to 11:14 GMT). Io’s shadow will cross again on Tuesday night, September 19 from 11:36 pm to 1:42 am EDT (or 03:36 to 05:42 GMT on Wednesday). (These times may vary by a few minutes.)

The blue-green ice giant planet Uranus will be following Jupiter across the sky this year. This week Uranus will be located a generous palm’s width to Jupiter’s lower left (or 7.6° to the celestial east). The bright little Pleiades star cluster will be located a similar distance to Uranus’ left. Magnitude 5.8 Uranus is visible in binoculars and small telescopes if you know where to look. I’ll get more specific in the coming weeks when it will climb higher.

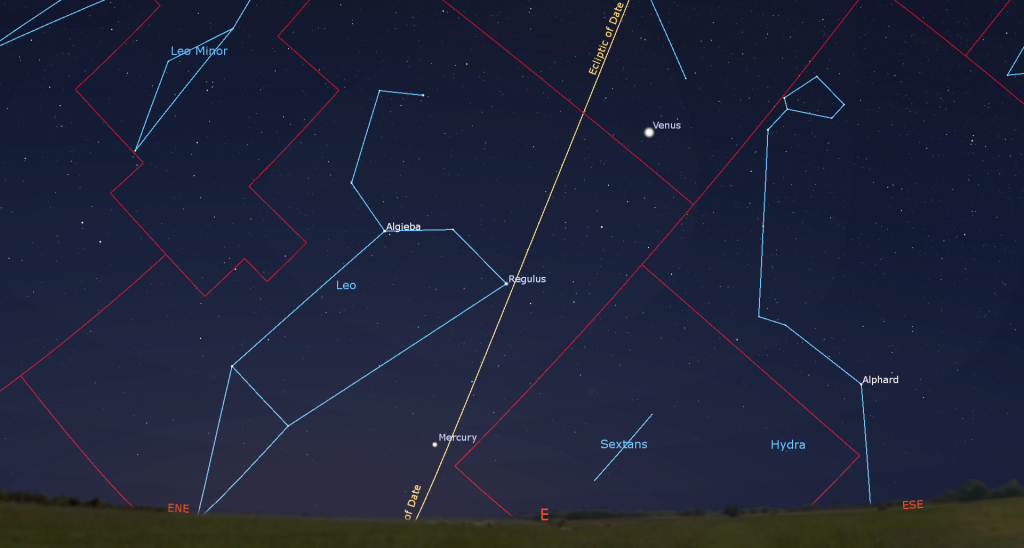

Venus will gleam brightly in the eastern pre-dawn sky from now until January, climbing farther from the sun with each passing day. This week Venus will rise among the stars of Cancer (the Crab) at about 3:45 am local time. Early risers can enjoy the winter constellations and stars nearby. As I mentioned above, our sister planet will exhibit a large disk and a very slim waxing crescent phase in a telescope this week. Turn all optics away from the eastern horizon before the sun rises.

On Friday morning, the planet Mercury will reach a maximum angle of 18 degrees from the sun, and peak visibility, for its current morning apparition. Look for the innermost planet shining brightly while it climbs the eastern pre-dawn sky around 6 am in your local time zone. In a telescope Mercury will exhibit a 48%-illuminated, waxing phase. Mercury’s position above the nearly upright morning ecliptic will make this an excellent apparition for Northern Hemisphere observers, but a very poor one for those located south of the Equator, where the ecliptic will be tipped over.

Morning Zodiacal Light for Mid-Northern Observers

During autumn at mid-northern latitudes every year, the ecliptic extends nearly vertically upward from the eastern horizon before dawn. That geometry favors the appearance of the faint zodiacal light in the eastern sky for about half an hour before dawn on moonless mornings. zodiacal light is sunlight scattered by interplanetary particles that are concentrated in the plane of the solar system – the same material that produces meteor showers. It is more readily seen in areas free of urban light pollution. For observers at low latitudes, the ecliptic is nearly vertical all year round, making the light a frequent phenomenon. Sadly, observers north of 60°N latitude miss out.

If your location favours it, on mornings between now until the full moon on September 29 look for a broad wedge of faint light extending upwards from the eastern horizon and centered on the ecliptic. It will be strongest in the lower third of the sky below the very bright planet Venus, which may suppress the phenomenon. Don’t confuse the zodiacal light with the Milky Way, which will be positioned nearby in the southeastern sky. I posted a simulation of the zodiacal light here.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

Taking advantage of the crescent moon in the sky this week, the RASC Toronto Centre astronomers will hold their monthly City Sky Star Party in Bayview Village Park (a short walk from the Bayview TTC subway station), starting after dusk on the first clear weeknight this week (Mon, Tue or Thu only). Check here for details, and check the banner on their website home page or Facebook page for the GO or NO-GO decision around 5 pm each day.

At 7:30 pm on Wednesday, September 20, the RASC Toronto Centre will livestream their free monthly Speaker’s Night Meeting. The speaker will be Prof. John E. Moores, York Research Chair in Space Exploration, Department of Earth and Space Science and Engineering & Science Advisor to the President – Canadian Space Agency. His topic will be The Adventure of Space Science and Exploration: A Canadian Perspective. Check here for details and watch the presentation at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live.

Eastern GTA sky watchers are invited to join the RASC Toronto Centre and Durham Skies for solar observing and stargazing at the edge of Lake Ontario in Millennium Square in Pickering on Friday evening, September 22, starting at 6 pm. Details are here. Before heading out, check the RASCTC home page for a Go/No-Go call – in case it’s too cloudy to observe.

Spend an afternoon in the other dome at the David Dunlap Observatory! On Saturday afternoon, September 23, visitors 6 years old and up can join me in my Starlab Digital Planetarium for an interactive journey through the Universe at DDO. We’ll tour the night sky and see close-up views of galaxies, nebulas, and star clusters, view our Solar System’s planets and alien exo-planets, land on the moon, Mars – or the Sun, travel home to Earth from the edge of the Universe, hear indigenous starlore, and watch immersive fulldome movies! Ask me your burning questions, and see the answers in a planetarium setting – or sit back and soak it all in. Please note that all guests will sit on a clean floor. A registered adult must accompany all registered participants under the age of 16. We run a session at 1 pm and another at 2:45 pm. More information and the registration links are here.

On Saturday, September 23 from 9:30 to 11:30 pm EDT, the in-person DDO Astronomy Speakers Night program will feature Conor Hayes, a PhD candidate in Physics and Astronomy at York University in Toronto. He will speak on Curiosity’s Got its Head in the Clouds: Eleven Years of Cloud Observations from Gale Crater, Mars.After the presentation, participants will tour the observatory and see a demonstration of the 74” telescope pointed to an interesting celestial object for the visitors to view (weather permitting). More information is here and the registration link is at ActiveRH.

On Sunday afternoon, September 24 from 12:30 to 1 pm EDT, head to the David Dunlap Observatory for in-person DDO Sunday Sungazing. Safely observe the sun with RASC Toronto astronomers! During the session, which is for ages 7 and up, a DDO Astronomer will answer your questions about our closest star – the sun! Registrants will be given an eclipse viewer, learn how the sun works and how it affects our home planet, view the sun through solar telescopes, weather permitting, and visit the giant 74” telescope. More information is here and the registration link is here.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!