Spots on Jupiter, the Demon Dims, a Moon Renewed Deals Dark Skies, See Cygnus’ Delights, and Interplanetary Dust at Dawn!

The autumn Zodiacal Light (at centre left) tilts upwards to the right in this image of it captured by Stu McNair of Richmond Hill, Ontario in October, 2018.

Hello, End-of-Summer Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of September 13th, 2020 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together!

The moon will slide past the sun late this week, leaving evenings all around the world nice and dark for seeing the sights. Taking advantage of that, I’ve prepared a tour of Cygnus the Swan for you. Meanwhile, Jupiter and Saturn – and later, Mars – still beg for views in the evening sky – with Jupiter hosting several shadow transit events this week. Venus gleams in the east before dawn, which will also show you the zodiacal light – if your skies are dark enough. Here are your Skylights!

Zodiacal Light

For about half an hour before dawn during the moonless periods in September and October every year, the steep morning ecliptic favors the appearance of the zodiacal light in the eastern sky, for observers in mid-northern latitudes. Zodiacal light is sunlight scattered by interplanetary particles concentrated in the plane of the solar system. It is best seen in areas free of urban light pollution.

Between Wednesday morning and the next full moon (on October 1), look just above the eastern horizon for a broad wedge of faint light centred on the ecliptic, which runs through Venus and the bright star Regulus in Leo (the Lion). Don’t confuse the zodiacal light with the Milky Way, which is positioned further to the southeast.

See the Demon Star Dimmed

Algol, also designated Beta Persei, is among the most accessible variable stars for skywatchers. Its visual brightness dims noticeably for about 10 hours once every 2 days, 20 hours, and 49 minutes because a dim companion star orbiting nearly edge-on to Earth crosses in front of the much brighter main star, reducing the total light output we receive. On Sunday, September 13 at 9:08 pm EDT (or 1:08 GMT on Monday), Algol will reach its minimum brightness of magnitude 3.4. At that time, for observers in the Eastern time zone, the star will sit 12 degrees above the northeastern horizon. Five hours later, at 2:08 am EDT (or 6:08 GMT), Algol will be high in the eastern sky, and will have brightened to its usual magnitude of 2.1.

The Moon

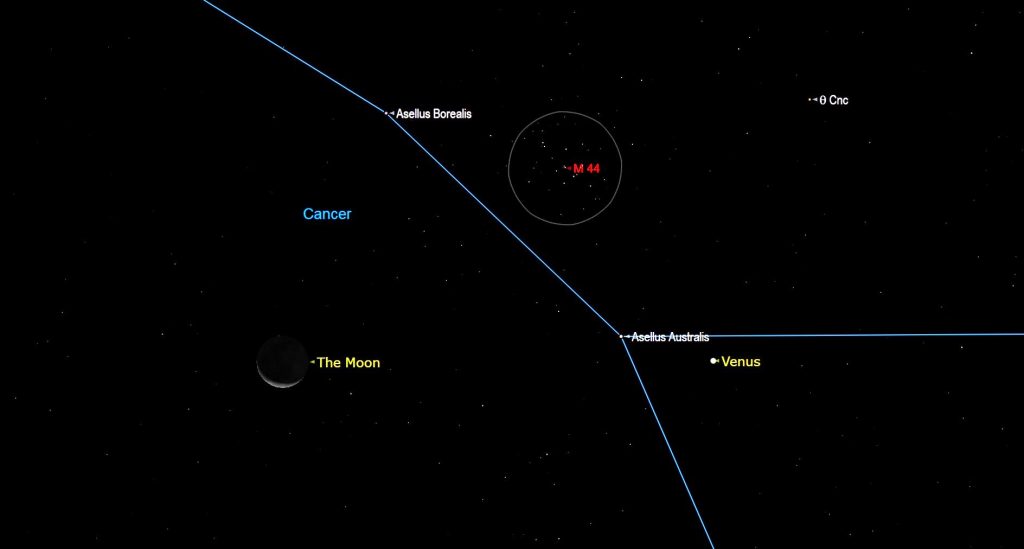

The moon will begin this week as a lovely, thin, waning crescent shining prettily over the eastern horizon before dawn, and then lingering into the daytime sky. On Monday morning, the moon will be positioned a few finger widths to the left (or 4 degrees to the celestial north) of the bright planet Venus. The moon and Venus, which will remain visible in the east until sunrise, will fit together into the field of view of binoculars and will make a lovely wide-field photograph when composed with some interesting landscape. Your binoculars might also reveal the large open star cluster known as the Beehive Cluster or Messier 44, sitting just above and between the moon and Venus in the constellation of Cancer (the Crab). To see the cluster’s stars more easily, hide the moon and bright Venus just below your binoculars’ field of view.

On Tuesday and Wednesday morning, the moon will look even slimmer as it traverses the stars of Leo (the Lion). Wednesday will be the last chance to see the old moon. On Thursday at 7 am Eastern Time (or 11:00 Greenwich Mean Time), the moon will officially reach its new phase. At new, the moon is travelling between Earth and the sun. Since sunlight is only reaching the far side of the moon, and the moon is in the same region of the sky as the sun, the moon will be completely hidden from view for about a day. Since this new moon is occurring a day before perigee, the moon’s minimum distance from Earth, tides will be larger around the world due to the combined tugs of the sun and moon.

After sunset on Friday, September 18, sharp-eyed observers might spot the very slim crescent moon sitting just above the western horizon, and a slim palm’s width to the upper right (or 5° to the celestial north) of Mercury. The moon and Mercury will both fit into the field of view of binoculars – but ensure that the sun has completely disappeared from view before using them.

The slightly more robust crescent moon will be easier to see after sunset on the coming weekend.

The Planets

Speedy little Mercury will continue its visit to in the western post-sunset sky this week – but the low angle of the evening ecliptic will keep it very close to the horizon for everyone living at mid-northern latitudes. If you’re game to look for it, a short viewing window starts a few minutes before 8 pm local time. If you live near the equator, or in the Southern Hemisphere, Mercury will put on a great show for you this month!

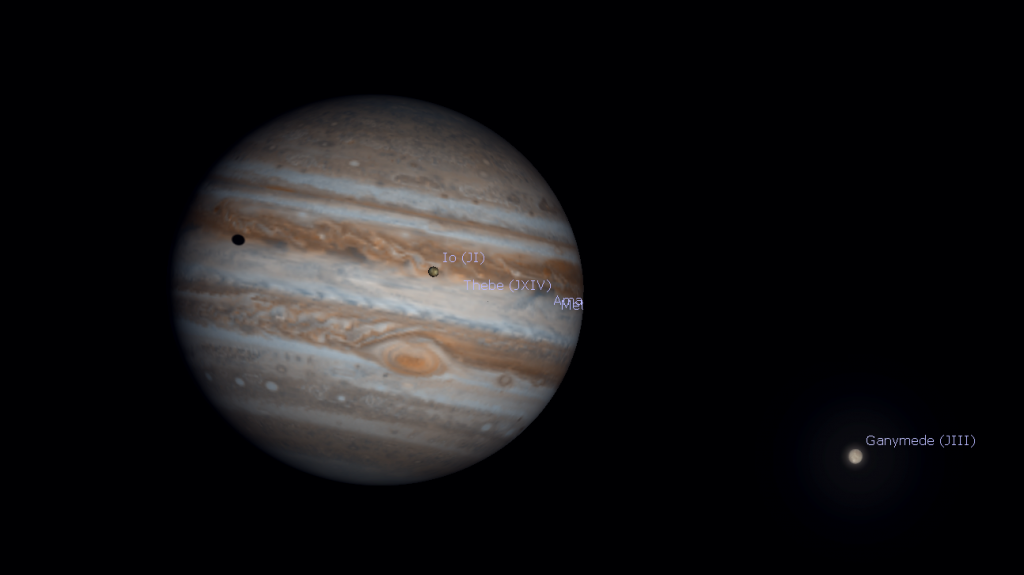

When the sky darkens after sunset, very bright, white Jupiter will pop into view in the lower part of the southern sky. A while after that, dimmer, yellowish Saturn will appear, too – sitting less than a fist’s diameter to Jupiter’s left (east). Good binoculars will reveal Jupiter’s four large Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto as they dance around the planet from night to night. Even a modest-sized telescope will show Jupiter’s brown equatorial belts and the famous Great Red Spot (or GRS, for short) – if the air is steady. Due to Jupiter’s 10-hour period of rotation, the GRS appears every second or third night from any given location on Earth. In the Eastern Time zone, the Great Red Spot will be crossing the planet’s disk after dusk on Tuesday, Thursday, and next Sunday. It will also be visible starting in late evening on Saturday.

From time to time, the round, black shadows cast onto Jupiter by its Galilean moons are visible in amateur telescopes as they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk for a few hours. From 8:47 pm EDT until 11:04 pm EDT on Tuesday evening, Io’s shadow will be traveling across Jupiter. Europa’s shadow will do the same from 10:03 pm to 12:54 am EDT on Friday evening, and Ganymede’s shadow will cross from dusk until 10 pm EDT on Saturday.

Saturn is a spectacular sight in any backyard telescope. Even a small one will show Saturn’s rings. From our vantage point here on Earth, they’ll be narrowing every year – until they vanish for a few weeks during the spring of 2025. Unfortunately, that event will happen while Saturn is close to the sun – so we’ll have to settle for seeing them as a very thin line. In a telescope, the rings are almost as almost as wide as Jupiter’s disk. See if you can see the Cassini Division. It’s the narrow, dark gap that separates Saturn’s main inner ring from its outer one.

A small telescope will also show several of Saturn’s moons – especially its largest, brightest moon, Titan! Because Saturn’s axis of rotation is tipped about 27° from vertical (a bit more than Earth’s axis), we are seeing the top surface of its rings – and its moons can arrange themselves above, below, or to either side of the planet. During evening this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the right of Saturn tonight (Sunday) to the left of the planet next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope might flip the view around.)

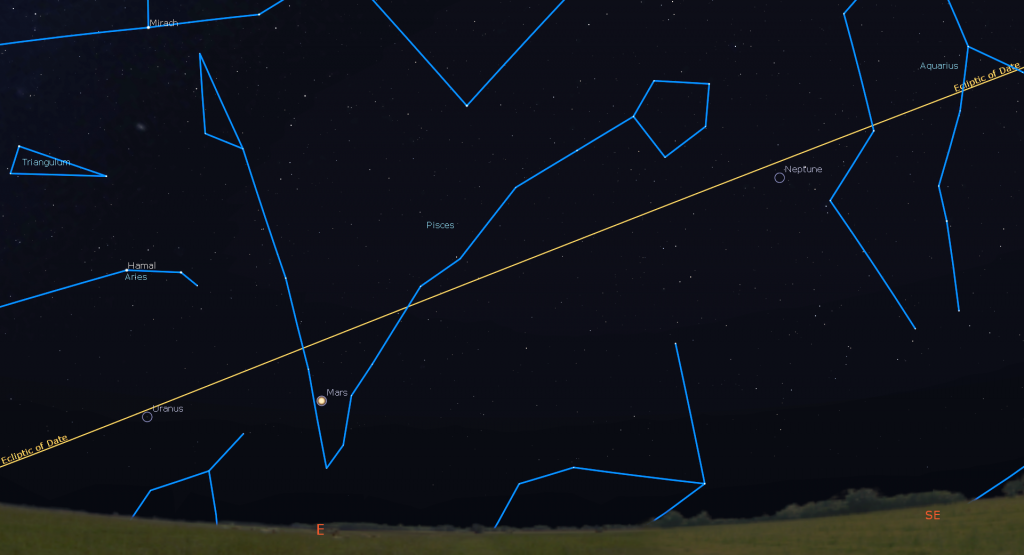

Reddish Mars is steadily increasing in disk size and brightness. The Earth-Mars distance will diminish until October 6. Try to see Mars’ lighter and darker patches, and its bright southern polar cap, in your telescope. This week, the Red Planet will be rising in the east before 9 pm in your local time zone. Then it will cross the sky until dawn, when it will be positioned about four fist diameters above the southwestern horizon. Nothing in the southern sky is as bright, nor as red! Mars is moving retrograde now, causing the planet to temporarily appear to travel backwards compared to the stars beyond it. This week, Mars will sit within the narrow “V” of modest stars at the bottom of the constellation of Pisces (the Fishes). Check it out!

This week’s moonless sky will be ideal for looking for the Ice Giant planets. Blue-green Uranus will rise among the stars of southern Aries (the Ram) at about 9 pm local time and will sit a generous fist’s diameter to the lower left (or 13° to the celestial east) of much brighter Mars.

Neptune is located among the stars of northeastern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), about two degrees to the left (or celestial east) of the medium-bright star Phi Aquarii or (φ) Aqr. This week, Neptune will already be in the lower southeastern sky after dusk. Then it will climb higher until about 1 am local time, when you’ll get your clearest view of it while it’s halfway up the southern sky.

Last Friday, Neptune was directly opposite the sun in the sky. During the week surrounding opposition, Neptune is closest to us for this year – 4 light-hours or 28.9 Astronomical Units from Earth. (One Astronomical Unit is the average Earth-Sun distance.) Neptune is at its peak magnitude of 7.8, and will be visible all night long in good binoculars and backyard telescopes in a dark sky. Around opposition, Neptune’s disk size grows slightly to 2.4 arc-seconds.

Extremely bright Venus will rise in the east-northeast at about 3:15 am local time this week, and then remain visible until sunrise as it is carried higher in the eastern sky by the rotation of the Earth. Viewed in a backyard telescope, Venus will show a gibbous, half-illuminated shape. The planet will be traveling eastward through the modest stars of Cancer (the Crab). On Monday morning, the bright planet will sit a few finger widths to the lower right (or 2.5 degrees to the celestial south) of the big open star cluster in central Cancer known as Messier 44 or the Beehive Cluster – with the lovely waning crescent moon close by.

Venus is shifting towards the sun – but the later sunrises at this time of year will let it shine in a dark, pre-dawn sky until early December! And while you’re up early, enjoy a view of the extremely bright star Sirius, and Orion (the Hunter) sitting well off to Venus’ right.

A Tour of Cygnus the Swan

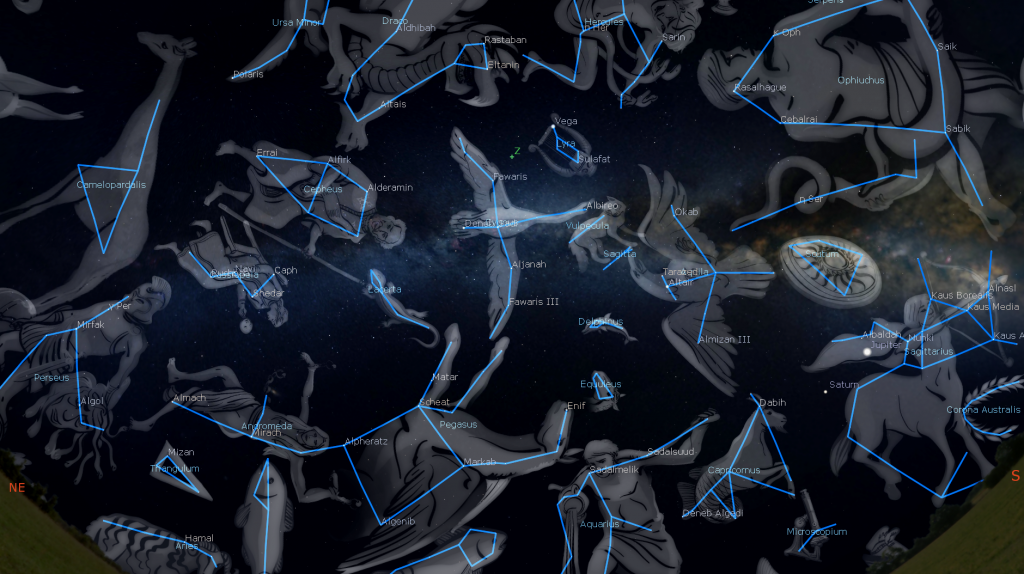

With the moon missing from evening skies, darkness falling earlier, and evening temperatures still mild, this is an ideal week to get out under the stars. Objects in the sky directly overhead will always appear at their best because you are seeing them through the least amount of intervening air. In early evening during mid-September every year, the constellations of Lyra (the Harp), Cygnus (the Swan), and Draco (the Dragon) surround the zenith. I’ll post a sky chart of the area here. We toured the stars of Lyra in my Skylights from August 25 archived here, and highlighted some of the objects you can look at with binoculars and small telescopes. This time we’ll dive into Cygnus!

Head outside on the next clear evening, face east, and look nearly overhead for the very bright star Vega. Below it is the realm of the great constellation Cygnus (the Swan). Its brightest stars also form the asterism called the Northern Cross. In size, Cygnus is the 16th largest of the 88 official constellations. By using your closed fist held at arm’s length, you can see that the bright stars of the swan span more than two fists (or 22°) head to tail, and nearly four fists (or 36°) across the wingspan. Its official boundary includes a large northwestern section that is devoid of bright stars, but loaded with rich nebulas and star fields.

Cygnus sits entirely north of the celestial equator, making it widely visible around the world. Some of its more northerly stars are circumpolar for observers in mid-northern latitudes around the world – that is, they never drop below the horizon.

This constellation is one of the few that truly resembles the name. In Greek mythology Cygnus was Zeus, disguised as a beautiful swan to seduce Leda, the mother of Helen of Troy. Cygnus was also said to represent mourning Orpheus. His harp is nearby, in the form of Lyra. The Arabs envisaged the stars of Cygnus as a hen. The Dakota people of North America saw a salamander, the Ojibwa people imagined a crane, and the Mongolians a bow and arrow. Ancient Chinese astronomers used a different grouping of stars and formed a bridge crossing the river of the Milky Way.

When facing east, the swan is flying upwards toward the right. Starting at Vega, shift your gaze 2.3 fist diameters down and slightly to the left (or 23° or to the celestial east) to the bright, blue-white star Deneb, which marks the tail of the swan. (The word means “tail” in Arabic.) At magnitude 1.25, Deneb is several times dimmer than Vega’s 0.0. Deneb is a whopping 2,550 light-years away from our solar system. It shines as brightly as it does because this luminous, supergiant star emits many tens of thousands of times more visible light than our Sun. The slow wobble, or precession, of the Earth’s rotation axis will cause Deneb to replace Polaris as the North Pole Star around the year 9,800. The last time it did so was around 16,000 BCE.

Sadr is the prominent star located about a palm’s width to the upper right (or 6° to the celestial southwest) of Deneb. It marks the centre of the swan’s body (and the giant cross). The name is derived from an Arabic expression for “the hen’s breast”. Even though it’s somewhat closer to us (1,800 light-years) than Deneb, Sadr shines about 2.5 times fainter than Deneb. It’s also somewhat cooler than Deneb, giving it a warmer colour.

The swan’s head is marked by a visible, but much dimmer star named Albireo. That star sits approximately 1.6 fist widths to the upper right (or 16° to the celestial southwest) of Sadr – swans have long necks! Albireo is also parked close to the centre of the Summer Triangle. Albireo is a favorite of summer star parties because it divides into a coloured double star when viewed in a small telescope. The two stars show a lovely sapphire (blue) and topaz (yellow) in colour – because they are burning at 11,000 degrees and 4,400 degrees respectively.

Measurements from the Gaia space telescope indicate that Albireo is likely only a line-of-sight double – a happenstance of geometry. The brighter yellow star sits 328 light-years away from us, and the dimmer blue star is 389 light-years away. They’re close enough to one another to be gravitationally bound together – but Gaia found that they are travelling in much different directions – uncommon in stellar siblings. Albireo was given its single name before telescopes were invented and revealed that it was actually a duo. Its alternate designation is Beta1,2 Cygni – where the numerals refer to each partner.

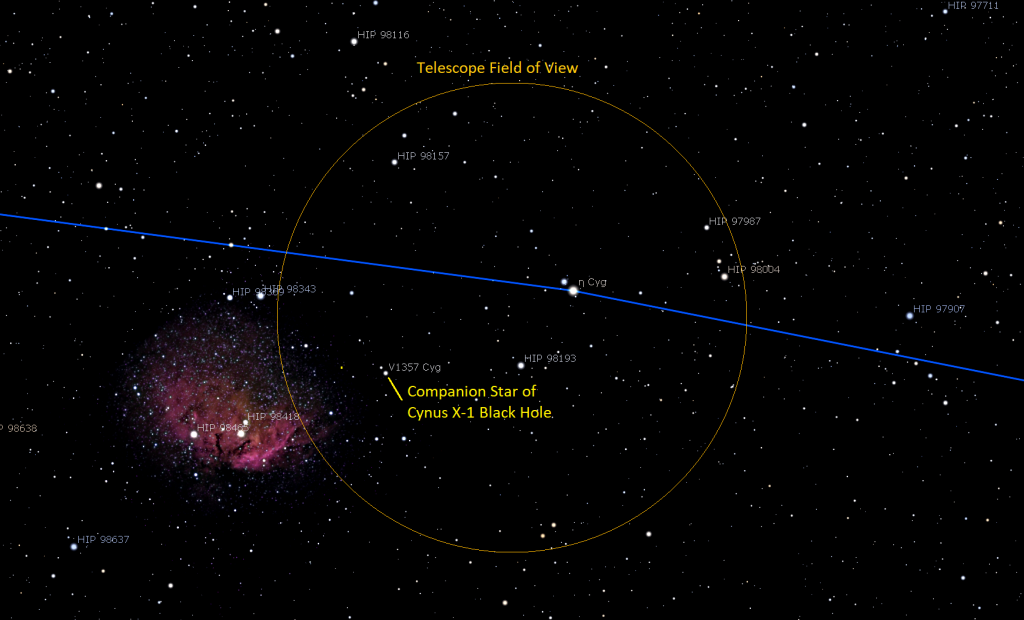

See if you can spot a medium-bright star positioned about midway along the swan’s long neck, between Sadr and Albireo. That’s Eta Cygni or (η) Cyg, a warm-tinted star located about 135 light-years from Earth. This aging star has started to fuse Helium in its core. Binoculars might reveal a magnitude 8.8, blue-white star sitting 26 arc-minutes (a full moon’s diameter) to the lower left (or celestial east) of Eta. Named HD 226868 and V1357 Cygni, this hot, O-class star is emitting copious amounts of X-ray radiation. In 1971, astronomer Tom Bolton of the University of Toronto used the 74” telescope at the David Dunlap Observatory in Richmond Hill, Ontario to analyze the light from that star. He determined that something dark and massive was tugging it around. That invisible object came to be known as Cygnus X-1, the first confirmed black hole! The Canadian rock band Rush wrote a song about it!

With Deneb, Sadr, Eta Cygni, and Albireo running tail to head, you should now be able to locate a long, crooked chain of slightly dimmer stars running from lower left to upper right – forming the swan’s broad wings. Each wing extends about two fist diameters from Sadr and contains three stars. Let’s tour the wings.

Moving less than a fist’s width above (or 8° to the celestial northwest) from Sadr, we first arrive at Al Fawaris (“the Riders”) also known as Delta Cygni or (δ) Cyg. The star has also been called Rukh, after the giant bird The Roc in Middle Eastern mythology (and some sword and sandal movies). Decent telescopes at high magnifications should be able to split that star into a pair of greenish-blue and yellow-white stars. Al Fawaris will also one day become Earth’s pole star.

A further jump of 7° to the upper left lands us at white Iota Cygni or (i) Cyg. A couple of finger widths beyond Iota sits yellowish Kappa Cygni or (κ) Cyg, the wingtip star. Kappa is an aging G-type star (like our sun) – buts it has swelled to almost ten times the size of the sun. Both Iota and Kappa sit about 120 light-years away from us.

Let’s trace out the lower wing. Moving about 8° downwards from Sadr we find the bright, yellow-orange star Aljanah or Gienah, both names originate from the Arabic expression for “Wing of the Swan”. Also known as Epsilon Cygni or (ε) Cyg, Gienah is an old star, located 72 light-years away from us, that is beginning its death process.

A palm’s width below Gienah you should spot a medium-bright, yellow-orange star named Zeta Cygni or (ζ) Cyg. A little more bending to the left and another palm’s width lower is the tightly separated double star Mu Cygni or (μ) Cyg. This pair of stars is orbiting one another with a period of about 790 years. And because their orbit is nearly edge on to us, they slowly move closer together and draw farther apart over the decades. Right now they are separating.

If you can leave the light polluted skies of the city, look for some of Cygnus’ wonderful nebulae – clouds of gas and dust that glow in pinks and blues – lit from within by the radiation emitted by the stars they contain. These large objects are best seen with binoculars, and sometimes your unaided eyes, under very dark, moonless skies. Check them out! A few finger widths below Deneb is the North American Nebula, named for its distinctive shape. It’s quite easy to see as a faint, bright patch in binoculars. It’s more than three times larger than a full moon. The Pelican Nebula, a smaller patch to its upper right, is part of the same gas cloud – but separated from the other piece by dark foreground dust.

A faint gas cloud region called the Gamma Cygni Nebula surrounds Sadr. This nebula, which is nearly 5,000 light-years away from us, measures six full Moon widths across! Sadr is not related to the nebula, though – the star is only half as far away as the nebula. Before moving on, look for an extra-dark patch of sky sitting two finger widths below Sadr. The patch, almost a fist diameter across and several finger widths tall is more dark dust that is blocking the stars of the Milky Way beyond it. The patch is also known as the Northern Coalsack. (A larger, darker coalsack is visible from the southern hemisphere.)

The large, delicate, and pink Veil Nebula or Cygnus Loop sits about three finger widths to the lower right of Gienah. Its roughly circular shape, five full Moon diameters across, is the tattered remnant shell of a supernova that occurred five to eight thousand years ago. A particularly strong section of the nebula sweeps across a foreground star named 52 Cygni. That star sits a few finger widths to the lower right of Epsilon Cygni. Put your lowest magnification eyepiece in your telescope, point it at 52 Cygni, and then look for a narrow slash of dim light crossing the field of view through the star.

Telescope owners should look for the Blinking Planetary. It’s a stellar corpse (like Lyra’s Ring Nebula) that plays an optical illusion on you. When you look straight at it, its central white dwarf shines as a tiny pinprick. But use averted vision, and the blue halo pops into view. You can make the two views flip back and forth. It’s fun! The object is located about two finger widths to the lower left of the line joining Fawaris and Iota Cygni (in the upper wing) – a bit closer to Iota.

If you are viewing the sky in a dark location, you should see that the band of the Milky Way runs directly through Cygnus – as if she is about to land for a swim! The rich star fields surrounding the constellation are terrific for laying back and scanning with binoculars. You might find one of the many open star clusters in Cygnus, such as the Cooling Tower Cluster (Messier 29), which is located less than two finger widths to the lower right of Sadr, two more bright clusters along the neck below Eta Cygni, the bright cluster Messier 39 located a fist’s diameter to the lower left of Deneb, and several clusters surrounding Delta Cygni.

Let me know how your exploration of Cygnus goes.

Cepheus the King

If you missed last week’s in-depth tour of the circumpolar constellation of Cepheus (the King), I posted it here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory Youtube channel, where they offer free online viewing through their rooftop telescopes, including their new 1-metre telescope! Details are here.

On Wednesday evening, September 16 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will live stream their monthly Recreational Astronomy Night Meeting at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live. Talks include the Sky This Month (presented by me), and talks about astro-imaging, a kid’s perspective on observing programs, and astronomy books. Details are here.

My Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National will return on Tuesday, September 22, when we’ll cover telescopes for beginners – how to set them up and use them most effectively. Details and the schedule are here. In the meantime, join Jenna and John Reid on alternate Thursdays at 3:30 pm EDT as they run through the RASC’s Explore the Universe certificate.

The Canadian organization Discover the Universe is offering astronomy broadcasts via their website here, and their YouTube channel here.

On many evenings, the University of Toronto’s Dunlap Institute is delivering live broadcasts. The streams can be watched live, or later on their YouTube channel here.

The Perimeter Institute in Waterloo, Ontario has a library of videos from their past public lectures. Their Lectures on Demand page is here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!