Sunset Timing, the Morning Moon Launches Hanukkah and Poses with Virgo Stars and Venus, and December Dark-Sky Delights Include Two Comets!

This is a portrait of the two groups of half-sisters related in mythology as daughters of Atlas: the Hyades, at left, and the blue Pleiades, at right, two nearby open star clusters in Taurus, imaged by Alan Dyer from Quailway Cottage in southwest Arizona, December 15, 2017. The bright, orange star at far left is Aldebaran, the eye of Taurus. This area of the sky is filled with dust which colours the sky in shades of brown and blue. See more of Alan’s work at https://amazingsky.smugmug.com/.

Hello, Early-December Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of December 3rd, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

Then moon will move into the post-midnight sky this week worldwide, where it will pass some bright and interesting stars in Virgo before posing prettily with Venus before sunrise. The moonless evenings will allow us to view the Pleiades, some other December deep sky treats, and a couple of comets. I also review when sunrise and sunset are, make the connection between Hanukkah and the moon, how Mercury dances around the sun, and I highlight the rest of the planets doings. Read on for your Skylights!

“Sunrise! Sunset!”

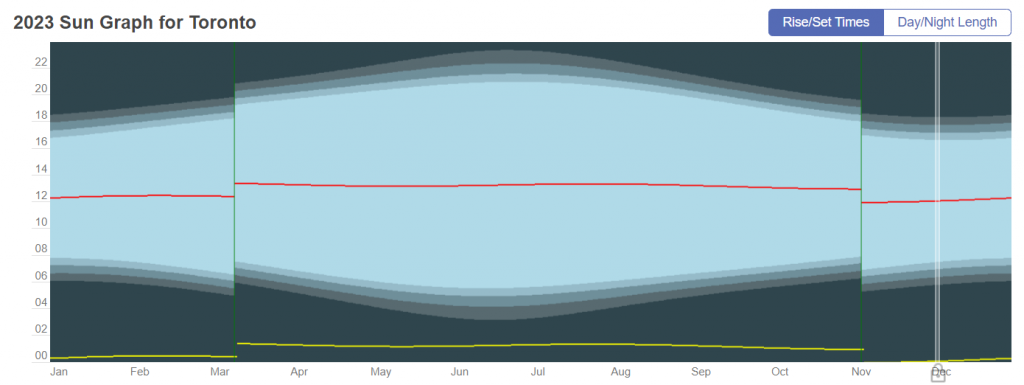

Are you one who dislikes the early sunsets of winter? Well, fear not, as the worst is behind you! This coming weekend, for latitudes near Toronto, the sun will set at 4:40 pm local time – the earliest for the year. Starting next week the sun will set later by about a minute per week. The amount of daylight hours will still shrink, though, because sunrise will continue to arrive later until the first few days of January. The difference occurs because the slope of the ecliptic where it meets the western horizon at sunset is steeper than where it meets the eastern horizon at sunrise, affecting when the last bits of the sun’s disk cross the horizon line. That variation depends on your latitude on Earth. At the equator, the ecliptic is nearly vertical at both ends of the day.

Hanukkah and the Jewish Calendar

Astronomy is a secular science, but there is plenty of astronomy embedded within religious and cultural traditions whose adherents have gazed upon the heavens since antiquity. Let’s look at Hanukkah (or Chanukah, meaning “dedication/consecration/housewarming”, which begins at sundown on Thursday, December 7.

Most cultures around the world have designed their calendars around the cycles of the moon and the sun’s altering position in the daytime sky and its apparent passage through the stars. The Jewish lunisolar calendar (and others) uses the first glimpse of the young, crescent moon to mark the beginning of a month. But the moon’s phases repeat every 29.5 days, so that missing half-day needs to be factored in. The Jewish calendar makes some months only 29 days in length – the chaser “missing” months – and other months 30 days in length – the malei, “full” months.

To account for the ten-day difference between the length of the solar year and twelve 29.5-day lunar months, and to ensure that the calendar of Jewish observances remains synchronized with the seasons, a leap-month is added every two or three years on a repeating 19-year Metonic cycle. On those years, the springtime month of Adar is observed twice consecutively.

Nissan, the first month in the Jewish calendar, begins with the new moon following the March Equinox. But the Jewish New Year, which is said to honour the anniversary of the creation of Adam and Eve, occurs on the first day of the seventh month, which is named Tishrei. That month always falls in September-October on our western Gregorian calendar.

The month of Tishrei hosts the Jewish High Holidays – Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, plus the significant days of Sukkot, Shimini Atzeret, and Simchas Torah. Rosh Hashanah, which marks Jewish New Year, falls on Tishrei 1. Yom Kippur “day of atonement” falls on the tenth day of the seventh month.

Hanukkah, or the Festival of Lights, is observed for eight nights and days, starting at sunset on the 25th day of the Hebrew month Kislev, which may occur at any time from late November to late December in the Gregorian calendar. The last new moon was on November 13, so Hanukkah will commence on Thursday, December 7 and end at sundown on Friday, December 15.

Last year’s High Holidays and Hanukkah arrived unusually early. But the leap-month of Adar II that was added in spring, 2023 re-aligned them for this year.

The Jewish, Christian, and Muslim calendars all share similar roots, which is why Passover and Easter, and Christmas and Hanukkah, are often coincident. The Muslim calendar is allowed to drift due to the ten-day lunar month to solar year difference, but it resets every 33 years. The Muslim New Year occurs at the Vernal Equinox – but that’s a story for another time.

Comets Update

A periodic comet named 12P/Pons-Brooks that was forecast to become bright enough for binoculars and perhaps unaided eyes next spring has unexpectedly brightened ahead of schedule in what astronomers call an outburst. The media has dubbed this one the “Devils’ Comet” because the gas has erupted from two spots, forming “horns”. There’s a nice photo here. Periodic comets alternate between the inner and outer solar system every few decades or centuries, never venturing close enough to the sun to be destroyed. The most famous of those is Halley’s Comet or 1P/Halley, the first among that class.

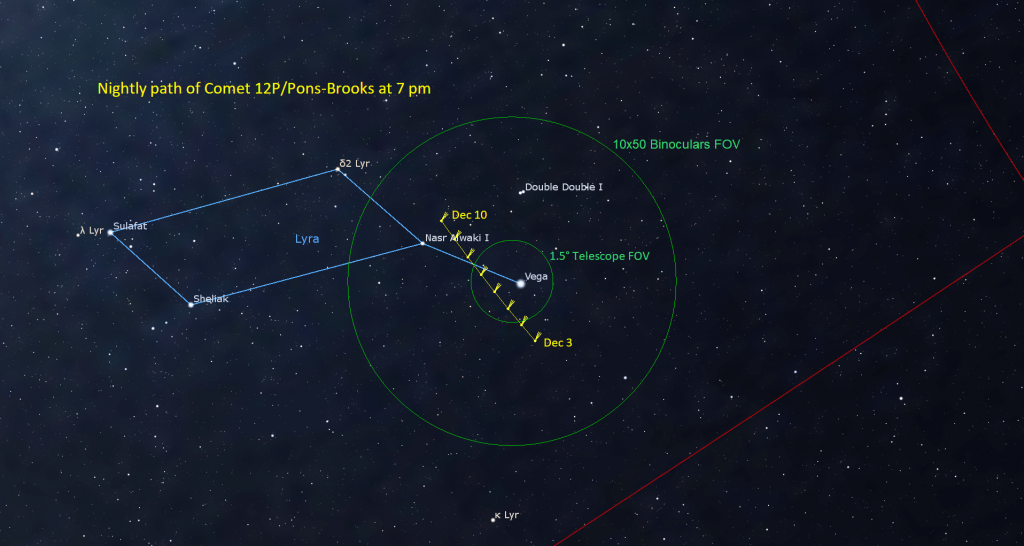

Recent reports are that Pons-Brooks has jumped to around magnitude 8, allowing us to readily see it as a faint, fuzzy smudge in backyard telescopes under this week’s dark skies. Comet Pons-Brooks is very easy to find, too! This week, it will be travelling past the very bright star Vega, which dominates the western sky every evening. Tonight (Sunday) the comet will be located a finger’s width below (or celestial west) of Vega. They’ll be close enough together to share the view in a telescope until Friday, but you’ll want to keep bright Vega tucked out of sight beyond your eyepiece’s field of view. Over the remainder of this week, the comet will slide upwards between Vega and the medium-bright double star Zeta Lyrae, which forms one corner of Lyra’s parallelogram.

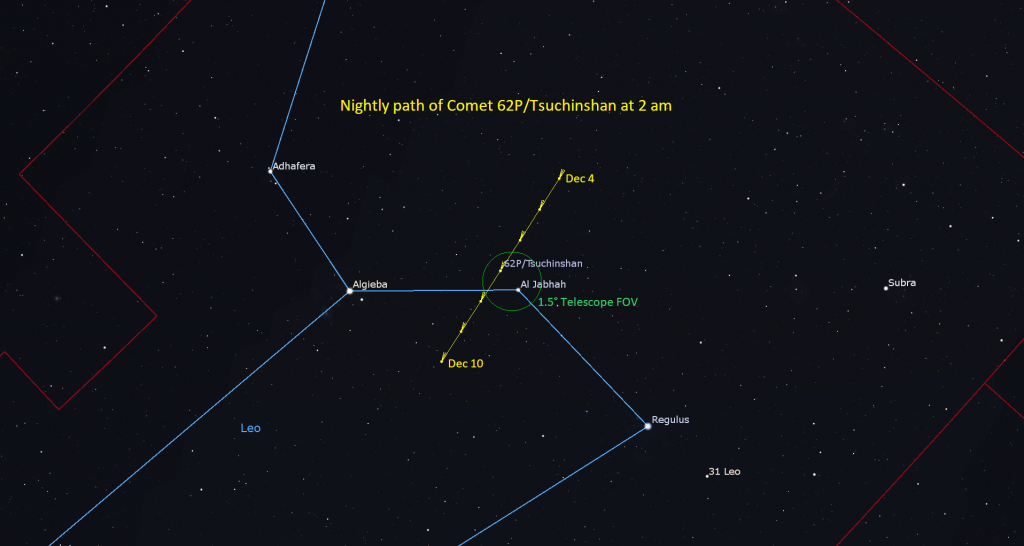

Another magnitude 9.5 periodic comet named 62P/Tsuchinshan is available for viewing in backyard telescopes from the wee hours until dawn. The bright waning moon will be close to the comet on Monday morning, so wait until the moonless mornings in the second half of this week to tackle this one. Like Pons-Brooks, Comet Tsuchinshan will be located close to easily seen stars. It is in Leo (the Lion), passing between Algieba and Al Jabhah (or Eta Leonis) at mid-week. It will be telescope-close to Al Jabhah on Thursday and Friday.

The Moon

If you are lucky enough to have clear skies at night this week, you’ll be able to feast your eyes on the delights of the winter constellations! That’s because the moon will be hanging out in the pre-dawn and morning daytime sky, leaving our evenings dark and moonless.

Tonight (Sunday) Earth’s natural night-light will rise among the stars of Leo (the Lion) before 11 pm local time. Its waning gibbous form will shine near the bright star Regulus until almost sunrise. Then its pale form can be spotted relatively high in the southwestern sky for your trip to work or school. It’ll set around mid-day. Just as any waxing moon in evening looks terrific under magnification, so does the waning pre-dawn moon – if you don’t mind setting the alarm. The sun is setting on the lunar surface at locations along the terminator boundary separating the lit and dark hemispheres, casting long shadows in the opposite direction from what we are used to seeing in evening.

The moon will complete three quarters of its orbit around Earth, measured from the previous new moon, on Tuesday, December 5 at 12:49 am EST or 05:49 Greenwich Mean Time. That will correspond to late evening for observers in western North America. At the third (or last) quarter phase the moon looks half-illuminated, on its western, sunward side because its angle from the sun is approximately 90°. That moon will still be hosted by the stars of Leo from midnight to dawn.

The waning crescent moon will shine prettily in the eastern sky before sunrise for the rest of this week. It will cross through the stars of Virgo (the Maiden) from Wednesday to Saturday, making close visits with her bright, double star Zavijava (or Beta Virginis) on Wednesday, bright and also double Porrima on Thursday, and even brighter Spica on Friday. The big show will be on Saturday morning, when the spectacular sight will be the horns of the crescent moon shining just a few finger widths to the right of brilliant Venus in the southeastern sky. Check the weather forecast and set your alarm if you want to see them after they rise at 4 am local time. No rush, though – they’ll be easy to spot, and photograph, until sunrise around 7:30 am.

If Saturday is cloudy, try again on Sunday morning, when the even thinner crescent moon will shine in Libra (the Scales) beside the bright double star Zubenelgenubi with Venus gleaming above them.

The Planets

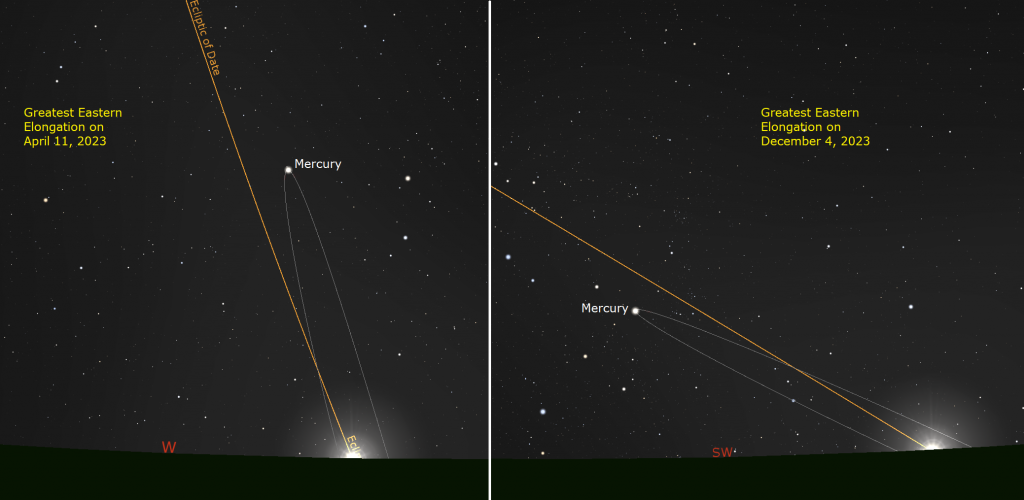

Mercury orbits the sun every 88 days, on its sidereal period, alternating its appearance for us between morning and evening. The planet never extends more than 28 degrees from the sun, and it can be a challenge to see when it isn’t at one of those elongations, which are either east of the sun in the evening sky or west of the sun in the morning sky. The quality of an appearance, even at greatest elongation, varies. Some elongations are a mere 17 degrees. Moreover, Mercury’s orbital inclination of 7° causes it to wander well north and south of the ecliptic, so that even at a wide elongation, Mercury can be underneath a tilted ecliptic, causing it to be held very low in the sky where it is obscured by a thick layer of atmosphere and haze. On any given day, the ecliptic’s slope can be much different for mid-northern and mid-southern latitude observers, so your location controls the quality of the apparition, too.

Since we view Mercury from the moving platform of Earth, Mercury’s appearance intervals alternate between 73 days and 45 days, and its illuminated phase repeats at the sum of those two, or ~116 days, Mercury’s synodic period. For Canadians and other mid-northern latitude observers, March-April evening and September-October morning apparitions are best. Due to Mercury’s orbital eccentricity, some apparitions last longer than others and can be lengthened before or after the date of greatest elongation. The planet also varies a lot in brightness.

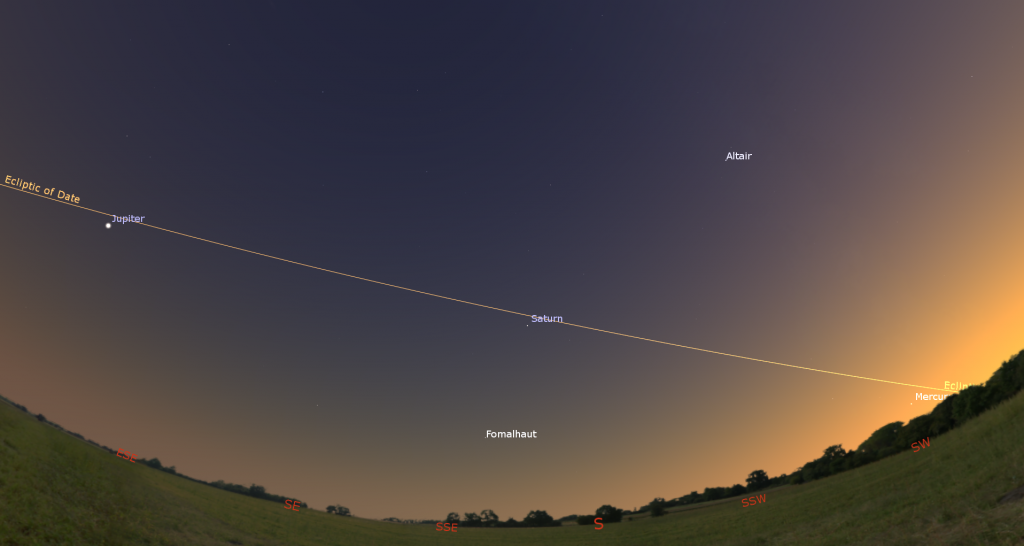

On Monday, December 4, Mercury will reach an elongation 21 degrees east of the Sun and maximum visibility for its current evening apparition. With Mercury positioned well below the tilted evening ecliptic in the southwestern sky, this appearance of the planet will be so-so for Northern Hemisphere observers, but an excellent one for those in the tropics and the Southern Hemisphere. The optimal viewing times at mid-northern latitudes will start around 5 pm local time.

Viewed in a telescope this week the planet will exhibit a waning gibbous phase – but don’t search with binoculars or a telescope until the sun is gone from view. Since Mercury will be returning sunward by moving between us and the sun, it will also be shifting celestial northward, which will lift it toward the ecliptic and improve its visibility for northerners during the rest of this week. In short, Mercury is relatively easy to see. If it’s on your must-see list, stay tuned for future updates. 2024 will bring us several better opportunities to see the speedy planet, including January 12 in the morning, March 24 in evening, and others.

Around the time that Mercury is setting in the southwest, Saturn’s dot will emerge from the evening twilight in the southern sky. Much brighter Jupiter will already be shining at about the same height over in the east. The three planets, plus the now-gone sun, express the great arc of the ecliptic, the plane of our solar system, across the sky. A few minutes later, the three bright stars of the Summer Triangle asterism will appear high in the west.

Saturn will climb to its highest point, due south, around 5:45 pm local time (its best telescope viewing time) and then sink westward to set before 11 pm. The faint stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) will be arrayed to Saturn’s upper left (or celestial east) and the stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) will be off to Saturn’s lower right (or west). Saturn will travel within the bounds of Aquarius until early April, 2025.

Good binoculars can show that Saturn has rings, and any size, style, or brand of telescope will show them well. From Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° is letting us see the top of its ring plane, and allowing its brighter moons to array themselves above, below, and to either side the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the upper lower left of Saturn (or celestial east) tonight to a position farther to the right of the planet (or celestial west) next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) The rest of the moons will be tiny specks. You may be surprised at how many of them you can see through your telescope if you look closely.

The far fainter ice giant planet Neptune has been following Saturn across the sky every night. This week Neptune will be located 2.3 fist diameters to Saturn’s upper left, or 23° to its celestial east-northeast. The diurnal rotation of the sky – the way things tilt as they cross from east to west – will cause Neptune to be lifted increasingly higher than Saturn until Neptune sets at about 1 am local time. On Wednesday, December 6 Neptune will complete a retrograde loop that has been carrying it slowly westward through the stars on the border between Aquarius and Pisces (the Fishes) since July 1. After ceasing its motion tonight, Neptune will ramp up to its regular eastward motion over the coming days. On moonless evenings in December the magnitude 7.9 planet can be observed in good binoculars and backyard telescopes. Place, Lambda Piscium and Kappa Piscium, the lowest two stars of the circlet of Pisces, just outside the top of your binoculars’ field of view and look for blue Neptune near the bottom of the field. Or, search less than a binoculars’ field width to the right (or celestial west) of the box formed by the four medium-bright stars 27, 29, 30, and 33 Piscium.

The bright, giant planet Jupiter is rising in late afternoon now, so it will be very well positioned for viewing from dusk until the wee hours. Jupiter will climb to a position relatively high in the southern sky by 10 pm local time (its peak telescope-viewing time) and then set in the west after 4:30 am. Watch for the two brightest stars of Aries (the Ram) named Hamal and Sheratan, shining a generous fist’s diameter above Jupiter and the Great Square of Pegasus higher and to the right.

Binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons in a line flanking the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. All four moons will be gathered to Jupiter’s right tonight (Sunday).

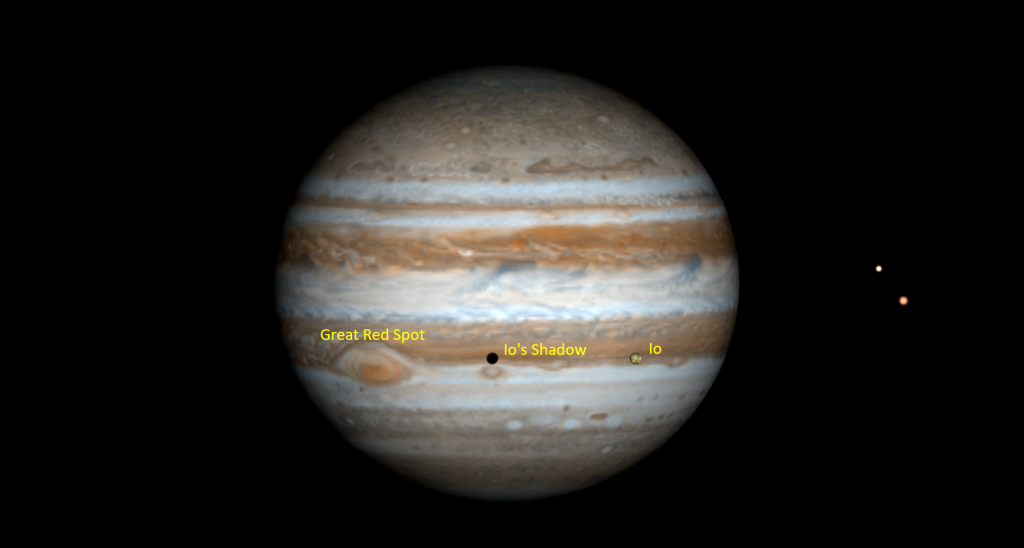

A small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, the GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in mid-evening Eastern Time on Monday, Thursday, and Saturday. It’ll appear late on Wednesday, Friday, and next Sunday night, and also before dawn on Monday, Wednesday, and next Saturday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Tuesday morning, December 5, Io’s small shadow will cross Jupiter from 1:10 am to 3:15 am EST (or 06:10 to 08:15 GMT). Europa’s tiny shadow will cross on Tuesday evening, December 5 from 7:56 pm to 10:13 pm EST (or 00:56 to 03:13 GMT on December 6). Io’s shadow will cross again, this time with the Great Red Spot, on Wednesday evening, December 6 from 7:36 to 9:44 pm EST (or 00:36 to 02:44 GMT on December 7). (These times may vary by a few minutes, and other time zones of the world will have their own crossings.)

The ice giant planet Uranus has been following Jupiter across the night sky, too. This week the speck of the blue-green planet will be positioned 1.3 fist diameters to Jupiter’s lower left (or 13.5° to the celestial east) in eastern Aries. The bright Pleiades star cluster will also be located a fist’s width to Uranus’ left (or 11° to the celestial northeast). At magnitude 5.63, Uranus is normally quite easy to see in binoculars and backyard telescopes – some people have even been able to spot the planet with their unaided eyes. The diurnal rotation of the sky will lift Uranus to the same height as Jupiter around 9:55 pm local time and then higher still later on. The planet will set towards 6 am local time.

If you’re a morning person, be sure to take a look outside before the sky gets too bright on any clear morning to see the brilliant planet Venus blazing in the southeastern sky. If you head out before dawn, you can see the stars of Virgo (the Maiden) shining around our sister planet, particularly Spica. Due to its daily descent sunward, Venus will drop a little lower each morning. At the end of this week, it will be preparing to cross into Libra (the Scales). Viewed through a telescope, our next-door planet will show a waxing gibbous disk spanning 16.4 arc-seconds.

Mars has now entered the eastern morning sky, but we’ll need more than another month before it becomes visible with ease.

Appreciating the Pleiades

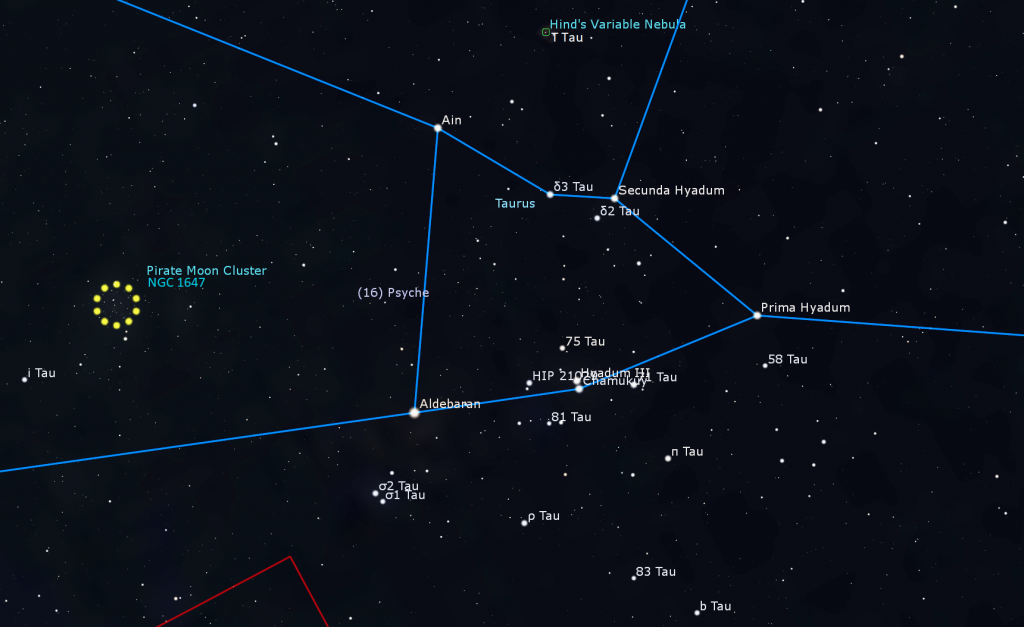

The beautiful open star cluster known as The Pleiades and the Seven Sisters sits about one and a half fist widths above (or 13° to the celestial northwest of) Taurus the bull’s face. The cluster is one of my favorite wintertime objects. It’s also designated Messier 45 (or M45), part of Charles Messier’s famous list of comet-like objects. Look for it climbing the southeastern sky after dusk during December and then high in the southern sky after mid-evening.

The Pleiades is made up of young, hot blue stars. The brightest ones are named Asterope (“A-STER-oh-pee”), Merope, Electra, Maia, Taygeta, Celaeno, and Alcyone. Those “sister” stars are indeed related – born of the same primordial gas cloud. In Greek mythology, they were the daughters of Atlas, and half-sisters of the Hyades, the triangular cluster of stars that make up the bull’s face. Only six of the sister stars are usually seen with unaided eyes – their parents, the stars Atlas and Pleione, are huddled together at the lower (eastern) end of the grouping.

Not surprisingly, many cultures, including Aztec, Maori, Sioux, Hindu, and more, have developed stories around this prominent object that has drawn the attention of humans since antiquity. Many indigenous groups view the Pleiades as the doorway into the afterlife, or the portal through which humans first fell to Earth – naming it the Hole in the Sky. The stars are so important to the Maoris and the related sea-faring groups of the Pacific Ocean, that they have a festival marking its return to the morning sky after disappearing through solar conjunction. In Japan, it is called Subaru, and forms the logo of the eponymous car maker. Due to its similar shape and diminutive size, some people mistake the Pleiades for the Little Dipper.

The Pleiades cluster is located about 450 light years away from the sun, and it makes a wonderful target in binoculars or a telescope at low magnification, where many more siblings are revealed! Galileo was among the first to observe the cluster through a telescope – publishing a sketch made at the eyepiece in 1610. A large telescope under dark skies will also reveal blue nebulosity around the stars – a reflection nebula of scattered starlight from unrelated gas and dust that the stars are passing through. This proper motion will eventually carry the cluster to a position below Orion’s feet! Your backyard telescope can show a neat little triangle of stars huddled beside Alcyone and a tight duo of stars in the centre of the brighter stars’ ring. One of the pair is golden.

December Delights

Last year around this time, I wrote in depth here about the constellation of Perseus (the Hero). Have a look, as its stars will be in nearly the same orientation this week. If you cast your gaze high in the eastern sky in early evening this week, you’ll be struck by Perseus’ brightest star Mirfak shining above the even brighter, yellowish star Capella.

Above and between Perseus and Jupiter sits a trio of medium-bright stars forming the constellation of Triangulum (the Triangle). The triangle is a little too long to fit within your binoculars, but you should be able to view its two left-hand (northeastern) stars together. They are Mizan, the higher brighter star, and Gamma Triangulum to its lower left. Now sweep your binoculars to the lower right to find the tip of the triangle, marked by the prominent star Mothallah.

With Mothallah positioned near the lower left edge of your FOV, look for a faint fuzzy smudge near the opposite side. That’s Messier 33, or the Triangulum Galaxy, a large, nearly face-on, SA-type spiral galaxy located 2.8 million light-years away from us. Under very dark sky conditions, some sharp-eyed observers have been able to see this member of our local galaxy group, making it the farthest object detectable by the unaided human eye. Binoculars and long-exposure images reveal that the galaxy is an oval shape about one finger’s width across, with the long axis approximately north-south.

If you fail to see M33, sweep the binoculars upwards to the right, past the bright star Mirach and then the smaller star Mu Andromedae. Another hop to the upper right will bring you to the much brighter and larger Andromeda Galaxy, or Messier 31.

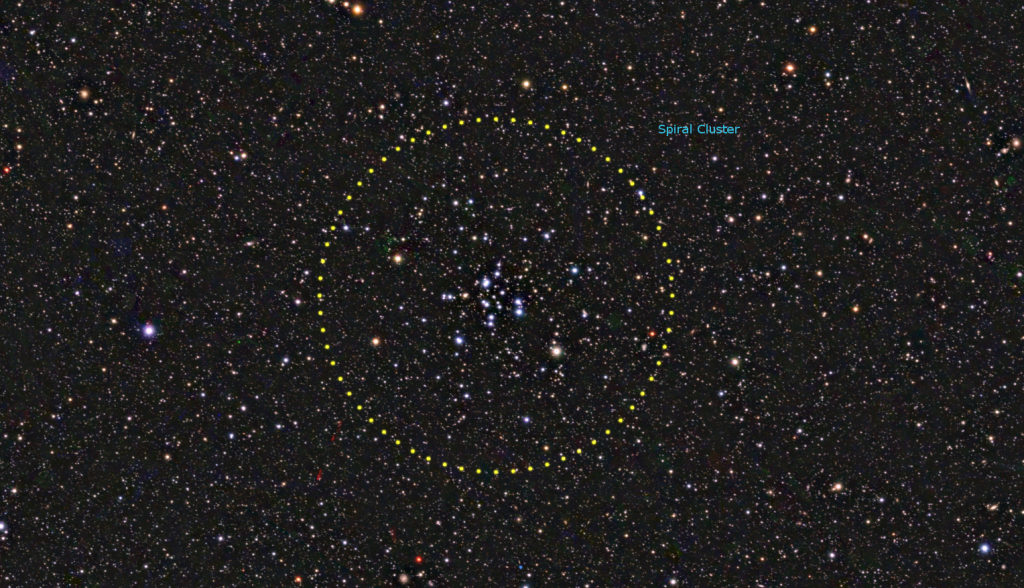

Finally, head back to Mirfak and aim your binoculars or telescope midway between that star and Mizan, and look for the big and bright open star cluster Messier 34, also called the Spiral Cluster and NGC 1039. Many of the cluster’s brightest stars are arranged in curved chains, hence the nickname.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Wednesday evening, December 6 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will host their free, public, in-person monthly Recreational Astronomy Night Meeting in the Gemini East Room at the Ontario Science Centre. The meeting will also be live streamed at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live. Talks include The Sky This Month, a report on last October’s Solar Eclipse, an urban observatory, and more. Details are here.

On Saturday, December 9 from 10 am to noon, you can try out Solar Observing at the Ontario Science Centre! If it’s sunny, members of the RASC Toronto Centre will be setting up outside on the Teluscape in front of the main doors. They’ll have an array of special equipment designed to view the Sun safely. This is free to the public, but parking and admission fees inside the Science Centre will still apply. Check the RASC Toronto Centre website or their Facebook page for the Go or No-Go notification.

Keep your eyes on the skies! I love getting questions and requests. Send me some!