The Bright Moon Touches Taurus’ Horn’s Tip, then Dips a Toe into Earth’s Shadow, while Venus and Mars Shine at Dusk and Dawn!

This wide field image of Orion was captured on January 2, 2020 by Alan Dyer of Alberta, Canada. Orange-tinted Betelgeuse, which marks Orion’s shoulder (top centre), normally shines as bright as Orion’s opposite foot – the bright, blue star Rigel. In the last few weeks, Betelgeuse has diminished noticeably in apparent brightness – a possible precursor to a supernova explosion. This 600 light-years-distant red giant could already have exploded – or, it might not blow up for another 100,00 years. Astronomers don’t know. Alan’s gallery of beautiful astrophotographs is here.

Hello, January Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of January 5th, 2020 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe together!

The bright moon will shine in evening skies the world over this week – and spoil the hunt for leftover Quadrantids meteors and the comet in Perseus. The moon will also brush a horn of Taurus and dip a toe into Earth’s shadow. After sunset, lovely Venus will shine brightly in the western sky, and Mars will tickle the claws of the Scorpion and slide towards its rival in the pre-dawn east. Here are your Skylights!

The January Full Moon and Lunar Eclipses

The moon has always shone down upon humans on Earth. At some point, early people began to seek to understand our natural environment and to take advantage of the annual variations in the seasons to schedule planting, harvesting, hunting, and celebrating life events. The twelve or thirteen full moons per year acted as obvious celestial markers. The full moon’s bright light allowed people to be safely out and about at night; lighting the way of the hunter or traveler before modern conveniences like electric lights, or working the fields for extra hours to get the harvest in. By the way – those extra, thirteenth full moons, which fall into different months each year, are commonly referred to as blue moons.

Each society around the world developed its own set of stories for the moon, and every month’s full moon now has one or more nick-names. The Indigenous Ojibwe people of the Great Lakes region call the January full moon Gichimanidoo Giizis, the “Great Spirit Moon”. For them it signifies a time to honour the silence, and recognize one’s place within all of Great Mystery’s creatures. The Cree of North America call it Opawahcikanasis, the “Frost Exploding Moon”, when trees crackle from the extreme cold temperatures. For Europeans, the January full moon is commonly known as the Wolf Moon, Old Moon, or Moon after Yule. The Wolf Moon term might be derived from North American First Nations traditions, although some think it has an Anglo-Saxon origin. In either case, it’s likely that the hungry wolves calling to one another in the dead of winter left an impression on people before our modern era.

On Friday afternoon, January 10 at 2:21 pm EST (19:21 UT or Greenwich Mean Time), the moon will reach its full moon phase. The moon will still appear full when it rises several hours later. Full moons in January always shine in or near the stars of Gemini (the Twins) or Cancer (the Crab). Since they are, by definition, opposite the sun on this day of the lunar month, full moons are always fully illuminated – rising at sunset and setting at sunrise. Full moons during the winter months at mid-northern latitudes climb as high in the sky as the summer noonday sun, and cast similar shadows.

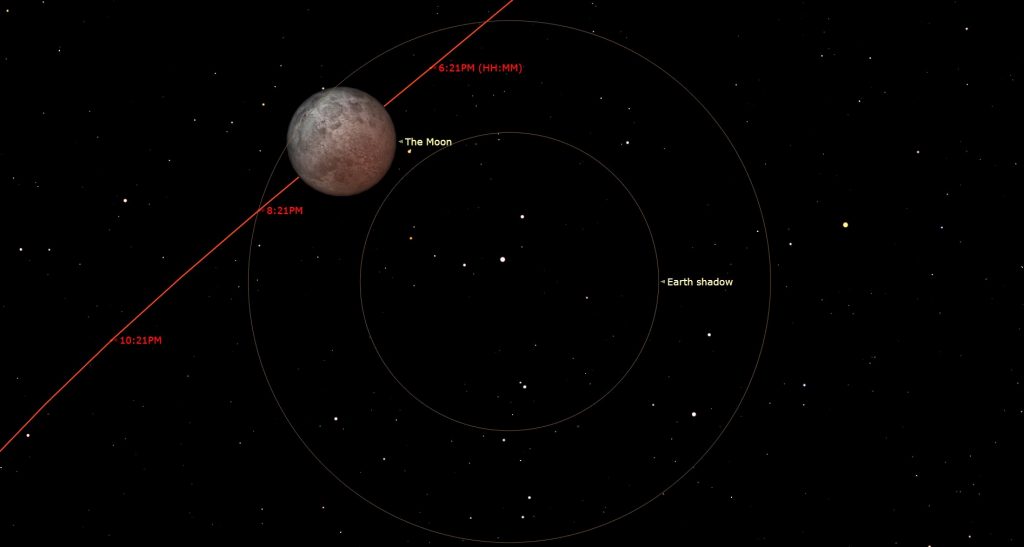

This month’s full moon will also occur while the moon is close to the ecliptic, producing a penumbral lunar eclipse. Here’s why. The spherical Earth casts a circular shadow into space opposite the sun. Because the sun always sits squarely on the ecliptic, the Earth’s shadow spans the ecliptic, too. When the moon, or an artificial satellite (including the space station), passes through that round, invisible shadow, formally known as the umbra, the sun’s light can’t reach them – so they disappear from view while in that patch of sky. (The moon and satellites are only visible because they reflect sunlight down to us.)

Because the sun is such a large sphere, there is a ring around the umbra where some of the sun’s disk is still visible to those objects. They are still lit by sunlight, but less so than usual. That ring is called the penumbra. When the moon passes through the umbra, we see a total lunar eclipse. When the geometry causes the moon to miss the umbra but pass only through the penumbra, we see a penumbral lunar eclipse. As you can imagine, the moon darkens only a little during a penumbral lunar eclipse, and we don’t get the reddened, “blood moon” effect.

Partial lunar eclipses occur when the moon sits fully within the penumbra, but only manages to dip partway into the umbra. Every total lunar eclipse has a partial phase, when the moon transitions into and out of the umbra. Every moment of any type of lunar eclipse is safe to watch without eye protection.

Unlike total solar eclipses, which have a very precise alignment, each lunar eclipse is visible from anywhere on Earth where the moon is above the horizon – generally about half of the globe. Friday’s penumbral lunar eclipse will be visible across Europe, eastern Africa, Indian Ocean, and Asia. In North America, Alaska and the Canadian Maritimes will be treated to only the beginning and final stages of the eclipse, respectively. Western Africa and Australia will also see portions of the eclipse. The rest of us can tune into a live stream. (Search on YouTube for those streams.)

The eclipse will begin when the moon contacts the Earth’s penumbra at 17:07:45 GMT (or 12:07 pm EST on Friday). The moon will enter almost completely into the Earth’s northern penumbral ring, subtly darkening the moon’s southern edge more than its northern edge. However, the effect will be visible only within about 30 minutes on either side of greatest eclipse, which will occur at 19:10:01 GMT (or 2:10 pm EST). The penumbral eclipse will end at 21:12:24 GMT (or 4:12 pm EST). I’ll post a detailed diagram here.

The next lunar eclipse that will be observable across Canada and the USA, another penumbral one, will occur on November 30. Lots of detailed information about eclipses can be found at Fred Espenak’s Eclipsewise.com website.

The Moon and Planets

The moon will dominate evening skies worldwide this week, as it journeys through the middle part of its monthly trip around the sun. Unfortunately, its bright light will largely overwhelm any leftover Quadrantids meteors, Comet PanSTARRS in Perseus (the Hero), and the fainter stars and deep sky objects. Our consolation prize is that the moon looks spectacular in binoculars and telescopes at this phase.

Tonight (Sunday) the waxing gibbous (i.e., more than half illuminated) moon will sit below the stars of Aries (the Ram) – about two finger widths to the left of the circle of dim stars that form the head of Cetus (the Whale, or Sea-Monster). From Monday to Wednesday, the moon will traverse Taurus (the Bull). It will cross directly through the bull’s triangular face before it rises in North America on Tuesday evening, but only observers in Europe and Africa will see the event.

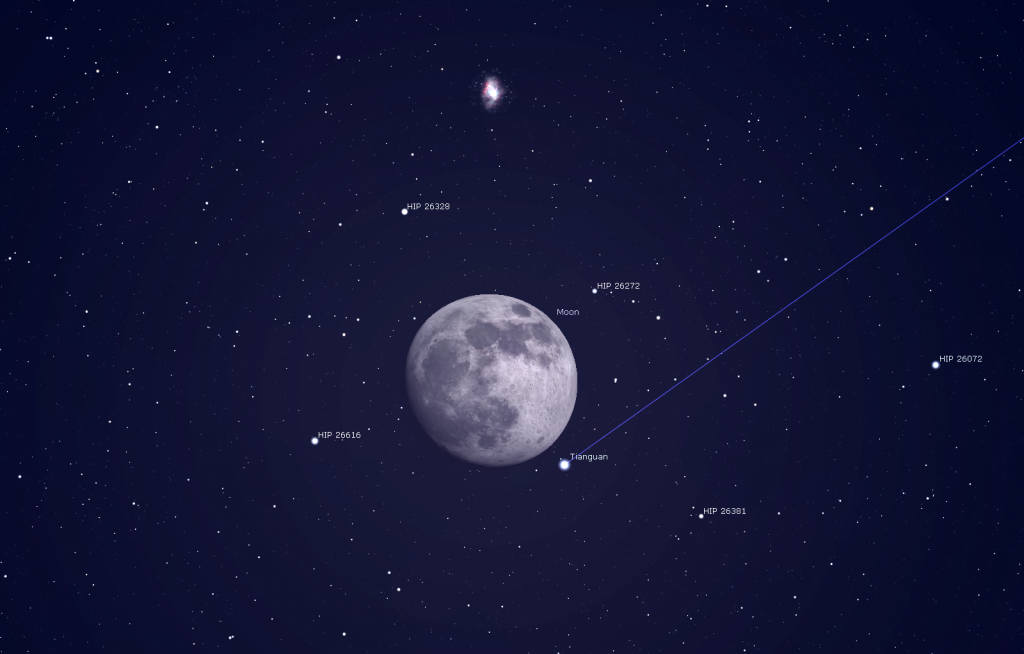

On Wednesday evening, the nearly full moon will pass very closely above a medium-bright star named Tianguan and Zeta (ζ) Tauri, which represents the lower, more southerly horn tip of Taurus. For observers at high northern latitudes, the moon will pass in front of, or occult, that star shortly before 6 pm EST. The pairing will be pretty for the rest of us.

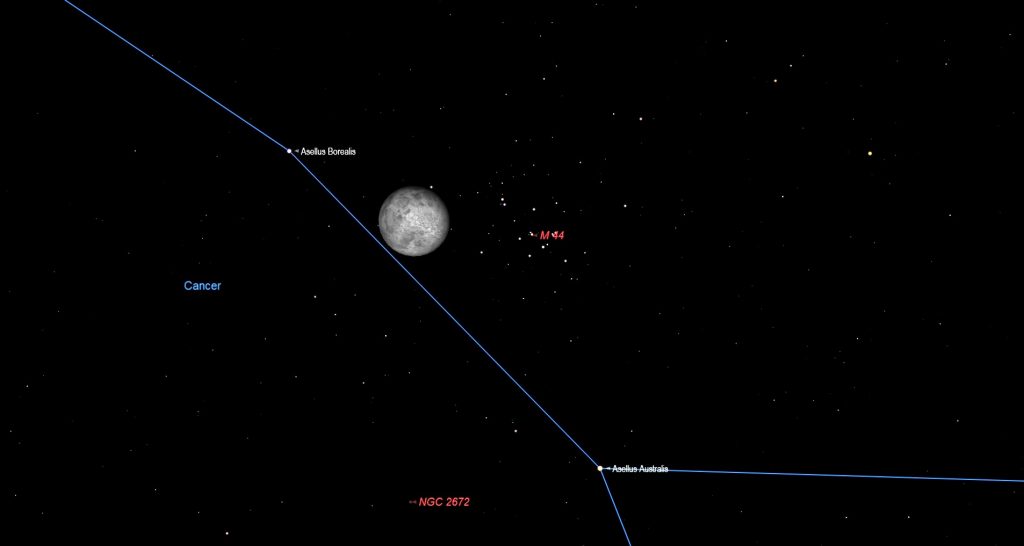

On Thursday and Friday, the bright moon will visit Gemini (the Twins). (I wrote about Friday’s full moon above.) When the now waning gibbous moon rises in the northeastern evening sky on Saturday night, it will be sitting very close to the northern side of the large open star cluster known as the Beehive. The brightest deep sky object in Cancer (the Crab), this cluster is also called Praesepe, which means “manger”, and Messier 44 (or M44). The moon and the cluster will both fit within the field of view of binoculars, although the bright moonlight will obscure the cluster’s dimmer stars. For best results, place the moon just outside of the left edge of your binoculars’ field of view and look for the cluster’s many stars. Finally, next Sunday evening, the moon will start a short trip through Leo (the Lion).

Tonight (Sunday night), take a moment to look for a modestly bright star sitting about three finger widths to the moon’s lower right. That star is named Mu (μ) Ceti, and Al Kaff al Jidhmah. This week the large main belt asteroid designated (4) Vesta will be positioned less than a finger’s width below and to the left of Mu Ceti. Vesta is considerably dimmer than that star, but binoculars and backyard telescopes will reveal the asteroid to you, especially from Monday onwards, when the moon will have hopped away from them.

For planet lovers, our brilliant sister planet Venus will continue its lengthy winter appearance this week – shining very brightly in the southwestern evening sky among the stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) until it sets at about 8 pm local time – by that time, in a dark sky. Viewing Venus in your telescope during the upcoming weeks will reveal that its shape is less than fully round, and it will continue to wane in phase as it swings wider from the sun. Use your telescope on Venus while the planet is higher in the sky, and after the sun has completely set – from 5:30 pm local time. That way, you’ll reduce the blurriness of Venus caused by looking through so much of Earth’s atmosphere.

After easy-to-see Venus, we will have to settle for the harder-to-see ice giant planets Uranus and Neptune. Despite their relatively dim magnitudes and small disk sizes, the delightful colours of those two remote planets make them worthy of a look in backyard telescopes.

This week, distant and dim, blue Neptune will be lost from view well before it sets at about 10 pm local time. You should try to observe Neptune as soon as the sky is dark, when the planet is higher – somewhat less than a third of the way up the southwestern sky. Slow-moving Neptune has been situated among the stars of eastern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), and is positioned a finger’s width to the right (or 1 degree to the celestial west) of a medium-bright star named Phi (φ) Aquarii. I posted a detailed finder chart here.

Both blue Neptune and that golden-coloured star will appear together in the field of view of a backyard telescope at low power. Find Phi Aquarii first and then locate nearby Neptune. Remember that binoculars will display the true relative positions of the objects, but a telescope will flip and/or mirror-image the view. (To find out what your telescope does to the image, see how it changes the view of the moon, and make a note of the result.)

Blue-green Uranus is observable from dusk until just after midnight (it sets at 2 am local time). It is located a generous palm’s width to the upper left (or 7° to the celestial east) of the modest stars that form the V-shaped constellation of Pisces (the Fishes). Uranus is actually within the boundary of Aries (the Ram) – positioned below (or to the celestial south of) that constellation’s brightest stars, Sheratan and Hamal. The planet is also above the ring of stars that form the head of Cetus (the Sea-Monster).

This Saturday, Uranus will temporarily cease its slow motion through Aries – completing a westward retrograde loop that began in early August. After that date, the planet will resume its regular eastward orbital motion. As I discussed for nearby Vesta last week, retrograde loops are produced when Earth passes a solar system object on the faster “inside track” of its orbit around the sun. From our vantage point on Earth, parallax makes the object appear to move backwards for a few months, compared to the distant background stars.

Shining at magnitude 5.7, Uranus is bright enough to see under dark sky conditions with unaided eyes and with binoculars – or through small telescopes under less-dark conditions (but not with this week’s moonlight). To help you find it, I posted a detailed star chart here. If you view Uranus at about 7:30 pm local time, it will be highest in the southern sky – and you’ll be looking through the least amount of Earth’s disturbing atmosphere.

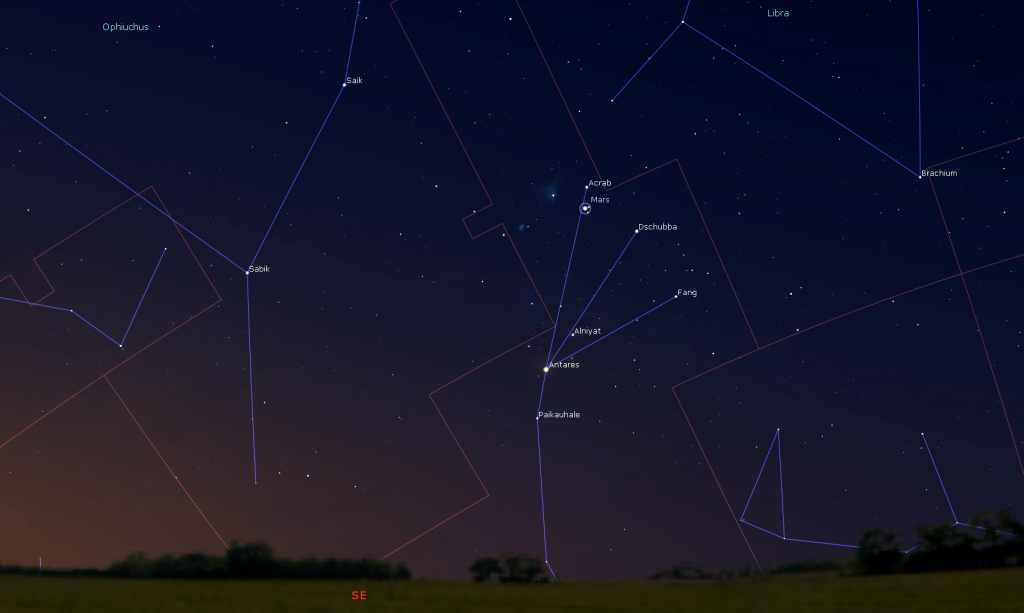

Mars continues to shine in the eastern pre-dawn sky this week (and it will for months to come). The red-tinted planet will be rise at about 4:35 am local time and remain visible until dawn. The relative positions and combined orbital motions of Earth and Mars are causing Mars to appear in roughly the same place in the sky at the same times every morning. However, the planet is moving rapidly eastward through the distant background stars, because they rise four minutes earlier every morning.

This week, Mars will move through the three white claw stars of Scorpius (the Scorpion). At the same time, if you have a low, open southeastern horizon, watch for Mars’ stellar rival, the bright, ruddy star Antares, sitting more than a fist’s diameter below the planet. They’ll have a meeting in two weeks. From now until October, 2020, Mars will continually grow in brightness – and will increase in apparent disk size when viewed in telescopes.

The Bright Stars of January

If you missed last week’s tour and fun facts about the bright stars of January, I posted it with sky charts here. This week will be a great time to head out and find them, since the dimmer stars will be hidden by the bright moonlight.

Binocular Comet Update

A relatively modest comet is traversing the northeastern evening sky this winter – but this week will not be ideal for hunting it. Designated C/2017 T2 (PanSTARRS), the comet is currently shining at magnitude 8.4. That means that it is conveniently positioned for evening viewing in good binoculars or a backyard telescope. I posted a sky chart showing its path over the next month here, and this week’s path below.

The comet is about halfway up the northeastern sky after dusk – and then moves higher in mid-evening as the Earth’s rotation carries the sky east to west. Comets move across the background stars faster than planets wander. This week, the comet will be just inside the northern boundary of Perseus (the Hero). If you face northeast, it will be positioned a palm’s width to the left (or 6 degrees to the celestial north of) the very bright, white star Mirfak in Perseus (the Hero). Over the next seven nights the comet will move a distance of three finger widths of sky, towards the W-shaped constellation of Cassiopeia (the Queen).

Viewed in binoculars and telescopes, Comet PanSTARRS will appear as a dim, fuzzy patch that might exhibit a faint greenish centre. It’s still too early to see a tail, but the comet is expected to brighten much more in the coming months. Stay tuned for updates!

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. On Wednesday nights they offer free public viewing through their rooftop telescopes, including their brand new 1-metre telescope! If it’s cloudy, the astronomers give tours and presentations. Registration and details are here.

If it’s sunny on Saturday morning, January 11 from 10 am to noon, astronomers from the RASC Toronto Centre will be setting up outside the main doors of the Ontario Science Centre for Solar Observing. Come and see the Sun in detail through special equipment designed to view it safely. This is a free event (details here), but parking and admission fees inside the Science Centre will still apply. Check the RASC Toronto Centre website or their Facebook page for the Go or No-Go notification.

This winter, spend a Sunday afternoon in the other dome at the David Dunlap Observatory! On Sunday, February 9, from noon to 4 pm, join me in my Starlab Digital Planetarium for an interactive journey through the Universe at DDO. We’ll tour the night sky and see close-up views of galaxies, nebulas, and star clusters, view our Solar System’s planets and alien exo-planets, land on the moon, Mars – and the Sun, travel home to Earth from the edge of the Universe, hear indigenous starlore, and watch immersive fulldome movies! Ask me your burning questions, and see the answers in a planetarium setting – or sit back and soak it all in. Sessions run continuously between noon and 2 pm, and repeat from 2 to 4 pm. Ticket-holders may arrive any time during the program. The program is suitable for ages 3 and older. The Starlab planetarium is wheelchair accessible, but everyone else sits at floor level. For tickets, please use this link.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests – so, send me some!