The Evening Moon’s Golden Handle, Earth at Aphelion, See Seven Planets Simultaneously, and the Full Moon enters Earth’s Shadow and Joins Jupiter and Saturn!

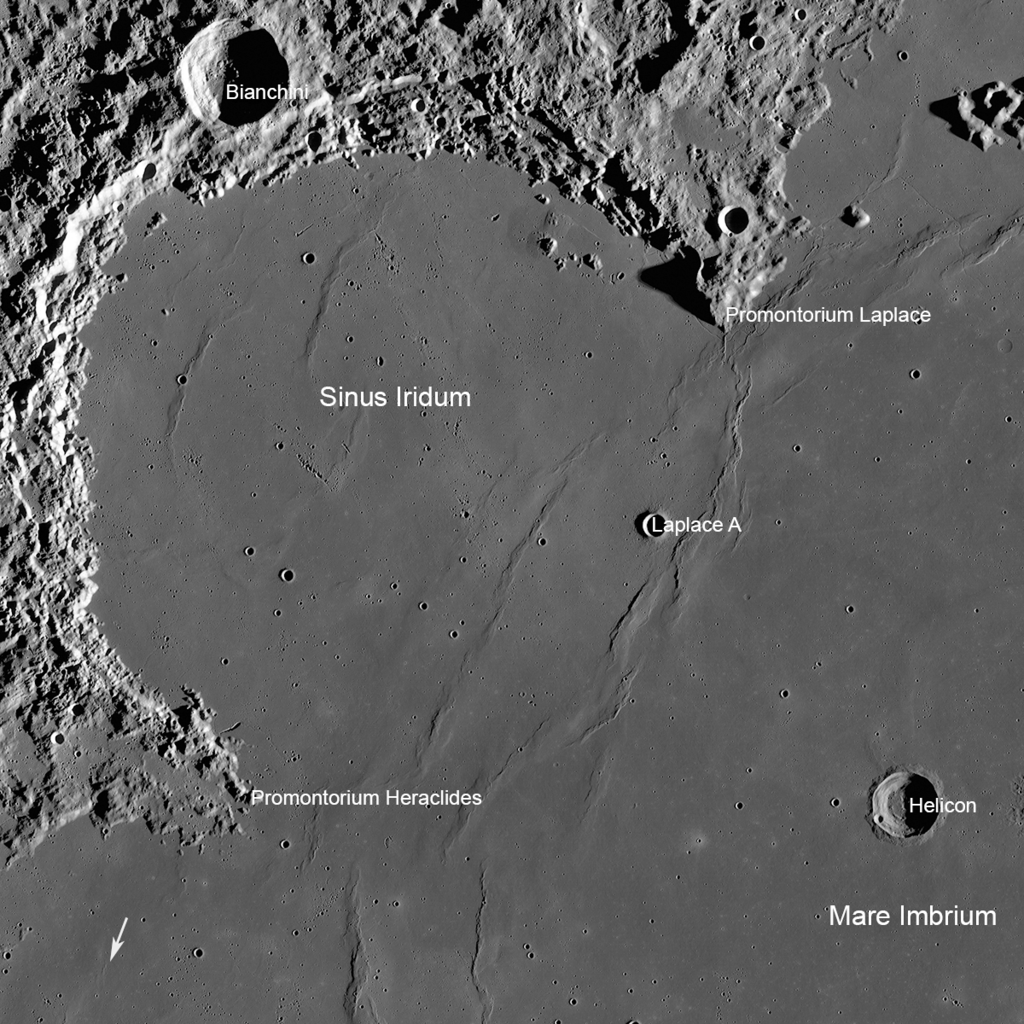

A close-up view of Sinus Iridum and the Golden Handle to its west. The large feature is located in the northwestern (upper left) quadrant of the moon’s disk. The handle effect is visible with sharp, unaided eyes, and through binoculars and backyard telescopes. Note the N-S aligned dorsae, or wrinkle ridges. Image from Wikipedia.

Happy Canada Day, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of June 28th, 2020 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe or the Earth’s interior together!

What a week! The moon will grace the evening skies around the world as it waxes from first quarter to a full moon that will include a partial penumbral eclipse. It will end the week by making a lovely triangle with Jupiter and Saturn. Meanwhile, Jupiter will pass very close to Pluto and deliver a shadow transit/Great Red Spot double feature. Earth will reach aphelion for 2020, and you can observe seven planets, plus Pluto, at the same time in the pre-dawn! Here are your Skylights!

Earth at Aphelion

On Saturday, July 4 at 8 am EDT, or 12:00 Greenwich Mean Time, Earth will reach aphelion, its maximum distance from the sun for this year. The aphelion distance of 152.1 million km is 1.67% farther from the sun than the mean Earth-sun separation of 149,597,870.7 km, which is also defined to be 1 Astronomical Unit (1 AU). Earth’s perihelion (minimum distance from the sun) will occur next January 4. At that time, the Earth will be 147.1 million km from the sun. As you can see, our seasonal temperatures are not produced by our distance from the sun – but by the amount of sunshine we receive in a day – and that is controlled by how much Earth’s axis tilts toward (or away from) the sun.

The Moon

The moon reached its first quarter phase this morning (Sunday) at 4:16 a.m. EDT. At this phase, the relative positions of the Earth, sun, and moon cause us to see the moon half-illuminated – on its eastern (right-hand) side. (The term “first quarter” refers not to the moon’s appearance, but the fact that our natural satellite has now completed one quarter of its orbit around Earth, counting from the last new moon.) Everyone on Earth sees the same phase of the moon, although it is only above the horizon for about half the world at any given time.

At first quarter the moon always rises around mid-day and sets around midnight. This weekend you can see it shining like a celestial ghost in the daylit afternoon hours, and then continue to enjoy it in a dark sky until well past midnight. On each subsequent day, the moon will rise later and set later – but every clear evening this week will offer you terrific views of the moon, especially through binoculars and telescopes of any size. (The moon is always completely safe to look at using optical aids, when the sun is not nearby.)

The curved line, running top-to-bottom, that divides the lit and dark hemispheres of the moon is called the terminator. Anyone standing on the terminator is seeing the sun rising – on the moon, the Earth, or on any other spherical world. The sunlight arriving along the moon’s terminator is nearly horizontal – so it casts long shadows from every crater rim, mountain peak, hill, and boulder. With no atmosphere on the moon to scatter light and soften shadows, the dramatically lit terrain looks spectacular, especially under magnification. As the moon waxes fuller night after night, the terminator migrates across the moon from east to west – highlighting new regions. So head out on every clear night and see new things – or revisit the same locations to see how they change! For example, deeper craters that begin the week with dark, shadowed floors will fill with light as the sun climbs higher over them.

This week, the moon will reside in Virgo (the Maiden) on Sunday and Monday night, and then shift into neighboring Libra (the Scales) for Tuesday and Wednesday. After passing through Scorpius and Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer) next, the now gibbous moon will spend the coming weekend traversing the stars of Sagittarius (the Archer).

Here’s a fun assignment for you! On Thursday night, July 2, the terminator on the waxing gibbous moon will fall just to the left (or lunar west) of Sinus Iridum, the Bay of Rainbows. The circular, 249 km-wide feature is a large impact crater that was flooded by the same basalts that filled the much larger Mare Imbrium to its right (lunar east) – forming a rounded “handle” on the western edge of that mare.

The “Golden Handle” effect is produced by way the sun strikes the prominent curving Montes Jura mountain range surrounding Sinus Iridum on the north and west, and by a pair of protruding promontories named Heraclides and Laplace to the south and north, respectively. Your telescope will show you that Sinus Iridum is almost craterless – so we know that it is geologically young. But it does host a set of northeast-oriented dorsae or “wrinkle ridges” that are nicely revealed at this lunar phase. Don’t fret if you miss seeing it. The effect returns every month a few days before full moon.

The moon will reach its full phase on Sunday, July 5 at 12:44 am EDT, or 4:44 Greenwich Mean Time (GMT). The July full moon, commonly called the “Buck Moon”, “Thunder Moon”, or “Hay Moon”, always shines in or near the stars of Sagittarius or Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). The indigenous Ojibwe people of the Great Lakes region call this moon Abitaa-niibini Giizis, the Halfway Summer Moon or Mskomini Giizis, the Raspberry Moon. The Cree Nation of central Canada calls the June full moon Opaskowipisim, the Feather Moulting Moon (referring to wild water-fowl habits). The Mohawks call it Ohiarihkó:wa, the Fruits are Ripened Moon.

This full moon will feature a shallow partial penumbral lunar eclipse, the first eclipse to be visible in the Western Hemisphere during 2020. The eclipse will begin when the moon contacts Earth’s penumbral shadow at 03:07:23 GMT. At greatest eclipse at 04:30:02 GMT, only 35% of the moon will fall within the Earth’s southern penumbral shadow, barely darkening the moon’s northern limb. The penumbral eclipse will end when the moon exits Earth’s shadow at 05:52:27 GMT. The entire eclipse will be visible from all of Central and South America, the southeastern half of North America, and western Africa. The latter stages of the eclipse will be visible in the rest of the USA (except Alaska) and the western Canadian provinces. The rest of Africa and western Europe will see only the early stages.

The Planets

Have you seen Jupiter and Saturn dancing across the sky in the middle of the night? This week, the very bright, white speck of Jupiter will rise over the east-southeastern horizon shortly before 10 pm in your local time zone. Dimmer, yellow-tinted Saturn will follow it about 15 minutes later. (Every week, they will rise about half an hour earlier.) For the rest of this year, those two gas giant planets will dance across the sky together, with Saturn on Jupiter’s left (east). Look for the stars of Sagittarius (the Archer) and the Milky Way off to their right (west).

For now, Jupiter might catch your eye through a southerly window during the wee hours of the night. The two planets will only ascend to about 23 degrees above the horizon when they lay due south at 2 am local time. Before dawn you’ll find them sitting not very high above the southwestern horizon. Saturn will vanish into the brightening sky before Jupiter, but you could try to recover it with binoculars.

For several weeks, Jupiter and Saturn have been positioned above, and to either side of, a globular star cluster named Messier 75 (or NGC 6864). The magnitude 9.2 cluster should normally be visible in binoculars and backyard telescopes as a small, fuzzy patch – but this week’s brightening moon will suppress it. This week, the cluster will be located approximately a thumb’s widths to the lower right (or 1.5 degrees to the celestial southwest) of Saturn. Every morning, the planets’ orbital motions will carry them a little bit to the right (west) compared to the cluster. Next Sunday, Saturn will sit more or less directly over the cluster. Next week they’ll begin to leave it behind them.

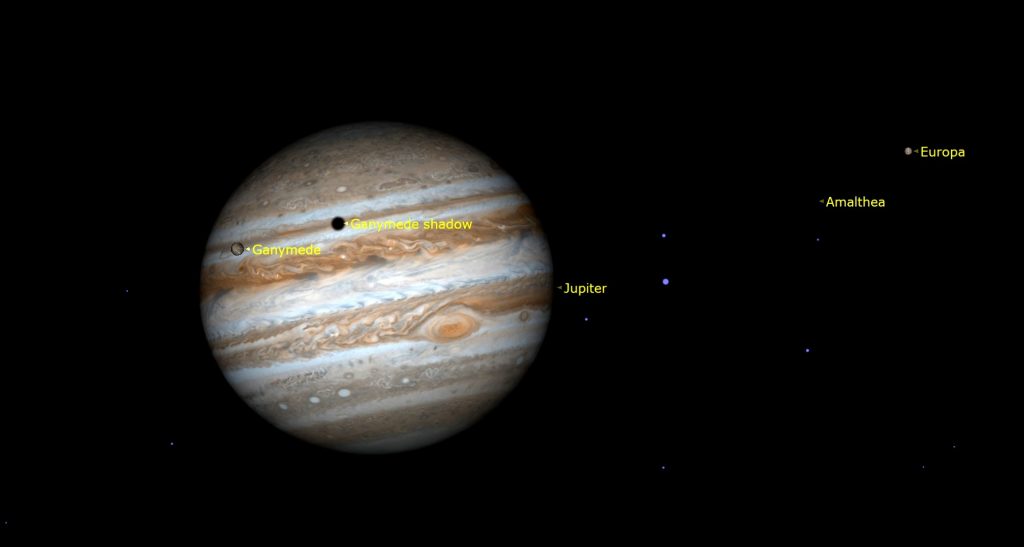

Even binoculars will reveal Jupiter’s four large Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto as they dance around the planet from night to night. And a modest-sized telescope will show Jupiter’s brown equatorial belts and the famous Great Red Spot. In the Eastern Time zone, the Great Red Spot will be crossing the planet’s disk starting in late evening on Tuesday and Thursday, and during the wee hours of Tuesday and Thursday, and before dawn on Saturday morning.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast onto Jupiter by its Galilean moons are visible in amateur telescopes as they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk for a few hours. Starting in late evening on Thursday, and continuing into Friday, observers in the Americas can see Ganymede’s relatively large shadow traverse the planet, accompanied by the Great Red Spot! Ganymede’s shadow will cross Jupiter’s northern hemisphere between 10:30 pm and 1:30 am EDT (or 02:30 and 05:50 GMT). The spot will complete its passage before the shadow.

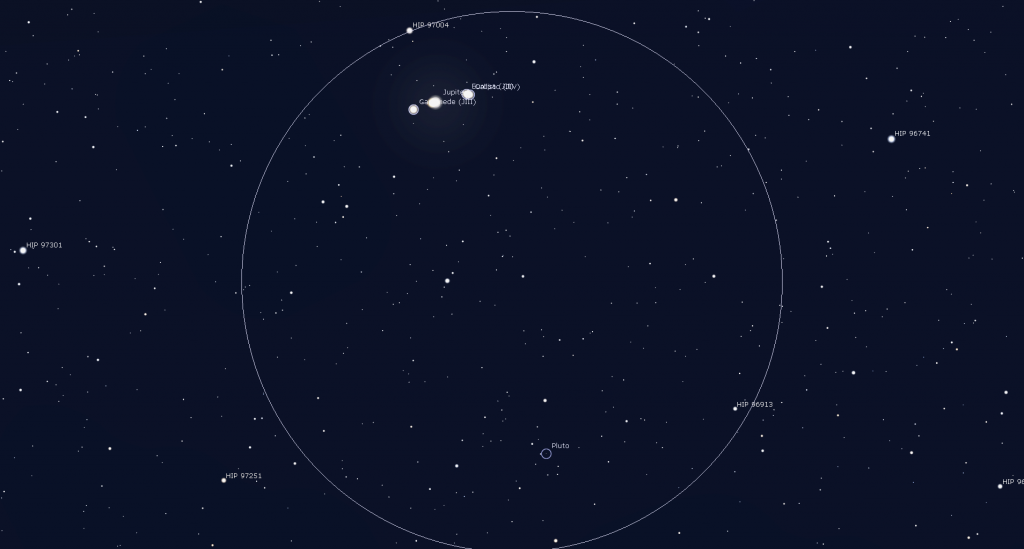

On the nights surrounding Wednesday, July 1, the faster orbit of Jupiter will carry it closely past distant and slower-moving Pluto. While the faint, magnitude 14.25 dwarf planet is not observable visually in amateur telescopes, nearby Jupiter will show amateur skywatchers where it is – less than a finger’s width below (or only 42 arc-minutes to the celestial south of) Jupiter. Since Earth is currently passing Jupiter and Pluto “on the inside track” around the sun, those planets will be appear to be moving westward retrograde through the stars around them.

Dust off your telescope! Even a small telescope will show Saturn’s rings and several of its brighter moons – especially its largest moon, Titan! Because Saturn’s axis of rotation is tipped about 27° from vertical (a bit more than Earth’s axis), we can see the top surface of its rings, and its moons can arrange themselves above, below, or to either side of the planet. During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from above Saturn tonight (Sunday) to below the planet next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope will flip the view around.)

Photo op! When the full moon rises over the southeastern horizon at dusk next Sunday evening, it will form a neat triangle below (to the celestial south of) Jupiter and Saturn. The moon and two planets will fit within the field of view of binoculars and will produce a lovely wide field photograph when composed with interesting foreground scenery. Over the course of the night, the diurnal rotation of the sky will shift the moon to the planets’ left, and the moon’s orbital motion will carry it closer to Saturn than Jupiter.

Mars has been speeding eastward along the ecliptic, causing it to rise long after Jupiter and Saturn. This week, Mars will be rising at about 1 am local time, and will remain visible as a prominent reddish dot until dawn, when it will be positioned about 3.5 fist diameters above the southeastern horizon. Mars is steadily increasing in disk size and brightness because Earth is travelling towards it this summer. You can’t miss it – nothing else near it is anywhere as bright, nor as red.

The dim and distant outer planets Uranus and Neptune are east and west of Mars, respectively. But I’ll hold off describing where they are until they are visible at a more convenient time.

Last up, literally, is Venus. Our sister planet has become the “Morning Star” – shining brightly in the eastern pre-dawn sky, where it will stay for the rest of 2020. This week, Venus will rise over the east-northeastern horizon just before 4 am local time. Viewed in a telescope or good binoculars, it will exhibit a waxing crescent shape. Watch for the bright, orange-tinted star Aldebaran, one corner of the triangular face of Taurus (the Bull), positioned to the lower left (celestial east) of Venus. Next weekend, Venus’ orbital motion will start to carry it directly through the bulls’ face!

By the way, we’re now in a period where, after Venus rises at 4 am local time, you can observe seven planets (which includes Earth, by looking down) at the same time – plus the dwarf planets Ceres in Aquarius and Pluto below Jupiter, if you have a large enough telescope! When Mercury appears after mid-July, it’ll be possible to see all eight classical planets!

Some Moonlight-Friendly Sights

If you missed last week’s roundup of sights to see on moonlit nights – with your unaided eyes, and through binoculars and backyard telescopes, I posted it with some sky charts here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

My Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National resume on Tuesday, June 30 from 3:30 to 5 pm EDT. This week, we’ll have fun exploring the link between stargazing and science fiction in books, film, and TV. Want to see which star Vulcan orbits? Or where to see a flux capacitor in the sky? Details and the schedule are here.

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory Youtube channel, where they offer free online viewing through their rooftop telescopes, including their brand new 1-metre telescope! Details are here.

Our David Dunlap Observatory Saturday night events may be cancelled, but we’re still pleased to offer the next best thing – a free online talk by University of Toronto Doctoral Candidate Emily Deibert. Tune in to the RASC Toronto Centre’s YouTube channel at 7:30 pm EDT on Saturday, July 4 to see her talk entitled Extraordinary Exoplanets. More information can be found here.

The Canadian organization Discover the Universe is offering astronomy broadcasts via their website here, and their YouTube channel here.

On many evenings, the University of Toronto’s Dunlap Institute is delivering live broadcasts. The streams can be watched live, or later on their YouTube channel here.

The Perimeter Institute in Waterloo, Ontario has a library of videos from their past public lectures. Their Lectures on Demand page is here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!