The Half Moon Hides Antares, Algol is Active, Saturn Shines Brightest, Venus Revives, and Cygnus Sights!

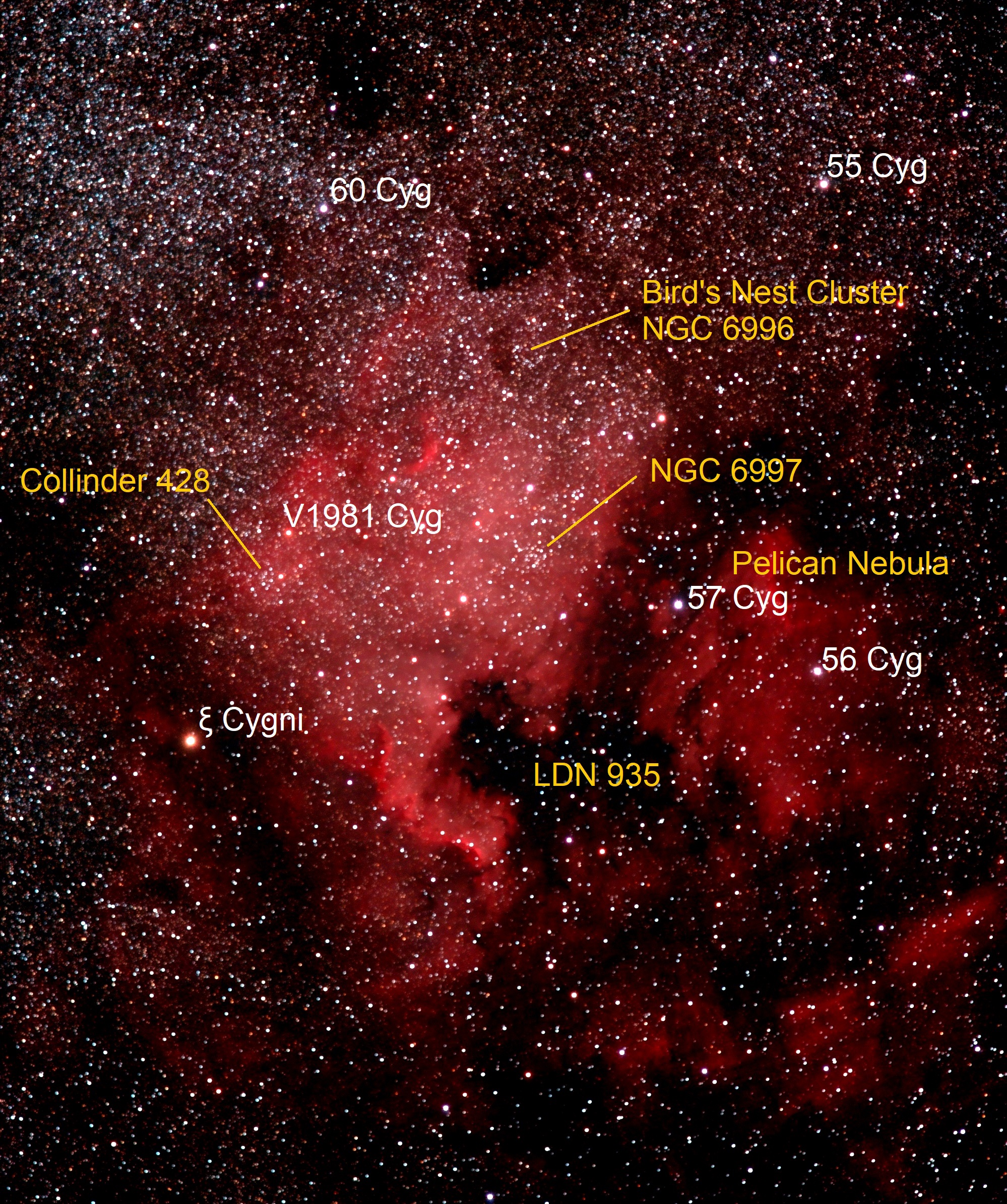

This image of the North American Nebula was captured in 2018 near Thornbury, Ontario by my friend Sailu Nemana. Several of the surrounding bright stars and star clusters within it are highlighted. The Pelican Nebula (at right) is formed by the dark dust of LDN 935. The re/pink colour is produced by ionized hydrogen gas. This photograph spans almost a palm’s width, top to bottom.

Hello, August Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of August 20th, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will shine in the evening sky this week, rewarding zoomed views as it waxes in phase, especially when it occults the bright star Antares. Moonlight won’t interfere much with the summer night sights until late this week, so we tour majestic Cygnus. Mysterious Algol’s dips in brightness return to evening, bright Jupiter and peak Saturn are shining overnight, and Venus returns as the Morning Star. Read on for your Skylights!

Active Algol

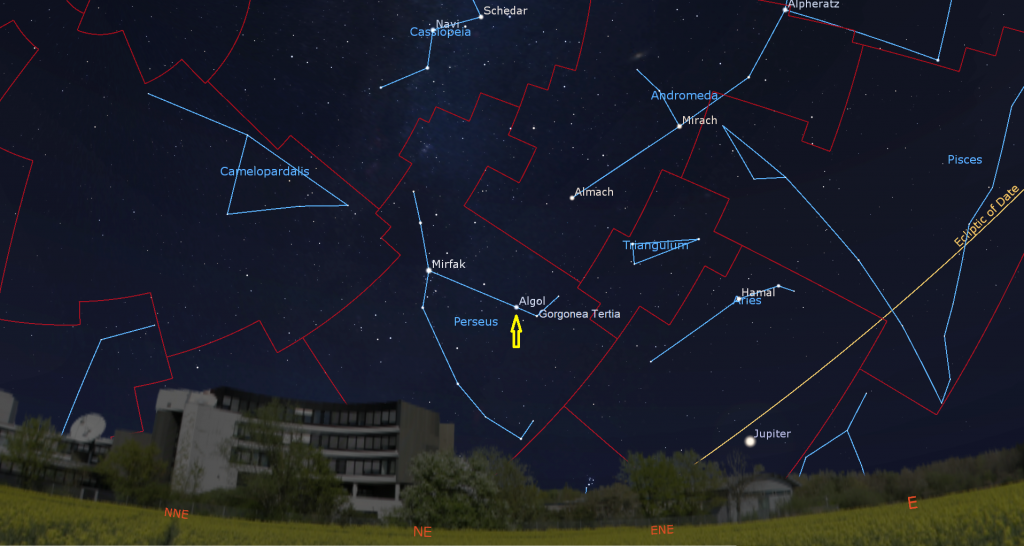

On late-August evenings the constellation of Perseus (the Hero) climbs the eastern sky. The easiest way to identify the constellation is to look for Perseus’ brightest star Mirfak, which will be shining about two fist widths below the W-shaped constellation of Cassiopeia (the Queen).

The second brightest star of Perseus (the Hero) is Beta Persei (β Per), better known as Algol, from the Arabic “Ra’s al-Ghul”, which means “the Demon’s Head”. Algol represents the pulsing eye of Medusa the Gorgon, whose severed head Perseus is carrying. The star represented the god Horus in Egyptian mythology and was Rosh ha Satan “Satan’s Head” in Hebrew.

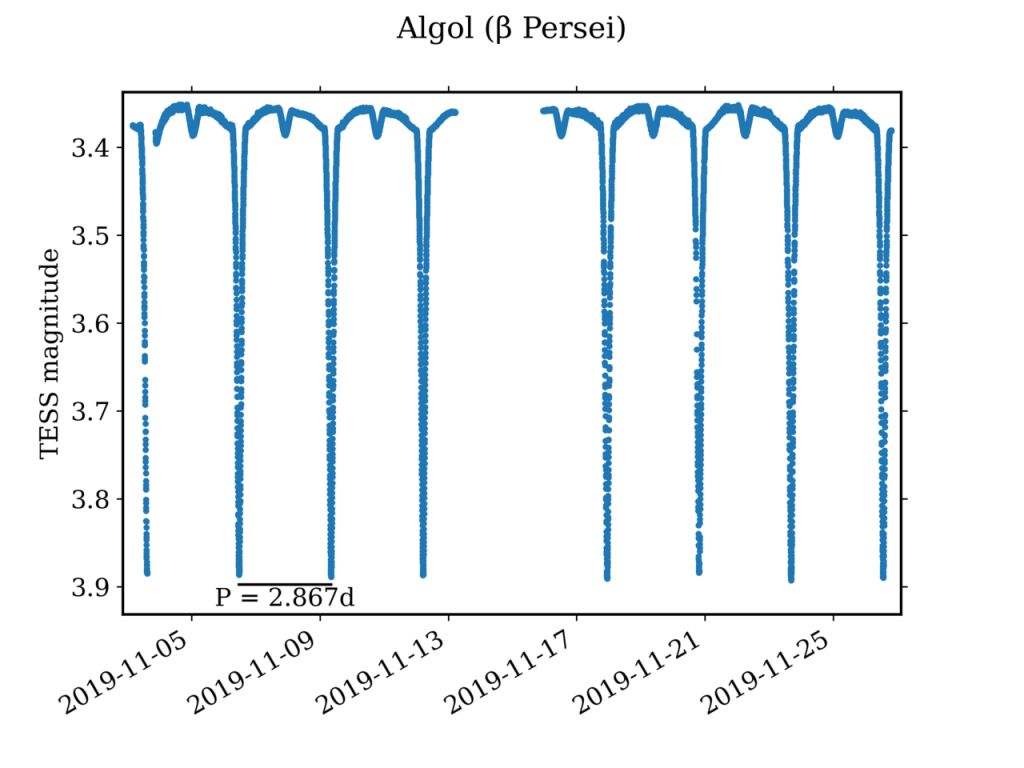

There’s a good reason for these scary associations. Ancient sky-watchers noticed that Algol is variable. Like clockwork, this star’s visual brightness dims noticeably once every 2 days, 20 hours, and 49 minutes. That happens because a dim companion star orbiting nearly edge-on to Earth crosses behind the much brighter main star. Once the eclipse begins, the light we see steadily drops in brightness for five hours. Then it ramps up again during another five hours – until the eclipse is over. Algol is the archetype for all eclipsing binary star systems, and is among the most accessible variable stars for beginner skywatchers.

The easiest way to monitor Algol’s variability is to note how bright that star looks compared to other, non-varying stars near it. When it isn’t dimmed, Algol shines at magnitude 2.1, similar in brightness to Almach, the bright star located a fist’s diameter above Algol (or celestial west) in Andromeda (the Princess). While dimmed, Algol fades to magnitude 3.4, about the same brightness as the star Gorgonea Tertia (or Rho Persei) located two finger widths to Algol’s right (or celestial south). Use your unaided eyes or binoculars to compare them.

For observers in eastern North America, fully dimmed Algol will sit in the lower part of the northeastern sky on Sunday, August 27 at 11:32 pm EDT (or 03:32 Greenwich Mean Time on August 28). The bright planet Jupiter shining off to its lower right (celestial south) will help you orient yourself. Five hours later the star will shine at full intensity from a perch high in the eastern sky. Observers in more westerly time zones can see the latter stages of the brightening.

The Moon

This will be the best week of the lunar month to view the waxing moon in evening – but better views for mid-northern latitude observers will come this fall when our natural satellite will shine higher in the evening sky.

After the moon passes the sun at new moon each month, it re-appears in the western sky after sunset. As the moon’s orbit around Earth carries it farther from the sun every day, the moon sets later. Meanwhile, its increasing angle from the sun causes it to wax in illuminated phase. The boundary between the moon’s lit and dark hemispheres is called the terminator. Anyone standing along that line on the moon would see the sun rising. The nearly horizontal rays of sunlight striking the moon there cast long shadows to the west of every bump, hill, mountain, crater rim, and mountain peak. Crater floors remain dark while their rims are lit up. With no air on the moon to scatter light, all the shadows are inky black.

Any pair of binoculars or backyard telescope will show the spectacular sights along the terminator. Since that boundary migrates west across the moon hour-by-hour and night-after-night, new features are highlighted every time you look. The terminator becomes a straight line at first quarter and then increasingly curves the opposite way, converting the moon from a crescent, to half-illuminated, to gibbous on its way to full moon. That change told ancient astronomers that the moon was a sphere.

Let’s break down this week’s moon meet-ups. Today (Sunday) the crescent moon will rise in mid-morning. Once the sky darkens after dusk, the moon will be posing a palm’s width to the right (or 6° to the celestial northwest) of Spica, the brightest star in Virgo (the Maiden). On Monday night the moon will jump to Spica’s upper left.

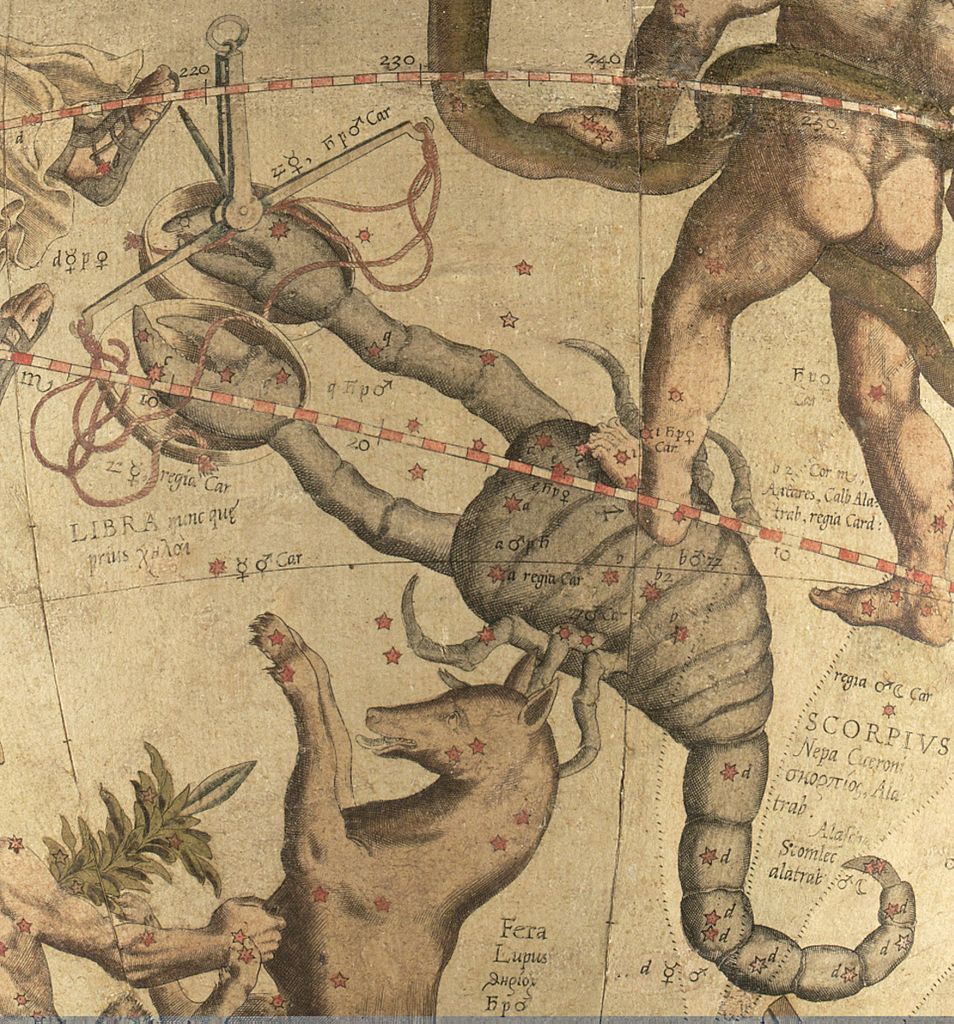

The moon will spend Tuesday and Wednesday crossing Libra (the Scales). Its stars were once used as the pincer tips of next-door Scorpius (the Scorpion). The scorpion’s brightest star is orange-tinted Antares, the “Rival of Mars”. Several medium-bright, white stars arranged in a roughly vertical line to the right (or celestial west) of Antares mark the creature’s claws on modern sky charts. The rest of the scorpion extends downward to the south, and then curls left (eastward) into the Milky Way. It terminates at the bright double star Shaula, which marks its poisonous stinger. Observers above mid-northern latitudes might not be able to see the southernmost stars of the constellation.

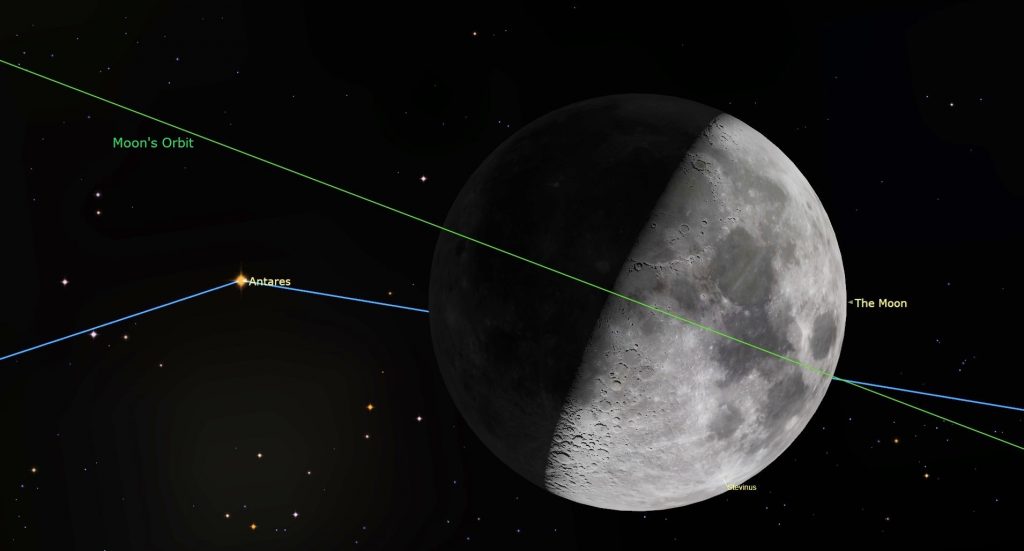

The moon will complete the first quarter of its journey around Earth on Thursday morning at 5:57 am EDT, 2:57 am PDT, or 09:57 GMT. On Thursday night, August 24 observers in Northern Mexico, most of the continental USA, and parts of southern and central Canada can watch the bright, waxing gibbous moon occult Antares, the brightest star in Scorpius. For the surrounding regions, the event will occur in a bright sky, or the moon will set during the occultation. The event can be seen with unaided eyes, but will look best through binoculars and backyard telescopes. Times vary by location, so use an app like Stellarium to look up the circumstances where you live. In Detroit, MI the dark leading edge of the moon will cover Antares at 10:36 pm EDT. The star will emerge from behind the bright limb of the moon, near the big crater Stevinus, at 11:36 pm EDT. The pair will be setting in Toronto at the end of the event.

On Friday night, the waxing gibbous moon (now more than half full) will shine in Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer). That constellation, which shines above the scorpion, should have been a Zodiac constellation because the sun passes through his southern region from late November to mid-December each year.

The brightening moon will end the week next Sunday inside the Teapot-shaped stars of Sagittarius (the Archer).

The Planets

If you live closer to the tropics than I do, you might be able to glimpse Mercury and Mars shining about a palm’s width apart above the western horizon, with Mars above Mercury, immediately after sunset this week.

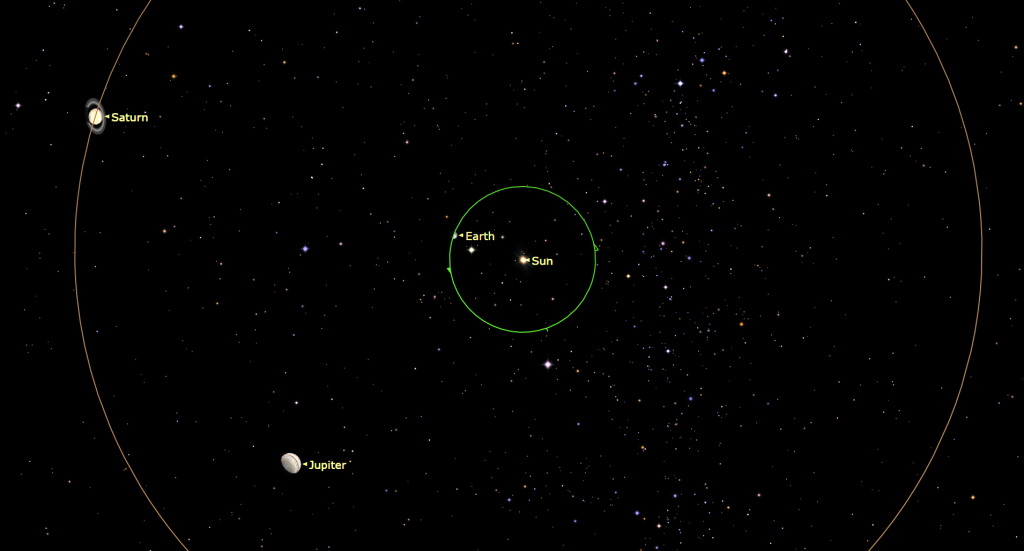

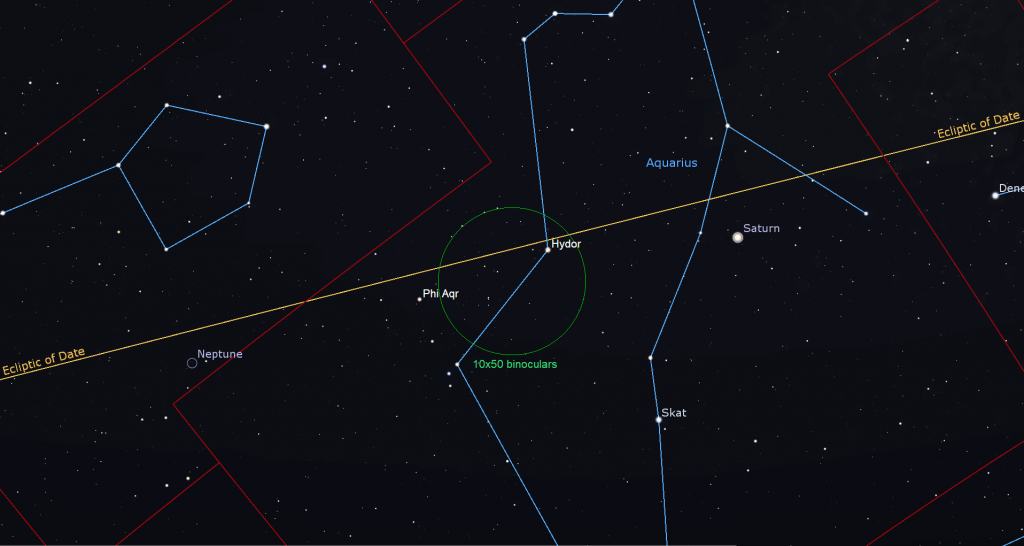

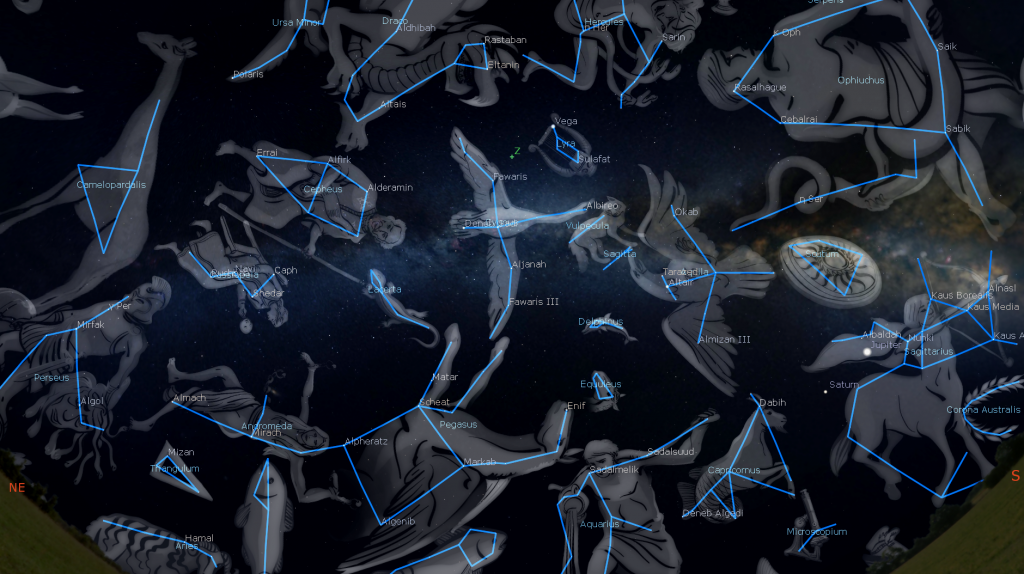

Except for the North Polar zone, everyone on Earth will be able to see the bright, yellowish dot of Saturn shining in the overnight sky. For mid-northern latitude observers, the ringed planet will rise around sunset and spend the night crossing the sky. That’s because, a few hours after midnight on Saturday, August 26 in the Americas, Saturn will reach opposition for 2023.

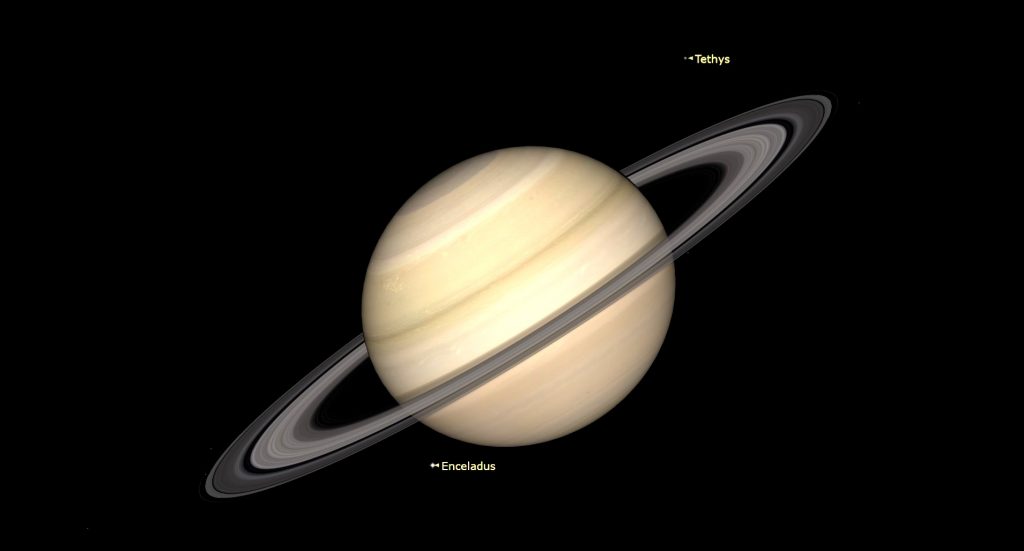

Planets at opposition rise at sunset and set at sunrise because Earth is positioned between them and the sun. On Saturday night, Saturn will be at a distance of 1.311 billion km, or 73 light-minutes from Earth. It will shine at magnitude of 0.41 – its brightest for the year. While planets always look their brightest at opposition, Saturn’s brilliance will be boosted by the Seeliger effect – backscattered sunlight from its rings. In a telescope Saturn’s globe and rings will show maximum apparent diameters of 19 arc-seconds and 44 arc-seconds, respectively. Opposition is also the optimal time to view Saturn’s moons through a backyard telescope in a dark sky.

Don’t fret if it’s cloudy on Saturday. Saturn will look great any night. The planet will clear the rooftops by about 9:30 pm – but you’ll get the clearest views of Saturn in a telescope between 11 pm and 4 am, when it’s highest. (Those times will advance by half an hour each week.) The faint stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) will be shining around Saturn, the bright trio of the Summer Triangle asterism stars will sparkle well above, and the Great Square of Pegasus will be off to the planet’s upper left. The very bright star Fomalhaut (or Alpha Piscis Austrini, the Southern Fish) will shine two fist diameters below Saturn all year.

Saturn’s beautiful rings are visible in any size of telescope. If your optics are of good quality and the air is steady, try to see the Cassini Division, a narrow gap curving between the outer and inner rings, and a faint belt of dark clouds that encircle the planet’s globe. Remember to take long, lingering looks through the eyepiece – so that you can catch moments of perfect atmospheric clarity. Good binoculars can hint at Saturn’s rings, too.

From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves above, below, and alongside the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the planet’s upper right (celestial west) tonight (Sunday) to Saturn’s lower left (celestial east) next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope? You may be surprised at how many you can see if you look closely. Saturn will be available for our evening viewing pleasure through its opposition in late August and then on until mid-winter! This summer the blue ice giant planet Neptune, currently 840 times fainter than Saturn, will be lurking about two fist diameters to Saturn’s left, or 23° to its celestial northeast.

The planet party will reach its peak when brilliant, white Jupiter, which currently shines about 15 times brighter than Saturn, rises around 11 pm local time. This year Hamal and Sheratan, the brightest stars of Aries (the Ram), will shine a generous fist’s diameter above the giant planet. Jupiter should catch your eye while it gleams high in the southern sky before sunrise.

Binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons in a line beside the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. All four of them will huddle to the west of Jupiter tonight (Sunday). On Monday, Jupiter will cruise past a medium-bright star named Sigma Arietis, temporarily adding a fifth moon to the mix for several nights.

Jupiter will climb high enough for good telescope views after about 1 am local time. It’ll look even better from then until dawn. Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk on early on Wednesday and Friday morning, and before dawn on Tuesday, Friday and next Sunday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Saturday morning, August 26, Io’s small shadow will cross Jupiter’s equatorial region from 4:58 to 7:03 am EDT (or 08:58 to 11:03 GMT), though the sky will be brightening in the Eastern Time zone at the end of its transit.

The blue-green ice giant planet Uranus will be following Jupiter across the sky this year. This week it will be located less than a fist’s diameter to the bright planet’s lower left (or 8° to the celestial east). The bright little Pleiades Star Cluster will be located a similar distance to Uranus’ left. Magnitude 5.8 Uranus is visible in binoculars and small telescopes if you know where to look. I’ll get more specific in the coming weeks when it will climb higher.

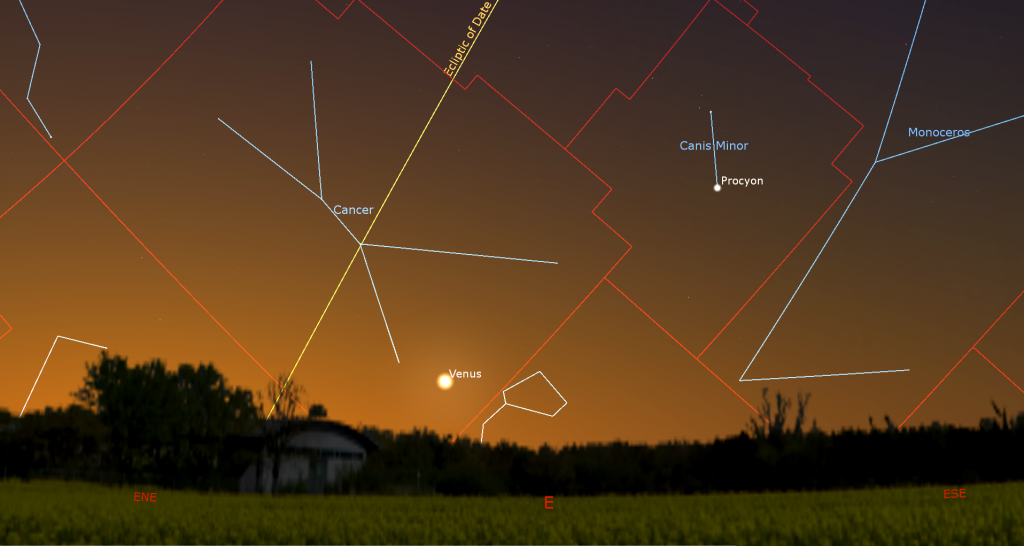

Fresh from its trip past the sun last week, the brilliant planet Venus will join the eastern pre-dawn sky this week, where it will shine until mid-winter. The planet will climb farther from the sun with each passing day, so expect to see it more easily after mid-week. The planet will be sitting low in the eastern sky. In a telescope, it will exhibit a large disk and a very slim waxing crescent phase. Turn all optics away from the eastern horizon before the sun rises.

Soaring with Cygnus

The moon will not brighten the evening sky very much until later this week. And with darkness arriving a bit earlier, and evening temperatures being mild and bug-free, this will be a great time to get out under the stars.

Objects in the sky directly overhead will always appear at their best because you are seeing them through the least amount of intervening air. In early evening during late August every year, the constellations of Lyra (the Harp), Cygnus (the Swan), and Draco (the Dragon) surround the zenith. Two weeks ago I toured Lyra here, highlighting some of the objects you can look at with binoculars and small telescopes. This time we’ll soar with Cygnus!

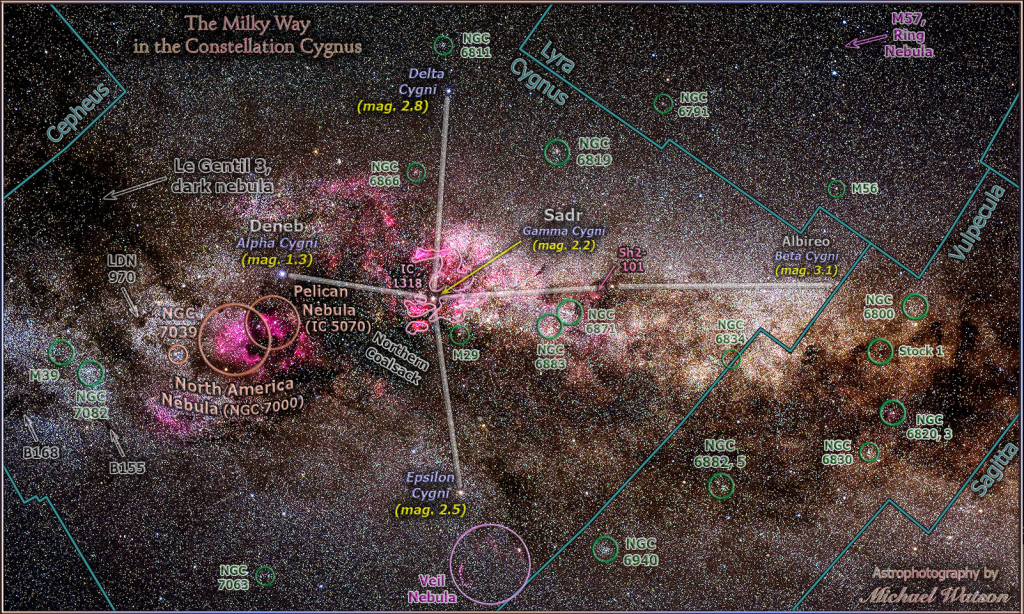

Head outside on the next clear evening, face south, and look nearly overhead for the very bright star Vega. To its left is the realm of the great constellation Cygnus (the Swan). Its brightest stars also form the asterism called the Northern Cross. In size, Cygnus is the 16th largest of the 88 official constellations. By using your closed fist held at arm’s length, you can see that the bright stars of the swan span more than two fists (or 22°) head to tail, and nearly four fists (or 36°) across the wingspan. Its official boundary includes a large northeastern section that is devoid of bright stars, but is loaded with rich nebulae and star fields.

Cygnus’ position 40° north of the celestial equator allows the constellation to be visible from every city on Earth. Antarctica sees no portion of it, observers at the southern tip of South America only ever glimpse its southernmost stars, and the rest of the Southern Hemisphere sees it only at this time of year – on (their) late-winter, early spring evenings. For observers in mid-northern latitudes around the world, some of Cygnus’ more northerly stars are circumpolar – that is, they never drop below the horizon.

This constellation is one of the few that truly resembles its name. In Greek mythology, Cygnus was Zeus disguised as a beautiful swan to seduce Leda, the mother of Helen of Troy. Cygnus was also said to represent mourning Orpheus, his harp in the form of nearby Lyra (the Lyre). The Arabs envisaged the stars of Cygnus as a hen. The Dakota people of North America saw a salamander, the Ojibwa people imagined a crane, and the Mongolians a bow and arrow. Ancient Chinese astronomers used a different grouping of stars and formed a bridge of magpies crossing the river of the Milky Way.

When you face south, the swan is flying down toward the right. Starting at Vega, shift your gaze 2.3 fist diameters to the left (or 23° or to the celestial east) to the bright, blue-white star Deneb, which marks the tail of the swan. (The name means “tail” in Arabic.) Shining at magnitude 1.25, Deneb is the brightest of the swan’s stars, so it is also named Alpha Cygni. Can you tell that it is several times fainter than Vega’s magnitude 0.00?

Deneb is located at a whopping 2,550 light-years away from our solar system. It shines as brightly as it does because this luminous, supergiant star emits many tens of thousands of times more visible light than our Sun. The slow wobble, or precession, of the Earth’s rotation axis will cause Deneb to replace Polaris as Earth’s northern Pole Star around the year 9,800. The last time it did so was around 16,000 BCE.

Sadr is the prominent star located about a palm’s width to the lower right (or 6° to the celestial southwest) of Deneb. It marks the centre of the swan’s body (and the giant cross). The name is derived from an Arabic expression for “the hen’s breast”. Even though it’s somewhat closer to us (1,800 light-years) than Deneb, Sadr (or Gamma Cygni) shines about 2.5 times fainter than Deneb. It’s also somewhat cooler than Deneb, giving it a creamier colour.

The swan’s head is marked by a much dimmer star named Albireo. That star sits approximately 1.6 fist widths to the lower right (or 16° to the celestial southwest) of Sadr – swans have long necks! Albireo is also parked close to the centre of the Summer Triangle asterism. Albireo is a favorite telescope target at summer star parties because it divides into a coloured double star when viewed in a small telescope. The two stars show as a lovely sapphire (blue) and topaz (yellow) in colour because their photospheres are 11,000 K and 4,400 K, respectively.

Measurements from the Gaia Space Telescope indicate that Albireo is likely only a line-of-sight double – a happenstance of geometry from our perspective. The brighter yellow star sits 328 light-years away from us, and the dimmer blue star is 389 light-years away. They’re close enough to one another to be gravitationally bound together – but Gaia found that they are travelling in much different directions – uncommon in stellar siblings. Albireo was given its single name before telescopes were invented and revealed that it was actually a duo. Its alternate designation is Beta1,2 Cygni. The numerals refer to each partner.

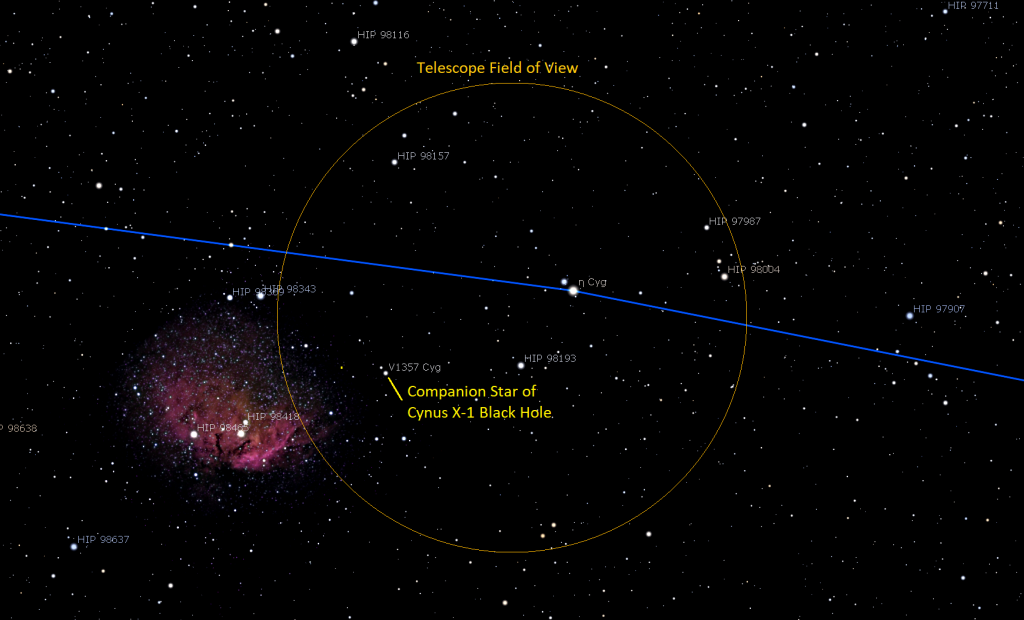

See if you can spot a medium-bright star positioned about midway along the swan’s long neck, between Sadr and Albireo. That’s Eta Cygni or (η Cyg), a warm-tinted star located about 135 light-years from Earth. This aging star has started to fuse helium in its core. Strong binoculars and backyard telescopes can reveal a magnitude 8.8, blue-white star named HD 226868 and V1357 Cygni sitting 26 arc-minutes (a full moon’s diameter) to the lower left (or celestial east) of Eta. This hot, O-class star is emitting copious amounts of X-ray radiation.

In 1971, astronomer Tom Bolton of the University of Toronto used the 74” telescope at the David Dunlap Observatory in Richmond Hill, Ontario to analyze the light from V1357. He determined that something dark and massive was tugging it around in an orbit that repeated every 5.6 days. That invisible object came to be known as Cygnus X-1, the first confirmed black hole! The Canadian rock band Rush wrote a song about it. Listen to it on YouTube here! Astro-imagers who have photographed the nearby HII emission nebula named the Cygnus Star Cloud (or Sharpless 2-101) have likely included the Cygnus X-1 system, “invisible to telescopic eyes”!

With Deneb, Sadr, Eta Cygni, and Albireo running tail to head, you should now be able to locate a long, crooked chain of slightly dimmer stars arranged from lower left to upper right – forming the swan’s broad wings. Ancient Arab astronomers dubbed those stars “the Riders” – like a camel caravan, perhaps? Each wing extends about two fist diameters from Sadr and contains three stars. Let’s tour the wings.

Moving less than a fist’s width to the upper right (or 8° to the celestial northwest) from Sadr, we first arrive at Fawaris or Al Fawaris (“the Riders”) also known as Delta Cygni or (δ Cyg). The star has also been called Rukh, after the giant Roc in Middle Eastern mythology (and some sword and sandal movies). Decent telescopes at high magnifications should be able to split that star into a pair of greenish-blue and yellow-white stars. Al Fawaris will also take a turn as Earth’s pole star.

A further jump of 7° to the upper right lands us at white Iota Cygni or (i Cyg). A couple of finger widths beyond Iota sits yellowish Kappa Cygni or (κ Cyg), the wingtip star. Kappa is an aging G-type star (like our sun) – buts it has swelled to almost ten times the size of the sun. Both Iota and Kappa sit about 120 light-years away from us. Kappa is sometimes labelled on sky charts as Fawaris I.

Let’s trace out the lower wing. Moving about 8° downwards to the left from Sadr we find the bright, yellow-orange star Aljanah or Gienah, both names originating from the Arabic expression for “Wing of the Swan”. Also known as Epsilon Cygni or (ε Cyg), 72 light-years distant Gienah is an old star that is beginning its death process.

A palm’s width to the lower left of Gienah you should spot a medium-bright, yellow-orange star named Zeta Cygni or ζ Cyg or Fawaris III. A little more bending to the left and another palm’s width jump arrives at the tightly separated double star Mu1,2 Cygni or (μ1,2 Cyg). This pair of stars is orbiting one another with a period of about 790 years. Because their orbit is nearly edge on to us, they slowly move closer together and draw farther apart over the decades. Right now they are separating.

If you can leave the light polluted skies of the city, notice how the Milky Way divides into two strips where it passes through Cygnus. The dark median between those zones is opaque interstellar dust concentrated within the plane of our galaxy. Grab your binoculars and look for some of Cygnus’ wonderful nebulae – clouds of mainly hydrogen gas and dust that glow in pinks and blues – lit from within by the radiation emitted by the stars they contain. These large objects are best seen with binoculars, and sometimes your unaided eyes, under very dark, moonless skies. Check them out!

A few finger widths to the lower left of Deneb is the North American Nebula (also NGC 7000), so-named for its distinctive shape. It’s quite easy to see as a faint, bright patch in binoculars. It’s more than three times larger than a full moon. The Pelican Nebula, a smaller patch to its right, is part of the same gas cloud – but separated from the other piece by dark foreground dust.

A faintly glowing region called the Gamma Cygni Nebula surrounds Sadr. This nebula, which is nearly 5,000 light-years away from us, spans six full moon diameters across! Sadr is not related to the nebula, though – the star is only half as far away as the nebula. Before moving on, look for an extra-dark patch of sky sitting two finger widths to the upper left of Sadr. The patch, almost a fist diameter across and several finger widths tall is more dark interstellar dust that is blocking the light from the Milky Way’s stars beyond it. The patch is also known as the Northern Coalsack. (The larger, darker, geniune Coalsack Nebula is located beside Crux, the Southern Cross. But it’s only visible from the Southern Hemisphere.)

The large, delicate, and pink Veil Nebula or Cygnus Loop sits about three finger widths below Aljanah / Gienah. Its roughly circular shape, five full moon diameters across, is the tattered remnant shell of a supernova that occurred five to eight thousand years ago. A particularly strong section of the nebula sweeps across a foreground star named 52 Cygni. That star sits a few finger widths below Aljanah / Gienah. Put your lowest magnification eyepiece in your telescope, point it at 52 Cygni, and then look for a narrow slash of dim light crossing the field of view through the star. Then you can carefully follow the giant loop across the stars – especially if you have a nebula filter in your telescope.

Telescope owners should look for the Blinking Planetary or NGC 6826. It’s a stellar corpse (like Lyra’s Ring Nebula) that plays an optical illusion on you. When you look straight at it, its central white dwarf shines as a tiny pinprick. But use averted vision, and a blue halo pops into view. You can make the halo appear and disappear by shifting your gaze. It’s fun! Find the object by doubling a line drawn from Kappa through Iota.

If you are observing from a dark location, you should see that the band of the Milky Way runs directly through Cygnus – as if she is about to land on that river! The rich star fields surrounding the constellation are terrific for laying back and scanning with binoculars. You might find one of the many open star clusters in Cygnus, such as the Cooling Tower Cluster (or Messier 29), which is located less than two finger widths below Sadr, two more bright clusters along the neck to the left of Eta Cygni, the bright cluster Messier 39 located a fist’s diameter to the upper left of Deneb, and several clusters surrounding Delta Cygni.

Let me know how your exploration of Cygnus goes.

Aquila the Eagle

If you missed last week’s sky tour of the venerable constellation of Aquila (the Eagle), I posted it with sky charts here.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

Taking advantage of the crescent moon in the sky this week, the RASC Toronto Centre astronomers will hold their monthly City Sky Star Party in Bayview Village Park (a short walk from the Bayview TTC subway station), starting after dusk on the first clear weeknight this week (Mon to Thu only). Check here for details, and check the banner on their website home page or Facebook page for the GO or NO-GO decision around 5 pm each day.

Eastern GTA sky watchers are invited to join the RASC Toronto Centre and Durham Skies for solar observing and stargazing at the edge of Lake Ontario in Millennium Square in Pickering on Friday evening, August 25, from 7 pm to midnight. Details are here. Before heading out, check the RASCTC home page for a Go/No-Go call – in case it’s too cloudy to observe.

On Sunday afternoon, August 27 from 12:30 to 1 pm EDT, head to the David Dunlap Observatory for in-person DDO Sunday Sungazing. Safely observe the sun with RASC Toronto astronomers! During the session, which is for ages 7 and up, a DDO Astronomer will answer your questions about our closest star – the sun! Registrants will be given an eclipse viewer, learn how the sun works and how it affects our home planet, view the sun through solar telescopes, weather permitting, and visit the giant 74” telescope. More information is here and the registration link is here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcast with RASC National returns on Tuesday, August 29 at 3:30 pm EST. The Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy team will head to York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory for a live tour and chat about York U’s astronomy program and outreach activities. We’ll end the show by highlighting our final batch of RASC Finest NGC objects. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!