The Moon Waxes to Hunter Full, But We Can Still See Paired Stars and Pretty Planets!

During evening in early October, the Great Square of Pegasus is visible in the eastern sky. the horse’s nose star, Enif, shines about two fist diameters to the right of the square. Orange-tinted Enif has a tiny companion star visible in binoculars and backyard telescopes. The spectacular globular star cluster named Messier 15 (upper right) shares the binoculars field of view with Enif. (Stellarium)

Hello, October Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of October 2nd, 2022 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will wax from first quarter to full moon this week – but its bright light won’t prevent stargazers worldwide from enjoying bright planets in evening, Mercury at sunrise, and some binoculars double stars. Read on for your Skylights!

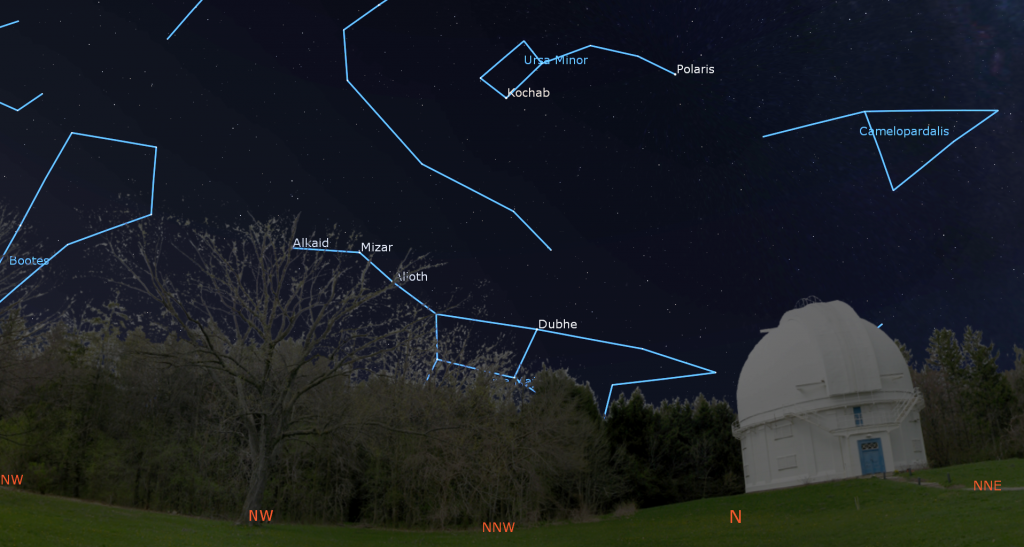

The Big Bear Hibernates

Have you tried looking for the Big Dipper lately? In early October every year, that asterism, which is circumpolar for observers located north of 35° North latitude, reaches its lowest position above the northern horizon in late evening – as if it is scooping up a bowl of cold, refreshing northern water! Its stars might not even clear the treetops where you live.

North American indigenous traditions tell the tale of the Great Bear (Ursa Major) heading into her den for winter. Wounded by pursuing birds (the Big Dipper handle stars Alkaid, Mizar, and Alioth), the bear’s blood dripped to Earth, staining the fall foliage red. Come spring, the bear will emerge from her slumber and begin to climb the northeastern evening sky.

The Moon

This is the week of the lunar month when our natural night-light will flood the sky with moonlight as it waxes from first quarter to full. The moon will formally complete the first quarter of its journey around Earth tonight (Sunday, October 2) at 8:14 pm EDT or 5:14 pm PDT. That translates to Monday, October 3 at 00:14 Greenwich Mean Time. At first quarter, the moon always rises around mid-day and sets around midnight, so it is also visible in the afternoon daytime sky, too. The evenings surrounding first quarter are the best ones for seeing the lunar terrain when it is dramatically lit by low-angled sunlight, especially along the terminator, the pole-to-pole boundary that separates the lit and dark hemispheres.

Tonight’s moon will shine inside the Teapot-shaped stars of Sagittarius (the Archer). If we had been creating a constellation for those stars, instead of the ancients, we’d be calling it Ollam Medicandi (the Teapot)!

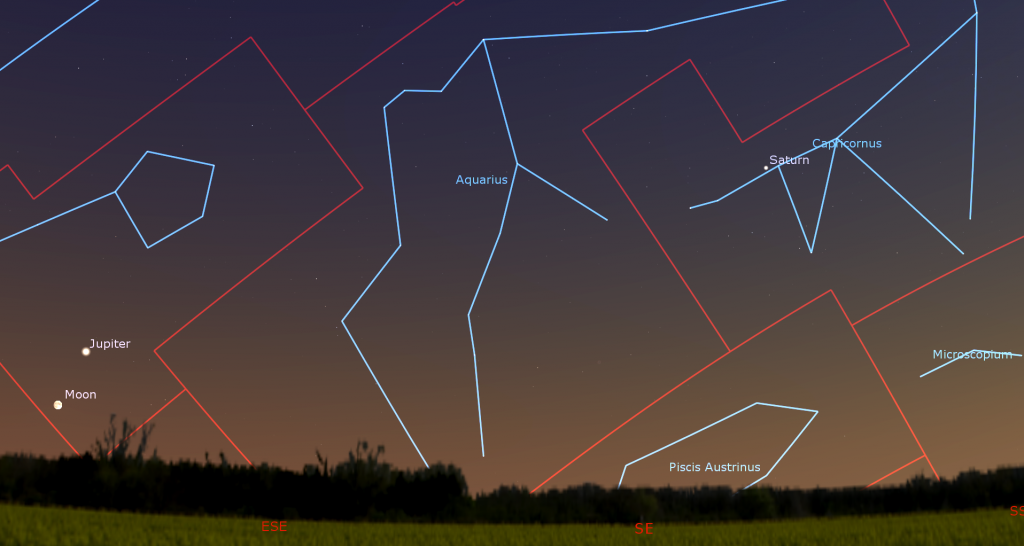

For the rest of the week, the moon will wax fuller (and brighter), and set 55 minutes later each night due to its increasing angle from the sun. The moon will stay within Sagittarius on Monday and then hop past Saturn in Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) from Tuesday to Wednesday. To my eyes, Capricornus’ stars look more like a bikini bottom than a sea-goat. The waxing gibbous moon will spend Thursday and Friday nights crossing through the faint stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer).

The moon will spend the coming weekend swimming eastward along the border between Pisces (the Fishes) above and Cetus (the Whale) below. On Saturday night the earlier sunsets will allow the nearly full moon to clear the eastern rooftops shortly after 7:30 pm local time. Once it does, watch for the very bright planet Jupiter shining several finger widths above (or 3.5° to the celestial northwest of) it – allowing the duo to share the view in binoculars all night long as they cross the night-time sky. By the time they set around 6:30 am local time, the diurnal rotation of the sky will swing the moon above Jupiter. Due to the moon’s continuous easterly orbital motion, skywatchers viewing the duo later, or in more westerly time zones, will see the moon positioned a little farther from the planet.

On Sunday at 4:55 pm EDT (or 1:55 pm PDT or 20:55 GMT), the moon will officially reach its full phase. The October full moon, which always occurs among the stars of Cetus or Pisces, is traditionally called the Hunter’s Moon and, appropriately for Halloween season, the Blood Moon, or Sanguine Moon (not to be confused with an eclipsed “blood moon”). Indigenous groups have their own names for the full moons, which lit the way of the hunter or traveler at night before modern conveniences like flashlights. The Anishinaabe people of the Great Lakes region call this moon Binaakwe-giizis, the Falling Leaves Moon, or Mshkawji-giizis, the Freezing Moon. The Cree Nation of central Canada calls the October moon Opimuhumowipesim, the Migrating Moon – the month when birds are migrating. The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois / Mohawk) of Eastern North America call it Kentenha, the Time of Poverty Moon.

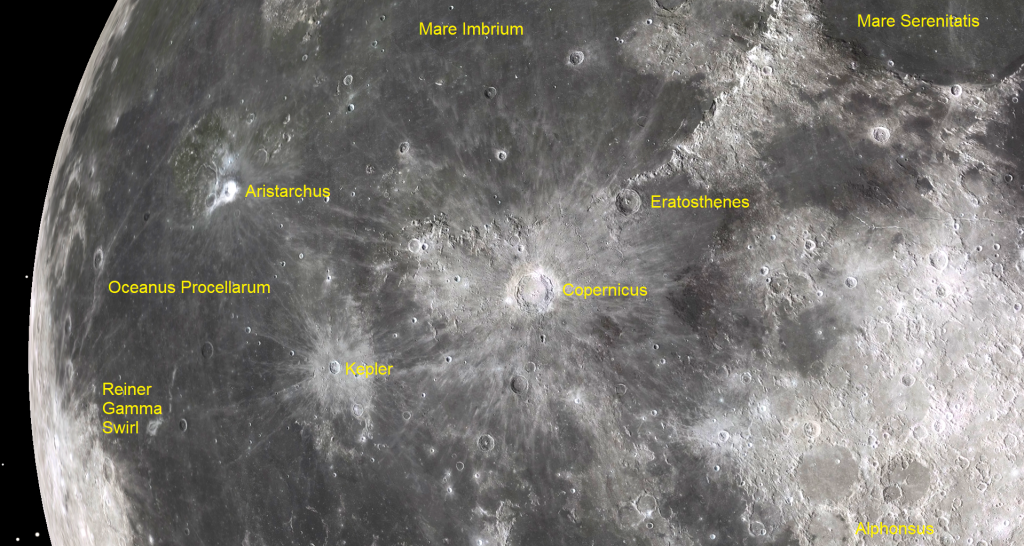

When you face any full moon, the sunlight shining upon it is coming from directly behind you – the same way the projector in the rear of a cinema lights up the movie screen in front of you. That sunlight is arriving straight-on to the moon’s surface – from directly overhead if you were standing on the moon – so it doesn’t generate any shadows. Every variation in brightness and colour you see on a full moon is due entirely to the moon’s geology, not its topography! That allows you to easily distinguish the dark, grey basalt rocks from the bright, white, aluminum-rich anorthosite rocks.

The basalts overlay the various lunar maria, Latin for “seas” – coined because people used to think they were water-filled. The maria are giant bowls or basins excavated by major impactors early in the moon’s geologic history and then infilled with dark basaltic rock that upwelled from the interior of the moon later in the moon’s geological history. Those “younger” areas have fewer impact craters on them.

The much older and brighter parts of the moon are composed of anorthosite rock. Those areas are higher in elevation and are heavily cratered because there is no wind and water, or plate tectonics, to erase the scars of the impacts. By the way, the bright, white appearance is produced by sunlight reflecting off of the crystals the rock is made of – the same sort of crystals you see in the granite countertops in Earth’s kitchens. And yes, there are coloured rocks on the moon.

Some of the violent impacts that created the craters in the highland regions also threw bright streams of ejected material far outward and onto the darker maria. We call those streaks lunar ray systems. Some rays are thousands of km in length – like the ones emanating from the very bright crater Tycho in the moon’s southern central region.

Use your binoculars to scan around the full moon (or even a night or two before and after full). There are smaller ray systems everywhere! There are also places where craters punched into the maria have ejected dark rays on to white rocks. And, since the dark basalt overlays the white, older rock below, you can find lots of craters where a hole has been punched through the dark rock, producing a white-bottomed crater!

The prominent crater Copernicus is located in eastern Oceanus Procellarum – due south of Mare Imbrium and slightly to the upper left (lunar northwest) of the moon’s centre. This 800 million year old impact scar is visible with unaided eyes and binoculars – but telescope views will reveal many more interesting aspects of lunar geology. Several nights before the moon reaches its full phase, Copernicus exhibits heavily terraced edges (due to slumping), an extensive ejecta blanket outside the crater rim, a complex central peak, and both smooth and rough terrain on the crater’s floor. Around full moon, Copernicus’ ray system, extending 800 km in all directions, becomes prominent. Copernicus’ rays are squiggly, as opposed to Tycho’s arrow-straight ones. Use high magnification to look around Copernicus for small craters with bright floors and black haloes – impacts through Copernicus’ white ejecta that excavated dark Oceanus Procellarum basalt and even deeper highland’s anorthosite.

Several of the maria link together to form a curving chain across the northern half of the moon’s near-side. Mare Tranquillitatis, where humanity first walked upon the moon, is the large, round mare in the centre of the chain. You can plainly see that this mare is darker and bluer than the others, due to its basalt being enriched in the mineral titanium. That’s one of several reasons why Apollo 11 was sent to that location. Another is that its southern edge is close to the moon’s equator. Equatorial landing sites required less fuel and fewer course corrections of the spacecraft.

By the way, Earth-bound telescopes – even the largest ones – cannot see the items left by the astronauts on the moon. When the air is particularly steady, the smallest feature you can see on the moon with your backyard telescope is about 2 to 6 km across – far larger than a lunar module descent stage. Only the cameras on spacecraft in orbit around the moon can photograph astronauts’ footprints, lunar rover tracks, and equipment.

Morning Zodiacal Light for Mid-Northern Observers

During autumn at mid-northern latitudes every year, the ecliptic extends nearly vertically upward from the eastern horizon before dawn. That geometry favors the appearance of the faint zodiacal light in the eastern sky for about half an hour before dawn on moonless mornings. Zodiacal light is sunlight scattered by interplanetary particles that are concentrated in the plane of the solar system – the same type of material that produces meteor showers. It is more readily seen in areas free of urban light pollution. For observers at low latitudes, the ecliptic is nearly vertical all year round, making the light a frequent phenomenon. Sadly, observers north of 60°N latitude miss out.

If your location favours it, between now and Sunday’s full moon, look for a broad wedge of faint light extending upwards from the eastern horizon and centered on the ecliptic. It will be strongest in the lower third of the sky, below the twin stars Castor and Pollux. Try taking a long exposure photograph to capture it. Don’t confuse the zodiacal light with the Milky Way, which is positioned nearby in the southeastern sky. I posted a photo of it here.

The Planets

This week Mercury will replace Venus as the morning planet. Venus will be too close to the sun for observing until it begins to peek just above the southwestern horizon on December evenings.

Meanwhile, speedy Mercury will rise in the east about 90 minutes before the sun, allowing sharp-eyed early risers to see its dot shining low over the eastern horizon before about 7 am local time. Mercury will climb a little higher and farther from the sun every morning until Saturday, when the planet will reach a maximum angle of 18 degrees from the sun, and peak visibility, for the current morning apparition. In a telescope Mercury will exhibit a 50%-illuminated, waxing phase – but turn your optics away from the east before the sun rises). Mercury’s position above the nearly upright morning ecliptic will make this an excellent apparition for Northern Hemisphere observers, but a very poor one for those located south of the Equator, where the ecliptic, and Mercury’s orbit, will be more horizontal.

The medium-bright, creamy-coloured dot of Saturn will become visible in the lower part of the southeastern sky by 7:30 pm local time. Much brighter and whiter Jupiter will gleam a quarter of the sky away, to Saturn’s lower left. The ringed planet will be creeping slowly westward above the medium-bright stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) until late October. The planet and those stars will sink into the southwest after about 1 am local time. Since the planets always look their best in a telescope when they are highest in the sky, Saturn’s peak viewing time will arrive around 10 pm, when it will shine in the south – but you can enjoy less-than-perfect views from dusk onwards.

Even a small telescope will show Saturn’s subtly banded globe encircled by its glorious rings, which will become more edge-on to us every year until the spring of 2025. This year Saturn’s southern polar region has already extended well beyond the ring plane. See if you can see the Cassini Division, the narrow, dark gap that separates Saturn’s main inner ring from its bright outer one. Over the coming weeks, Saturn’s slide to the west of the anti-solar point will cause the planet’s globe to cast a widening wedge of dark shadow onto the rings where they emerge from behind the eastern limb of the planet. Where you find that shadow will depend upon how your telescope flips and/or mirrors the view. In a refractor or SCT telescope, it’s toward the upper right. In a Newtonian reflector, it will be toward lower right. An equatorial mount will rotate the scene, too. For best results, take long looks and wait for moments of perfect clarity.

A small telescope can also show several of Saturn’s moons – especially its largest, brightest moon, Titan! From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves all around the planet. Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn. During evening this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the right (or celestial west) of Saturn tonight (Sunday) to the upper left (or celestial northeast) of the planet next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope might flip that view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope?

This week, Jupiter’s extremely bright, white dot should clear the eastern rooftops as the sky darkens around 8 pm local time, and then spend the night blazing below the modest stars of western Pisces (the Fishes). Jupiter will climb highest, in the south, at 12:30 am local time, but it will look nice in any telescope by 9 pm. Early risers can spot the planet shining just above the western horizon before dawn.

Last week, Jupiter reached opposition for 2022, minimizing our distance from it and causing it to shine brightest in the sky and appearing largest in telescopes. As always, good binoculars will show Jupiter’s disk flanked by its row of four Galilean moons Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, which complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four of them, then one or more is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter – or lurking in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two moons are occulting one another. Any size of telescope will show Jupiter’s dark bands running parallel its equator.

Because Jupiter rotates once every 10 Earth-hours, anyone can use a good backyard telescope to watch the pale-looking Great Red Spot cross the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, the GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk on Monday, late Wednesday, and on Saturday evening, and also before dawn on Wednesday, Friday, and Sunday morning. If you have any coloured filters for your telescope, try enhancing the GRS with them.

The small, black shadows of Jupiter’s Galilean moons are visible through a good backyard telescope when they cross the planet’s disk. It happens more often around Jupiter’s opposition. Between 9:30 and 11:55 pm EDT on Saturday, observers in the Americas with telescopes can watch the small, black shadow of Europa cross the southern half of Jupiter’s disk. Io’s shadow will cross Jupiter’s equator on Sunday night, October 9 between 8:15 pm and 10:25 pm EDT. Don’t forget to adjust these quoted times into your own time zone.

Neptune is positioned in the sky between Jupiter and Saturn. This month, the distant planet’s faint, blue speck will be located a fist’s diameter to Jupiter’s upper right, and two finger widths to the upper right (or 2.9° to the celestial west-southwest) of a small star named 20 Piscium. Neptune is visible all night long in backyard telescopes. Good binoculars will show it, too – if your sky is very dark. Your best views will come after 8:30 pm local time, when the blue planet has risen higher. Still close to opposition for 2022, Neptune’s apparent disk size is 2.4 arc-seconds and its large moon Triton is still visible.

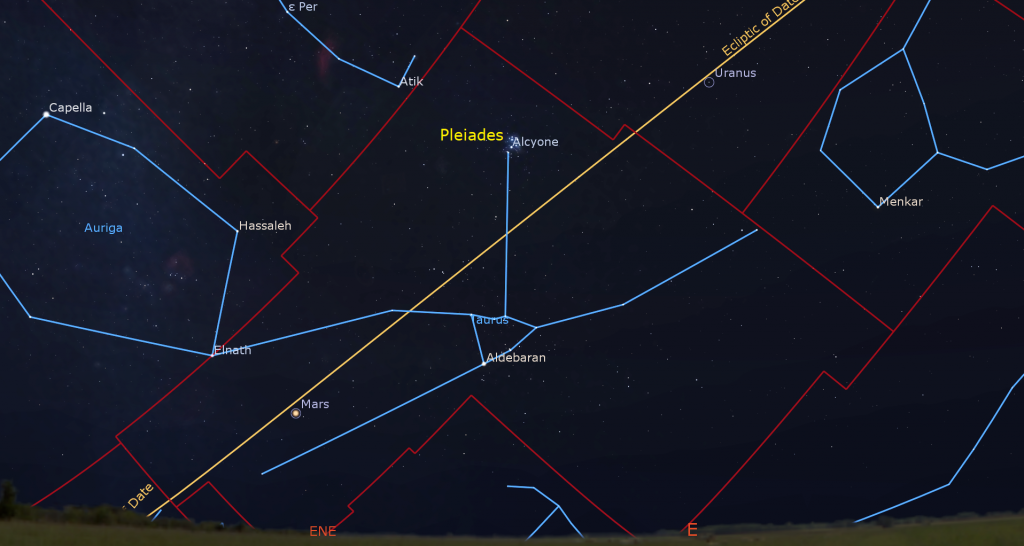

Uranus is within reach of binoculars in a dark sky, and in any telescope. The blue-green speck of the planet is located a generous fist’s width to the right (or 12° to the celestial southwest) of the Pleiades star cluster. Closer guideposts to Uranus are several medium-bright stars named Botein (or Delta Arietis), Al Butain II (or Rho Arietis), and Sigma Arietis which will appear several finger widths from Uranus. Those stars mark the feet of the Aries (the Ram). The magnitude 5.7 planet will be high enough for telescope-viewing, in the lower part of the eastern sky, by 10 pm local time this week.

This week, the medium-bright, reddish dot of Mars will rise above the east-northeastern horizon around 10 pm local time and will deliver nice views in a backyard telescope after 11 pm local time. In a telescope, Mars will show a growing, 88%-illuminated disk. Watch for the bright reddish star Aldebaran positioned 1.2 fist widths to Mars’ upper right (or celestial southwest). Mars will be brightening and growing larger as Earth’s faster orbit draws us closer to it over the coming months. We’re 115 million km (or 6.4 light-minutes) away from it this week.

Some Double Stars You Can See in Binoculars

Bright moonlight hides the fainter celestial objects, but stars tend to punch through it, especially when using binoculars and backyard telescopes. To add to the fun, check out double stars, two or more stars that are either orbiting close to one another (binary stars), or those which appear to sit near one another but are actually at vastly different distances from us (line of sight double stars). The pairs can look the same, like distant car headlights, or shine with contrasting brightness and colour. Here are a few suggestions to seek out in early October, moonlit or not.

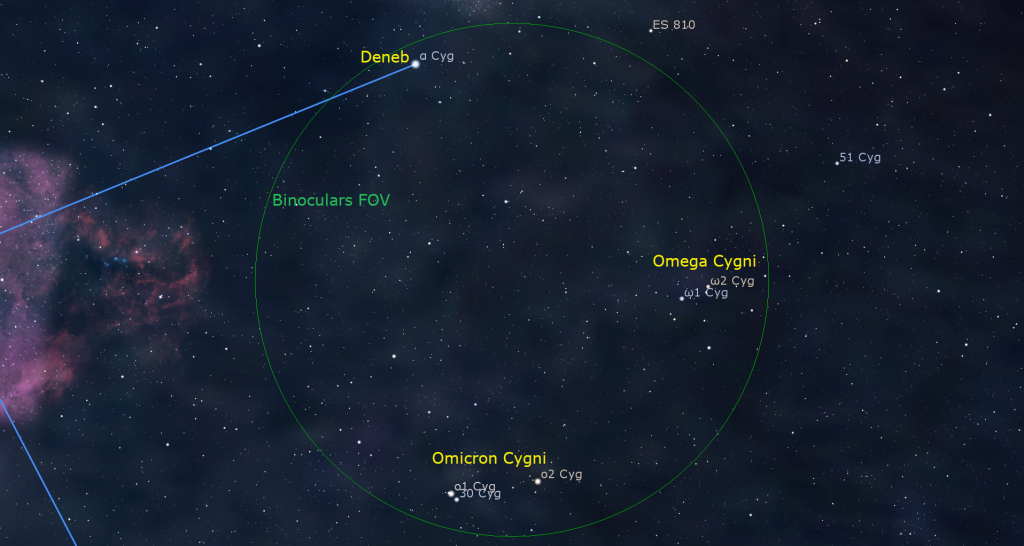

The very bright star Deneb in Cygnus (the Swan) shines nearly overhead on early-October evenings. When facing west in mid-evening, the sky just below (to the celestial northwest of) Deneb contains several double stars that can be split easily in binoculars. Warm-coloured Omicron1 and Omicron2 Cygni each shine at about magnitude 3.9 (i.e., they are visible without binoculars). They are separated by a generous finger’s width (or 1°). The lower (more southerly) star O1 is accompanied by a fainter white star named 30695 Cygni shining just 5 arc-minutes to its upper right (or northwest). Another fainter star shines closer in below it (to the south).

Located several finger widths to the upper right (or 3 degrees to the northeast) of Omicron, but still within the same binoculars field of view, look for blue-white star Omega1 Cygni shining a small distance to the lower left (or 19 arc-minutes to the south) of a cosy pair consisting of its mate, reddish Omega2 Cygni beside a white star named HIP 101206. (The prefix HIP comes from the Hipparchus star catalog.) A white, magnitude 5.7 star named 43 Cygni sparkles alone just to their right (or 40 arc-minutes to their west).

The bright star Enif, named from the Arabic phrase Al’anf, “the Nose”, indeed marks Pegasus, the Flying horse’s muzzle. The orange-tinted star shines two fist diameters to the right (or 20 degrees to the celestial west) of Markab, the southwestern corner star of Pegasus’ Great Square. Binoculars or any sized telescope will reveal a faint companion sitting close-in to Enif’s upper right (or northwest). Enif is a low-temperature, orange supergiant star located 670 light-years away from the sun. It is nearing the last stages of its life cycle, and is just at the lower mass limit for expiring in a supernova explosion. The bright globular star cluster named Messier 15 shares the binoculars with Enif. M15 is located only four finger widths to the upper right (or 4 degrees northwest) of Enif. It, too, can be seen in binoculars on a dark night.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

Taking advantage of the crescent moon in the sky this week, the RASC Toronto Centre astronomers will hold their free monthly City Sky Star Party in Bayview Village Park (steps from the Bayview subway station), starting after dusk on the first clear weeknight this week (Mon, Tue or Thu only). Check here for details, and check the banner on their website home page or Facebook page for the GO or NO-GO decision around 5 pm each day.

On Tuesday, October 4 from 7 to 8 pm EDT, the Dunlap Institute at University of Toronto will stream their popular Astro Trivia Night. The live, free event will feature lots of fun and prizes. Details are here.

Weather permitting, on Tuesday, October 4 from 7:30 to 9 pm, astronomers from RASC – Mississauga will hold a public star party at the Riverwood Conservancy, 4300 Riverwood Park Lane, Mississauga. Details and the ticket registration link are here.

On Wednesday evening, October 5 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will live stream their monthly Recreational Astronomy Night Meeting at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live. Talks include The Sky This Month, a new astrophotography camera, and more. Details are here.

RASC’s Public sessions at the David Dunlap Observatory will soon be resuming! In the meantime they are pleased to offer some virtual experiences instead in partnership with Richmond Hill. The modest fee supports RASC’s education and public outreach efforts at DDO. Only one registration per household is required. Prior to the start of the program, registrants will be emailed the virtual program link.

On Friday night, October 7 from 7:30 to 9 pm EDT, tune into the online DDO Up in the Sky. There will be a virtual tour of the DDO and live-streamed views from the DDO’s 74-Inch telescope (weather permitting). The deadline to register for this program is Wednesday October 5, 2022 at 3 pm. More information is here and the registration link is here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, October 11 at 3:30 pm EDT, when I’ll show you all the features in the Stellarium Mobile app! Plus, we’ll finish our Messier Objects observing certificate program. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.