The Morning Moon Helps Meteors Mount and the Eagle’s Sights, Evening Star Venus, and Shiny Saturn at Opposition near Jupiter!

The Ghost of the Moon planetary nebula aka NGC 6781 in Aquila, photographed by the European Southern Observatory 3.6-m Telescope at the La Silla Observatory in the Atacama Desert, Chile. The image spans 4.5 arc-minutes of sky, or 15% of the full moon. The object is an expanding sphere of gas – the outer shells of a dead star.

Hello, Mid-Summer Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of August 1st, 2021 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together!

This week, the waning moon will be travelling through the pre-dawn sky, leaving evening skies all around the world dark – for stargazers enjoying the sights in Aquila the Eagle and to see meteors from two concurrent showers. Saturn will reach peak visibility at opposition, near Jupiter, and Venus will blaze after sunset. And it’s Mid-Summer in the Northern Hemisphere. Read on for your Skylights!

Mid-Summer

Saturday, August 7 at 2:53 am EDT (or 06:53 GMT) will mark the mid-point of summer in 2021 – falling halfway between the June Solstice and the September Equinox. It is one of the four so-called cross-quarter days, which are the season midpoints following each solstice and equinox. Many pagan groups schedule Lammas or Lughasadh festivals around this time – to celebrate the early harvest. The term “lammas” refers to grain or bread. (Tolkien readers will notice that it resembles the word “lembas”, the Elven Waybread, from the same root.) The next cross-quarter day will occur in three months, at the beginning of November. That’s Samhain – but we celebrate it on the evening before – as Halloween!

The Earth passes aphelion in early July each year. Since Kepler’s Laws of Planetary Motion dictate that a planet orbits slower while at aphelion, summer in the Northern Hemisphere is several days longer than winter! Enjoy!

Two Meteor Showers

This week we will see the waning stages of the Southern Delta Aquariids meteor shower and the early stages of the Perseids meteor shower. Combined, you can expect to see about 4 good meteors per hour during the dark parts of the night, especially before the moon rises during the wee hours. I saw both a nice Southern Delta Aquariids meteor and a fantastic, long and bright Perseids meteor at around midnight on Friday!

The Southern Delta Aquariids will taper off until August 23. This shower, produced by debris dropped from periodic Comet 96P/Machholz, is best enjoyed from the southern tropics, where the shower’s radiant, in southern Aquarius, climbs higher in the sky. The spectacular Perseids started on July 17 and will continue until August 26. That shower, which can be enjoyed more from northern latitudes of Earth, will peak during mid-day in the Americas on Thursday, August 12.

Meteors from a particular shower appear to be travelling away from a radiant point in the constellation they are named for. During evening, Southern Delta Aquariids will be moving away from a spot low in the southeastern sky, while Perseids will streak from the northeastern sky. To increase your chances of seeing any meteors, find a dark location with lots of sky, preferably away from light polluted skies, and just look up with your unaided eyes.

Binoculars and telescopes are not useful for meteors because their fields of view are too narrow to fit the streaks of meteor light. Don’t watch the radiant. Any meteors near there will have very short trails because they are travelling towards you. Try not to look at your phone’s bright screen – it’ll ruin your night vision. And keep your eyes heavenward, even while you are chatting with companions. I’ll write more about Perseids meteors in the coming weeks. For now, good luck!

The Moon

The moon will be entirely absent from evening skies worldwide this week as it completes the final stages of its monthly orbit around Earth. That will deliver extra dark skies for viewing nebulas and star clusters, and the meteors from two showers that are currently underway.

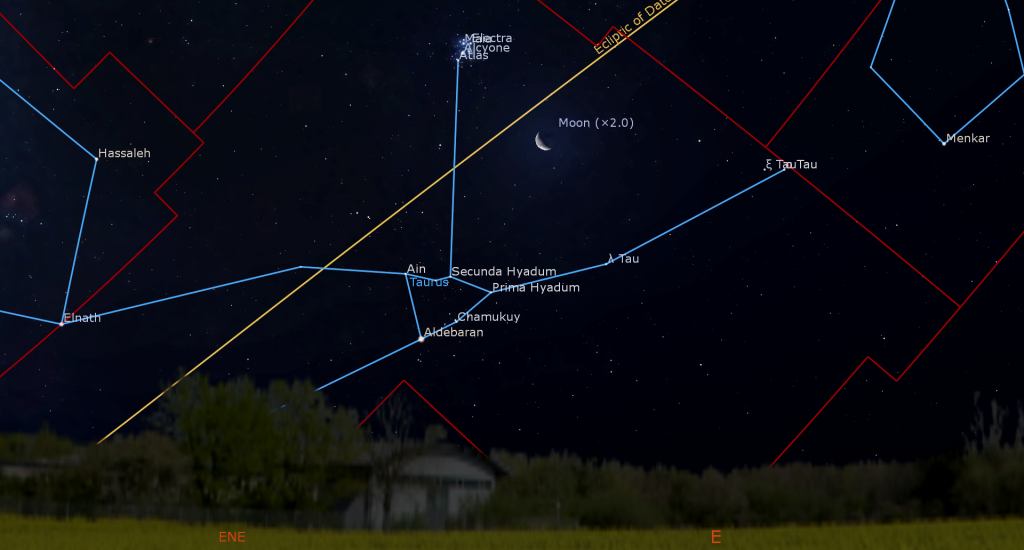

Tonight (Sunday) the moon will not rise until after 1 am local time. When it does, its waning crescent form will shine near the Pleiades star cluster in Taurus (the Bull) until dawn steals the stars. The moon will traverse the bull until Wednesday, spend Thursday and Friday in Gemini (the Twins), where it will show only a slim crescent. Those late-rising, waning crescent moons will also linger into the daytime morning sky – but they’ll become a challenge to see against the blue sky from mid-week onward.

You might catch a glimpse of the 1%-illuminated moon’s silver sliver sitting low over the east-northeastern horizon on Saturday before sunrise. The moon will reach its new phase on Sunday, August 8 at 9:50 am EDT (or 13:50 Greenwich Mean Time). While new, the moon is travelling between Earth and the sun. Since sunlight can only reach the far side of the moon, and the moon is in the same region of the sky as the sun, the moon becomes unobservable from anywhere on Earth for about a day (except during a solar eclipse).

The Planets

Mercury will join the western post-sunset sky this week, but it won’t be easy to spot until next week. Even though Mars will be positioned a short distance to the upper right (or celestial east) of the bright star Regulus, hazy skies near the west-northwestern horizon will make seeing the duo very difficult. (I tried unsuccessfully last Friday.) Mars won’t pass solar conjunction until early October, but the current extreme tilt of the ecliptic at sunset means that Mercury and Mars are setting too soon after the sun for the sky to darken and reveal them.

Not to worry! Venus is putting on a show every evening all around the world! Our neighbouring planet is shining at magnitude -3.9. That’s brighter than any star or planet – and even the International Space Station. While the ISS glides silently across sky, and distant aircraft flash their lights, Venus shines with a steady, unmoving point of light (except for the fact that it is slowly following the sun down).

Expect to see Venus sitting a generous fist’s diameter over the western horizon starting at about 9 pm local time (and earlier from more southerly locations). It will set by about 10 pm local time – just as the stars begin to come out. Venus will exhibit a smallish disk and have a somewhat squashed shape when viewed in a backyard telescope. That is because it’s only 81%-illuminated. Aim your telescope at Venus as soon as you can spot the planet in the sky (but ensure that the sun has completely disappeared first). That way, Venus will be higher and shining through less distorting atmosphere – giving you a clearer view.

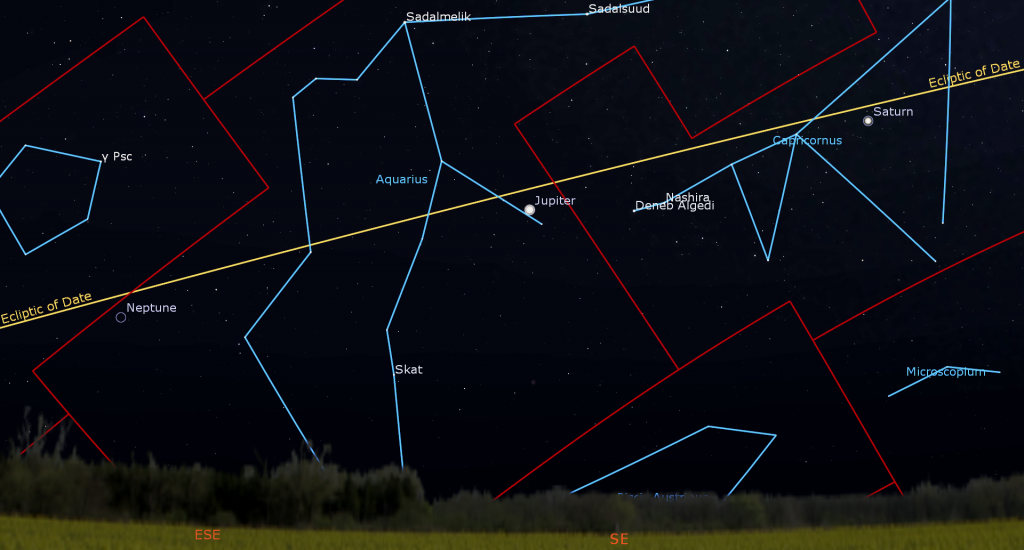

At about 8:30 and 9:30 pm local time, respectively, Saturn and Jupiter will rise over the east-southeastern horizon, and then remain visible all night long as they cross the sky. Tonight (Sunday) after midnight, Saturn will formally reach opposition and peak visibility for 2021! I wrote in detail about that last week here. During this week, Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from above (celestial northwest) of Saturn tonight to the lower left (celestial southeast) of the planet next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) Watch for the Milky Way and the teapot-shaped stars of Sagittarius (the Archer) sitting several fist diameters off to Saturn’s right (celestial west).

Sixteen times brighter Jupiter is positioned two fist diameters to Saturn’s left (or 19° to the celestial east), amidst the stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). It will reach opposition on August 20. Binoculars and small telescopes will show you Jupiter’s four largest moons, Io, Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede – collectively called the Galilean moons. They are always strung like beads along a straight line that passes through the planet, but their pattern varies from night to night.

For observers with good telescopes in the Eastern Time Zone the Great Red Spot (or GRS) will be visible crossing Jupiter late on Monday, Wednesday, and Saturday nights, also before dawn on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. From time to time, the small round black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. Io’s small shadow will be visible on Tuesday night, August 3 between 11:33 pm and 1:50 am EDT.

In the wee hours of Sunday, August 8 observers with telescopes in the Pacific Ocean and Eastern Asia regions can see two shadows on Jupiter together. At 12:45 am Hawaiian Standard Time or 10:45 GMT, Ganymede’s shadow will begin to follow the Great Red Spot across Jupiter. At 2:45 a.m. HST or 12:45 GMT, Europa’s smaller shadow will begin to cross. Ganymede’s shadow will move off the planet at 4:20 a.m. HST (14:20 GMT). Europa’s shadow will complete its transit an hour later, just as the Ganymede itself clears Jupiter’s limb. Observers on the west coast of North America can watch the second shadow appear as dawn breaks.

Dim, blue Neptune is located near the border between Aquarius and Pisces (the Fishes) – about 2 fist diameters to the left (or 23° to the celestial east) of Jupiter. It rises at about 10 pm local time and reaches peak visibility halfway up the southern sky before 4 am local time. Magnitude 5.8 Uranus is bright enough to see with binoculars and backyard telescopes, even near cities. This week it will rise at about midnight local time. It will be parked below Hamal and Sheratan, the two brightest stars in Aries (the Ram), all year long.

Aquila the Eagle

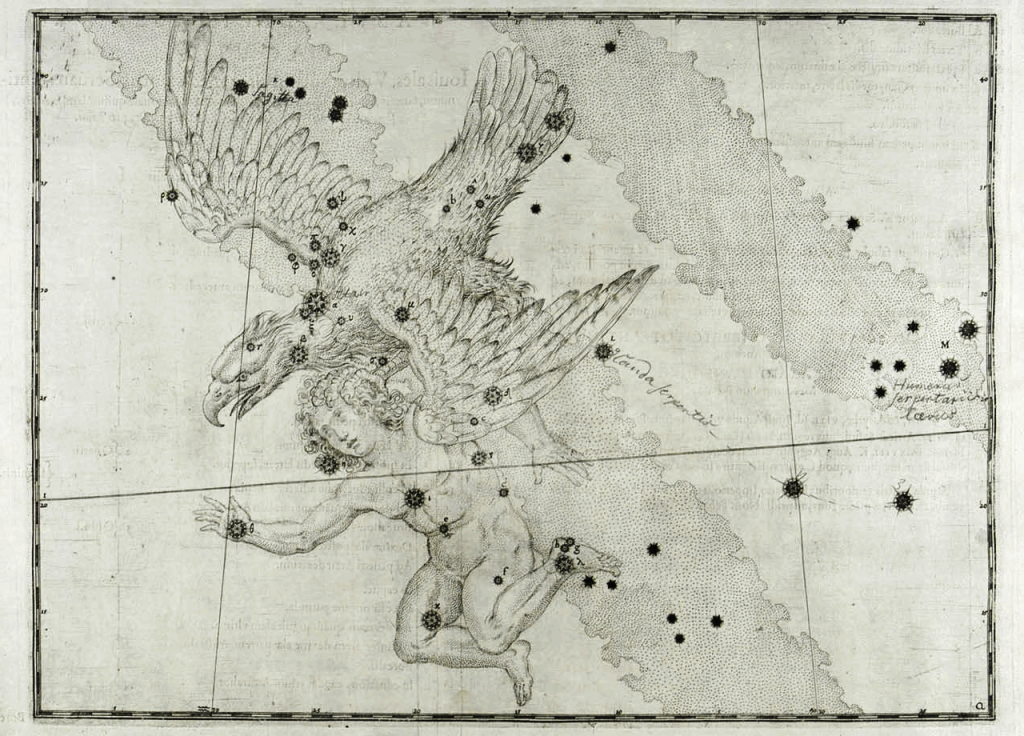

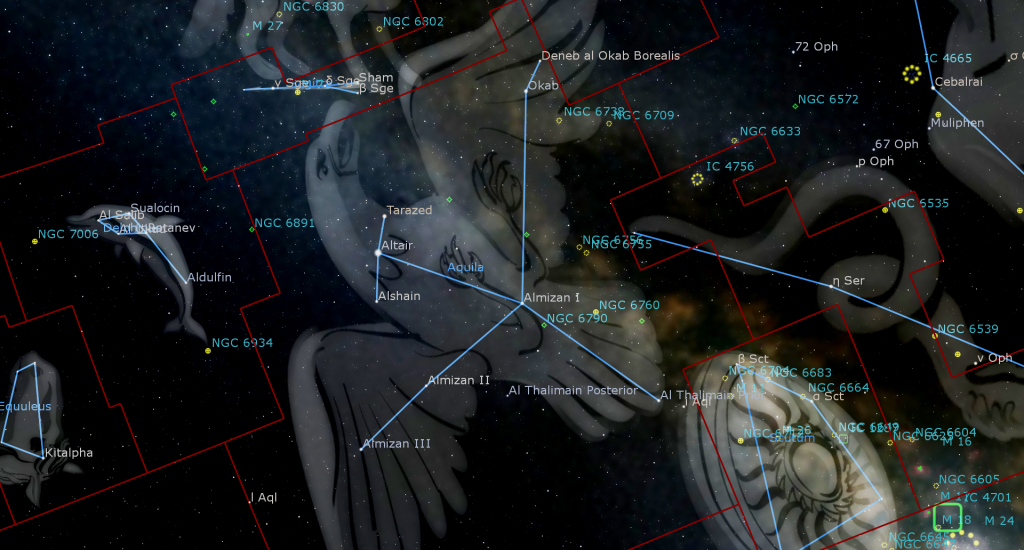

Look halfway up the southeastern sky on early August evenings, and you’ll easily spot the bright, white star Altair, sitting at the bottom corner of the Summer Triangle asterism. Altair is the brightest star in the venerable constellation of Aquila (the Eagle) and marks the great bird’s head. The eagle’s body and tail extend downwards to the right (or celestial southwest), more or less following the Milky Way. The wings extend upwards and downwards.

The great bird’s location close to the Milky Way has populated it with rich star fields. The celestial equator passes through it – allowing it to be seen easily by both Northern and Southern Hemisphere skywatchers. It is bordered by Scutum (the Shield), Serpens Cauda (the Snake’s Tail), and Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer) on the right (west), Sagittarius (the Archer) and Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) below (south), and cute little Delphinus (the Dolphin) and Sagitta (the Arrow) above (north). Hercules (the Hero) touches the eagle’s northern wingtip.In area, the bird spans three fist diameters square, or 30° by 30°, but the bright stars only subtend about 20° head to tail and wing tip to tip.

Aquila so clearly resembles a bird that many cultures saw the same pattern in its stars, including the Babylonians. In Greek mythology, it was the eagle that held Zeus’ thunderbolts. The Romans called it Vultur volans “the flying vulture”. The Hindus associated the stars with the half eagle-half human god Garuda.

Classic Chinese poetry told a well-known story about the Weaver Girl and the Cowherd, one of their four great folktales. In this tale, Zhī Nǚ (织女) the weaver girl was in love with Niú Láng(牛郎) the cowherd. To prevent their forbidden love, they were banished to the heavens. Zhi Nu, represented by the nearby bright star Vega, and Niu Lan, represented by Altair, were separated by the Silver River, or Milky Way. The two small stars which are visible just above and below Altair represent their children. As the story goes, each year on the 7th day of the 7th month in the Chinese lunisolar calendar, a flock of magpies would form a bridge, reuniting the lovers for one night only. In some years, the lunisolar calendar begins at the end of January, putting their 7th month into August. I suspect that those magpies were actually Perseids meteors, which travel parallel to the Milky Way every August.

Altair arises from the Arabic expression for “flying eagle”. The star itself is warm-white and spectral class A7Vn, about ten times larger than our sun, and a mere 17 light-years away, making it the twelfth brightest star in the night sky worldwide. Its 10-hour rotation rate is one of the fastest known, spinning so rapidly that the star has an oblate shape (wider at the equator than it is tall). In the sky, Altair is symmetrically flanked by two small stars named Alshain and Tarazed, or β and γ Aquilae, respectively. Because the three stars resemble a weighing balance, their names are derived from the Arabic phrase for one: “shahin-i tarazu”. The trio spans about three finger widths, or 5° of sky. Higher (more northerly) and brighter Tarazed is interesting. This orange, K3II-class star is 395 light-years-away. It is young, but highly evolved – already burning core helium, and it emits almost 3,000 times the luminosity of our sun. It also emits an abundance of X-rays! Magnitude 3.7 Alshain is located two finger widths below (or 2.7° south-southeast of) Altair. This 44.7 light-years-away, yellowish G8IV-class star has also exhausted its core hydrogen and is evolving into a giant.

The rest of Aquila’s main stars are dimmer, but nonetheless visible to unaided eyes under a dark sky. Almost a fist’s diameter to the lower right (southwest) of Altair is the star Delta Aquilae, or Almizan I, representing the body. The wings, each a generous fist’s diameter (11°) in length, extend up and down from that star. The upper wingtip is marked by the white star Deneb al Okab Australis, or Zeta Aquilae, and a slightly dimmer star named Deneb al Okab Borealis. Those names mean the southern and northern “tail of the eagle”. (The reference to the tail arose by using a different interpretation of the star patterns.)

The lower wing is formed by two widely spaced stars. Almizan II is at the elbow, and Almizan III is at the wingtip. (Some apps use the designations Eta Aquilae and Theta Aquilae.) The eagle’s tail is marked by a pair of small stars separated by a finger’s width. The brighter tail star is named Al Thalimain Prior “the front ostrich”. The Pioneer 11 spacecraft, launched in 1973, is coasting towards this star, with an arrival time of about 4 million years! The “rear ostrich” is the star Iota Aquilae, which sits about midway between the tail and the lower wingtip. These manes appear to be left-over from a previous version of the constellation.

Almizan II, the lower elbow star, is a Cepheid variable star that doubles in visible brightness (from magnitude 3.5 to 4.4) on a 7.18 day cycle. At maximum, it shines almost as brightly as Lambda Aquilae, the tail of the eagle. At minimum, it’s as faint as Iota Aql, the “rear ostrich”. Try comparing the brightness of those three stars on different nights and see the difference!

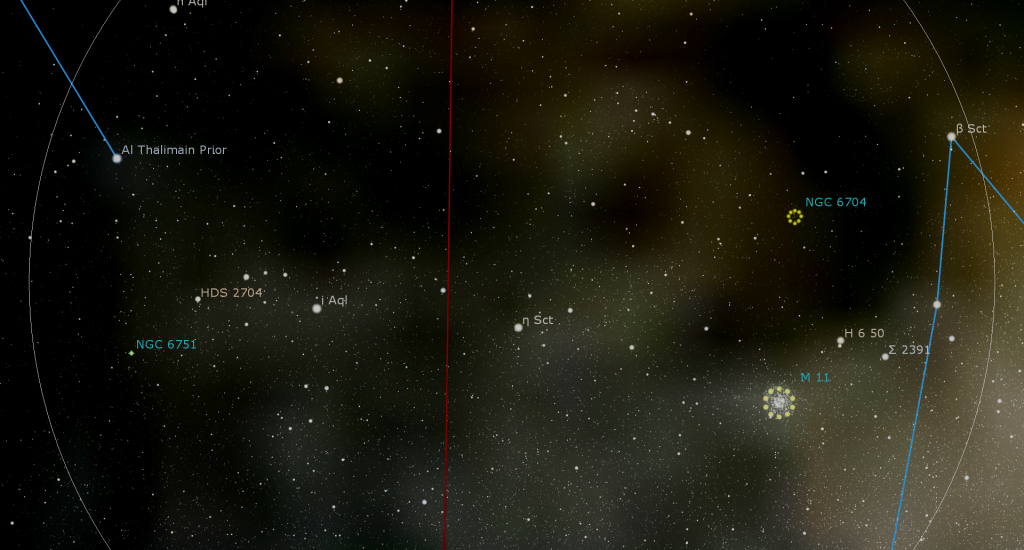

Sweep your binoculars though the area around and above Aquila to see an abundance of stars from the nearby galactic plane, and a dark dust lane. About three finger widths to the right (or 4° WSW) of the eagle’s tail, in the next-door constellation Scutum (the Shield), you’ll easily spot another avian object – the Wild Duck Cluster or Messier 11 – a famous bright open cluster.

Within a binoculars’ field of view to the lower right of Okab are two more open star clusters, NGC 6738 and NGC 6709. Another binoculars’ field diameter to their lower right is a bigger, brighter cluster called the Tweedledee Cluster, or the Graff’s Cluster.

If you have a large telescope, or if you are observing Aquila under dark, rural skies, aim your telescope a few finger widths along the eagle’s upper wing and look at the Ghost of the Moon planetary nebula or NGC 6781. It’s not very bright, but it’s huge – more than twice as large as Jupiter!

Let me know if enjoy the Eagle!

A Summer Triangle Tour

If you missed last week’s tour of the sky around the Summer Triangle asterism, which shines high in the eastern sky in early August, I posted it here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory YouTube channel.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

On Wednesday evening, August 4 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will live stream their monthly Recreational Astronomy Night Meeting at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live. Talks include the Sky This Month, appreciating and observing the moon, and how the ancients weighed the Earth. Details are here.

On Thursday, August 5 from 7 to 8 pm EDT, the Dunlap Institute at University of Toronto will host another online Astro Trivia Night. The live free event will feature lots of fun and prizes. Watch it here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National will return on Tuesday, August 17 with a Gas Giant Planets Special! You can find more details, and the schedule of future sessions, here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!