Venus Kisses Jupiter at Sunset, a Waxing Moon in Evening, and Eyeing Mare Imbrium!

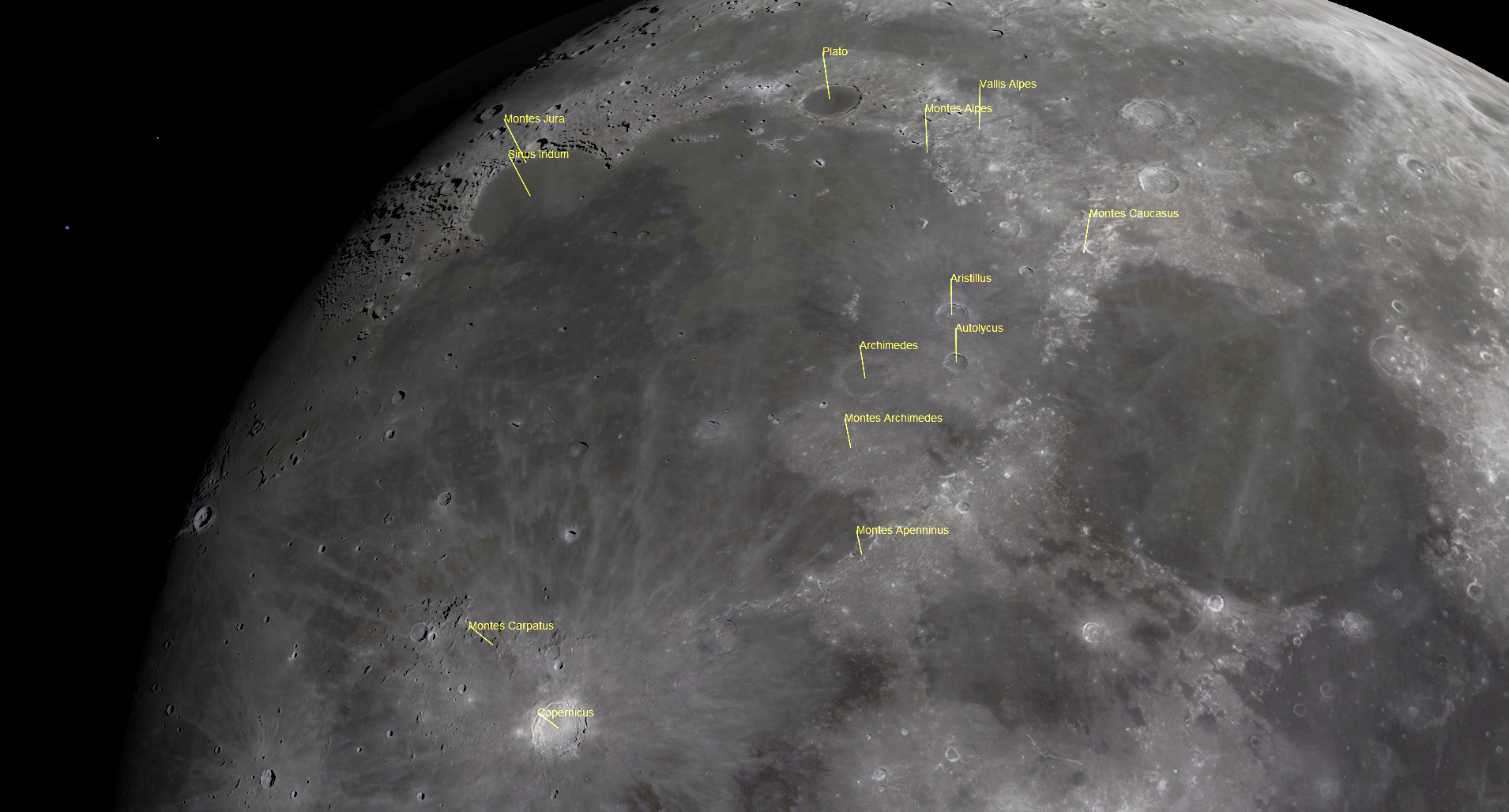

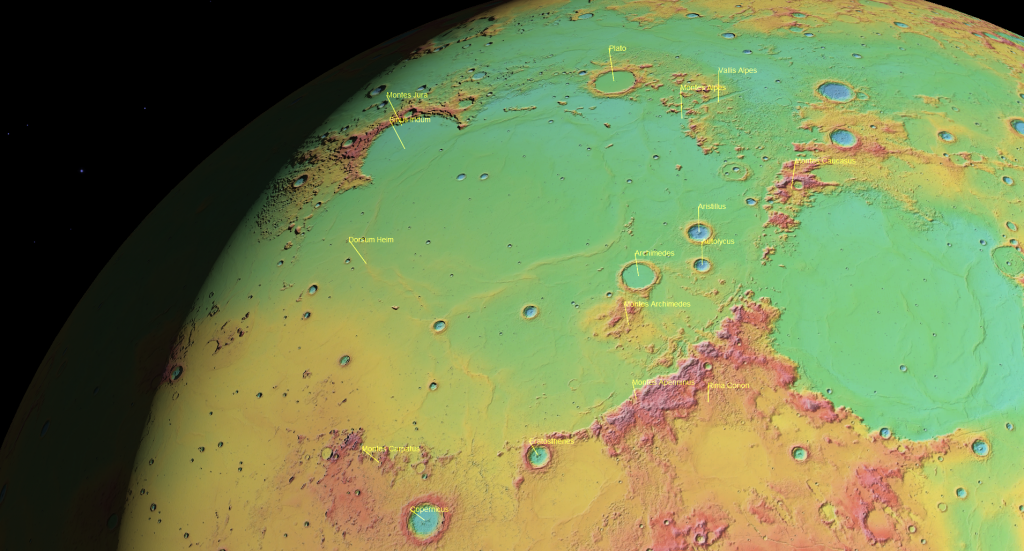

A labelled map of the Mare Imbrium region of the moon, shown for 8 pm on Friday, March 3. On the previous evenings, the pole-to-pole lunar terminator will sweep across Mare Imbrium, highlighting its features. (Starry Night Pro 8)

Hello, Fellow Moongazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of February 26th, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will dominate the evening sky worldwide this week as it waxes past first quarter. I highlight one of the moon’s biggest and most easy to see features, Mare Imbrium. Brilliant Venus will kiss bright Jupiter on Wednesday, and the moon will pass Mars shining on high in evening. Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon

The moon will dominate the evening sky worldwide this week, so let’s take advantage of the opportunity to soak in its spectacular sights. Better yet, Earth’s natural night light will be visible during the afternoon daylight hours – and Daylight Saving Time doesn’t start until March 12 – so for Northern Hemisphere residents, the moon can be enjoyed by the youngest of stargazers well before bedtime. Or, spend some moon-gazing time outside and then head indoors for some hot cocoa and a movie!

I’ll share what the moon will be up to this week and then take you on a tour of one of its most interesting features.

Today (Sunday) the half-illuminated moon will rise before noon in your local time zone and then climb the eastern half of the sky until late afternoon. You can safely view the daytime moon in binoculars and a backyard telescope if you take care not to swing your optics near the sun. (Parental supervision is a must here.) To make the moon stand out against the blue sky, use any polarized filter. You can wear a pair of 3D glasses and tilt your head to find the angle where the sky darkens the most. Half of a variable moon filter screwed onto your telescope eyepiece can be used instead. Just loosen the thumbscrews and turn the eyepiece until the same effect is achieved.

Once the sun sets on Sunday, the moon will be accompanied by the bright little Pleiades Star Cluster to its right (celestial northwest) and the fainter stars of the larger Hyades Cluster to its left. The Hyades form the triangular face of Taurus (the Bull). The bright orange-tinted star Aldebaran occupies one corner of the Hyades, serving to mark the eye of the bull. The slightly brighter and reddish dot of Mars will shine about 1.3 fist diameters to the upper left of the moon.

The lunar terminator, the pole-to-pole line that divides the lit and dark hemispheres of the moon, will be nearly straight. Sunlight that strikes the moon along that line is nearly horizontal, casting spectacular shadows to the west of even the smallest elevated feature. For someone standing along the terminator, the sun will be just rising over the moon’s eastern horizon. With no atmosphere to scatter away the blue light, they won’t see a red sunrise, though.

Use your optics to scan along the terminator, looking for bright peaks rising above a sea of black – or deep crater floors still in full shadow while their rims are bathed in light. During this portion of the 29.5 day lunar month, the terminator creeps continuously west, providing us with new views hour after hour and night after night.

The moon will complete the first quarter of its orbit around Earth at 4:06 am EST, 1:06 am PST, or 08:06 Greenwich Mean Time on Monday, February 27. At first quarter the relative positions of the Earth, sun, and moon cause Earthlings worldwide to see our natural satellite half-illuminated – on its eastern side.

After dusk on Monday evening, the waxing gibbous moon (i.e., now more than half-illuminated) will be shining high in the southern sky. In easterly time zones Mars will be poised just two finger widths to the moon’s left (or celestial east) – close enough for them to share the view in binoculars. As the hours pass, the moon’s eastward orbital motion will carry it far closer to the red planet. Around 11 pm PST, (which converts to 1 am EST and 05:00 GMT on Tuesday) the moon will pass less than its own diameter to the north of Mars, allowing them to share the view in a telescope. Skywatchers located in Iceland north of Reykjavik and the Faroe Islands can see the moon cross in front of (or occult) Mars around 05:00 GMT.

On Tuesday night the moon will pass into Gemini (the Twins). On Thursday night, the waxing gibbous moon will shine binoculars-close to Gemini’s brightest star Pollux. After dusk, the moon will be positioned two finger widths to the right (or 2 degrees to the celestial southwest) of Pollux in the eastern sky. Pollux’ sibling, the bright double star Castor, will twinkle above them. As the night wears on, the diurnal rotation of the sky will swing Pollux and Castor to the moon’s right. Because the moon will also be sliding eastward in its orbit, early risers on Friday morning will see the trio forming a horizontal line above the west-northwestern horizon.

After dusk on Friday, the large open star cluster known as The Beehive (or Messier 44) will be positioned several finger widths to the lower right (or 4 degrees to the celestial south) of the bright gibbous moon. Encounters between M44 and the moon or planets occur frequently because the cluster is located only one degree away from the ecliptic in the constellation of Cancer (the Crab). The moon and the Beehive will share the field of view of binoculars, but the moon’s brilliance will overwhelm the cluster’s stars. To see more of the “bees”, hide the moon just outside your optics’ field of view. During the night, the diurnal rotation of the sky will shift the Beehive to the moon’s lower left.

The nearly full moon will spend the coming weekend visiting the stars of Leo (the Lion). Due to the moon’s orbital inclination and orbital ellipticity, it nods up-and-down and sways left-to-right by up to 7 degrees while keeping the same hemisphere pointed towards Earth. Over time, this lunar libration effect lets us see 59% of the moon’s total surface without leaving the Earth. For several nights surrounding Saturday, March 4, the moon’s brightly lit southeastern limb will be rotated toward Earth, revealing a collection of dark patches that can be seen in a backyard telescope. Together they comprise Mare Australe, the Southern Sea. The northern and southern boundaries of the mare are dominated by the isolated dark ovals of the craters Oken and Hanno, respectively. Between them, look for the similarly-toned craters Brisbane Z and E and the large, lighter grey crater Lyot. In evening, Mare Australe will be on the moon’s right-hand edge. Around midnight and beyond, the mare will be rotated toward the bottom of the moon.

Eying Mare Imbrium

The northwestern sector of the moon’s Earth-facing side is dominated by a huge, circular grey area known as Mare Imbrium, the Sea of Showers. The moon’s maria (plural for the Latin word mare, “sea”) were produced when large objects collided with the moon and excavated bowl-shaped depressions or basins. These were later filled in by molten basaltic lava seeping from the moon’s interior. Since the moon has a differentiated structure, its original surface was primarily less dense, light-coloured aluminum rich rocks named anorthosite, while the interior contained heavier, darker, iron-rich rock called basalt.

Uranium-lead isotopic dating methods applied to samples of Imbrium rock returned by Apollo 15 astronauts, who visited the basin’s edge, and other robotic missions yield estimates of 3.922 billion years for the age of the original impact – placing it in the late heavy bombardment era of 4.1 to 3.8 billion years ago. Material ejected during the Imbrium impact has been spread widely across the moon’s surface. The flooding lavas that filled the basin 500 million years later has produced a smoother, less-cratered surface. But lunar maria have other interesting features, as we’ll see below.

Mare Imbrium is 1,145 km wide and very circular in form, making it the largest and youngest of the impact basins on the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere. To the unaided eye, its eastern side (on the right when viewing the moon from the Northern Hemisphere of Earth) touches smaller Mare Serenitatis. Three impressive, curved mountain chains surround the eastern rim of Mare Imbrium. Those mountains are actually segments of the original basin’s rim.

The most northerly arc of mountains is the Lunar Alps, or Montes Alpes. Their peaks reach up to 2,400 metres above the moon’s average surface. Use binoculars or a telescope to look for a gash cutting through them called the Alpine Valley, or Vallis Alpes. It’s a rift valley, up to 10 km wide, where the moon’s crust has dropped due to faulting. To the lower right (lunar southeast) of the Alps are the Caucasus Mountains, or Montes Caucasus. This shorter, but tall (up to 6,000 metres tall) mountain range disappears under a lava-flooded zone connecting Mare Imbrium with Mare Serenitatis. The mountains resume along the southeastern edge of Mare Imbrium as the lengthy Apennine Mountains, or Montes Apenninus. They, too, peter out near the prominent crater Eratosthenes, and the larger crater Copernicus beyond it. The Apennines have several large peaks reaching 5,000 metres high and are cut through by several obvious radiating lineations.

All three of those ranges tend to have scarps up to 5 km high on the interior side of Imbrium, and then sloping ramparts on the exterior. That was caused when the flat crust layers around the basin wall were pushed radially away from the impact site, uplifting a ring of crust around the basin and also depositing ejected material as a blanket.

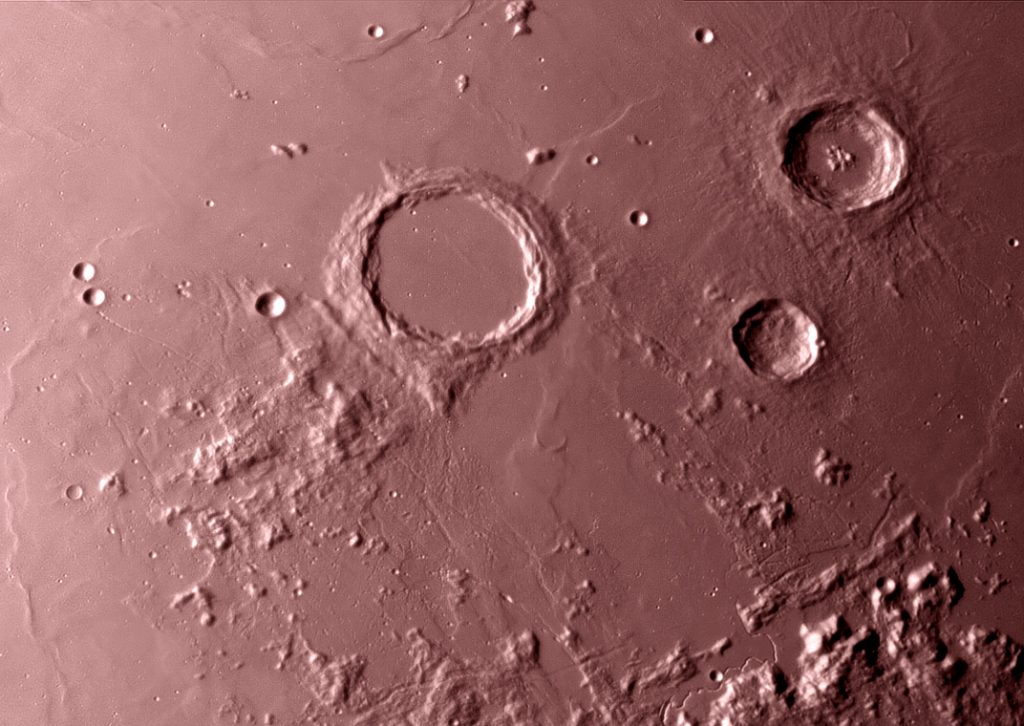

A large crater named Archimedes is prominent just inside the Apennine Mountains. Its floor isn’t as deep as one would expect, nor does it have a central peak as many large craters do. It was likely formed after the basin was formed, but before the lava flooding – so it was partially submerged by basalts, inside and out. The colour of Mare Imbrium itself is much lighter between the Apennines and Archimedes. Planetary scientists theorize that rubble on the inside of the basin was piled high enough not to be covered when the lavas flowed. The area is known as Archimedes Mountains or the Apennine Bench.

More bright coverage surrounds the two smaller craters near Archimedes. Aristillus, the larger, more northerly crater and Autolycus to the south were formed by impacts into the bright rubble area long after the basalts filled Imbrium. Each of them is surrounded by a blanket of brighter ejecta that shows well in binoculars or a backyard telescope.

Another mountain range named the Carpathian Mountains, or Montes Carpatus, outlines a portion of the basin’s southern edge. They are located just north of the big crater Copernicus. This range is much less well defined.

The southwestern edge of Mare Imbrium blends into the larger Oceanus Procellarum region. But the ring-like nature of Mare Imbrium can still be seen by looking at a series of wrinkle ridges that curve almost continuously around the inside of the mare. The best way to see them is to use a telescope when the terminator is passing across the basin.

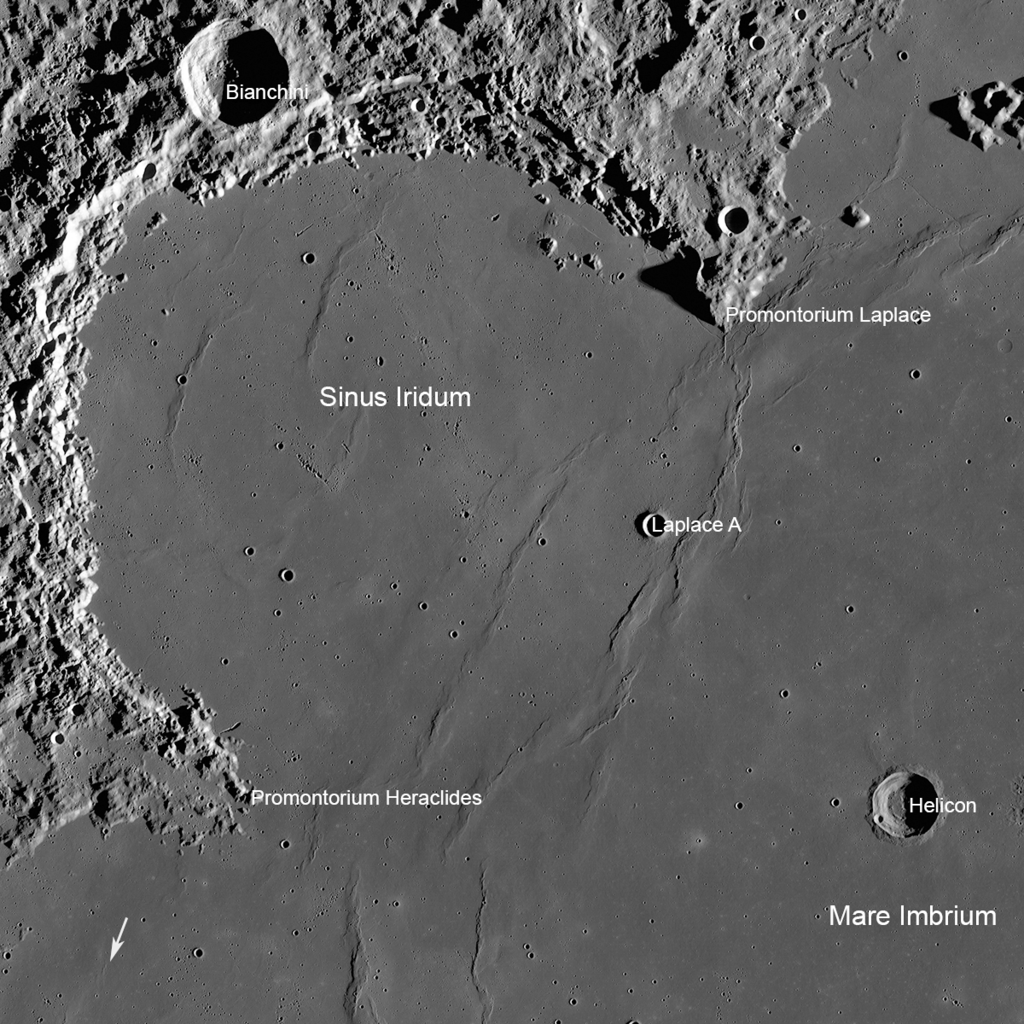

The northwestern edge of Mare Imbrium is dominated by the curved bay shape of Sinus Iridum “the Bay of Rainbows”. That semi-circular, 249 km diameter feature is a large impact crater that was later flooded by the same basalts that filled the much larger Mare Imbrium to its east – forming a rounded “handle” on the western edge of the mare. An effect called the “Golden Handle” is produced when low-angled sunlight strikes the prominent Montes Jura mountain range surrounding Sinus Iridum on the north and west – the former crater rim. Sinus Iridum is almost craterless, but hosts its own set of northeast-oriented wrinkle ridges.

I’ll share more information about this fascinating part of the moon in a future post. For, now take advantage of the fact that the terminator will sweep across Mare Imbrium this week from Monday to Friday.

The Planets

Over the next few months the planets Neptune, Jupiter, Uranus, and Mars will disappear from the evening sky. One after the other, they’ll be carried lower in the west after sunset and disappear into the evening twilight. Not long after that they’ll pass the sun in solar conjunction and later gradually reappear in the eastern pre-dawn sky. Faint Neptune is already too faint and too low for viewing after sunset.

Once Jupiter disappears around mid-March, Uranus in early April, and Mars in late June, only Venus will remain. Evening planet viewing will gradually return from July 1 onward, when Saturn will start to rise before midnight again – but Venus will be exiting the scene around then, too. Fortunately, speedy Mercury bounces into sight for a week or two, alternating between post-sunset and pre-dawn, about six times per year. These lengthy periods without planets make it helpful to know what else to view in your telescope! I’ll help you with that.

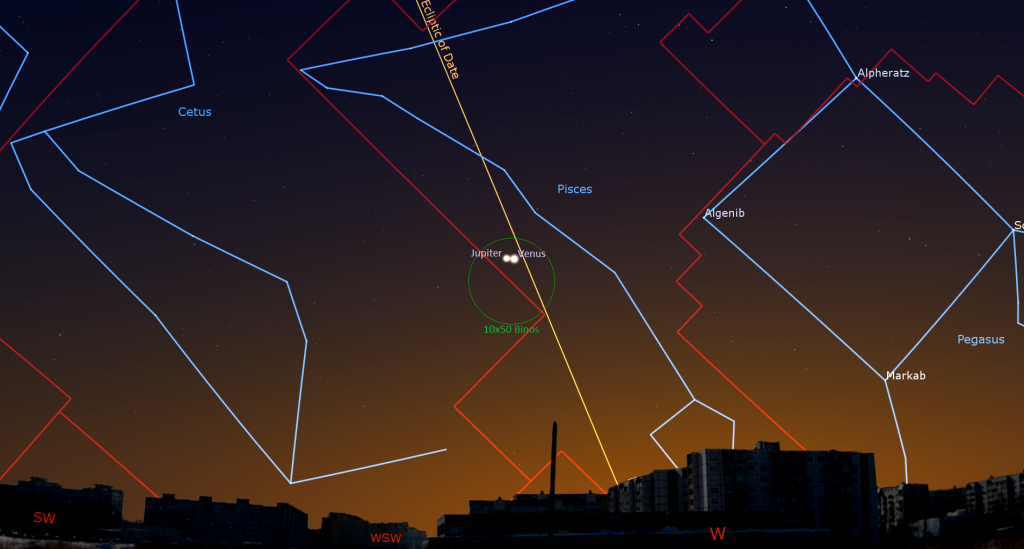

Not long after the sky begins to darken after sunset this week the bright dots of Venus and Jupiter will appear near one another in the lower part of the western sky. Tonight (Sunday) Jupiter will shine a short distance above five times brighter Venus. Jupiter is being carried downward (sunward) with the background stars while Venus’ eastward orbital motion is moving it upward in the opposite direction. They’ll converge from Sunday to Tuesday, kiss in a spectacular close conjunction on Wednesday, March 1, and then start to separate again as Jupiter drops lower.

Observers in the Americas will see magnitude -2.1 Jupiter positioned just 0.5 degrees to the left (or celestial south) of Venus on Wednesday – allowing them to share the view in a backyard telescope. Jupiter will be four times farther away than Venus but almost three times larger. Skywatchers in the Pacific Ocean region can see them even closer together a few hours later than North America does. In case of clouds, the two planets will still be telescope-close on Thursday evening.

This week Venus will set around 8:45 pm local time. Viewed in a telescope, Venus will display a slowly waning, 86%-illuminated disk. To see its shape most clearly in a telescope, look at Venus and Jupiter as soon as you can find them, when they will be higher and shining through less intervening air. Like the moon, you can see Jupiter and Venus in the daytime if you know where to look – and thus see them while they are even higher in the sky. But take care to avoid aiming anything near the sun.

Like Venus, Jupiter will set in the west around 8:45 pm local time this week. Binoculars should be able to show Jupiter’s disk bracketed by its line of four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. Three moons will clump together on Monday evening.

For another week or two, even a small, but decent quality telescope will show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in early evening on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, and a little later on Sunday, Wednesday, and Friday evening. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

The weak, magnitude 5.8 dot of blue-green Uranus will continue to be located nearly halfway from Mars towards Jupiter and Venus. You can also search a generous fist’s width to the left (or 12.5° to the celestial southeast) of Hamal, the brightest star in Aries (the Ram). Closer guideposts to Uranus are several medium-bright stars, including Al Butain II (or Rho Arietis), 40 Arietis, Omicron Arietis, and Sigma Arietis, which will surround the planet within the same binoculars field of view. Those faint stars mark the hooves of the Ram. Uranus will be ideally placed for telescope-viewing, high in the southern sky, immediately after dusk this week. It will become too low for viewing after about 10:15 pm.

Mars continues to be easy to see high in the sky after dusk each night. Although it continues to fade in brightness and become smaller in telescopes as Earth increases its distance from the red planet, you can still use a high magnification eyepiece to see the largest dark markings on its ochre 8.3 arc-seconds-wide disk. If you have coloured filters for your telescope, see if the blue, orange, or red one improves the view.

Mars will be positioned at its highest point (and its absolute best telescope viewing time) in the southern sky around 7 pm local time. Look for its reddish dot shining between the horns of Taurus (the Bull) and a fist’s width to the upper left (or celestial northeast) of the bright, reddish star Aldebaran, which marks the angry eye of the beast. The Pleiades star cluster will be twinkling off to Mars’ right (celestial west). Over the coming weeks, you’ll be able to see Mars moving eastward each night, farther from Aldebaran and the Pleiades and towards Gemini (the Twins). Mars will descend the western sky through the night and set during the wee hours. Don’t forget to catch the half-moon shining right beside Mars on Monday night.

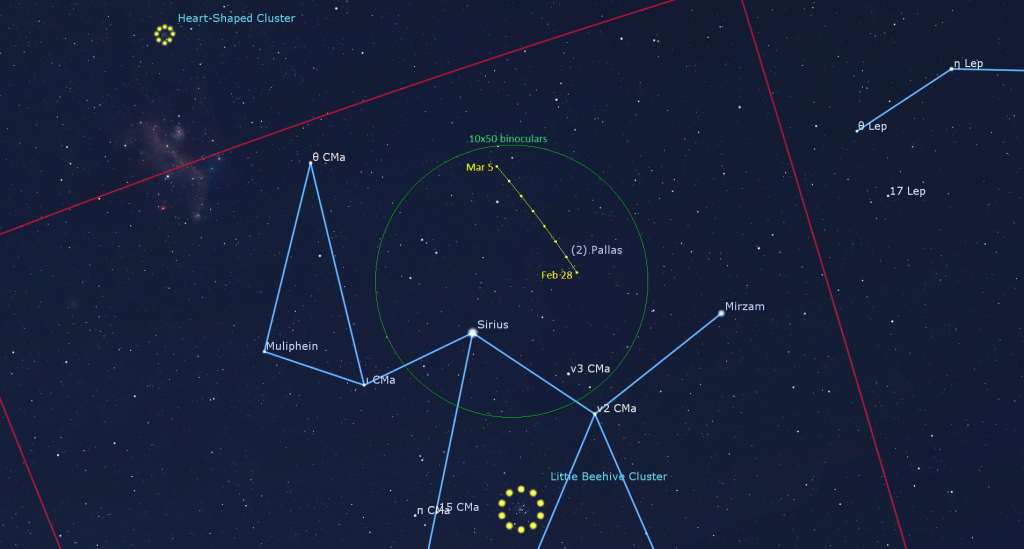

The main belt asteroid designated (2) Pallas is currently shining with a visual magnitude of 7.9, which is within reach of binoculars and backyard telescope. Pallas will still be situated low in the southern sky after dusk, in western Canis Major (the Big Dog) near the night sky’s brightest star Sirius. It’s also near the bright Little Beaver Cluster (Messier 41).

An Eye on Orion

If you missed last week’s tour of the eye-catching constellation of Orion (the Hunter) and his famous three-starred belt, I posted it with sky charts and photos of some of the objects here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras (weather permitting), answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. On Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Wednesday evening, March 1 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will host their in-person monthly Recreational Astronomy Night Meeting in the Gemini East Room at the Ontario Science Centre. The meeting will also be live streamed at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live. Talks include The Sky This Month, astrophotography, and a new app-controlled telescope mount. Details are here.

This winter, spend a Sunday afternoon in the other dome at the David Dunlap Observatory! On Sunday, March 5, from 1 to 2:30 pm, join me in my Starlab Digital Planetarium for an interactive journey through the Universe at DDO. We’ll tour the night sky and see close-up views of galaxies, nebulas, and star clusters, view our Solar System’s planets and alien exo-planets, land on the moon, Mars – or the Sun, travel home to Earth from the edge of the Universe, hear indigenous starlore, and watch immersive fulldome movies! Ask me your burning questions, and see the answers in a planetarium setting – or sit back and soak it all in. More information is here and the registration link is here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcast with RASC National returns on Tuesday, February 28 at 3:30 pm EST. With the moon waxing in the evening sky, this is the perfect time to watch the terminator slide across the giant and ancient lunar basin of Mare Imbrium. We’ll highlight the basin’s geology and showcase Imbrium sights to see with unaided eyes, through binoculars, and in telescopes of any size. Then we’ll highlight the next batch of RASC’s Finest NGC objects. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!