Venus Kisses Saturn on Lunisolar New Year, Coming Comet E3, the Evening Moon Encounters Planets and then Shows Eastern Seas!

This amazing image of Comet C/2022 E3 (ZTF) shows the narrow blue ion tail and the broad dusty debris tail. Celestial north is up. It was imaged by Michael Jäger of Austria on January 20, 2023 at 1:40 UT. He posted it on Twitter, where you can find a fantastic animated version. Follow him at @Komet123Jager

Happy Lunisolar New Year, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of January 22nd, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

Let’s look at the astronomy and culture of the lunisolar new year. The moon will return to shine in the evening sky worldwide this week, so dust off your telescopes and binoculars. Your unaided eyes can see it visit the bright planets during the week and then turn its eastern cheek toward Earth on the weekend. Meanwhile, the comets C/2022 E3 (ZTF) and C/2020 V2 (ZTF) will both be observable in evening, the former in binoculars and maybe with your unaided eyes! Mercury will be easy to see before sunrise, Venus will kiss Saturn in a very close conjunction on Sunday, and Jupiter and Mars will dazzle in evening. Read on for your Skylights!

Lunar New Year and Lunisolar Calendars

“Xīn Nián Kuài Lè!” 新年快乐! It’s Lunar New Year for many Asian countries, including China, Korea, and Vietnam! I touched upon the topic last week. Let’s dive a little deeper.

Unlike our Western Gregorian calendar, a lunisolar calendar uses the 29.53-day cycle of the moon’s phases to define the months of the year – usually starting each month when the new moon phase occurs, or on the day when the young crescent moon is first glimpsed after sunset. The placement of those months is anchored to a solstice or equinox. Since solstices and equinoxes are Earth-Sun phenomena, and completely independent of the moon’s phases, lunisolar calendars drift compared to our Gregorian system. And, because the moon runs through its cycle 12.37 times per year, every second or third lunisolar year requires an extra 13th intercalary or “leap” month.

Several world cultures (Hindu, Hebrew) still follow a lunisolar calendar, while Muslims follow a pure lunar calendar. The Chinese lunisolar calendar places the December solstice into the eleventh month – causing the first month of the subsequent year to begin about two months later – on the new moon that occurs somewhere between January 21 and February 20 on our calendar. Most of the time, that moon phase lands in early February.

When the moon officially reaches its new moon phase on Saturday, January 21, 2023 at 3:53 pm EST, 12:53 pm PST, or 20:53 Greenwich Mean Time, it will trigger the Lunar New Year observed in many Asian countries. Since that new moon also happens on Sunday, Beijing-time – that will be the first day of Chinese New Year holiday celebrations worldwide. It is also the first day of the Spring Festival 春节, or Chūn Jié (“CHWUN-jee-EH”), which ends with the Lantern Festival on the full moon two weeks later. Asian families will kick things off early by celebrating New Year’s Eve, Saturday night, with a meal together. In Vietnam, the new year is called Tết, short for tết nguyên đán, meaning “Festival of the First Morning of the First Day”. Koreans celebrate Seolla, from Eumnyeok Seollal “lunar new year”. Japan switched to our western Gregorian new year in 1873.

Happy Year of the Rabbit! The Chinese use a zodiac system – but their version doesn’t relate to the sun’s journey along the ecliptic, or even to any of the animal constellations. Instead, their zodiac preserves the sense of that word from the Ancient Greek expression zōdiakòs kýklos (ζῳδιακός κύκλος), “cycle of small animals”. They assign an animal and its attributes to each year in a repeating 12-year cycle. That interval may have arisen from the 11.85-year orbital period of Jupiter!

The order of the animals is said to have been determined by a great race to become the guards of the Jade Emperor – with their rank determined by the order in which the animals arrived at the finish line – the palace gates. The race involved both running and swimming. The mighty ox was a shoe-in to win the race. But the rat woke up early on race-day and took the lead. Arriving at the river, he feared to cross it. When the ox arrived, the rat jumped onto the gentle ox’s back and hitched a ride across. Upon reaching the opposite shore, the little rascal jumped off of the tired ox and raced ahead to win the race, leaving the ox with second place! Did he cheat – or was he clever, and worthy to be senior-most among the guards?

The fast and competitive tiger and rabbit were the next to arrive. The tiger’s greater size gave him an advantage over the small rabbit, which had to cross the river by hopping on stones and a log. 2023 is the fourth year of the current cycle, named for the fourth-place finisher, the rabbit. When asked their age, Chinese people will commonly answer with the animal of the year they were born in, requiring you to guess which group of the twelve years they were born in.

Speaking of the emperor, in traditional Chinese astronomy, the Jade Emperor’s Palace or “Purple Forbidden Enclosure” was represented by the stars of Ursa Minor (the Little Bear), including the pole star, Polaris. That’s where the spirit of the emperor went after he died. Surrounding that part of the sky were constellations representing the eastern and western walls of the palace (using parts of Draco (the Dragon), kitchen, guest house, archive, advisors, maids-in-waiting, and more.

The Chinese celebrate the New Year with red decorations and firecrackers because, stories say, long ago a mythical beast called Nian was terrorizing rural villages. After many years, an old man declared he would deal with Nian while the rest of the villagers hid during the night. He scared the beast away by hanging red paper around the village and making loud noises. Henceforth, when New Year was approaching, people would wear red clothes, hang up red lanterns, place red scrolls on windows and doors, and use firecrackers to frighten away the Nian. It never bothered the village again.

The Nisga’a indigenous group of British Columbia traditionally celebrate their new year when the crescent moon first appears after its new phase in February or March. Their celebration is called Hobiyee, a name derived from the expression “Hobixis Hee!”, which means “the moon is in the shape of the hoobix”, the bowl of the Nisga’a traditional wooden spoon. The young moon’s orientation after sunset, with its horn-tips pointing upwards, resembles a celestial scoop – ready to be filled with an abundance of salmon, river saak (candlefish), berries, and more. Children gleefully run about with their arms curved upwards, pretending to be the moon. The first month of the Nisga’a year is called Buxw-laks, where buxw means “to blow about” and laḵs means “needles” – a sure sign of winter’s end.

Comets Update

Here’s an update on the two comets that are currently available for viewing from mid-northern latitudes. Both were discovered by the robotic widefield camera of the Zwicky Transient Facility (or ZTF) on Mount Palomar in California, one in 2020 and the other in 2022. The comets’ positions around the north celestial pole mean that only sky-watchers in the Northern Hemisphere can see them. Southern Hemisphere observers can view another comet named C/2017 K2 (Panstarrs) in binoculars. It’s in the southwestern evening sky.

Comet c/2022 E3 (ZTF) is already bright enough to see in full-size binoculars from a dark site and in backyard telescopes. In the past few days, astronomers have been reporting its brightness to be about magnitude 6.0. It will like a faint, greenish, fuzzy patch. The green is produced when diatomic carbon released from the comet’s icy snowball core is ionized by solar radiation.

Comet E3 is predicted to become visible to your unaided eyes from a dark location while it passes nearest to the Earth – at a distance of 43 million km – on the night of February 1. The media have been calling it a “rare green comet”, but comets are commonly greenish. We rarely get a decently bright one. Maybe that’s what they mean?

The orbit of Comet E3 is nearly perpendicular to the plane of our solar system. It is diving down (southward) through the solar system between the orbits of Earth and Mars. Comets normally display their largest coma (fuzzy head) and tail while they are nearest the sun (or perihelion), which happened on January 12. They appear larger and brighter in the sky while they are closer to Earth. You can view and play with Comet E3’s orbit in 3D here.

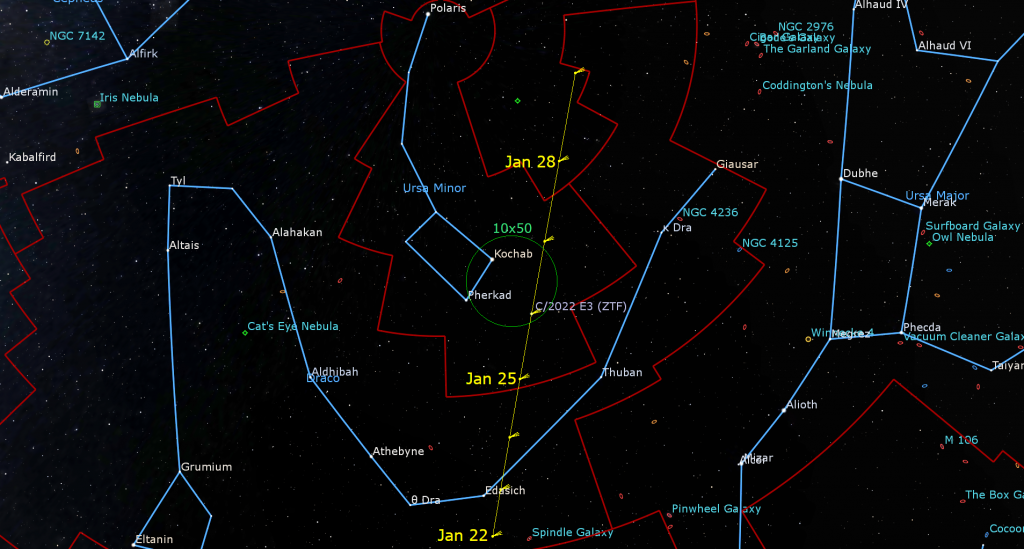

To find Comet E3, take your binoculars outside after it gets dark and face north. The comet is now circumpolar, meaning that it will never set below the horizon for observers at mid-northern latitudes. Since the sky revolves around the North Celestial Pole and nearby Polaris, the comet will travel in a big circle around Polaris during Earth’s 24 hour day. Generally speaking, the comet will sit directly below Polaris (and to the left of the Big Dipper’s handle) at around 7:30 pm in your local time zone. Tonight (Sunday) the comet will barely clear the treetops at 7:30 pm, so wait a couple of hours for it to be carried higher and higher in the northeastern sky. The best time to see something faint like a comet is when it is highest in the sky, so the absolute best views will be the hours before dawn. Don’t worry if that’s too late for you – the situation gets better….

With each passing day the comet will glide several finger widths (or 3.5°) higher in the evening sky, meaning that you can start viewing it earlier and earlier. Its path this week will carry it between the Big Dipper and the Little Dipper. On Sunday night, January 22 it will be high enough for high quality views by about 10 pm local time – sharing your binoculars’ field of view with Draco, the Dragon’s bright star Edasich, which will sparkle above the comet around that time. (By 2 am the star will be rotated to the comet’s left.) On Monday evening, the comet will sit only a finger’s width to the upper right (or 1° to the celestial WNW) of Edasich. On Sunday and Monday, astro-imagers can photograph the comet near several galaxies, including the Spindle Galaxy (Messier 102) and the Splinter Galaxy (NGC 5906).

Comets are known for their tails. Many comets sport two tails – a narrow, blueish one that is composed of glowing ionized particles spread out in a direct line away from the sun, and another broader, dusty tail that is composed of debris dropped as the comet moves through the solar system. That second tail follows the “road” the comet has travelled, so it can be curved. For Comet C/2022 E3 (ZTF), recent images have shown the long, but faint ion tail pointed toward celestial WNW. The dust tail is abright, broad wedge on the northern side of the green coma. In the evening sky, those directions will be towards the right and up, respectively – but a telescope will flip and/or mirror the view. Austrian astronomer Michael Jäger has been posting terrific still and animated images on Twitter as @Komet123Jager.

From Tuesday to Friday the comet will glide closer to the medium-bright star Kochab, the star at the opposite end of the Little Dipper from Polaris. They’ll be binocular-close on Thursday and Friday, but the comet will skip from Kochab’s lower right to the upper right, respectively. Next Sunday night, January 29, the comet will be perched right on the line connecting Polaris to the bright star Dubhe, which marks the outer lip of the Big Dipper’s bowl. Look for the comet a fist’s width from Polaris, or one-third of the span between those stars.

By mid-week Comet C/2022 E3 (ZTF) will be high enough in the sky for viewing at 8 pm (though later will still yield better views).

The other ZTF comet, named C/2020 V2 (ZTF), is in the northern sky, too – but on the opposite side of Polaris near the W-shaped stars of Cassiopeia (the Queen). That location makes it available for viewing as soon as the sky darkens in evening – but you’ll need a telescope and a relatively dark location. The comet is currently only a faint, magnitude 9.5 fuzzy spot in large binoculars, but should show relatively well in 80-mm and larger telescopes, especially now that the moon has left the evening sky. Comet V2 passed closest to Earth in early January. It will remain at about the same brightness over the month as it dives through the plane of the solar system between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. Its perihelion will be later this year. You can play with a nice interactive 3D model of its orbital path here.

This week Comet V2 will be travelling celestial southward past the star Ruchbah (or Delta Cassiopeiae), which marks the peak in the shallower half of W-shaped of Cassiopeia (the Queen). Since the northern sky rolls around the celestial pole during the night, that motion translates to towards the upper left during evening – in the direction away from Polaris.

Unlike Comet E3, this fainter comet is highest in the sky after dusk, and then it descends on the left-hand (western) side of Polaris during evening – so try to view it right after dinner. (Don’t forget to chill down your telescope, with its lens caps on, in a secure location for an hour or two ahead of viewing.) Tonight (Sunday) the comet will form a triangle below and between Ruchbah and Segin, the end star in Cassiopeia. On each subsequent night it will shift almost a finger’s width closer to Ruchbah, passing extremely close to that star on Thursday, January 26! Look for the bright open star cluster named Messier 103 positioned a finger’s width from the Ruchbah-comet duo then. On Saturday and Sunday night, astro-imagers can nab the comet passing close to the faint emission nebula named Sharpless 2-188. The Dragonfly / Owl / ET Cluster (or NGC 457) will sparkle a finger’s width below the comet on the weekend, too.

The Moon

This is the week of the lunar month worldwide when you can enjoy close-up views of our celestial dance partner as it waxes fuller after dinner. The moon reached its new moon phase on Saturday, January 21, triggering the Lunar New Year observed in many Asian countries. You might glimpse the razor thin sliver of the very young crescent moon shining above the southwestern horizon after sunset tonight (Sunday), when it will be positioned a slim fist’s width below (or 8 ° to the celestial southwest of) the bright Venus-Saturn conjunction. Observers near the tropics will see it more easily.

As the waxing moon swings farther from the sun each day, its illuminated phase increases. The zone on the sunshine side of the pole-to-pole boundary between the lit and dark hemispheres is an amazing sight in binoculars and any size of telescope. The sun is just rising over the horizon along that terminator, so its nearly horizontal rays throw long shadows to the west of every bump, ridge, crater rim, and mountain peak. With no atmosphere to scatter light, the shadows are inky black. Keep the telescope ready to go – the view changes hour by hour and night by night.

On Monday, the slender crescent of the young moon will join the Venus-Saturn duo – setting up a wonderful widefield photo opportunity in the west-southwestern sky in early evening. The moon, which will be positioned in Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), a generous palm’s width to the upper left of the two planets, may exhibit Earthshine. Sometimes called the Ashen Glow or the Old Moon in the New Moon’s Arms, the phenomenon is visible within a day or two of new moon, when sunlight reflected off Earth and back toward the moon slightly brightens the unlit portion of the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere.

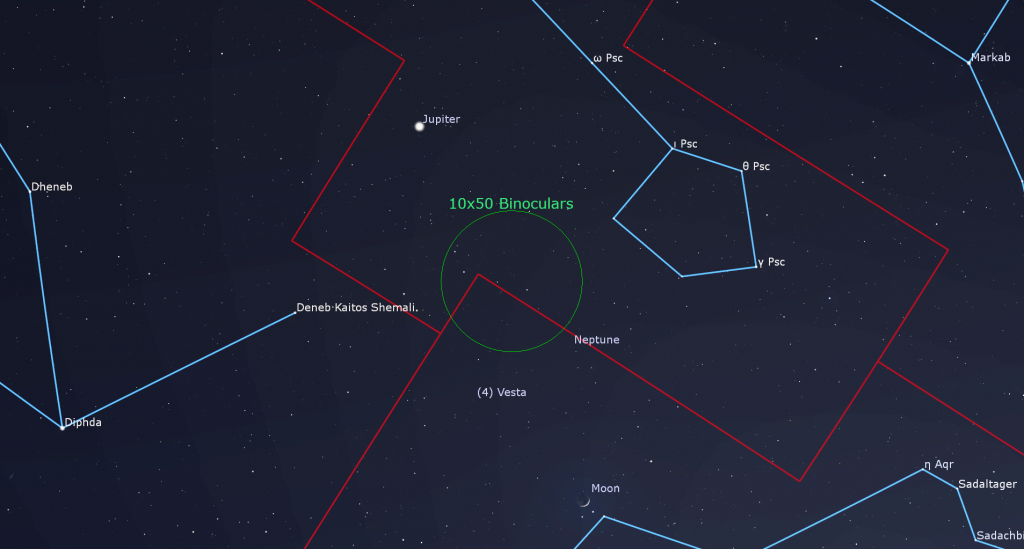

On Tuesday evening, the easterly orbital motion of the waxing crescent moon will carry it towards Neptune and the large asteroid Vesta. In the Americas, the moon will set while it is still about a palm’s width below (or celestial southwest) of them. Observers across the International Date Line in eastern Asia, New Zealand, and Australia can see the moon posing between them on Wednesday evening, when magnitude 7.9 Neptune will be located a generous thumb’s width below the moon and magnitude 8.0 Vesta will shine several finger widths to the moon’s upper left.

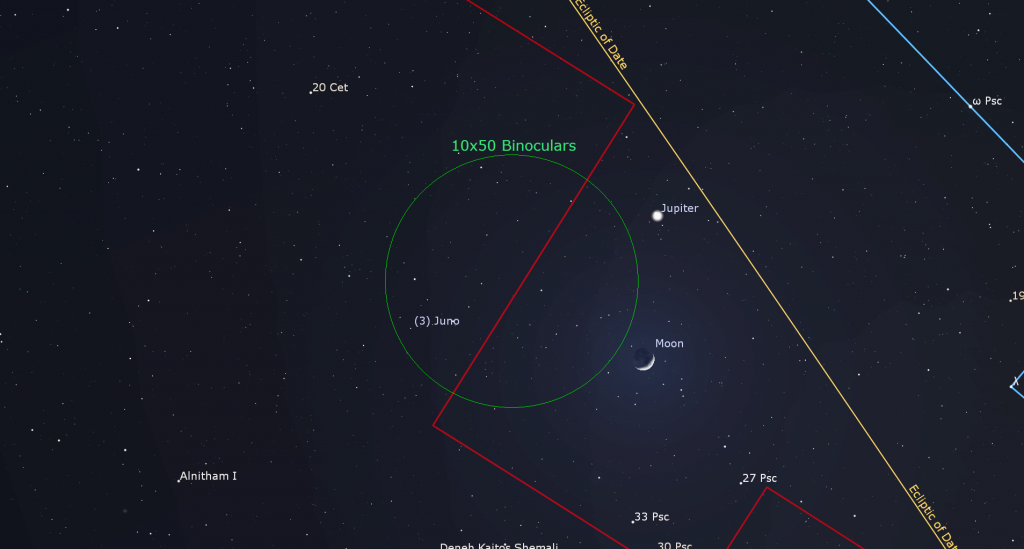

The moon will continue its trip past the planets on Wednesday evening. The 23%-illuminated crescent moon will dance into Pisces (the Fishes), several finger widths below (or celestial south-southwest of) very bright Jupiter. That’s close enough for them to share the field of view in binoculars. Sky-watchers in westerly time zones will see the pair closer together before they drop below the rooftops in mid-evening.

The brightening moon will continue to swim through Pisces until Friday night, and then hop into Aries (the Ram) for a rendezvous with Uranus on Saturday. Before that, though, moon will complete the first quarter of its orbit around Earth at 10:19 am EST (or 15:19 Greenwich Mean Time) on Saturday morning. At first quarter, the 90° angle made by the Earth, sun, and moon will cause us to see it half-illuminated – on its eastern side. At first quarter, the moon always rises around mid-day and sets around midnight, so it is visible in both the afternoon daytime sky and during evening.

On Saturday evening, January 28 in the Americas, the slightly gibbous moon will shine two finger widths to the lower right (or about 2 degrees to the celestial west) of the magnitude 5.7 planet Uranus. The moon’s eastward orbital motion will carry Luna closely past Uranus during the night, eventually allowing them to share the view in a backyard telescope. Observers in Alaska, far northern Canada, Svalbard, and Greenland can see the moon cross in front of (or occult) Uranus starting around 04:30 GMT on January 29. An app like Stellarium will provide the start and end times for the occultation , if it’s visible where you live.

Last week here I described seeing the normally hidden Mare Orientale on the eastern edge of the moon. Due to the moon’s 1.5° axial tilt, its orbital inclination (or tilt) of 5° from the Earth’s orbital plane, and the moon’s orbital ellipticity (or out-of-roundness), the moon nods up-and-down by up to 7° and twists left-to-right up by to 8° while keeping the same hemisphere pointed towards Earth. Over time, this lunar libration effect lets us see an extra 9% of the moon’s total surface without having to leave the ground! Lunar features that are normally smeared along the moon’s edge or completely hidden can rotate into clearer view for a few nights. The librated sector of the moon’s limb migrates clockwise around the moon over a lunar month – but librated features can only be observed if their sector happens to be bathed in sunlight at the same time.

On the coming weekend, the moon will rotate its eastern cheek in our direction, allowing us to see libration’s effect on the moon at a glance by watching Mare Crisium “the Sea of Crises”. That’s the isolated, dark and round feature located near the right-hand (eastern) edge of the moon, just north of the moon’s equator. It becomes fully illuminated starting about four days after new moon each month. Whenever the waxing crescent moon is descending in the western sky after sunset, its eastern edge becomes tilted downwards, towards the lower right – making Mare Crisium a dark blob squarely within the illuminated crescent.

On the weekend, libration will shift Mare Crisium farther than usual from the moon’s edge. Once you’ve spotted it, look nearby for two dark patches positioned closer to the moon’s edge. Those are lunar basins, or maria, named Mare Marginis, which is higher and closer to Mare Crisium, and Mare Smythii, which sits lower and therefore farther away. Those “seas” are difficult to see unless the moon’s eastern limb is rotated towards Earth.

Sunday night’s moon will shine near the bright little Pleiades Cluster, on its way to a Monday night meet-up with Mars.

The Planets

All of the planets will be observable again this week – but we’ll soon have to say goodbye to Saturn.

The speedy innermost planet Mercury will rise over the southeastern horizon at about 6:10 am local time. It will climb a bit higher each morning. If you can see the bright stars Altair in Aquila (the Eagle) and Antares in Scorpius (the Scorpion) before the sky brightens much, hunt for Mercury’s bright, magnitude 0.0 dot below and midway between them. In a backyard telescope, Mercury will display a hazy, half-moon shape. This will be a relatively good appearance for observers in the Northern Hemisphere and a very good one for those in the tropics and farther south.

The best planetary show will happen after sunset, where extremely bright Venus will be shining above the rooftops in the southwestern sky. It, too, is climbing away from the sun, so it’ll appear higher in the sky if viewed at the same time each night. We’ll enjoy Venus as the “Evening Star” until next July! Our cloud-shrouded sister planet will show a featureless, 93%-illuminated disk in your telescope. For the clearest views of it, look as soon as you can find it, when it will be higher and shining through less intervening air. Venus will set around 7 pm local time. Be sure to wait until the sun has completely disappeared before searching for Venus (or Mercury) in binoculars or telescopes.

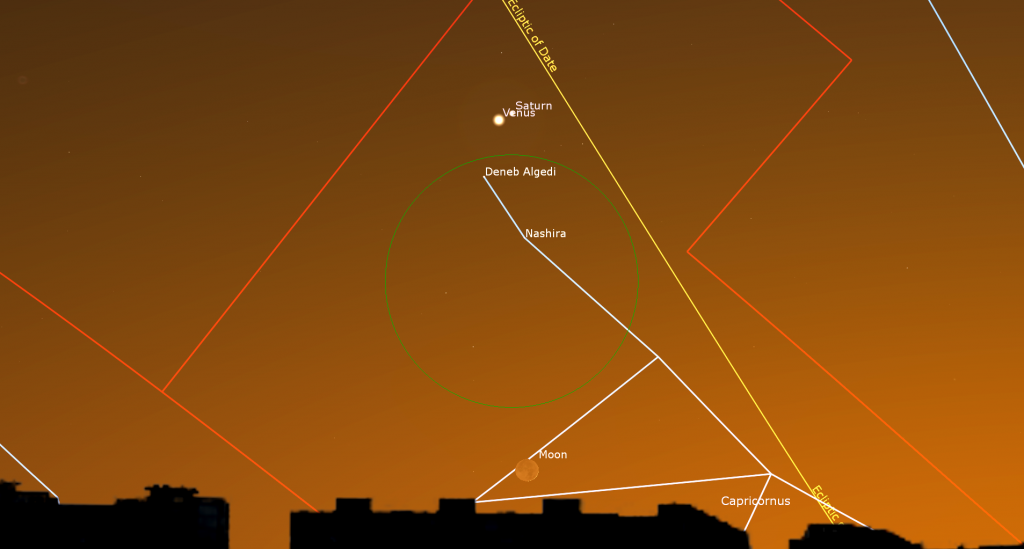

Tonight (Sunday, January 22), Venus will climb past 75 times fainter Saturn in a spectacular close conjunction. The pair will shine above the west-southwestern horizon for an hour after sunset. The two planets will be cozy enough to share the view in binoculars until Tuesday, and they’ll share the view in a backyard telescope’s eyepiece until Monday. At closest approach, Saturn will be positioned just half a finger’s width to Venus’ right (or 20 arc-minutes to the celestial north-northwest) – but your telescope may flip them around. Sharp-eyed observers, especially those at southerly latitudes, might glimpse the very slim crescent of the young moon positioned nearly a fist’s width below the two planets.

For the rest of the week, Venus will climb higher while Saturn and the surrounding stars will be carried lower and sunward by Earth’s orbital motion. The same effect causes the constellations to be replaced each season. Saturn’s descent means our time for clear views of it in a telescope are done for this year. You can still use a telescope to see the planet’s globe encircled by its glorious rings, and possibly its largest moon named Titan! As the sky darkens, the medium-bright tail stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat), brighter Deneb Algedi and half as bright Nashira will shine a thumb’s width below Saturn (or celestial southwest). Saturn will pass the sun in solar conjunction on February 16, and then return to shine in the eastern pre-dawn sky starting around early April. It’ll join the evening sky from July onward.

We’ve still got plenty of time to enjoy Jupiter during evening and Mars all night long. Jupiter’s bright, white, magnitude -2.2 dot will appear halfway up the southwestern sky after sunset. Your binoculars should be able to show Jupiter as a small disk bracketed by its line of four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. The moons’ arrangement varies each night. All four of them will swing to the same side of the planet on Thursday night.

Jupiter will look best in a telescope as soon as you can spot it – while it is still high in the sky. It will sink lower through the evening and set in the west around 10:30 pm local time. Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light bands, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk in early evening on Sunday, Tuesday, and Sunday, and during mid-evening on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday evening. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

The round, black shadows of Jupiter’s Galilean moons are visible through a good backyard telescope when they cross the planet’s disk. On Wednesday evening, Io’s small shadow will cross Jupiter’’s equator from 6:42 to 8:50 pm EST. On Thursday evening, Ganymede’s large shadow will cross Jupiter’s southern hemisphere from 8:05 pm to 10:22 pm EST, but Jupiter will set in the Eastern Time zone before the trip is completed. The events are widely visible over the western hemisphere. Just adjust these quoted times into your own time zone.

The tiny, blue, magnitude 7.9 speck of Neptune will be located almost a fist’s width to the lower right (or 8.5° to the celestial west-southwest) of Jupiter this week. That’s a bit less than than halfway to the medium-bright star Hydor (or Lambda Aquarii), which is easy to see in binoculars. Like Jupiter, try to view Neptune while it is higher right after dusk. The large, relatively faint, magnitude 9.6 asteroid named (3) Juno will be positioned a palm’s width to the lower left of Jupiter all week. The crescent moon will shine near them on Wednesday only.

Since our closest approach back on November 30, Earth has increased our distance from Mars dramatically. For that reason, the red planet has become dimmer in the sky and smaller in telescopes – but you can still see the major dark markings on its ochre 11.8 arc-seconds-wide disk through a small, but good quality telescope using a high magnification eyepiece. If you have coloured filters for your telescope, see if the blue, orange, or red one improves the view.

During early evening Mars will be positioned high in the southeastern sky above the stars of Orion (the Hunter) – just above the very bright, reddish star Aldebaran, which marks the angry eye of Taurus (the Bull). The Pleiades star cluster will be twinkling less than a fist’s width to Mars’ upper right (celestial west). Over the next weeks, you’ll notice that Mars is shifting eastward above Aldebaran, and moving a bit farther away from the Pleiades each night. For now, Mars will climb very high in the south around 8:30 pm local time (its absolute best telescope viewing time), and then descend westward, allowing early risers to spot it above the western horizon for several hours before dawn.

The blue-green dot of Uranus is located about one-third of the way from Mars towards Jupiter. That’s 1.3 fist widths to the lower left (or 13° to the celestial southeast) of Hamal and Sheratan, the brightest stars in Aries (the Ram). Closer guideposts to Uranus are several medium-bright stars, including Al Butain II (or Rho Arietis), and Omicron and Sigma Arietis, which will appear several finger widths from the planet – in the same binoculars field of view. Those faint stars mark the hooves of the Ram. Magnitude 5.7 Uranus will already be high enough for telescope-viewing, in the upper part of the southern sky, after dusk this week. It will climb to its highest point in the southern sky around 7 pm local time and then set around 2 am. On Monday, Uranus’ motion through the background stars of southern Aries will slow to a stop – completing a westward retrograde loop that it began in late August. After that, the planet will begin to slip eastward again.

The main belt asteroid designated (2) Pallas is currently shining with a visual magnitude of 7.7, which is within reach of binoculars and backyard telescope. This week Pallas will still be situated in southwestern Canis Major (the Big Dog), several finger widths to the upper right (or 4.3 degrees to the celestial west) of the bright, rear paw star Adhara. During January and February the asteroid will slide upwards (northwest) through the legs of the dog and closer to Sirius. Wait until the asteroid has risen higher, at around 10:30 pm, for the best views of it.

Treats in Taurus

If you missed last week’s tour of Taurus (the Bull), I posted it with pictures of Taurus’ best objects here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras (weather permitting), answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. On Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Thursday evening, January 26 at 8 pm EDT, Roy Thomson Hall in Toronto will present physicist and bestselling author Professor Brian Greene in BEYOND THE STARS – A Journey to the Edge of Space, Time, and Meaning: An Evening with Professor Brian Greene. Details and tickets are available here.

RASC’s has resumed Public sessions at the David Dunlap Observatory – but they are still offering several online programs from home. The modest fee supports RASC’s education and public outreach efforts at DDO. Only one registration per household is required. Prior to the start of the program, registrants will be emailed the virtual program link.

On Saturday night, January 28 from 7 to 8:30 pm EST, tune in for DDO Up in the Sky. During the family-friendly session, RASC astronomers will live-stream views through their telescopes and the giant 74” telescope at DDO (pre-recorded views will be used if skies are cloudy). Only one registration per household is required. Deadline to register for this program is Wed., Jan 25, 2023 at 4 pm. Prior to the start of the program, registrants will be emailed the virtual program links. More information is here and the registration link is here.

On Sunday afternoon, January 29 from 12:30 to 1 pm EDT, tune in for DDO Sunday Sungazing. Safely observe the sun with RASC, from the comfort of your home! During these family-friendly sessions, a DDO Astronomer will answer your questions about our closest star: the sun! Learn how the sun works and how it affects our home planet. Live-streamed views of the sun through small telescopes will be included, weather permitting. Only one registration per household is required. Deadline to register for this program is Wednesday, Jan 25, 2023 at 3 pm. Prior to the start of the program, registrants will be emailed the virtual program links. More information is here and the registration link is here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcast with Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, January 31 at 3:30 pm EST. We’ll focus on sights to see along the winter Milky Way and some cold weather stargazing tips. Then we’ll highlight the next batch of RASC’s Finest NGC objects. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!