Vesta Passes the Helix Nebula, the Post-midnight Moon Meets Planets, Saturn Shines Brightest, Spotty Jupiter, and Moonlight Sights!

This spectacular Perseids meteor was captured by RASC member Don Hladiuk of Calgary at 3:53 am MDT on August 13, 2022. Follow Don on Twitter at @Astrogeo (Yes – we’re each other’s doppelganger!)

Hello, mid-August Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of August 14th, 2022 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will leave evening skies darker worldwide this week as it wanes through third quarter, so I highlight some moonlight-friendly things to see. The moon will pass by to a succession of bright and faint planets. Saturn will peak at opposition tonight (Sunday), Vesta will pass telescope-close to the Helix Nebula, and Jupiter will sport both the Great Red Spot and moon shadow transits. Read on for your Skylights!

Perseids Meteor Shower

The spectacular annual Perseids Meteor Shower will taper off over the next few weeks, so keep an eye out for them this week – especially during evening before the moon has risen. I posted details about watching meteors last week here.

The Moon

This is the week of the lunar month when our natural nightlight will be decreasing its angle from the sun, causing the moon to rise late and then linger into morning like the ghost of supermoons past. While the moon glides east along its orbit, it will also wane in illuminated phase. Everyone on Earth sees the same phase of the moon as our revolving planet lifts the moon into view, time zone by time zone. The only twist is that the moon appears inverted when from the opposite hemisphere, causing its phases to be flipped left-for-right.

Tonight (Sunday) the moon will accompany Jupiter across the sky. After the duo rises above the eastern horizon around 10:30 pm local time, the waning gibbous moon will shine a palm’s width to the right (or 5 degrees to the celestial southwest) of the extremely bright planet Jupiter – just close enough for them to be viewed together in your binoculars. See if you can also detect Jupiter’s own little moons in a line flanking the planet. Through the night, the diurnal rotation of the sky will carry the moon below Jupiter. On Monday night, the moon’s easterly orbital motion will cause it to hop to Jupiter’s lower left. On both nights, the moon will be swimming its way along the crooked border between Cetus (the Whale) and Pisces (the Fishes).

Starting after 11 pm local time on Wednesday night, August 17 in the Americas, the bright moon will shine a slim palm’s width to the upper right (or 4.5 degrees to the celestial west-southwest) of the blue-green, magnitude 5.7 speck of Uranus in Aries (the Ram) – close enough for them to share the view in binoculars. After midnight, reddish Mars and the Pleiades star cluster (aka the Seven Sisters and Messier 45) will appear to their lower left. The duo will climb high into the southern sky towards dawn. By then the easterly orbital motion of the moon will shift it much closer to Uranus. Hours later, observers from Micronesia to most of Hawaii and the Bering Sea can see the moon cross in front of (or occult) Uranus at around 16:00 GMT on August 18 – the eighth in a series of consecutive lunar occultations of that planet.

On Thursday night, it will be Mars’ turn for a monthly visit by the moon. Once the waning, half-illuminated moon clears the eastern treetops a little before midnight local time, the bright, reddish dot of Mars will be shining a few finger widths to its lower left (or 3 degrees to the celestial east) – with the bright Pleiades then to the moon’s upper left. The trio will remain binoculars-close all night long. By dawn, the moon will have shifted between Mars and the cluster.

The moon will officially complete three quarters of its orbit around Earth, measured from the previous new moon, on Friday, August 19 at 12:36 am EDT or 04:36 Greenwich Mean Time, which converts to Thursday, August 18 at 9:36 pm PDT. At the third (or last) quarter phase the moon appears exactly half-illuminated, on its western, sunward side. The week of dark, moonless evening skies that follow this phase are the best ones for observing deep sky targets.

The moon’s trip through the stars of Taurus (the Bull) will continue from Friday until Sunday morning. Early risers on Sunday can see the pretty sight of the old crescent moon poised between the winter constellations of Orion (the Hunter), Taurus, Gemini (the Twins) and Auriga (the Charioteer). Their bright stars form a big asterism called the Winter Hexagon. The moon will be in its centre.

The Planets

By the end of this week, folks living at mid-northern latitudes will have six planets to view in evening – sort of. The bright trio of Saturn, Jupiter, and Mars will appear to our unaided eyes from midnight to dawn. Faint Uranus and Neptune will be there, too, if you know which dots they are – and elusive Mercury will be skipping over the western horizon after sunset. Let’s break it all down.

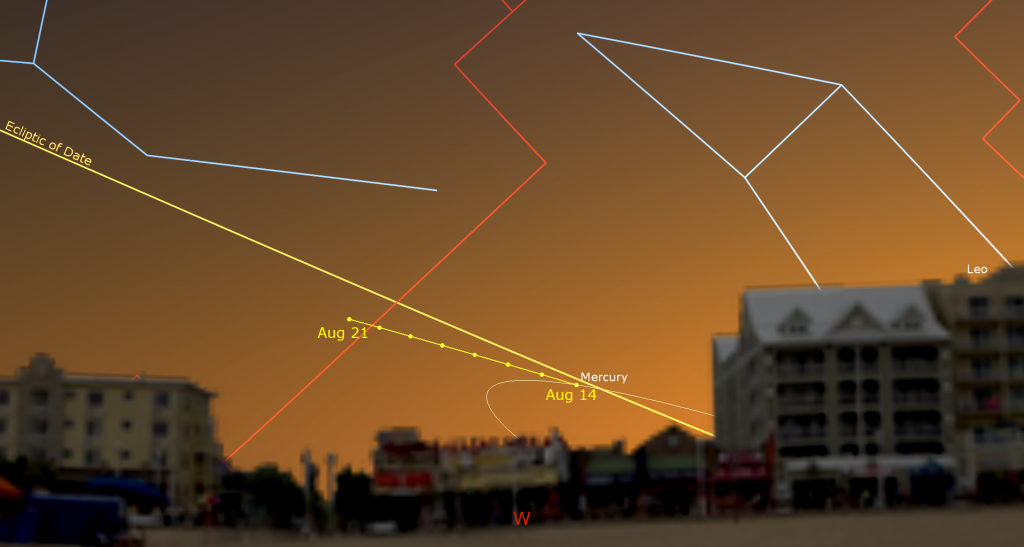

Mercury won’t reach its widest angle from the sun (usually the best time to see it) until late this month. This week, Mercury’s position below a very tipped ecliptic will be holding the speedy planet too close to the horizon for easy viewing from mid-northern latitudes. Once the sky begins to darken about 30 minutes after sunset, Mercury will become visible as a magnitude 0.0 point of light, positioned due west a bit more than 1.5 fist diameters to the left of where the sun set, and only a few finger widths above the horizon line. The optimal viewing time will be 8:45 to 9 pm local time, but you’ll need a cloud-free, unobstructed vista. Observers at Caribbean latitudes and south of there will see Mercury easily all month long – its best appearance of the year.

The end of civil twilight will occur before 9 pm local time this week. Around then, you might be able to glimpse the dot of Saturn shining above over the east-southeastern horizon. Never fear, the yellowish planet will climb above the trees by 10 pm. Then it will cross the lower part of the sky during the night – culminating due south around 1:30 am local time and then setting in the west-southwest before sunrise. (Culminating is the word for an object’s highest point in the sky.) This year Saturn is shining among the faintish stars of eastern Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). The two small stars shining just below Saturn are Deneb Algedi on the left (east) and Nashira on the right (west). They represent the tail of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). Since Saturn is now moving slowly westward in a retrograde loop that will last until late October, you can watch it shift more to the right (or celestial west) above those stars over the next few weeks. Retrograde loops occur when Earth, on a faster orbit closer to the sun, passes the distant planets and asteroids “on the inside track”, making them appear to move backwards across the stars.

Tonight (Sunday, August 14), Saturn will reach opposition for 2022. Objects at opposition are visible all night long – rising at sunset and setting at sunrise – because Earth is positioned between them and the sun. At opposition, Saturn will be at a distance of 1.325 billion km or 73.7 light-minutes from Earth, and it will shine at magnitude of 0.28 – its brightest for the year. While planets at opposition always look their brightest, Saturn will be intensified by the Seeliger effect, backscattered sunlight from its rings. Even a small telescope will show Saturn’s apparent disk diameter of 18.8 arc-seconds, and its 43.7 arc-seconds-wide rings. Saturn’s rings will become more edge-on to us every year until the spring of 2025. This year they have closed enough for Saturn’s southern polar region to extend well beyond them. See if you can see the Cassini Division. It’s a narrow, dark gap that separates Saturn’s main inner ring from its outer one.

A small telescope will also show several of Saturn’s moons – especially its largest, brightest moon, Titan! From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves all around the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn. During evening this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the upper right (celestial west) of Saturn tonight (Sunday) to the left (celestial northeast) of the planet next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope might flip that view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope?

The main belt asteroid designated (4) Vesta, which is actually brighter than Uranus nowadays, is currently traveling westward a generous fist diameter to Saturn’s lower left (or 11.5° to its celestial east-southeast). Telescope owners and astro-imagers should note that Vesta will be also travelling just a thumb’s width above (or 1.5° to the celestial north) of the spectacular, but faint Helix Nebula, also known as NGC 7293, until mid-week. For best results observe them during the wee hours, when they have climbed highest in the sky. Several similarly-bright stars will be arrayed around Vesta and the nebula, allowing you to locate the area using binoculars.

This week, extremely bright Jupiter will appear above the eastern horizon shortly after 10 pm local time, and then spend the night following fainter Saturn across the sky. The planet will climb high enough to look good in any telescope from about 11 pm local time onward. Early risers can spot the planet halfway up the southwestern sky just before sunrise. Good binoculars will show Jupiter’s disk flanked by its row of four Galilean moons, which dance about the planet. If you see fewer than four, then one or more is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, lurking in Jupiter’s dark shadow, or two moons are occulting one another. Any size of telescope will show Jupiter’s dark bands running parallel its equator.

For observers in the Americas, the Great Red Spot will cross Jupiter’s disk late on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday night, and also during the wee hours of Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday morning. The small, black shadows of Jupiter’s Galilean moons are visible through a backyard telescope when they cross the planet’s disk. On Monday night, August 15, two shadows will cross at the same time, accompanied by the Great Red Spot! Io’s small shadow will began to cross at 11:25 pm EDT on Monday evening. A few minutes after midnight EDT the larger shadow of Ganymede and the red spot will rotate into view. Io’s shadow will complete its passage at 1:39 am EDT, while Ganymede’s shadow and the spot will depart at 3 am and 4 am EDT, respectively. Observers in the Pacific Time Zone will only be able to observe the later stages of the event, which will already be underway when Jupiter rises in late evening. The small round, black shadow of Europa will cross Jupiter’s disk with the Great Red Spot on Saturday morning from 3:21 am to 5:53 am EDT.

Magnitude 7.8 Neptune is theoretically observable in binoculars, but a telescope makes it far easier. This summer, the distant planet’s faint blue speck will be positioned 1.3 fist diameters to Jupiter’s upper right, and a thumb’s width to the upper right (or 1.6° to the celestial west) of a small star named 20 Piscium, which sits on the line joining Jupiter to Saturn. Neptune has a large moon named Triton that is visible in large aperture telescopes, especially during the next couple of months when we’re closer to the planet.

Medium-bright, reddish Mars will rise above the east-northeastern horizon by midnight local time and will clear the eastern rooftops, along with the Pleiades star cluster to its upper left, about an hour later. Mars will be brightening and growing larger as Earth’s faster orbit gradually draws us closer to it over the coming months. In a telescope, Mars will show a tiny, 85%-illuminated disk. Magnitude 5.76 Uranus will be shining about a fist’s width to the upper right (or 8° to 12° to the celestial west) of Mars – but Mars is speeding away eastward. Without Mars to help you, the brightest guidepost to Uranus is the medium-bright star named Botein (or Delta Arietis), which will appear several finger widths to Uranus’ left (or 3° to the celestial northeast). Uranus will be easiest to see when it’s higher in the sky, in the hour before dawn. Don’t forget that the waning moon will photo bomb the scene after midnight on Thursday night.

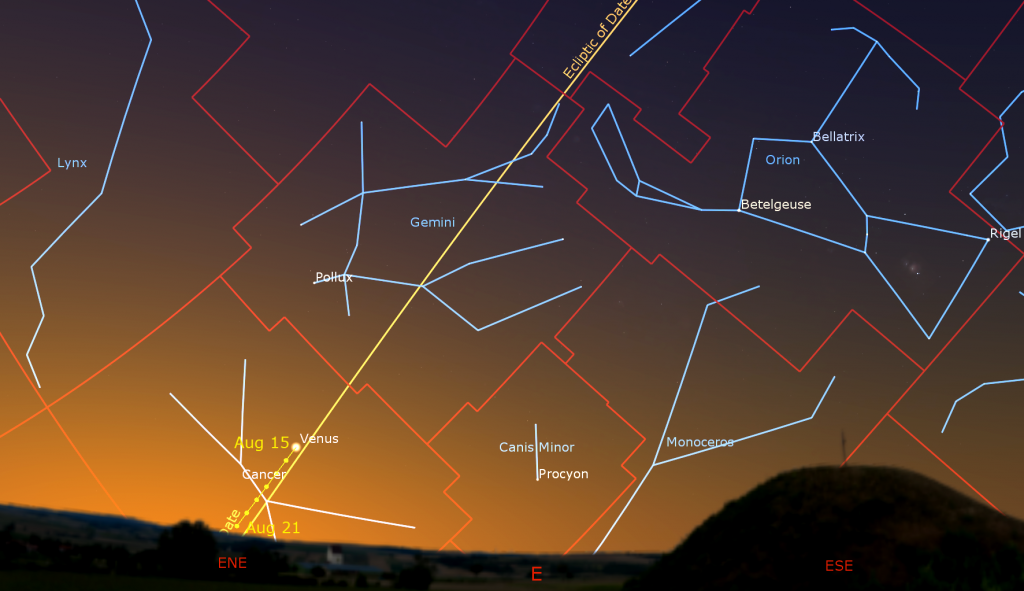

Extremely bright Venus will rise in the east at about 4:45 am local time this week – but it won’t climb very high before sunrise – unless you live in the tropics. The planet is slowly shifting closer to the sun, so we’ll lose sight of it in the coming weeks. For now, Venus will exhibit a waxing, nearly-round shape when viewed in a telescope or in good binoculars. Early risers can look for the two bright stars Castor and Pollux shining above the planet, and the tilted form of Orion (the Hunter) off to their right. On Wednesday and Thursday, Venus will skim the lower right (celestial south) edge of the big Beehive star cluster or Messier 44 in Cancer (the Crab) – but you’ll need to be viewing from a southerly latitude to see them.

Moonlight Sights

The late-rising moon this week will let us view one of the best asterisms in the sky, the Teapot-shaped stars of Sagittarius (the Archer). This informal star pattern features a flat bottom formed by the stars Ascella on the left (east) and Kaus Australis on the right (west), a pointed spout on the right (west) marked by the star Alnasl, and a pointed lid marked by the star Kaus Borealis. The stars Nunki and Tau Sagittarii form a handle on the left-hand (eastern) side. The bent line of three stars named Kaus – Borealis (north), Meridianalis (center), and Australis (south) – refer to the archer’s bow. The center of our galaxy sits only a palm’s width to the right of Alnasl. When the asterism reaches its maximum height above the southern horizon, around 9:30 pm local time, it will be tilted west, as if it’s serving its hot beverage, and the Milky Way represents the rising steam.

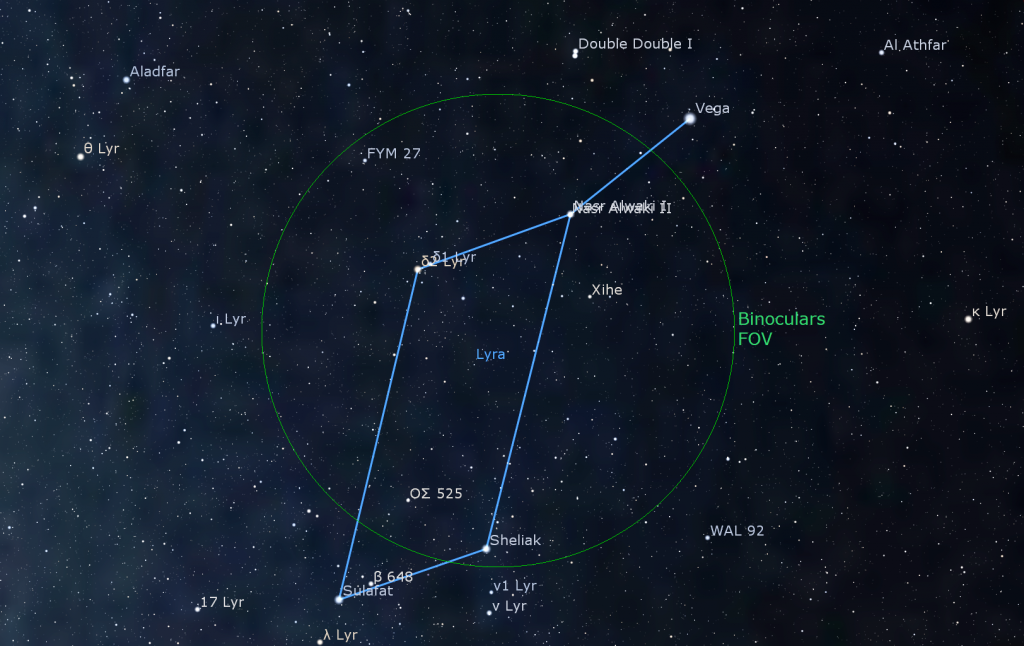

Nearly overhead, way above Sagittarius, resides Vega, brightest star in Lyra (the Harp). At magnitude 0.03, Vega is the brightest star in the summer sky, mainly due to its relative proximity – it’s only 25 light-years away from the sun. Vega forms a little triangle with two other dim stars, each about a finger’s width apart. If you stand facing south, the star to Vega’s upper left is named Epsilon Lyrae, also known as the Double Double. Can you tell it’s actually two stars crammed tightly together? Try using binoculars. When magnified in a telescope, each of those stars splits again!

Each corner of Lyra’s parallelogram is marked by a double star. Zeta Lyrae (ζ Lyr), the corner closest to bright Vega and the third corner of the little triangle with Vega and Epsilon, can be split with binoculars. Both components are white – one star slightly brighter than the other. Each of these stars also has a partner that is too close together to split visually. Moving clockwise, the southwest corner star is Sheliak, the brightest of a tight little grouping of stars visible in a telescope. Sheliak itself has a close-in, dim companion in an eclipsing binary system with a 13-day period. The hot, blue giant star Sulafat sits at the farthest corner from Vega. 620 light-years-distant Sulafat is much larger than Vega – an old star on its way to becoming an orange giant many years from now. Add the slightly dimmer stars Lambda Lyrae and HD 176051 to its south and west, respectively to form a triple star visible with unaided eyes. Delta Lyrae (δ Lyr) marks the northeast corner of the parallelogram. Sharp eyes and binoculars will easily split the double into one blue and one red star. The blue star is one hundred light-years farther away than the red one; they just happen to appear close together along the same line of sight.

The distinctive constellation of Corona Borealis (the Northern Crown) sits halfway up the western evening sky, about two fist diameters above (or 20 degrees to the northeast) of the bright star Arcturus. A circle of seven stars approximately 7 degrees in diameter forms a tiara festooned by the bright star Alphekka or “jewel”. In mythology, this crown was given to Princess Ariadne of Crete by Dionysus, who married her years after she helped Theseus escape the Minotaur. Most of Corona Borealis’ unaided-eye stars are variable. Alphekka is a hot, blue-white, A1-class star 78 light-years from the sun and is similar in nature to Vega and winter’s Sirius, which are much closer. It is also an eclipsing binary star, in which a smaller orbiting companion star passes in front of the main star every 17.3 days, causing the combined light output to dim slightly.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, August 16 at 3:30 pm EDT, when we’ll do a summer planet preview! Plus, we’ll continue with our Messier Objects observing certificate program. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Space Station Flyovers

The ISS (or International Space Station) will not be visible gliding silently over the GTA this week.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!