Watch the Moon Wax, Mercury at Max, Medusa Blink, and Bright Stars Blaze!

An ISS transit on Thursday night, January 21 will pass across the moon’s disk for 0.6 seconds at 6:08:39.8 pm EST. The pass will be observable by observers across Port Perry, northern Toronto / southern Richmond Hill, Brampton, and Cambridge, Ontario. Find details at https://transit-finder.com/ and www.astrogeo.ca/skylights/. This image by Eric Holland was taken from Palo Alto, California, USA with an exposure time of only 1/667 of a second. NASA APOD for April 2, 2019

Hello, Moongazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of January 17th, 2021 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together!

The moon will shine in the evening sky all over the world this week, offering spectacular sights in binoculars and telescopes. I tour the bright stars that don’t mind moonlight. Red Mars will pass telescope-close to blue-green Uranus on Wednesday evening. Mercury will gleam in the southwest after sunset, and you can watch the variable star Algol, Medusa’s eye, change in brightness. Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon

This is the best week of the lunar month for viewing the moon worldwide. Our natural neighbour will already be shining in the evening sky by sunset, allowing even the youngest stargazers to see its sights before bedtime!

Today (Sunday) the moon will rise before noon and set at 10 pm local time, all the while showing a pretty crescent phase among the modest stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). Neptune will be sitting less than a fist’s diameter to the moon’s lower right – but bright moonlight does that dim planet no favours.

From Monday through Wednesday, the moon will wax fuller while it travels east along the border between Cetus (the Whale) and Pisces (the Fishes). On Wednesday at 4:01 pm EST (or 21:01 Greenwich Mean Time), the moon will complete the first quarter of its orbit around Earth. At that time, the relative positions of the Earth, sun, and moon will cause us to see the moon half-illuminated – on its eastern side. At first quarter, the moon always rises around noon and sets around midnight.

The boundary line that separates the lit and dark hemispheres of the moon, from its north pole to its south pole, is called the terminator. At first quarter the terminator becomes a straight line – as viewed from Earth. On the nights leading up to first quarter, and those following it, the terminator becomes curved. That’s one of the ways ancient astronomers inferred that the moon was a sphere orbiting Earth. (Try shining a flashlight onto a tennis ball in a dark room and observe how the “phase” of the ball changes as you vary the angle between the arm holding the light and the arm holding the ball.)

The terminator steadily migrates from east to west (or right to left when viewed from the Northern Hemisphere on Earth). To your unaided eyes that motion is noticeable from night to night. In binoculars and telescopes you can even watch it move in minutes and hours! The sunlight reaching the moon just to the right of that line (or lunar east) is nearly horizontal – so it casts long shadows to the left (west) of the terminator. With no atmosphere on the moon to scatter light, the shadows are a deep black. Even the subtlest topographic bumps and valleys are enhanced when illuminated that way. And the tallest peaks and crater rims reveal themselves when they catch the sunlight before the terminator has moved over them. By noting how far ahead the peaks were lit, the lengths of shadows, and how long it took for dark craters to fill with light, early astronomers could “measure” the moon’s topography!

On Wednesday night the moon will also sit a generous palm’s width to the lower right (or 7 degrees to the celestial southwest of) the bright, reddish dot of Mars – with dimmer Uranus close to Mars. By the time the group sets in the west after midnight, the diurnal motion of the sky will shift the moon to Mars’ lower left. You can also try to spot Mars in binoculars during the late afternoon by using the moon below it as your guide. On Thursday, the moon will be carried to the left of Mars.

On Thursday and Friday, the terminator will fall just to the left (or lunar west) of Rupes Recta, also known as the Straight Wall. This feature is very obvious in good binoculars and backyard telescopes. The rupes, Latin for “cliff”, is a north-south aligned fault scarp that extends for 110 km across the southeastern part of Mare Nubium – that’s the large dark region in the lower third of the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere (under Wilma Flintstone’s chin, if you are used to seeing her sideways profile on the moon, as I am). The Straight Wall is always prominent a day or two after first quarter, and again just before third quarter. For reference, the Straight Wall is located due north of the very bright crater Tycho.

On Friday night, the waxing gibbous moon (i.e., more than half illuminated and growing) will enter Taurus (the Bull). The moon will be positioned about a palm’s width below the bright little Pleiades star cluster and 1.4 fist diameters to the right of Taurus’ brightest star Aldebaran. (I discussed the cluster last week, and you can even listen to voice-over artist Susan Trishel Monson narrate my story on Soundcloud https://soundcloud.com/susantrishel/the-pleiades!) By the time the moon sets at 3 am local time, the rotation of the sky will move it below and between the bright star and cluster.

On Saturday night, the bright moon will move to sit just above (or to the celestial north of) the triangular set of stars that form the bull’s face. The whole star pattern will fill your binoculars’ field of view. To better see them, just hide the moon above the view. On Saturday and Sunday night, look for the Golden Handle on the moon, too. On those nights, the terminator will fall to the left (or lunar west) of Sinus Iridum, the Bay of Rainbows. The circular, 249 km diameter feature is a large impact crater that was flooded by the same dark basalt rock that filled the much larger Mare Imbrium to its right (lunar east). Sinus Iridum looks like a rounded, handle-shape on the western edge of that mare. You can see it with sharp eyes – and easily in binoculars and backyard telescopes. The “Golden Handle” is produced because slanted sunlight is brightening the eastern (right-hand) side of the prominent, curved Montes Jura mountain range (the old crater rim) that surrounds the bay on the top and left (north and west). The rim extends into Mare Imbrium as a pair of protruding promontories named Heraclides and Laplace at the bottom and top, respectively. Sinus Iridum is almost craterless, but hosts a set of northeast-oriented dorsae or “wrinkle ridges” that are revealed in telescope views at this phase. I posted a close-up photo of the area here.

The Planets

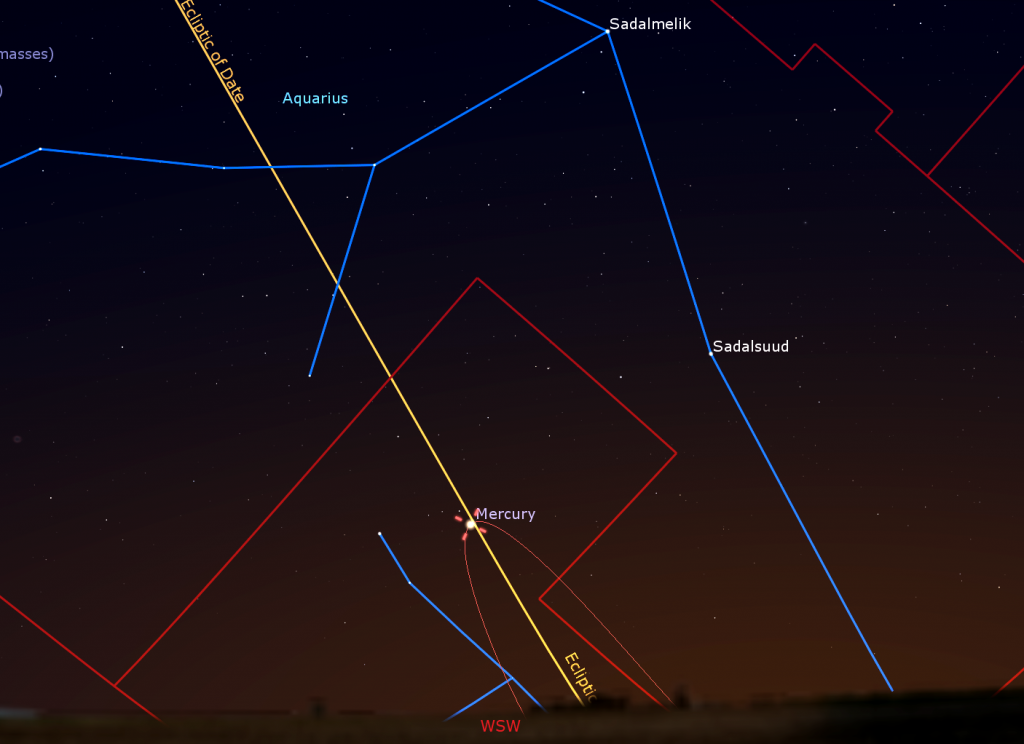

Mercury will be fairly easy to see after sunset this week – but you’ll need an unobstructed view of the southwestern horizon, and no clouds. Tonight (Sunday) you can start looking for the speedy planet at about 5:30 pm in your local time zone, when it will sit less than a fist’s diameter above the horizon. The best viewing time, with the sky darkening and the planet lower, but brightening, will be between 5:45 and 6 pm.

Mercury will climb higher every night until Saturday. On that day Mercury will reach greatest eastern elongation – its widest separation, 19 degrees from the Sun. That greater angle from the sun will allow Mercury to shine in a dark sky before it sets just before 7 pm local time. With Mercury positioned close to the evening ecliptic, this appearance of the planet will be fantastic for Northern Hemisphere observers, but it will not be ideal for observers in the Southern Hemisphere. Viewed in a telescope the planet will exhibit a waning, half-illuminated phase. Be sure that the sun has completely disappeared below the horizon before you search for Mercury with binoculars and telescopes.

When the sky darkens at about 6:30 pm local time, bright, reddish Mars will appear shining high in the southern sky. Then it will spend the rest of the evening descending into the west before setting at 1:30 am local time. Look for the stars of Aries (the Ram), Hamal (brighter, at magnitude 2.0) and Sheratan (magnitude 2.6), sitting a fist’s diameter above Mars (or 9 degrees to the celestial north).

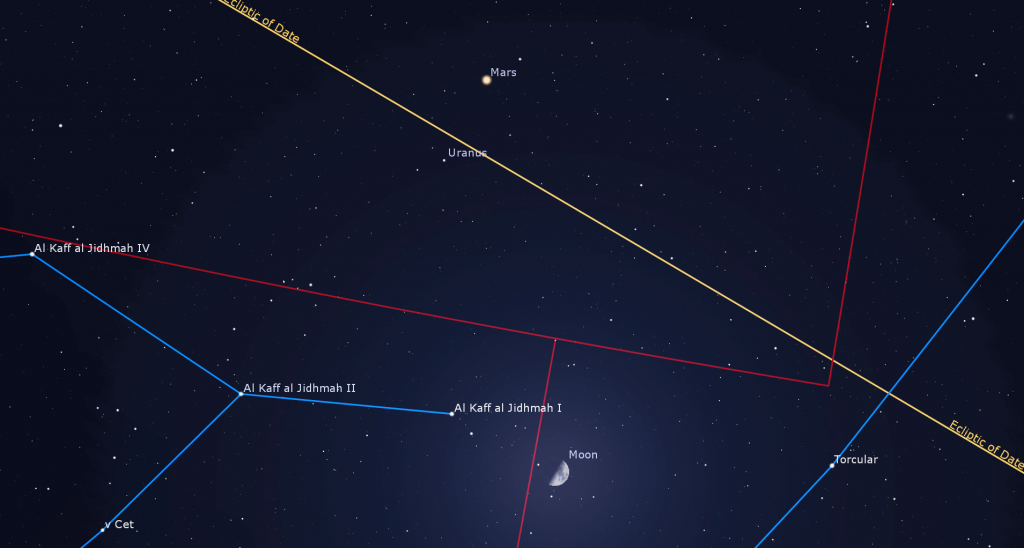

Mars is steadily moving eastward along the ecliptic. On Wednesday night, the red planet will pass only a thumb’s width above (or 1.6 degrees to the celestial north of) dim, blue-green Uranus, which is also sitting among the stars of southern Aries. The close pass will allow both planets to appear together in the eyepiece of your telescope at low magnification – but Mars will outshine magnitude 5.7 Uranus by a factor of 164! Uranus will resemble the stars near it – but the planet won’t twinkle as much, and it will shine with a blue-green tint. On that same evening, the waxing, half-illuminated moon will be positioned below the two planets.

This week, bright Venus might be glimpsed sitting low over the southeastern horizon at about 7:20 am, before the sun rises. Our sister planet has been sliding towards the sun for some time now, and only its intense magnitude -3.9 brightness has kept it visible within the dawn glow. After mid-April Venus will return to visibility low in the west-northwestern sky after sunset.

The Bright Stars of January

The cold clear nights of winter have arrived. Here’s your guide to the many bright stars you can pick out with your unaided eyes in the evening sky over the next month or so – even when the moon is around. I’ve put their brightness rankings (3rd brightest in the night sky, 7th, etc.) in brackets.

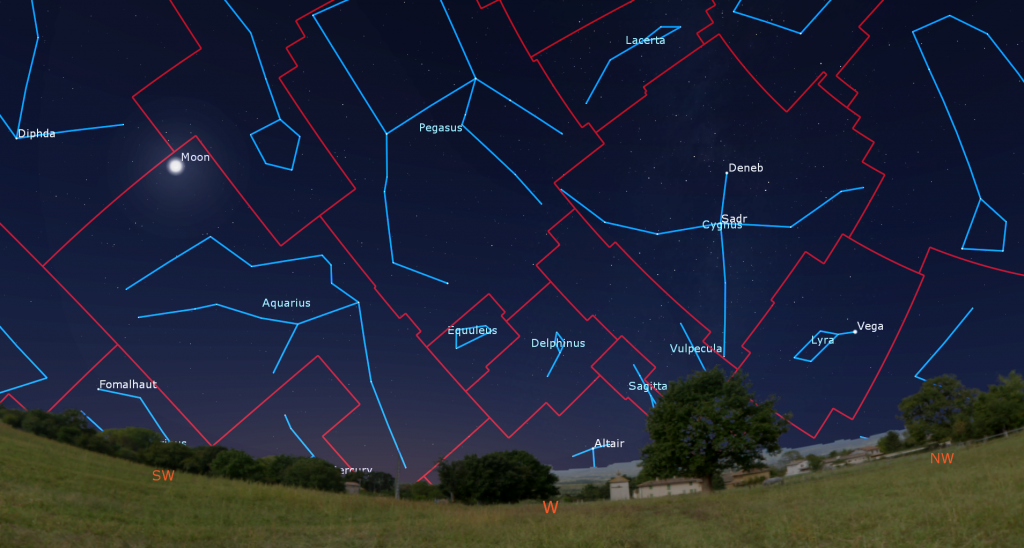

Let’s start in the western half of the sky because those stars set first. If you have an unobstructed southwestern horizon, look as soon as it’s dark for bright Fomalhaut (18th) sitting very low above the southwestern horizon. Looking directly west, the three bright corners of the Summer Triangle still shine brightly in the early evening. The lowest of the three is Altair (12th) in Aquila (the Eagle). A bit higher, and about 3.4 outstretched fist diameters to the right of Altair, is Vega (5th) in Lyra (the Lyre). Deneb (19th) sits above and between those two. All three are hot, bluish white stars. Deneb is the tail of Cygnus (the Swan), and you should be able to see the great bird flying head-down into the west – along the Milky Way. Altair and Vega set about 7 and 8:30 pm local time, respectively. Deneb sets much later – at about 12:40 am local time.

Next, turn fully around and look about halfway up the eastern sky. Bright yellowish Capella (6th) is on the left, with orange-ish Aldebaran (14th) located about three fist widths to the right of it. Capella is the brightest star in the large circular constellation of Auriga (“Oar-EYE-gah”) (the Charioteer), while Aldebaran is the baleful red eye of Taurus (the Bull), whose triangular face is tilted sideways to the left. Both of these constellations will be higher in late evening.

The well-known constellation of Orion (the Hunter) sits directly below Aldebaran. His eastern shoulder is the old and bright reddish star Betelgeuse (11th), and his opposite foot is a bluish star of similar brightness named Rigel (7th). These two stars are hundreds of light-years away. Orion’s three-starred belt is a highlight of the winter sky. From east to west (lower left to upper right) they are Alnitak (30th), Alnilam (29th), and Mintaka (67th). The three stars are evenly spaced – almost exactly 1.3° (about three moon diameters) apart. Orion’s other shoulder is marked by bluish white Bellatrix (26th), and his opposite foot is called Saiph (53rd).

To the left of Orion sits the zodiac constellation of Gemini (the Twins). Its brightest stars are yellowish Pollux (17th) and pale white Castor (23rd). Like many twins, they are a challenge to keep straight which is which. Castor, the higher star, rises first, just as “C” precedes “P” in the alphabet.

The night sky’s brightest star rises in the sky below Orion after 6:15 pm local time. Sirius (1st), also called the Dog Star because it resides in the constellation of Canis Major (the Large Dog), is a very hot, bluish-white star. It’s so bright because it is our neighbour – positioned “just up the street” at only 8.6 light-years away. Sirius has a reputation for twinkling vigorously with flashes of pure colour. This is because it sits fairly low in the sky for mid-latitude residents, and we see it shining through a thicker blanket of refracting air. Sirius’ bright little sibling Procyon (8th) sits 25° (2.5 fist widths) to the upper left, under Gemini, in the constellation of Canis Minor (the Little Dog). It, too, is relatively close to Earth.

The Winter Football, also known as the Winter Hexagon and Winter Circle, is an asterism composed of Sirius, Rigel, Aldebaran, Capella, Castor & Pollux, and Procyon. Reaching its highest position in the southern sky at around 11 pm local time, the asterism extends from 20 degrees above the horizon to nearly overhead, with the Milky Way running vertically through it. The football is visible during evenings from mid-November to spring every year. The nearly full moon will pass through the asterism from Saturday to next Tuesday. By linking Rigel to Betelgeuse instead of Aldebaran, a large capital “G” asterism can be formed.

Watch Medusa’s Eye Brighten

Algol, also designated Beta Persei, is among the most accessible variable stars for astronomy enthusiasts. This star has been known to vary in brightness since antiquity – so the ancient Greeks decided that it represented the pulsing eye of Medusa the Gorgon, whose severed head is being held aloft by Perseus (the Hero). On a regular and predictable schedule Algol’s visual brightness dims noticeably for ten hours once every 2 days, 20 hours, and 49 minutes. This happens because a dim companion star orbiting nearly edge-on to Earth crosses in front of the much brighter main star, reducing the total light output we receive. This is known as an eclipsing binary system.

You can use nearby stars to judge Algol’s brightness. Algol normally shines at magnitude 2.1, similar to Almach (aka Gamma Andromedae) which is located a generous fist’s diameter to Algol’s lower right (or 12 degrees to the celestial west). Algol’s dimmed brightness of magnitude 3.4 is almost exactly the same as the star Rho Persei (or Gorgonea Tertia or ρ Per), the star sitting just two finger widths to Algol’s lower left (or 2.25 degrees to the celestial south).

On Wednesday, January 20 at 8:53 pm EST, Algol will arrive at minimum brightness high in the western sky. Five hours later, at 1:53 am EST, Algol will have brightened to its usual magnitude and will be positioned 22 degrees above the western horizon. Alternately, one could watch Algol grow dim on Sunday, January 17 starting at 7:04 pm EST. It will reach minimum brightness at 12:04 am.

Treats in Taurus

If you missed last week’s guide to the best sights to see in Taurus, it is posted with sky charts and some photos of objects here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory Youtube channel, where they offer free online viewing through their rooftop telescopes, including their 1-metre telescope! Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National will return on Tuesday afternoon, January 19 at 3:30 pm EST. This week, we’ll talk about Astrology and Astronomy! You can find more details, and the schedule of future sessions, here and here.

On Wednesday evening, January 20 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will live stream their monthly Speakers Night meeting. This month will feature Prof. Nassim Bozorgnia, assistant professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at York University. Her talk is entitled Searching for the Mysterious Dark Matter. Everyone is invited to watch the presentation live on the RASC Toronto Centre YouTube channel. Details are here. The RASC Toronto Centre has an archive of their past meetings and guest lectures on their YouTube Channel here.

On Wednesday evening, January 20 at 6:30 pm EDT, The University of Toronto Astronomy & Space Exploration Society (ASX) will present an online talk entitled Water, Water Everywhere? by the amazing Dr. Paul Delaney, Professor at York University’s Department of Physics and Astronomy and the inaugural Carswell Chair for the Public Understanding of Astronomy. Details are here.

On Saturday night, January 23 at 7:30 pm, RASC Toronto and the David Dunlap Observatory will present an online session called Up in the Sky. RASCals will talk about the night sky and share telescope views of objects – LIVE views, if the skies are clear! Registration and details are here.

On Sunday afternoon, January 24 from 1 to 2 pm I’m hosting an online session for RASC called Ask an Astronomer in support of the David Dunlap Observatory! We’ll explore the night sky together and answer your astronomy and space-related questions in simple language – using pictures, illustrations and planetarium software. The deadline to register is Friday January 22 at 3:00pm. Registration is here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!