The Hunger Moon Grows Bright at Night and Far Mars Holds Court in Evening while Several Planets Share Pre-dawn!

This gorgeous image of the region of sky between Taurus’ triangular face and the bright orange star Aldebaran and the blue Pleiades star Cluster was taken by Amir H. Abolfath using his Canon EOS6D camera on a Star Adventurer mount. It covers a span of sky of about 19 degrees (two fist diameters) top-to-bottom, and reveals the dust and gas of our Milky Way’s plane. The image was the NASA APOD for December 6, 2019. Amir’s gallery of images is at http://amir.torgheh.ir/

Hello, Night Sky Fans!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of February 21st, 2021 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together!

The moon will shine brightly in the night-time sky for observers around the world this week – passing through the Winter Hexagon and big star clusters, and offering terrific views of its best features in binoculars and telescopes. Meanwhile, Mars in Taurus, and Uranus in Aries, can be viewed in the evening sky while the rest of the visible planets are tucked close to the sun in the pre-dawn. Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon

For the second consecutive week, the moon will be shining brightly in the evening sky for observers all around the world. Our nocturnal nightlight will rise during the afternoon hours and then become an enticing object to view in your binoculars and backyard telescopes all night long. Let’s run through some encounters the moon will have this week, and highlight some features to look at!

Tonight (Sunday, February 21), the eastward orbital motion of the moon will carry it towards and then across the large open star cluster known as Messier 35, or the Shoe-Buckle Cluster in the constellation of Gemini (the Twins). When the sky has fully darkened in the Eastern Time zone, at about 7 pm local time, the moon will be positioned several finger widths to the upper right (or 4 degrees to the celestial west) of the star cluster. Hour by hour, the moon will approach the cluster while the diurnal rotation of the sky lifts the cluster above the moon. By the time the moon sets after 3 am local time, observers in the Eastern Time zone will see the moon positioned only a moon’s diameter below the cluster. Observers in more westerly time zones will get to see the moon pass across the cluster and leave it behind before the moon sets. The central grouping of that cluster’s stars is nearly as wide as the moon – but you won’t see the cluster in its full glory with the bright moon parked right next door. To best see Messier 35’s stars, hide the bright moon beyond the edge of your binoculars’ field of view. Or, take note that Messier 35 is located to the upper right of the medium-bright stars forming Gemini’s foot, Propus and 1 Geminiorum, and use them to look at the cluster on a night when the moon has moved away.

From Sunday night to Tuesday night, the waxing gibbous (i.e., more than half-illuminated) moon will be crossing through the giant Winter Hexagon or Winter Football asterism, which is composed of the bright stars in the constellations of Canis Major (the Big Dog), Orion (the Hunter), Taurus (the Bull), Auriga (the charioteer), Gemini (the Twins), and Canis Minor (the Little Dog) – specifically the stars Sirius, Rigel, Aldebaran, Capella, Castor & Pollux, and Procyon, respectively. After dusk, the huge pattern will stand upright in the southern sky – extending from 30 degrees above the horizon to overhead. I described and posted a diagram of the asterism and its stars here.

On Tuesday night, the moon will pass very close to the medium-bright star designated Kappa Geminorum, which marks the eastern hand of the twin Pollux. The event will make a pretty sight in binoculars and telescopes. Observers living between 38.5° N and 7° N latitude (from about Washington, DC and south to Georgetown, Guyana) can see the moon pass in front of (or occult) that star in the period surrounding 7:32 pm Eastern Time.

On Wednesday night, the almost full moon will pass just two finger widths to the upper left (or 2° to the celestial north) of the Beehive, an even larger open star cluster in Cancer (the Crab). The cluster sits close to the Ecliptic – so the moon and planets frequently buzz the Beehive. As with the Shoe-Buckle cluster, hide the bright moon beyond the top edge of your binoculars to see the “bees”.

From Thursday to Saturday, the very bright moon will cross the constellation of Leo (the Lion) and its brightest star Regulus. The moon will officially become full at 3:17 am EST (or 8:17 Greenwich Mean Time) on Saturday morning – so the moon will look just a sliver less than full on both Friday evening and Saturday evening – but the thin strip along the edge of the moon that isn’t illuminated will switch from the lower left (lunar west) side to the upper right (lunar east) side from one night to the next (because the moon’s angle from the sun will increase from 175° to 192° in 24 hours – i.e., crossing the 180° position).

When full, the moon always rises around sunset and sets around sunrise because it is opposite the sun. The February full moon always shines in or near the stars of Leo (the Lion), which is half the sky away from the sun in the stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat).

The moon has always shone down upon humans on Earth. At some point, people began to seek to understand our natural environment and to take advantage of the annual variations in the seasons to schedule planting, harvesting, hunting, and celebrating life events. The twelve (or thirteen) full moons per year acted as obvious celestial markers. The full moon’s bright light allowed people to be out and about safely at night; lighting the way of the hunter or traveler before modern conveniences like electric lights, and workers in the fields devoting extra hours to get the harvest in. By the way – those extra, thirteenth full moons, which fall into different months each year, are commonly referred to as blue moons. This year that will happen in August.

Each society around the world developed its own set of stories for the moon, and every month’s full moon now has one or more nick-names related to human spirit or the natural environment. The indigenous Anishnaabe (Ojibwe and Chippewa) people of the Great Lakes region call the February full moon Namebini-giizis “Sucker Fish Moon” or Mikwa-giizis, the “Bear Moon”. For them it signifies a time to discover how to see beyond reality and to communicate through energy rather than sound. The Algonquin call it Wapicuummilcum, the “ice in river is gone” moon. The Cree of North America call it Kisipisim, the “the Great Moon”, a time when the animals remain hidden away and traps are empty. For Europeans, it is known as the Snow Moon or Hunger Moon.

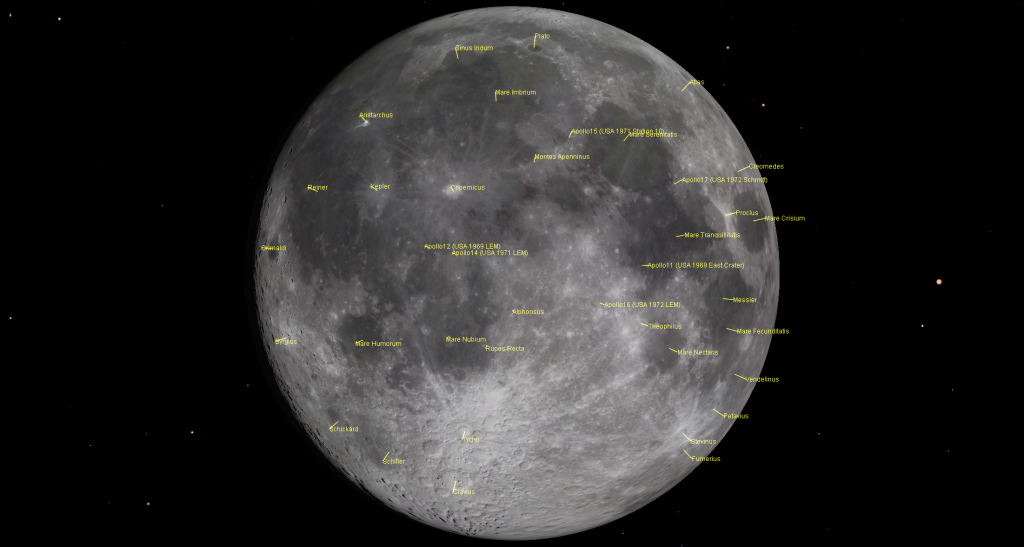

Looking at the moon through binoculars and telescopes this week will show you the tremendous difference in the way sunlight illuminates the moon, and the impact of that. Early in the week, the sun’s rays will be striking the moon from the side in the zone alongside the pole-to-pole terminator line that separates the lit and dark hemispheres. At that location, the sun is just rising over the moon’s eastern horizon. With no atmosphere to scatter light, the shadows cast by every crater rim, mountain, and ridge are a deep black – and even very small bumps and ridges are highlighted, revealing otherwise hidden features on crater floors.

As we arrive at the coming weekend, however, the moon will become fully illuminated, and the sunlight striking the moon then will be coming from directly “behind you” when you face the full moon – the same way the projector in a cinema lights up the movie screen in front of you. That sunlight is arriving straight-on to the moon’s surface, so it doesn’t generate any shadows. Every variation in brightness and colour you see on a full moon is due entirely to the moon’s geology, not its topography! Now you can easily distinguish the dark, grey basalt rocks from the bright, white aluminum-rich anorthosite rocks.

The basalts overlay the various lunar maria, Latin for “seas” – coined because people used to think they were water-filled. The maria are basins excavated by major impactors early in the moon’s geologic history and later flooded with molten rock that upwelled from the interior of the moon late in the moon’s geological history.

The much older and brighter parts of the moon are composed of anorthosite rock. Those areas are higher in elevation and are also heavily cratered – because there is no wind and water, or plate tectonics, to erase the scars of impacts. By the way, the bright, white appearance is produced by sunlight reflecting off of the crystals the rock is made of – the same sort of crystals you see in the granite countertops in Earth’s kitchens. And yes, there are coloured rocks on the moon.

Some of the violent impacts that created the craters in the highland regions also threw bright streams of ejected material long distances on top of the darker maria. We call those streaks lunar rays systems. Some rays are thousands of km in length – like the ones from the very bright 100 million-year-old crater Tycho in the moon’s southern central region.

Use your binoculars to scan around the full moon. There are large and small ray systems everywhere! There are also places where the craters blasted into the maria have tossed dark rays on to white rocks. And, since the dark basalt overlays the white, older rock below, you can find lots of craters where a hole has been punched through the dark rock, producing a white-bottomed crater!

Several of the maria link together to form a curving chain across the northern half of the moon’s near-side. Mare Tranquillitatis, where humankind first walked upon the moon, is the large, round mare in the centre of the chain. Sharp-eyes might detect that this mare is darker and bluer than the others, due to enrichment in the mineral titanium. That’s one of the reasons why Apollo 11 was sent there.

Now that you know more of the lunar terminology, here are some additional events to watch for…

On Monday and Tuesday night, look for the Golden Handle on the moon. On those nights, the terminator will fall to the left (or lunar west) of Sinus Iridum, the Bay of Rainbows. The circular, 249 km diameter feature is a large impact crater that was flooded by the same dark basalt rock that filled the much larger Mare Imbrium to its right (lunar east). Sinus Iridum looks like a rounded, handle-shape on the western edge of that mare. You can see it with sharp eyes – and easily in binoculars and backyard telescopes. The “Golden Handle” is produced because slanted sunlight is brightening the eastern (right-hand) side of the prominent, curved Montes Jura mountain range (the old crater rim) that surrounds the bay on the top and left (north and west). The rim extends into Mare Imbrium as a pair of protruding promontories named Heraclides and Laplace at the bottom and top, respectively. Sinus Iridum is almost craterless, but hosts a set of northeast-oriented dorsae or “wrinkle ridges” that are revealed in telescope views at this phase. I posted a close-up photo of the area here.

This week is also ideal for viewing the prominent crater Copernicus in eastern Oceanus Procellarum. It’s well below the Golden Handle and Mare Imbrium, and slightly to the upper left (lunar northwest) of the moon’s centre. This 800 million year old feature is visible with unaided eyes and binoculars – but telescope views will reveal many more interesting aspects of lunar geology. Several nights before the moon reaches its full phase, Copernicus will exhibit heavily terraced edges (due to slumping), an extensive ejecta blanket outside the crater rim, a complex central peak, and both smooth and rough terrain on the crater’s floor. Around full moon, Copernicus’ rather ragged ray system, which extends 800 km in all directions, becomes prominent. Use high magnification to look around Copernicus for small craters with bright floors and black haloes – caused by impacts through Copernicus’ white ejecta that excavated dark Oceanus Procellarum basalt and even deeper highlands anorthosite.

From Wednesday night onwards, look for the small, but bright, patch of the crater Aristarchus, which sits west of Copernicus in the middle of huge, dark Oceanus Procellarum. It is one of the most colourful regions on the moon. NASA detected high levels of radioactive radon there. Hmmm – coincidence?

The full, but waning moon will end this week next Sunday night among the stars of western Virgo (the Maiden).

The Planets

Mars and Uranus are the only observable planets during evening nowadays. Faint Neptune is embedded within the western twilight after sunset – and Mercury, Venus, Jupiter, and Saturn are all grouped just west of the sun in the southeastern pre-dawn sky.

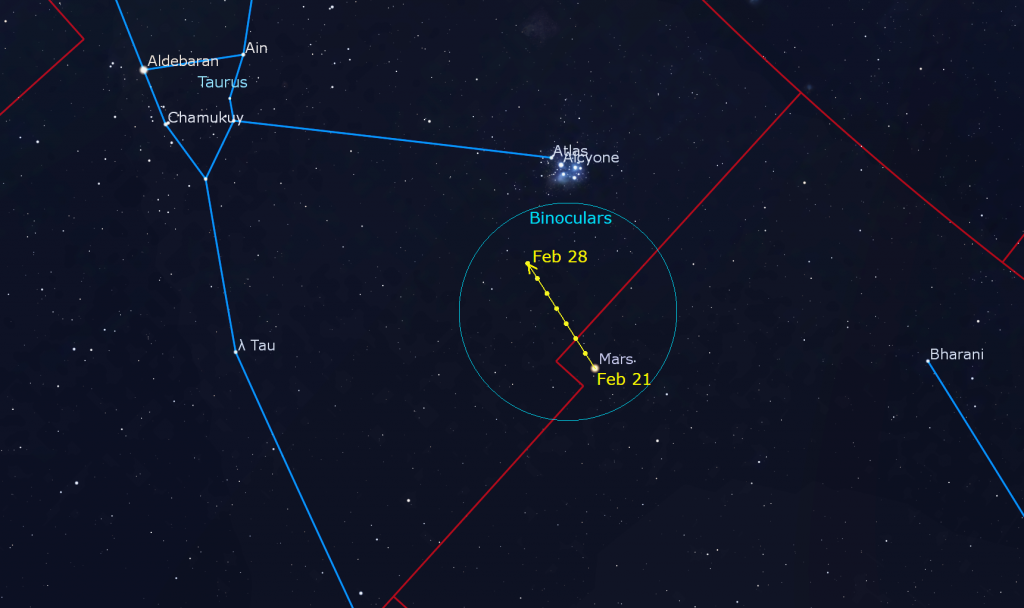

Mars was in the news this week with the successful touchdown of the Perseverance Rover, or “Percy”, and his little drone-copter Ingenuity. You can look for small, reddish Mars between dusk and almost midnight every night, but it has been getting fainter, and smaller in telescopes, with each passing week. Look two-thirds of the way up the southwestern sky at dusk. Mars will set just before 1 am local time – so be sure to take your look early, while it’s higher in the sky. Europe, India, China, and Emitrates have spacecraft at Mars right now, too – give them a wave while you’re looking up!

Mars’ rapid eastward orbital motion along the ecliptic is carrying it through Taurus. During this week, Mars will cover about four finger widths of sky (4°) on a trajectory between the bright little Pleiades star cluster and Taurus’ brightest star Aldebaran. That star will look about as bright and as red as Mars.

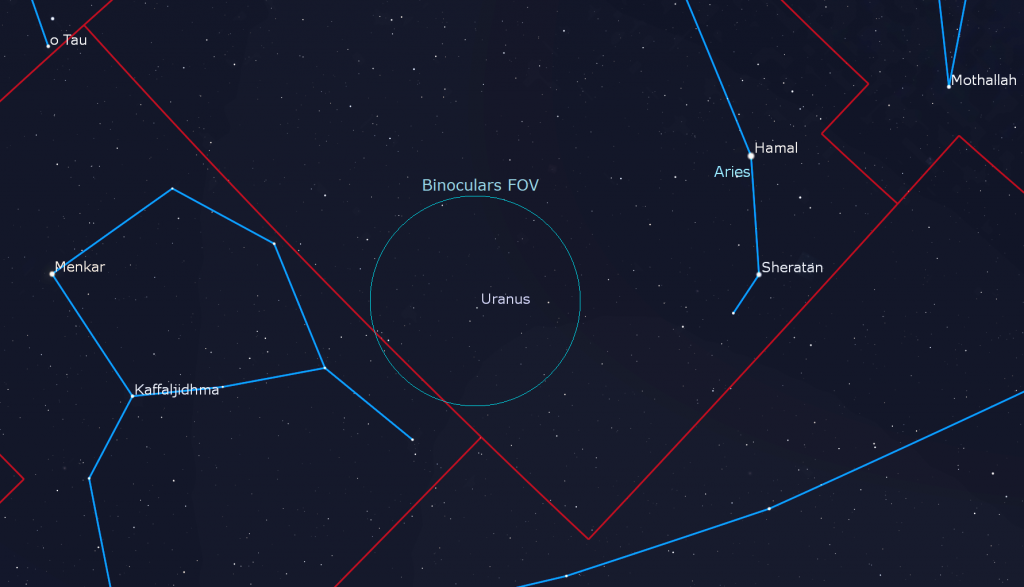

Meanwhile, dim and distant Uranus will be located about two fist diameters to Mars’ lower right (celestial west). The two brightest stars of Aries (the Ram), the magnitude 2.0 star Hamal and its slightly dimmer magnitude 2.6 neighbour Sheratan, which sits just to Hamal’s lower right, are located a fist’s diameter to the upper right (or 10 degrees to the celestial north) of Uranus. They’ll help you find the planet.

View Uranus early in the evening, too – when it’s higher in the sky and shining through less of Earth’s distorting atmosphere. In a telescope, Uranus will resemble the stars near it – but the planet won’t twinkle as much as they do, and it will show a blue-green colour.

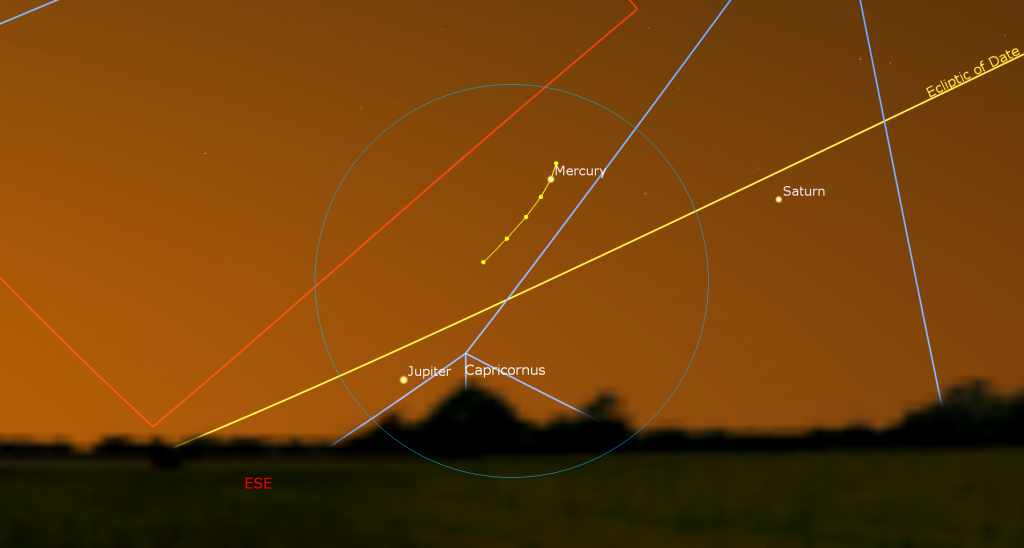

If you have a low and unobstructed view of the east-southeastern horizon, and the morning weather forecast predicts no clouds in that direction, get outside before 6:30 am local time and see how many of the planets you can spot!

Saturn and Mercury will rise together first – at about 6 am in your local time zone. Saturn will be situated less than a palm’s width to the right (or 4-5° to the celestial west) of Mercury. The speedy planet will move lower and a bit farther from Saturn during this week. Try to spot Mercury first, as it will shine almost twice as brightly as Saturn. Much brighter Jupiter will rise 20 minutes later – but the sky will have brightened more during that interval. Jupiter will be located a few degrees to the lower left of Mercury, and their separation will decrease through this week.

Venus is too close to the sun to be seen. Be sure that the sun is fully below the horizon before you search for any of the morning planets with binoculars. Note that observers who live closer to the tropics will see these planets more easily because they will be more directly above the sun and therefore shining in a darker sky before dawn.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory YouTube channel, where they offer free online viewing through their rooftop telescopes, including their 1-metre telescope! Details are here.

On Saturday night, February 27 at 7 pm, RASC Toronto and the David Dunlap Observatory will present an online session called Up in the Sky. RASCals will talk about the night sky and share telescope views of objects – LIVE views, if the skies are clear! A modest fee goes to support our ongoing efforts to deliver public programs at DDO. Registration and details are here.

On Sunday afternoon, February 28 from 1 to 2 pm I’m hosting an online session for RASC called Ask an Astronomer! We’ll explore the night sky together and answer your astronomy and space-related questions in simple language – using pictures, illustrations and planetarium software. The deadline to register is Friday February 26 at 3:00 pm. Registration is here. A modest fee goes to support our ongoing efforts to deliver public programs at DDO.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National will return on Tuesday afternoon, March 2 at 3:30 pm EST. We’re going to talk about Nebulas, Galaxies, and Star Clusters of the Messier List! You can find more details, and the schedule of future sessions, here and here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!