A Lonely Evening Jupiter Misses Mars and Venus Partying at Dawn, and Moonless Evenings Invite Peeks at Perfect Perseus!

This image of the Fossil Footprint Nebula NGC 1491 in Perseus was captured by Adam Block at Mount Lemmon Observatory in Arizona. This image is nearly one degree wide, or about finger’s width. Wikipedia

Hello, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of January 23rd, 2022 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

This week’s moonless evenings will be perfect to gaze at the sights in the winter constellations – so I lead you on a tour of Perfect Perseus. Jupiter will hang out alone in the western sky after sunset, while Mars and Venus party in the predawn. Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon

Evening skies will be moonless worldwide this week as our natural satellite works its way sunward in the pre-dawn sky. That will give stargazers dark skies to enjoy the best of winter astronomy. Tonight (Sunday) the waning gibbous moon will rise at midnight among the stars of Virgo (the Maiden). Luna will linger into morning daylight as an echo of the night.

The moon will officially reach its third quarter phase at 8:41 am EST or 13:41 Greenwich Mean Time on Tuesday morning. Third quarter moons are illuminated on the western side, towards the pre-dawn Sun. From Tuesday night onward, the moon will decrease its angle from the sun, causing it to rise closer to sunrise and display a reduced phase when you see it as you go about your morning activities.

After visiting Virgo and the Libra (the Scales) on Tuesday-Wednesday, on Thursday morning before sunrise the crescent moon will pass through the up-down line making up the three claw stars of the scorpion, Scorpius. From top to bottom, those three, 2nd magnitude, white stars are Graffias or Acrab, Dschubba, and Fang (or Beta, Delta, and Pi Scorpii, respectively. The fainter claw stars Rho Scorpii and Nu Scorpii above and below the trio add to the “danger”. Scorpius’ brightest star, reddish Antares, will twinkle to their lower left (celestial southeast) – with Mars and very bright Venus above the east-southeastern horizon.

On Saturday morning, the pretty, slender crescent of the old moon and the bright reddish dot of Mars will rise together in the southeastern sky shortly after 5 am local time – making a lovely photo opportunity when composed with some interesting scenery. The pair will be close enough to share the view in binoculars – with Venus poised a few finger widths to the moon’s upper left. Before the sky brightens, search for the magnitude 7.6 asteroid designated (4) Vesta located a binoculars’ field-width to the lower left (or 6.4 degrees to the celestial ENE) of Mars. Vesta will approach, and then pass north of, Mars in late February. Many deep sky objects of the summer Milky Way will share their scene.

Our last glimpse of the old moon, floating in twilight above the southeastern horizon, will come next Sunday morning just before sunrise.

The Planets

One bright planet left in evening – and counting…

The very bright, white dot of Jupiter, set amongst the stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), will pop into view sitting low in the southwestern sky after dusk, and then it will descend into the trees to set shortly before 8 pm local time. Binoculars and small telescopes will show you the Jupiter’s four large Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Since Jupiter’s axial tilt is a miniscule 3°, those moons always look like beads strung on a line that passes through the planet, and parallel to Jupiter’s dark equatorial belts. The moons’ arrangement varies from night to night. Once Jupiter disappears altogether in a couple of weeks, we’ll have to wait until August to see a bright evening planet (Saturn)! Jupiter and Mars won’t return until autumn.

The blue planet Neptune is following Jupiter sunward. The distant, dim planet is near the border between Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and western Pisces (the Fishes), about 1.6 fist diameters to the upper left (or 16° to the celestial east) of Jupiter. If the sky is very dark, Neptune can be seen in good binoculars and backyard telescopes. To locate it, use binoculars to find the sloped grouping of five medium-bright stars: Psi (a triple star), plus Chi, and Phi Aquarii (or ψ, X, and φ Aqr). Neptune’s non-twinkling speck will sit several finger widths to the upper left (or 3 degrees to the celestial NNE) of the top star, Phi. Viewed in a telescope, Neptune’s apparent disk size will be 2.2 arc-seconds. Try to view Neptune in early evening, while it sits higher in the sky. It’ll tough to find by 8 pm local time.

At magnitude +5.7, Uranus can be seen easily in binoculars and backyard telescopes – and even with your unaided eyes, under this week’s dark skies. Look for the planet’s small dot positioned a fist’s width to the lower left of (or 11.5 degrees to the celestial southeast of) Aries’ brightest stars, Hamal and Sheratan. Or use binoculars to locate Uranus using the closer star Mu Ceti, which sits to its lower left. Uranus is also about two fist diameters to the upper right (or 19 degrees to the celestial west-southwest) of the Pleiades star cluster. This week Uranus will be observable all evening – especially around 7 pm local time, when it will sit more than halfway up the southern sky.

Mars and much brighter Venus are now ensconced in the southeastern pre-dawn sky. This week, they’ll both rise after 5:30 am local time, with Mars positioned 1.4 fist diameters to the right of Venus. Watch for Mars’ rival, the bright star Antares in Scorpius (the Scorpion), shining well to the upper right (celestial west) of Mars. The minor planet designated (4) Vesta will be dancing between the two planets.

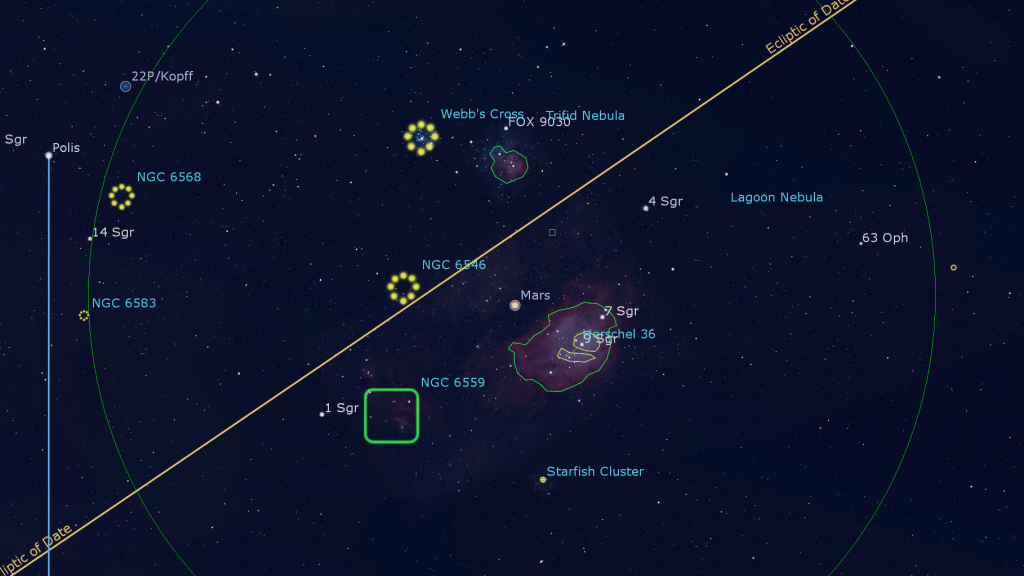

On Wednesday morning, January 26, the orbital motion of Mars will carry the planet close to several bright deep sky objects in northern Sagittarius (the Archer). The Trifid Nebula (Messier 20) and the open star cluster Messier 21 will sit a thumb’s width to the upper left (or 1° to the celestial NNW) of Mars. The Lagoon Nebula (Messier 8) with its central star cluster NGC 6530 will be positioned just to the lower right (or 0.5° to the south) of Mars. Some of the deep sky objects will be visible in binoculars under dark sky conditions, especially from tropical latitudes. Take care to turn binoculars and telescopes away from the eastern horizon well before the sun rises.

The Perks of Perseus

Last week here I introduced Perseus (the Hero) and how to locate him in the sky. This week, we’ll tour his most interesting stars and deep sky objects. Perseus is a gem of a constellation. It contains a little of everything that the deep sky has to offer – hot, young stars, cool, elderly stars, an obviously variable star, double stars, nearby and distant open star clusters, emission, reflection, and planetary nebulas, and lots of galaxies! Many of its delights can be enjoyed in binoculars – so bundle up, head outside with a chaise, and just look up!

Pointing out Perseus’ stars can be tricky because the constellation rotates around the north celestial pole. For now, let’s assume we’re outside facing south in early evening during January – so that Perseus is at the zenith, between the bright star Capella and the W of Cassiopeia (the Queen) with his head up (north) and his feet down (south). His arms extend to the left (east) and the right (west).

Mirfak or Alpha Persei (α Per) is Perseus’ brightest star. It’s a golden, F5-class supergiant star located about 510 light-years from Earth. The name Mirfak is shortened from the Arabic expression Marfik al Thurayya, “the Elbow Nearest to the Many Little Ones”, referring to the Pleiades star cluster by their Arabic name, al Thurayya. Mirfak is several thousand times more luminous than our sun and about 42 times larger. Some ancient star charts labelled Mirfak as Algenib, from Al Janb “the Side” – but that name is nowadays used for Gamma Pegasi, the southeastern star in Pegasus’ Great Square. Mirfak is at the upper right (northwestern) edge of a large and loosely scattered cluster of bright, blue-white stars known as the Alpha Persei Moving Group, the Perseus OB Association, and Melotte 20. Those stars are siblings of Mirfak – born from the same molecular hydrogen cloud about 41 million years ago – and now travelling through the galaxy together. I described them last week here.

Heading down the hero’s body on his left-hand (eastern side), the medium-bright star positioned several finger widths to Mirfak’s lower left is Delta Persei (δ Per). It’s an outlying member of the OB Association. In a telescope, Delta Persei will split into a close double star pair. Some star charts depict Delta as Perseus’ eastern shoulder. A chain of half-as-bright stars, each about a thumb’s width apart, form his arm, extending to the east and curving upwards. In order, they are c Persei, Mu Persei (μ Per), b Persei, and Lambda Persei (λ Per).

Two relatively bright open star clusters named NGC 1545 and NGC 1528 are positioned within a finger’s width of the star b Perseii – to the left and above it, respectively. Together, they are named the m & m Double Cluster. Less than a finger’s width above (north of) Lambda Persei sits a beautiful clump of glowing gas with embedded stars called the Fossil Footprint Nebula or NGC 1491. In long exposure images it reaches the size of the full moon. Several more star clusters sit above it.

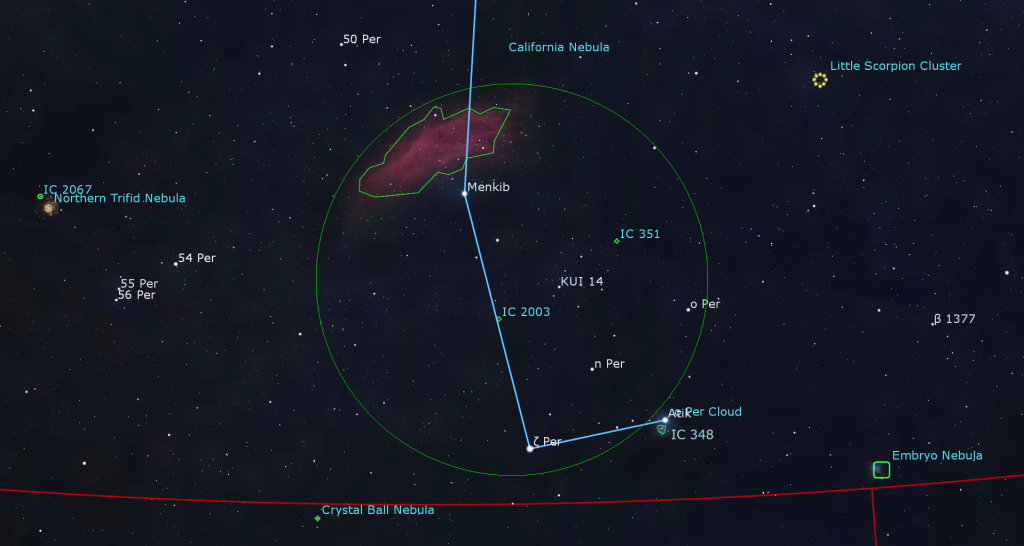

Starting back at Delta Persei, look nearly a fist’s diameter to the lower left for the star Epsilon Persei (ε Per), and then descend a few more finger widths to the less-bright star Menkib or Xi Persei (ξ Per), so named from the expression Mankib al Thurayya “shoulder of the Pleiades”. Menkib is a blue supergiant star, 12,700 times brighter than our sun. Its photosphere’s temperature of 35,000 K makes it one of the hottest stars you can see with your unaided eyes. The radiation from Menkib is causing the hydrogen gas in a nearby cloud to glow with red light, producing the gorgeous California Nebula, or NGC 1499. The elongated nebula, which stretches sideways just above Menkib, covers a patch of sky larger than 1 x 5 moon diameters! A palm’s width to the left (or 6.4 degrees to the celestial east) of Menkib is a much smaller, but brighter glowing gas region called the Northern Trifid Nebula (NGC 1579), so-named because strips of dark foreground dust splits the gas into lobes.

From Menkib we descend several finger widths south to Zeta Persei (ζ Per), a bright star that marks Perseus’ eastern foot. Zeta is about 750 light years from us. In a telescope, look for two small stars huddled together close below it – its travelling companions. Two finger widths to the right (west) of Zeta, look for the medium-bright, white star named Atik or Omicron Persei (ο Per). Its name comes from Al Atik “the shoulder” – although I see it as the wing of his sandal. Atik is part of a multiple star system. Under high magnification in a telescope it splits into a close together pair of stars. Binoculars should show you a little clump of stars below the pair, an open cluster named IC 348. A star named V718 Persei within IC 348 appears to be periodically eclipsed by an orbiting giant exo-planet every 4.7 years. Long exposure photos reveal a large halo of blue nebulosity around both Atik and the cluster. Similar to the Pleiades, the glow is bright starlight scattering from interstellar dust in the foreground. The sky just above and between Zeta Persei and Atik is sprinkled with little stars. Another pretty knot of glowing gas and stars named the Embryo Nebula (NGC 1333) is located a few finger widths to the right of Atik.

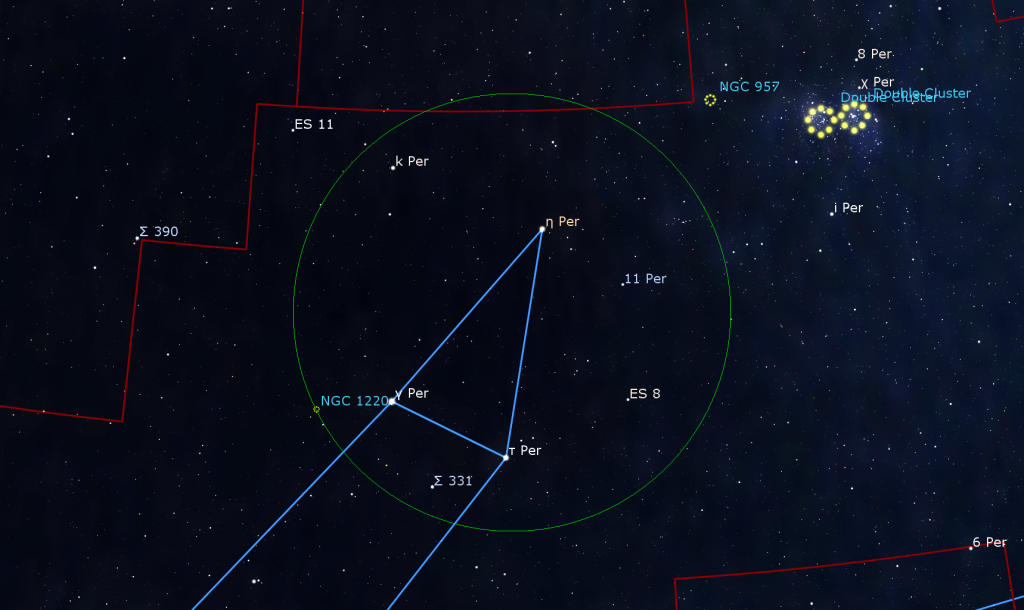

Starting back at our home base, bright Mirfak, let’s continue up the eastern side of Perseus’ head. Four finger widths to the upper right of Mirfak sits medium-bright, yellow Gamma Persei (γ Per), a sun-like star. Some charts label it Al Fakhbir or Alphecher, from the Arabic for “the Excellent One”. Gamma is an eclipsing binary star system that diminishes a little bit in apparent brightness for two weeks every 14.6 years. Think of Gamma as Perseus’ eastern eye, or ear. The less-bright, orange-tinted star parked a few finger widths to Gamma’s upper right marks the top of the hero’s head. That’s Eta Persei (η Per), sometimes called Miram. It’s located about 1,300 light-years away from us. Look for a faint white companion star nearby. Meteors from the annual Perseids Meteor Shower appear to radiate from a point in the sky near this star because Earth is traveling in that direction at the shower’s peak. The sky just to the upper right of Eta contains the bright Double Cluster I described last week here.

Descending a few finger widths from Eta, we find the hero’s western eye, or ear – the star Tau Persei (τ Per). As with Gamma to its left, Tau is a G8-class, sunlike star. It has the same familiar yellowish tint, but shines only half as brightly as Gamma. It’s another eclipsing binary system, with a period of 4.15 years. Use your binoculars to look for a star located a finger’s width to the lower left of Tau Persei. In a telescope, that star divides into a close together pair, the double star named Struve 331 or Σ331! (The name comes from father and son astronomers Friedrich Georg Wilhelm von Struve and Otto Wilhelm von Struve, who catalogued double stars.)

Continuing down Perseus’ western side brings us to Iota Persei (ι Per). It’s another yellow star, positioned about two finger widths to the right of Mirfak. Iota is one end of a long, bent row of stars, all about the same brightness, that represent Perseus’ western arm or outstretched sword. It continues with Theta Persei (θ Per) about four finger widths to the right, the widely spaced, reddish group of stars 64, 65, and 66 Andromedae a few finger widths farther on (the border with Andromeda jogs up and down in this area), and ends at the white star Phi Persei (φ Per) a palm’s width beyond them – for a total length of 1.4 fist diameters (14 degrees). Phi has a fainter reddish companion sitting just below it. A finger’s width above Phi (or 0.9 degrees to the north-northwest) you’ll find Messier 76, the Little Dumbbell Nebula. It’s a planetary nebula – the corpse of a star with the mass of our sun that blew off its outer layers at the end of its life. This little gem, 5600 light-years distant, can be seen in a backyard telescope under dark skies.

From back at Iota Persei, drop your gaze four finger widths south to yellow-orange Kappa Persei (κ Per). At 112 light-years away, it’s among Perseus’ closest stars to Earth. Its traditional name Misam comes from the Arabic miʽṣam “wrist”. It has evolved from a sunlike G-class star into a red giant fusing helium in its core. It may actually have been ejected from the Pleiades or Hyades clusters to the south! NGC 1245, a nice open cluster the size of the moon is located just a finger’s width to the left of the midpoint between Iota and Kappa. It’s nickname the Patrick Starfish Cluster comes from SpongeBob.

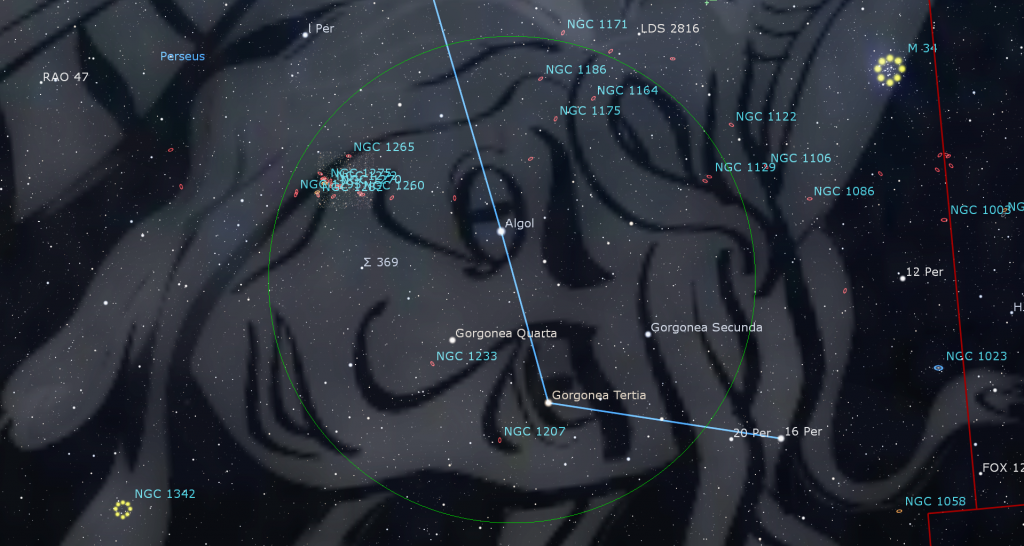

The bright star positioned a few finger widths below (or 4 degrees to the celestial south of) Kappa is Beta Persei (β Per), better known as Algol, from the Arabic Ra’s al-Ghul, which means “the Demon’s Head”. The star represented the god Horus in Egyptian mythology and was Rosh ha Satan “Satan’s Head” in Hebrew. Before we focus our attention on Algol and the stars forming Medusa’s head, aim your binoculars or telescope four finger widths to the right (celestial west) of the midpoint on the line connecting Misam to Algol and look for the big and bright open star cluster Messier 34, also called the Spiral Cluster and NGC 1039. Many of its brightest stars are arranged in curved chains, hence the name.

The area around Algol is littered with distant galaxies! A galaxy cluster named the Perseus Cluster or Abell 426 contains thousands of them, including an active peculiar galaxy named NGC 1275 or Perseus A that is the brightest object in X-ray wavelengths in the entire sky, despite it being more than 225 million light-years away! NGC 1275 and some of the galaxies near it are visible in larger backyard telescopes and long exposure photographs. The cluster is centred two finger widths to the upper left (celestial east-northeast) of Algol.

Algol is among the most accessible variable stars for beginner skywatchers. Like clockwork, this star’s visual brightness dims noticeably for about 10 hours once every 2 days, 20 hours, and 49 minutes. That happens because a dim companion star orbiting nearly edge-on to Earth crosses in front of the much brighter main star. Once the eclipse begins, the light we see steadily drops in brightness for five hours, and then it ramps up again during the second five hours – until the eclipse is over. Algol is the archetype for all eclipsing binary star systems.

Algol represents the pulsing eye of Medusa the Gorgon, whose severed head Perseus is carrying, hence its scary nickname. Yet another name for Algol is Gorgonea Prima “the First Gorgon”. The star that sits two finger widths below Algol is Gorgonea Tertia “the Third Gorgon” or Rho Persei (ρ Per). In binoculars, the star appears markedly red due to its cool, M4-class spectrum. Gorgonea Secunda “the Second Gorgon” and Gorgonea Quarta “the Fourth Gorgon” are the stars Pi Persei (π Per) and Omega Perseii (ω Per). They are located to the lower right and lower left of Algol, respectively. The four Gorgonea stars combine to form Medusa’s box-shaped head. Algol is located about 90 light-years from Earth – but the other three stars are all about 300 light-years distant.

The easiest way to detect Algol’s variability is to note how bright the star looks compared to other neighboring stars. When it isn’t dimmed, Algol is as bright as Almach, the bright star located a fist’s diameter to Algol’s right (or celestial west) in Andromeda. Although Gorgonea Tertia is somewhat variable, too – it’s pulsing due to old age – Algol shines at about the same brightness while at its minimum.

There are even more discoveries to made in Perseus (the Hero). Enjoy your exploring and tag me if you get any images of its treats!

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory YouTube channel.

On Friday, January 28 at 7:30 pm EST, RASC Mississauga Centre will stream their Speaker Night Meeting. The live, free event on Zoom will feature Dr. Lea Hirsch of University of Toronto – Mississauga discussing Here Come the Suns: The statistics and habitability of planets in binary star systems. The link and details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Samantha Jewett of RASC National return on Tuesday, February 1 at 3:30 pm EST, when we’ll talk about the gorgeous nebula that you can see and what they are. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!