Decoding Daylight Saving Time, Morning Moon Passes Planets, Mars nears the Bull’s Eye, and Gemini’s Gems!

This spectacular image by Petr Horalek od Institute of Physics in Opava shows reddish Mars (bottom centre) just below the blue Pleiades star cluster on March 3, 2021, and Mars’ “twin”, the reddish star Aldebaran above the “V” of Taurus at lower left. The red streak at the upper right is the California Nebula in Perseus. About 35 degrees of sky are shown here. NASA APOD for March 4, 2021

Hello, March Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of March 7th, 2021 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics.You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together!

The moon will spend this week visiting the pre-dawn planets on its way to New Moon on Saturday. That will leave night skies dark around the world – and ideal for exploring Gemini and the other constellations near the Winter Milky way. Mars continues to pass the Pleiades and Aldebaran – and I decode Daylight Saving Time, which starts next weekend. Read on for your Skylights!

Daylight Saving Time

For jurisdictions that employ Daylight Saving Time (or DST, for short), clocks should be set forward by one hour at 2 am local time on Sunday, March 14 – or before you go to sleep on Saturday night. In North America the “Spring Forward” will remain in effect until Daylight Saving Time reverts to Standard Time when we “Fall Back” on November 7, 2021.

For much of human history people woke with the sun and went to bed at dusk. At equatorial latitudes, where most people lived, hunted, and farmed, the length of daylight through the year doesn’t vary by a lot – so that habit worked well. But as more people settled around the world and began to use standardize working hours – especially at higher latitude locations where the days lengthened and shortened dramatically throughout the year – they were forced to use artificial light indoors when the sun wasn’t shining into windows.

In a satire he published while living in Paris in 1784, scientist/naturalist Benjamin Franklin proposed that Parisians get out of bed earlier to take advantage of the early sunrises in summer – and thereby save money on candles and oil in evening. For the same reason, during the 19th Century it became common for schools and businesses to adjust their operating hours with the seasons – but there was no standardization of the practice.

New Zealand entomologist George Hudson first proposed what became Daylight Saving Time in 1895 – but he wanted a 2-hour time shift! The idea then spread to England where prominent English builder and outdoorsman William Willett, also an avid golfer, noted that more work (and golf) could be fit into the day if the clocks were advanced during the warm months. While the British parliament toyed with the proposal for years, it was Canada that led the way!

The first city in the world to enact DST, on July 1, 1908, was Port Arthur, Ontario, Canada – followed soon after by Orillia, Ontario. The German Empire and Austria-Hungary adopted DST on April 30, 1916 – as a way to conserve coal during World War I. Britain and most of its allies, plus many European neutrals soon followed. The USA adopted DST in 1918. Except for Canada, the UK, France, Ireland, and the United States, DST was abandoned after the war; but it was re-instated during World War II and then firmly adopted as a result of the energy crisis of the 1970’s.

The inconvenience of twice-yearly clock changes has led to calls to abandon the practice. Some jurisdictions, including Ontario, Canada, are proposing to remain on DST year-round. I’d prefer to remain on Standard Time. For stargazers, the one hour change, plus the fact that sunset occurs 1 minute later each day near the March equinox, means that star parties and dark-sky observing cannot begin until much later in the evening – possibly after the bedtime of junior astronomers! Staying on DST will also mean that sundials will be permanently wrong – because noon will occur at 1 o-clock pm, and not at 12 o-clock pm.

The abbreviations for the time zones change when DST is in effect. Eastern Standard Time (EST) becomes Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) – and so on. For those who deal with the timing of astronomical events, the difference between local time and the international standard of Greenwich Mean Time (or GMT), and the astronomers’ Universal Time (UT), will decrease by one hour when DST is in effect.

Zodiacal Light

If you live in a location where the sky is free of light pollution, you might be able to spot the Zodiacal Light, which will appear during the two weeks that precede the new moon on Saturday, March 13. After the evening twilight has disappeared, you’ll have about half an hour to check the western sky for a broad wedge of faint light extending upwards from the horizon and centered on the ecliptic (i.e., below Mars). That glow is the zodiacal light – sunlight scattered from countless small particles of material that populate the plane of our solar system. Don’t confuse it with the brighter Milky Way, which extends upwards from the northwestern evening horizon at this time of year. I posted a nice photo of the zodiacal light here.

The Moon

This week will deliver moonless evening skies all around the world. That’s because our planet’s dance partner will be swinging towards the predawn sun. Moonless evenings are ideal for seeing the dimmer deep sky objects of late winter. (More on this later.)

On Monday morning, the waning crescent moon will shine prettily in the southeastern sky among the stars of eastern Sagittarius (the Archer) for a few hours before sunrise. Watch for its ghostly form leading the sun across the morning daytime sky, too.

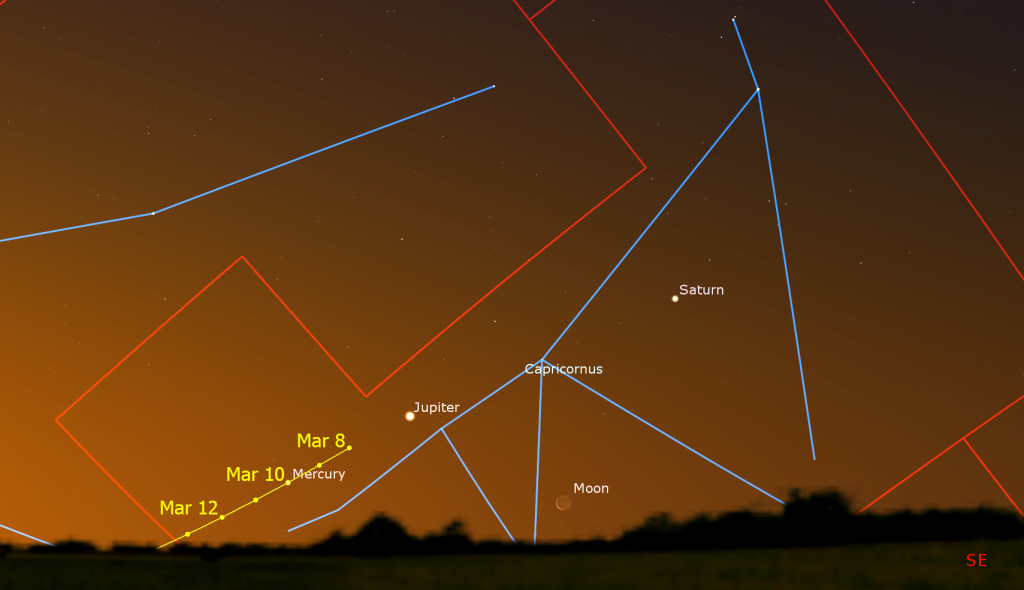

On Tuesday, the moon will begin a trip past the bright planets gathered in the predawn. When the moon rises it will be positioned less than a fist’s diameter to the right (or 8 degrees to the celestial southwest) of magnitude 0.7 Saturn. By the time the sky begins to brighten at about 6 am, much brighter Jupiter and fainter Mercury will have risen, too – forming a line to the lower left (east) of Saturn, and making a lovely photo opportunity when composed with some interesting landscape. That line of planets (plus the yet to rise sun) traces out the plane of our solar system – the ecliptic.

The moon’s visit with the bright morning planets will continue on Wednesday when the very slim crescent moon will shift east to sit below and between bright, magnitude -2.0 Jupiter and fainter Saturn. The 5° tilt of the moon’s orbit allows it to deviate by up to that amount either north or south of the ecliptic. Since the moon will be riding well south of the ecliptic this week, you’ll find it just above the horizon, and below the row of pre-dawn planets, making it harder to spot. Observers who live closer to the tropics will see a better show because the ecliptic will be more vertical there – allowing the moon and planets to shine higher, and in a darker sky, before dawn. That will be true on Thursday, too – when the moon will be located a palm’s width southeast of the planets. Unfortunately for mid-northern latitude observers, the moon will rise with the sun.

At 5:21 am EST, or 10:21 Greenwich Mean Time, on Saturday, March 13, the moon will officially reach its new moon phase. While new, the moon is positioned in space between Earth and the sun. Since sunlight can only reach the far side of the moon, and the moon is in the same region of the sky as the sun, the moon becomes completely hidden from view from anywhere on Earth for about a day. Watch for the young crescent moon shining in the western sky after sunset next Sunday.

The Planets

As I mentioned above, Saturn, Jupiter, and Mercury will be arranged in a low-angled straight line, a generous fist’s diameter in length, in the southeastern pre-dawn sky this week. Jupiter will remain in the centre of the trio. Saturn will be parked 10° to Jupiter’s upper right (celestial west). Meanwhile speedy Mercury, fresh from greatest elongation yesterday (Saturday), will be shifting sunward – carrying it down and farther to the left (celestial east) from Jupiter. Venus is hidden within the sun’s glare. It will pass the sun in superior conjunction on March 26, and then begin a long stay in the western evening sky.

The best viewing time for these planets will arrive at around 6 am in your local time zone, minutes after Mercury rises. (For safety, put telescopes and binoculars away before the sun rises.) As I described in this week’s satellite passes post, an International Space Station (ISS) will pass near those planets on Monday morning for residents of the GTA.)

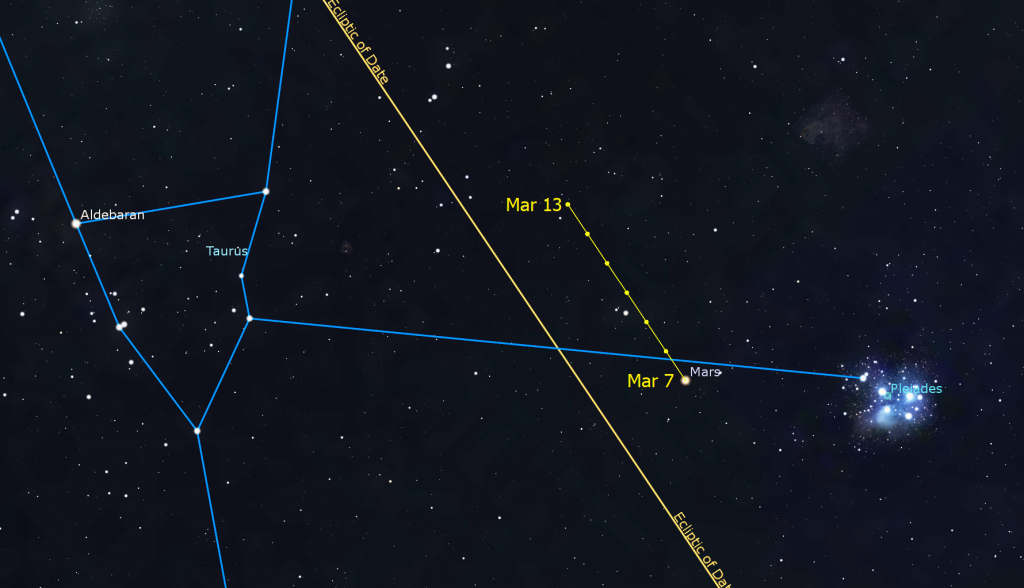

In the evening sky this week, the bright little reddish dot of Mars can be easily spotted shining near its twin – the slightly brighter, reddish star Aldebaran. The duo will be located high in the western sky after dusk. Mars’ eastward orbital motion is taking it higher and closer to Aldebaran each night. Tonight (Sunday) Mars will be a fist’s diameter to the right (or 10° to the celestial northwest) of the star. By next Sunday night, Mars will be a generous palm’s width to the right and slightly higher than Aldebaran. (That’s 8° to the celestial north.)

As I mentioned last week, Aldebaran, the brightest star in Taurus (the Bull), sits at the upper left corner of a prominent “V” of stars. That’s the Hyades star cluster, one of the closest clusters to our sun. Together they make up the triangular face of the bull. View them in binoculars, and look for even more stars – many of them close-together double stars! While you are checking out Mars, look for the Pleiades star cluster, also known as Messier 45, the Seven Sisters, the Hole in the Sky, and Subaru, positioned to Mars’ lower right. The planet and cluster will fit within the field of view of your binoculars for most of this week.

The only other planet currently available to view during evening is distant Uranus. The planet can be seen with your unaided eyes on a dark night, and quite easily in binoculars and backyard telescopes. Uranus is currently located about 2.5 fist diameters below (or to the celestial west of) Mars. The star Hamal in Aries (the Ram) is the brightest star in the lower western sky. A slightly dimmer star named Sheratan sits a few finger widths below it. Next, search the sky about two fist diameters to their left (celestial south) for the medium-bright star Menkar in Cetus (the Whale). Uranus will be a small, bluish dot parked roughly midway between Sheratan and Menkar. View Uranus as soon as it gets dark, when it’s higher in the sky and shining through less of Earth’s distorting atmosphere. In a telescope, Uranus will resemble the stars near it – but the planet won’t twinkle as much as they do, and it will show a blue-green colour.

This will be another good week to look for the asteroid designated (4) Vesta. We’re only a few days past its brightest appearance for the year (magnitude 5.8) – so it’s well within reach of your unaided eyes from a dark sky location, and in binoculars and small telescopes from the suburbs. Vesta is in the eastern evening sky in Leo (the Lion), approximately a thumb’s width to the upper left (or 1.5 degree to the north) of Chertan, the bright star that marks the lion’s rear haunches. Vesta will shift higher along the left side of Chertan for a number of nights.

Winter Constellation Treats for Dark Nights

The moonless nights this week will be ideal for looking at the best of the winter Milky Way – especially if you can escape the lights of the city. Even if you are limited to driveway stargazing, there is plenty to discover.

In the past couple of months, I have posted detailed tours of the major winter constellations – with names and fun facts about the bright stars and where to see the clusters and nebulas in them. If you missed last week’s tour of the bright star Sirius and its home constellation Canis Major (the Big Dog), I posted it with sky charts and pictures here. My earlier tours include Orion (the hunter) here, Taurus (the Bull) here, and Auriga (the Charioteer) here.

Here are some gems in Gemini (The Twins). In mid-evening during early March, the zodiac constellation of Gemini (the Twins) is positioned high in the southern sky, to the upper left of Orion (the Hunter). Gemini is dominated by the bright stars Castor and Pollux, which mark the twins’ heads. At first glance, those two stars look alike – but they are actually somewhat different in brightness and colour. Castor is a white, magnitude 1.56 star of spectral class A1. A backyard telescope will resolve it into a fine double star with a separation of 5.2 arc-seconds – but the system is actually composed of six stars located 51 light-years from our sun! Castor is always on the right-hand (western) side of the constellation when the twins are standing upright.

Pollux, the star marking the head of the more easterly (left-hand) twin shines at magnitude 1.17, making it slightly brighter than Castor. Pollux is a yellow giant star located 34 light-years from the sun. It is known to be orbited by a large, hot-Jupiter-style exoplanet that has been assigned the name Thestias.

The very bright orange star Betelguese in Orion is located about three fist diameters to the lower right (or 33° to the celestial southwest) of Castor and Pollux. Two medium-bright stars sit about midway between Castor and Pollux and Betelgeuse. Magnitude 3.5 Wasat (Delta Geminorum) marks Pollux’ waist, and the yellowish, magnitude 3.1 star Mebsuta (Epsilon Geminorum) defines Castor’s waist.

A row of widely spaced stars occupy the sky between Wasat and Mebsuta, and Betelgeuse. Those represent the feet of Gemini. At lower left (southeast) is warm white Alzirr or Xi Geminorum (ξ Gem). Next is white Alhena or Gamma Geminorum (γ Gem). To its upper right is dimmer Nucatai or Nu Geminorum (v Gem). And Castor’s westerly feet are made up two reddish, M-class stars named Tejat Posterior and Tejat Prior or Propus – plus a fainter “toe” star designated 1 Geminorum .

Both of the twins of Gemini dip their toes into the Milky Way, so the constellation includes many deep sky gems to look at. The sky to the upper right (northwest) of Propus hosts Messier 35, a beautiful, bright open star cluster composed of more than 100 brighter stars. Some star maps label it as the Shoe-Buckle Cluster. You can see Messier 35 in binoculars if the sky is dark. A fainter and more distant cluster designated NGC 2158 sits only a pinky finger’s width below (southwest of) Messier 35. A faint, but large nebula called the Jellyfish Nebula (or IC 443) is located between Tejat Posterior and Propus.

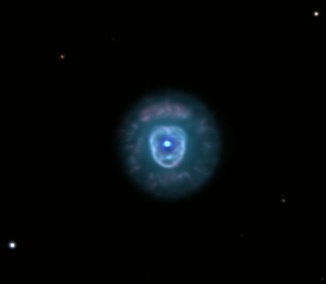

The Parka Nebula (also designated NGC 2392) is a spectacular planetary nebula visible in backyard telescopes. But use high magnification because it’s tiny – like a distant planet! This corpse of a former sun-sized star actually resembles a face surrounded by a fur-lined parka. The magnitude 9.1 object sits a little more than 2 finger widths to the left (southeast) of Wasat. Another lovely open star cluster designated NGC 2420, and sometimes called the Twinkling Comet Cluster, is located two finger widths to the left (or 2.25° to the celestial northeast) of the Parka. The easiest way to find it is to look 4 finger widths to the lower left (celestial east) of Wasat.

A brighter nebula called the Monkey Head (NGC 2174) is located two finger widths below (or 2° to the celestial south-southwest of) Propus, within the boundaries of Orion. And several more bright clusters and nebulas are located a few finger widths to the lower right of Alzirr, in northern Monoceros (the Unicorn).

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory YouTube channel, where they offer free online viewing through their rooftop telescopes, including their 1-metre telescope! Details are here.

On Friday, March 12 at 2 pm, NativeSkywatchers.com will present a free online broadcast called Two Eyed Seeing: Hawai’ian Indigenous Astronomy & NASA Moon to Mars. The session presenters are Kalepa Baybayan, Lisa Barnard, Barbara Sarbin, Jacqueline Ramirez, and Annette S. Lee – with school children from the Volcano School of Arts & Sciences in Volcano, Hawai’i. Supporting organizations are Native Skywatchers, ‘Imiloa Astronomy Center, Hokule’a, and NASA Next Gen STEM. Registration is here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National will return on Tuesday afternoon, March 16 at 3:30 pm EST. We’re going to talk about how astronomy has influenced religious festivals and traditions! You can find more details, and the schedule of future sessions, here and here.

On Sunday afternoon, March 28 from 1 to 2 pm I’m hosting an online session for RASC called Ask an Astronomer! We’ll explore the night sky together and answer your astronomy and space-related questions in simple language – using pictures, illustrations and planetarium software. The deadline to register is Friday, March 26 at 3:00 pm. Registration is here. A modest fee goes to support our ongoing efforts to deliver public programs at DDO.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!