Groundhogs Have a Happy Lunar New Year, Young Moon Meets Jupiter, Mars Moves Past Messiers, and Winter Way Wonders!

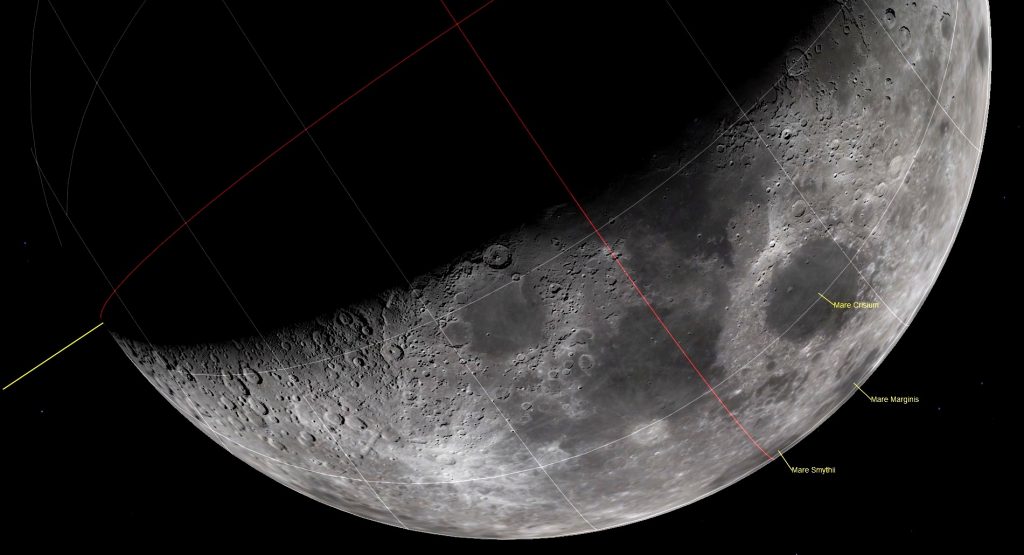

This amazing image of the young crescent moon, which triggered the Lunar New Year, was captured by Michael Watson from mid-town Toronto on February 19, 2015 at 6:37 pm EST, when the Moon was 23 hours 48 minutes past its new phase. Such moons are difficult to see it and to photograph. Happy Lunar New Year! Michael’s galleries of images can be viewed at https://www.flickr.com/photos/97587627@N06/

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of January 30th, 2022 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

With the new moon occurring on Tuesday, this week will host both the start of Lunar New Year and Groundhog Day – the midpoint of winter! Later, the young crescent moon will join lonely Jupiter in the western sky after sunset. Meanwhile, Mercury will join the Mars and Venus party in the predawn, and Mars will brush pass some Messier objects. I also tour the winter Milky Way and mention a comet in Pisces for telescope-owners. Read on for your Skylights!

Lunar New Year and Lunisolar Calendars

“Xīn Nián Kuài Lè!” 新年快乐! It’s Lunar New Year for many Asian countries, including China, Korea, and Vietnam!

Unlike our Western Gregorian calendar, a lunisolar calendar uses the 29.53-day cycle of the moon’s phases to define the months of the year – usually starting each month when the new moon phase occurs, or on the day when the young crescent moon is first glimpsed after sunset. The placement of those months is anchored to a solstice or equinox. Since solstices and equinoxes are Earth-Sun phenomena, and completely independent of the moon’s phases, lunisolar calendars drift compared to our Gregorian system. And, because the moon runs through its cycle 12.37 times per year, every second or third lunisolar year requires an extra 13th intercalary or “leap” month.

The Chinese lunisolar calendar places the December solstice into the eleventh month – causing the first month of the subsequent year to begin about two months later – on the new moon that occurs somewhere between January 21 and February 20 on our calendar. Most of the time, that moon phase lands in early February.

When the moon officially reaches its new moon phase on Tuesday at 12:46 am EST (or 05:46 Greenwich Mean Time), it will trigger the Lunar New Year observed in many Asian countries. Since that new moon happens on Tuesday, Beijing-time, too – that will be the first day of Chinese New Year holiday celebrations worldwide. It is also the first day of the Spring Festival 春节, or Chūn Jié (“CHWUN-jee-EH”), which ends with the Lantern Festival on the full moon two weeks later. Asian families will kick things off early by celebrating New Year’s Eve, Monday night, with a meal together. In Vietnam, the new year is called Tết, short for tết nguyên đán, meaning “Festival of the First Morning of the First Day”. Koreans celebrate Seolla, from Eumnyeok Seollal “lunar new year”. Japan switched to our western Gregorian new year in 1873.

Happy Year of the Tiger! The Chinese use a zodiac system – but their version doesn’t relate to the sun’s journey along the ecliptic, or even to any of the animal constellations. Instead, their zodiac preserves the sense of that word from the Ancient Greek expression zōdiakòs kýklos (ζῳδιακός κύκλος), “cycle of small animals”. They assign an animal and its attributes to each year in a repeating 12-year cycle. That interval may have arisen from the 11.85-year orbital period of Jupiter!

The order of the animals is said to have been determined by a great race to become the guards of the Jade Emperor – with their rank determined by the order in which the animals arrived at the finish line – the palace gates. The race involved both running and swimming. The mighty ox was a shoe-in to win the race. But the rat woke up early on race-day and took the lead. Arriving at the river, he feared to cross it. When the ox arrived, the rat jumped onto the gentle ox’s back and hitched a ride across. Upon reaching the opposite shore, the little rascal jumped off of the tired ox and raced ahead to win the race, leaving the ox with second place! Did he cheat – or was he clever, and worthy to be senior-most of the guards?

2022 is the third year of the current cycle, named for the third-place finisher, the tiger. When asked their age, Chinese people will commonly answer with the animal of the year they were born in. In traditional Chinese astronomy, the Jade Emperor’s Palace was represented by the stars of Ursa Minor (the Little Bear), including the pole star, Polaris.

The Chinese celebrate the New Year with red decorations and firecrackers because, stories say, long ago a mythical beast called Nian was terrorizing rural villages. After many years, an old man declared he would deal with Nian while the rest of the villagers hid during the night. He scared the beast away by hanging red paper around the village and making loud noises. Henceforth, when New Year was approaching, people would wear red clothes, hang up red lanterns, place red scrolls on windows and doors, and use firecrackers to frighten away the Nian. It never bothered the village again.

The Nisga’a indigenous group of British Columbia traditionally celebrate their new year when the crescent moon first appears after its new phase in February or March. Their celebration is called Hobiyee, a name derived from the expression “Hobixis Hee!”, which means “the moon is in the shape of the hoobix”, the bowl of the Nisga’a traditional wooden spoon. The young moon’s orientation after sunset, with its horn-tips pointing upwards, resembles a celestial scoop – ready to be filled with an abundance of salmon, river saak (candlefish), berries, and more. Children gleefully run about with their arms curved upwards, pretending to be the moon. The first month of the Nisga’a year is called Buxw-laks, where buxw means “to blow about” and laḵs means “needles” – a sure sign of winter’s end.

Wednesday is Groundhog Day

Hey – Wednesday morning, February 2 is Groundhog Day! A cloudy day supposedly augurs for an early spring. But why does it fall on February 2 each year? That date signifies one of the four so-called cross-quarter days, which are the midpoints between the solstices and equinoxes. February 2 is about midway between the winter solstice and the vernal equinox – so we can expect the weather to start being more spring-like and less winter-like afterwards, whatever your local groundhog or other subterranean rodent sees. If an early spring means clear night skies, Astronomers are all for it!

You cannot merely divide our 365.25-day year into four 91.3-day-long seasons and then count half that many days to reach the cross-quarter points. Planets with elliptical orbits move faster when they are closer to the sun and slower when they are farther away. Since Earth is moving more slowly at aphelion, in early July, summers in the Northern Hemisphere are about five days longer than winters. And winters are a couple of days shorter than 91.3. The timing of solstices and equinoxes can vary by 18 hours, so their dates aren’t always the same. The true mid-point of winter in 2022 will occur at 3:37 pm EST (or 20:37 Greenwich Mean Time) on Thursday, February 3. But someone decided to fix Groundhog Day on February 2 – I guess to allow the media to plan their coverage.

On February 2, Roman Catholics celebrate Candlemas, which marks the 40th and final day of the Christmas-Epiphany period. In contemporary paganism, the day is called Imbolc, a traditional time for initiations. Gaelics observe the traditional festival of Saint Brigid of Kildare. The other three cross-quarter days are May Day (Beltane) on May 1, and Lughnasath or Lammas on August 1, and Samhain on November 1. I think you can guess which spooky “holiday” that last one connects to. Anyway – I guess we Canadians should cross our fingers and hope for cloudy skies on Wednesday.

Have you noticed that the sky is brighter at dinner time nowadays? At this time of year in mid-northern latitudes, the sun sets about 2 minutes later every night and rises a minute earlier in the morning – dramatically lengthening our daylight hours with each passing week.

Hey – Wednesday morning, February 2 is Groundhog Day! (See what I did there? J)

The Moon

At 12:46 am EST or 05:46 Greenwich Mean Time on Tuesday, the moon will officially reach its new moon phase. At that time our natural satellite will be located approximately 5.1 degrees south of the sun, in Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). While new, the moon is travelling between Earth and the sun. Since sunlight can only reach the far side of a new moon, and the moon is in the same region of the sky as the sun, our natural satellite becomes completely hidden from view for about a day – in this case, today (Sunday) and tomorrow.

The moon will have entered the western sky after sunset on Tuesday – but it will still be too close to the sun to be easily spotted. If you do see it, give yourself a pat on the back. Catching a glimpse of the moon when it’s less than 24 hours old is an accomplishment!

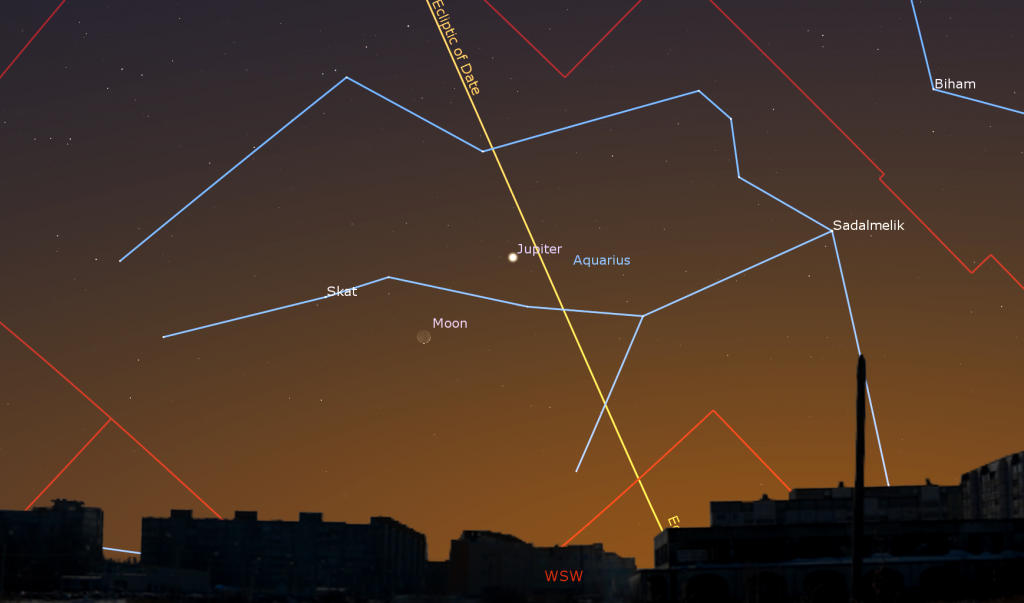

From Wednesday onward, the moon will be easy to spot – and to view in binoculars and backyard telescopes during early evening. On Wednesday, the very thin crescent of the young moon will shine several finger widths to the lower left (or 4.6 degrees to the celestial SSW) of the bright planet Jupiter; close enough for them to share the view in binoculars, which should also reveal Jupiter’s own Galilean moons! The duo will set around 7 pm local time; but try to view them as soon as the sky begins to darken, when they will be higher, and shining through less distorting atmosphere.

For the rest of the week, the pole-to-pole terminator that divides the moon’s lit and dark hemispheres will advance across its face, causing us to see the moon wax in illuminated phase. The effect is produced by the orbiting moon’s steadily increasing angle from the sun for the two weeks following new moon. It shifts east by about its own diameter every hour, and by about 12 degrees (or 1.2 outstretched fist widths) each night. (After full moon, the angle decreases, producing the moon’s waning phases.)

The sunlight arriving at the moon along the terminator is nearly horizontal, so it throws long shadows westward from every bump, hill, mountain, and crater rim, and it fills even the shallow craters with inky blackness. There is no atmosphere on the moon to scatter light and soften shadows. The scene varies night over night, and even hour by hour – so keep your telescope handy, and check in regularly.

The moon will spend Thursday evening, still in Capricornus, but now to the upper left (celestial east) of Jupiter. On Friday, Saturday, and Sunday night the moon will swim along the crooked border between Pisces (the Fishes) and Cetus (the Whale). Look for the bright stars of the Great Square of Pegasus shining to the moon’s right (celestial north).

Due to its orbital inclination (or tilt) and its ellipticity (or out-of-roundness), the moon rocks up-and-down and rolls left-to-right up by to a half-dozen degrees while keeping the same hemisphere pointed towards Earth at all times. Over time, this lunar libration effect lets us see 59% of the moon’s total surface without leaving the Earth. You can observe libration yourself by noting the way major features move toward and away from the limb of the moon, and up and down.

Mare Crisium “the Sea of Crises” is a 556 km diameter basin that is easy to see using your unaided eyes, and in binoculars, and telescopes. It is located near the right-hand (eastern) edge of the moon, just north of the moon’s equator. On Sunday night, libration will shift Mare Crisium farther from the moon’s edge. On the same evening, look closely for two dark patches positioned between Mare Crisium and the moon’s edge. Those maria, named Mare Smythii and Mare Marginis, are difficult to see unless the moon’s eastern limb is rotated towards Earth. Let me know if you see them!

The Planets

Going once, going twice…

Jupiter’s very bright, white dot, set amongst the stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), will pop into view above the southwestern horizon as the sky darkens after sunset. Then it will descend into the trees to set around 7 pm local time. Binoculars and small telescopes will show you the Jupiter’s four large Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Since Jupiter’s axial tilt is a miniscule 3°, those moons always look like beads strung on a line that passes through the planet, and parallel to Jupiter’s dark equatorial belts. The moons’ arrangement varies from night to night.

Once Jupiter disappears altogether in a week or two, we’ll have to wait until August to see a bright evening planet – Saturn! Jupiter and Mars won’t return until autumn. Speaking of Saturn the ringed planet will pass the sun in solar conjunction on Friday. It will appear very low in the twilit southeastern pre-dawn sky – approaching brighter Mercury from the east – on the last few mornings of February.

The blue planet Neptune is following Jupiter sunward. The distant, dim planet is near the border between Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) and western Pisces (the Fishes), about 1.6 fist diameters to the upper left (or 16° to the celestial east) of Jupiter. If the sky is very dark, Neptune can be seen in good binoculars and backyard telescopes. To locate it, use binoculars to find the sloped grouping of five medium-bright stars: Psi (a triple star), plus Chi, and Phi Aquarii (or ψ, X, and φ Aqr). Neptune’s non-twinkling speck will sit several finger widths above (or 3 degrees to the celestial ENE) of the top star, Phi. Viewed in a telescope, Neptune’s apparent disk size will be 2.2 arc-seconds. Try to view Neptune immediately after dark, while it sits higher in the sky. It’ll be tough to find by 6:30 pm local time. On Thursday night, the crescent moon will share the binoculars with Neptune and those stars.

At magnitude +5.8, Uranus can be seen easily in binoculars and backyard telescopes – and even with your unaided eyes, before the moon waxes too bright, or moves too close to it next Sunday. Look for the planet’s small dot positioned a fist’s width to the lower left of (or 11.5 degrees to the celestial southeast of) Aries’ brightest stars, Hamal and Sheratan. Or use binoculars to locate Uranus using the closer star Mu Ceti, which sits to its lower left. Uranus is also about two fist diameters to the upper right (or 19 degrees to the celestial west-southwest) of the Pleiades star cluster. This week Uranus will be observable all evening – especially around 7 pm local time, when it will still sit more than halfway up the southern sky.

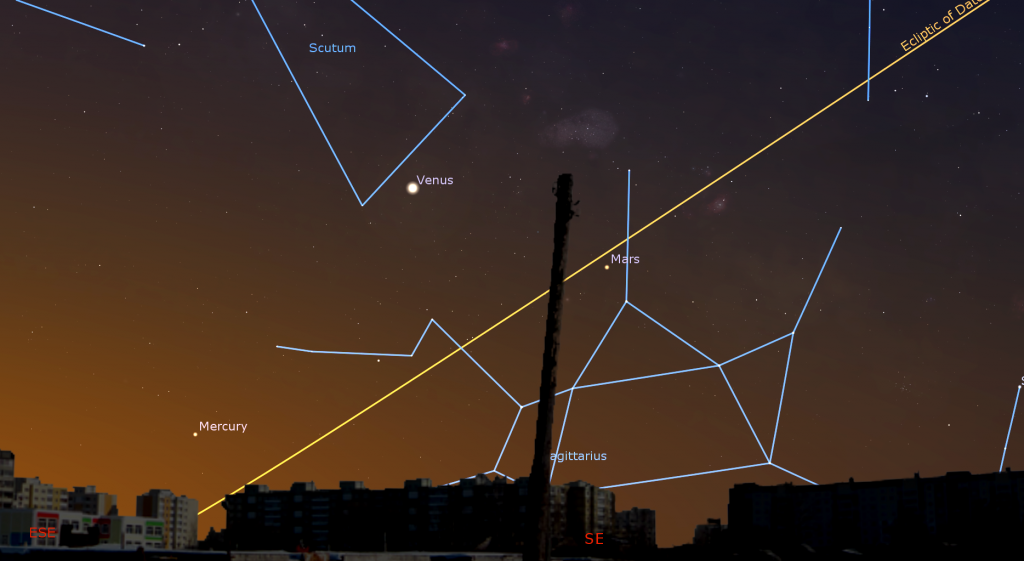

Reddish Mars and much brighter, whiter Venus are now ensconced in the southeastern pre-dawn sky. This week, they’ll both rise at about 5 am local time, with Mars positioned a fist’s diameter to the right of Venus. Watch for Mars’ rival, the bright star Antares in Scorpius (the Scorpion), shining well to the upper right (celestial west) of Mars. The minor planet designated (4) Vesta will be dancing below and between the two planets. Mars will close to within a palm’s width of Venus after mid-February.

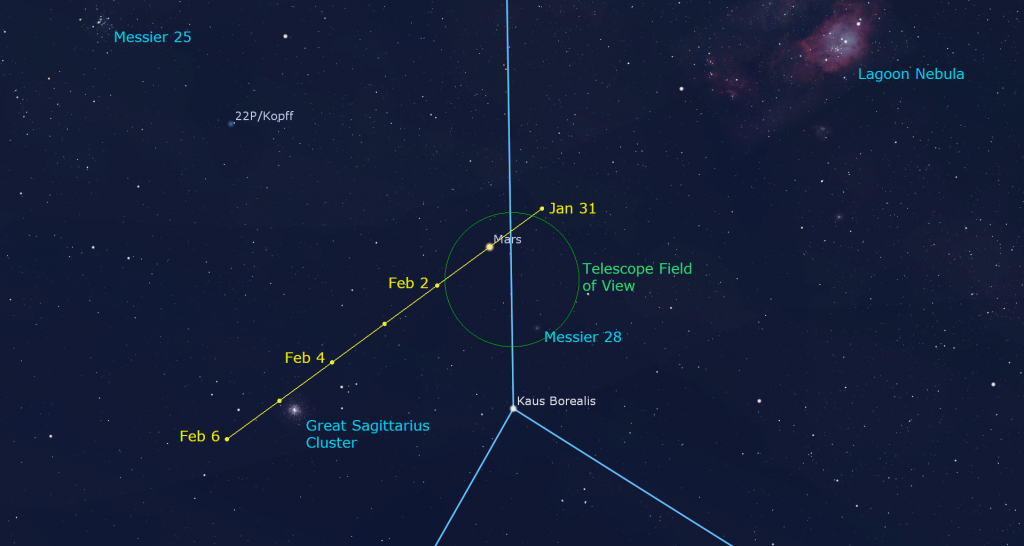

In the southeastern pre-dawn sky from Monday to Wednesday, the orbital motion of Mars will carry the planet past the globular star cluster known as Messier 28. The cluster sits just above the star, Kaus Borealis, which forms peak of the lid of the teapot-shaped star pattern of Sagittarius (the Archer). Mars and M28 will be binoculars-close for about a week – but at closest approach on Tuesday, Mars will shine only a finger’s width above (or 1 degree to the celestial north of) the cluster, allowing both objects to share the view in a backyard telescope. To see the cluster more easily, try to view the duo before the sky begins to brighten. Observers at southerly latitudes will have a better view of the scene because Mars and Messier 28 will be higher, and in a darker sky. Take care to turn binoculars and telescopes away from the eastern horizon well before the sun rises.

On Saturday morning, February 5, Mars will move through the outskirts of the large, bright globular star cluster known as the Great Sagittarius Cluster and Messier 22. The meeting will make for a terrific telescopic photo opportunity. Messier 22 is located just two finger widths to the left of Kaus Borealis. Mars and M22 will share the view in a backyard telescope from Friday to Sunday, February 6; but at closest approach on Saturday, Mars will sit only 0.2 degrees to the celestial north of the cluster. As before, try to view the duo before the sky begins to brighten.

At around 6:15 am local time after mid-week, look just above the horizon for Mercury shining 1.4 fist diameters to the lower left of Mars and Venus.

Comet Alert

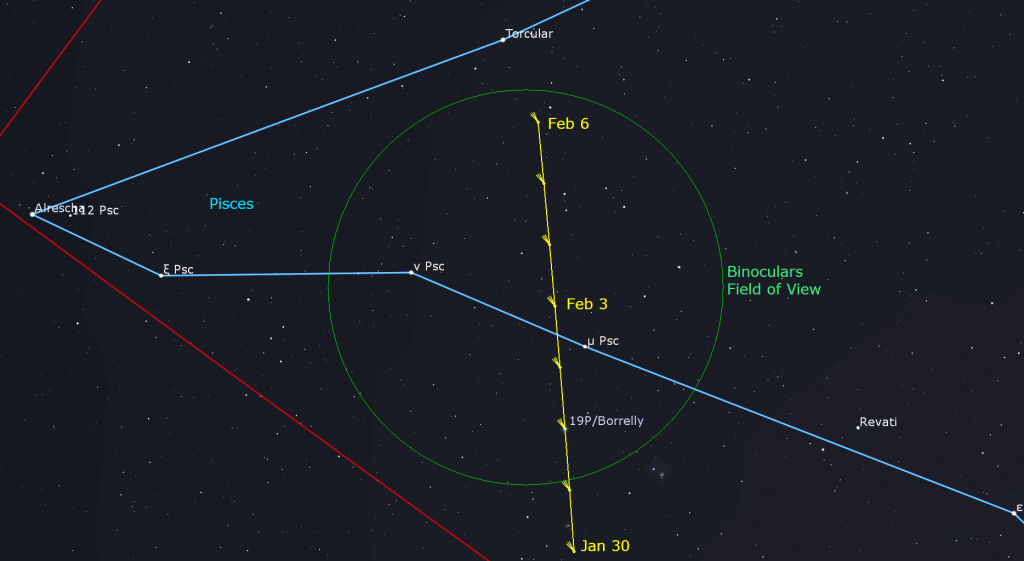

A periodic comet named 19P/Borrelly is currently visible as it travels north-easterly through Pisces (the Fishes), which sits halfway up the southwestern sky after dusk. It should reach maximum brightness of about magnitude 9 while at perihelion on Tuesday – making this comet a target for best for telescope-owners. During the first part of this week, the comet will be travelling upwards each night towards the medium-bright star Mu Piscium. It will pass less than a finger’s width to the left (celestial south) of that star on Wednesday, and then continue higher, through the V of Pisces’ stars.

Wending the Winter Milky Way

Our solar system sits inside the vast flattened disk of our galaxy, about one-third of the way towards the outer edge. That allows the faint band of the Milky Way, composed of countless stars in our galactic disk, to be traced in a huge circle around the sky. The core of the galaxy, and therefore most of its stars, is visible on summer nights. But the galaxy’s outer rim sits in the opposite direction – gracing our winter evening skies. Except for a period in late spring when the Milky Way drops to the horizon, there’s always a part of it visible in the night sky.

On a clear night this week, head outside to an open area away from city lights and look for the outer reaches of the Milky Way. It rises out of the southeastern horizon just to the left (east) of the very bright star Sirius in Canis Major (the Big Dog), and then it gradually diminishes in intensity as you follow it higher, passing between Orion (the Hunter) and Gemini (the Twins), and then just beyond the horn tip stars of Taurus (the Bull).

The point in the evening sky that sits directly opposite our galaxy’s core is located four finger widths to the lower left (or 4.3° to the celestial east) of the moderately bright star named Alnath (or Elnath), which represents Taurus’ higher horn tip. That star is shared by the constellation of Auriga (the Charioteer). In the rough ring of stars that form Auriga, Alnath sits opposite from the very bright, yellow star Capella, which is almost directly overhead at 8 pm local time.

The Milky Way should be visually dimmest near Alnath – but it isn’t. That’s because our galaxy has a non-uniform structure of spiral arms wrapping around its central core, and also because dark gas and dusk randomly concentrated within the plane of the galaxy blocks (or extinguishes) starlight. In visible wavelengths, our Milky Way’s dimmest point is actually within the constellations next to Auriga – between Perseus (the Hero) and Camelopardalis (the Giraffe).

To finish following the Milky Way across the winter evening sky, turn around and face northwest. In February, Perseus sits high in the northwestern sky, above the distinctive M- or W-shaped constellation Cassiopeia (the Queen). Cassiopeia will be dangling in an up-down orientation. The Milky Way is less intense here, but it strengthens again as we trace its thickening disk downward down through Cassiopeia and then lower, past her husband, Cepheus (the King). If your horizon is low and open, you might catch a glimpse of the bright star Deneb, which marks the tail of Cygnus (the Swan). Although much broader there, the Milky Way is darkened by a lot more dust and gas.

Many of the famous Messier List objects sit on or near the Milky Way because they are features within our galaxy. But looking above and below the plane of the Milky Way (that’s to the left or right of it at this time of year), will reveal other cities of stars – separate galaxies far beyond our own. The brightest and easiest one to see is the great Andromeda Galaxy, also known as Messier 31. It is located only 15° (or 1.5 outstretched fist widths) to the left of Cassiopeia’s bottom half. Before the moon gets too bright, bundle up and head out to enjoy the sights – if your skies are clear!

Deep Peeks into Perseus

Two weeks ago here I introduced Perseus (the Hero) and how to locate him in the sky. Last week, I toured you through his stars and other treats here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory YouTube channel.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Samantha Jewett of RASC National return on Tuesday, February 1 at 3:30 pm EST, when we’ll talk about the gorgeous nebula that you can see and what they are, and we’ll help you get started on earning your Messier Objects observing certificate. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

On Wednesday evening, February 2 at 7:30 pm EST, the RASC Toronto Centre will live stream their monthly Recreational Astronomy Night Meeting at https://www.youtube.com/rasctoronto/live. Talks include The Sky This Month, the Newcastle Observatory, and an app for logging your observations. Details are here.

On Thursday, February 3 at 8 pm EST, the Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics at the University of Toronto will stream their AstroTour. The live free event will feature PhD Candidate Taylor Kutra discussing Why haven’t I heard of her? Stories of Women in Astronomy. Details and the YouTube link are here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!