Midnight Mars and Merry Perihelion, Bright Planets near Dawn and Dusk, but a Full Oak Moon Squashes Quadrantids Meteors!

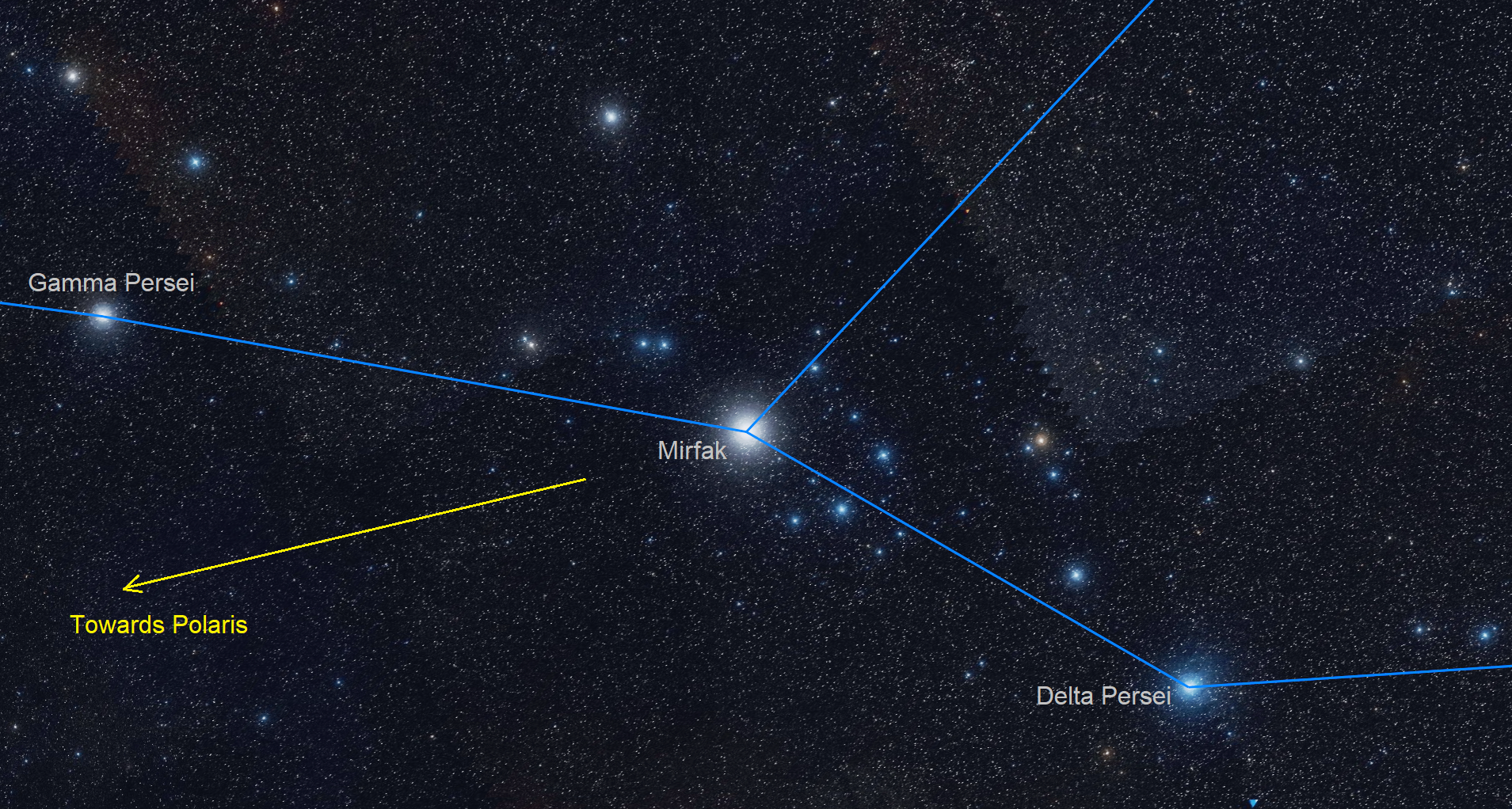

Bright stars can still be appreciated when the moon is full and bright, as it will be this week. This image from Stellarium shows the central part of the constellation Perseus, the Hero. His brightest star Mirfak, aka Alpha Persei, is at centre. Surrounding Mirfak is a large grouping of bright, young, hot stars known as the Alpha Persei Cluster, the OB Association, Melotte 20, and Collinder 39. They are easily seen in binoculars and in telescopes at low magnification. This view is zenith-up when facing northeast. Top to bottom spans 6 degrees, or a palm’s width, of sky

Happy New Year, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of December 27th, 2020 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together!

Merry Perihelion! It arrives on Saturday. In the meantime, you can observe the interesting aspects of the bright, beautiful moon when it becomes full on Tuesday – sadly, to the detriment of the Quadrantids Meteor Shower. Don’t neglect still-close-together Jupiter and Saturn after sunset, Mars in middle-night, and bright Venus before dawn. And watch Medusa’s eye brighten on Thursday evening. Read on for your Skylights!

Earth Closest to the Sun

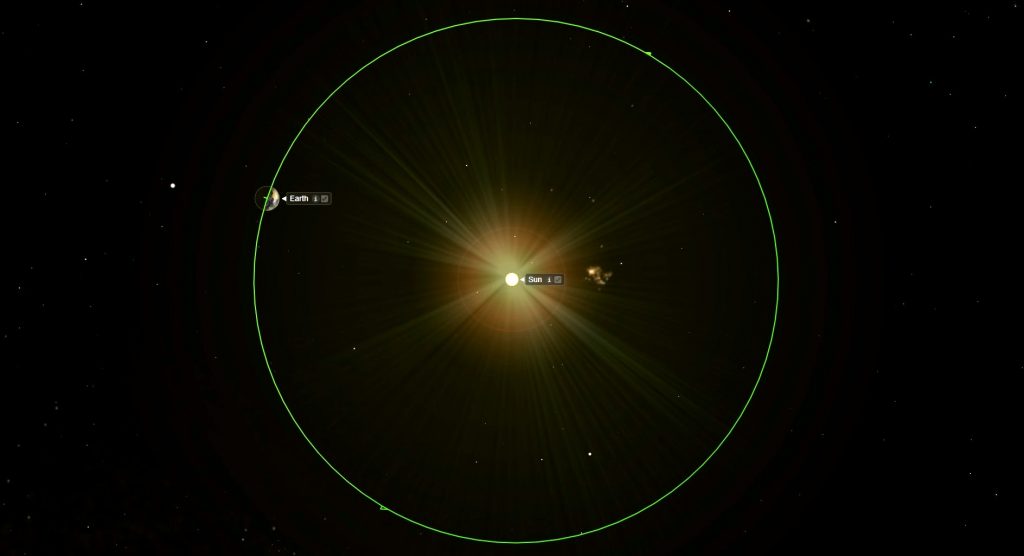

Merry Perihelion! On Saturday morning, January 2 at 14:00 Greenwich Mean Time, or 9 am EST, the Earth will be at perihelion, its minimum distance from the sun for the year. At that time Earth will sit 147.093 million km from our star – or 1.67% closer than our mean distance of 1.0 Astronomical Units. Earth’s distance from the sun varies throughout the year because our orbit is elliptical enough to varying the Earth-sun distance by 3.3%.

Do you feel warmer? You shouldn’t – as winter-chilled Northern Hemisphere dwellers will attest, daily temperatures on Earth are not controlled by our proximity to the sun, but by the number of hours of daylight we experience, which is only about 9 hours at this time of the year in the Great Lakes region.

See Medusa’s Pulsing Eye

Algol, also designated Beta Persei, is among the most accessible variable stars for astronomy enthusiasts. This star has been known to vary in brightness since antiquity – so the ancient Greeks decided that it represented the pulsing eye of Medusa the Gorgon, whose severed head is being held aloft by Perseus (the Hero). Algol’s visual brightness dims noticeably for about 10 hours, on a regular, predictable schedule, once every 2 days, 20 hours, and 49 minutes. This happens because a dim companion star orbiting nearly edge-on to Earth crosses in front of the much brighter main star, reducing the total light output we receive. This is known as an eclipsing binary system.

On Thursday, December 31 at 7:10 pm EST (or 0:10 GMT on January 1), Algol will reach its minimum brightness of magnitude 3.4, which is almost exactly the same as the star Rho Persei (or ρ Per) that sits two finger widths to Algol’s right. When at minimum brightness, observers in the Eastern Time zone will find Algol high in the eastern sky. Five hours later, at 12:10 am EST (or 5:10 GMT), Algol will be halfway up the western sky, and will have brightened to its usual magnitude of 2.1.

Quadrantids Meteor Shower Peak

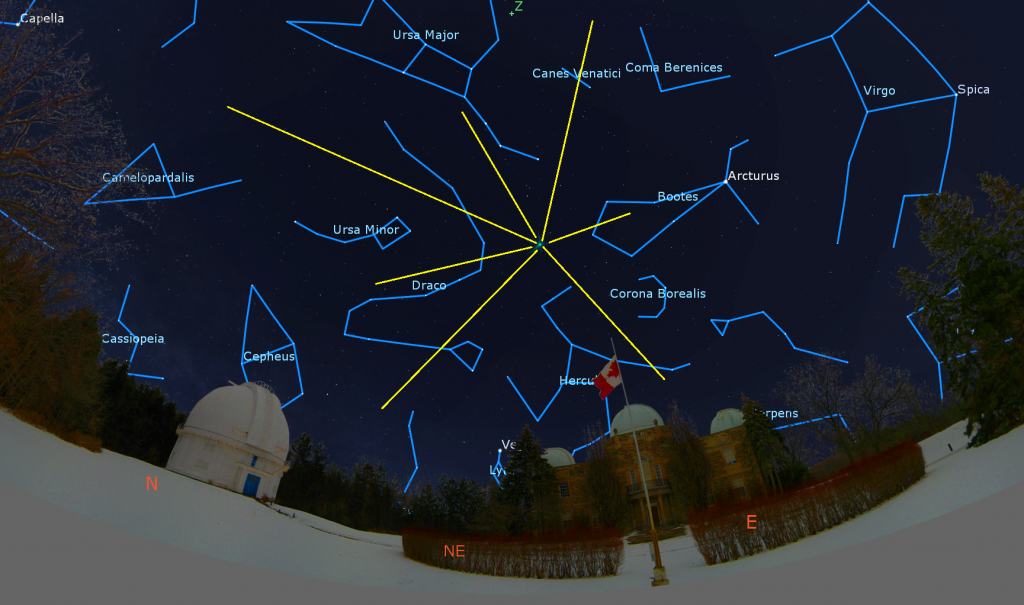

Named for a now-defunct, northerly constellation called Quadrans Muralis (the Mural Quadrant), which was located in northern Boötes (the Herdsman), the annual Quadrantids meteor shower runs from December 30 to January 12. This shower’s most intense period, when 50 to 100 meteors per hour can occur, lasts for only about 6 hours surrounding the peak, which is predicted to occur on Sunday, January 3 at 10:00 Greenwich Mean Time (or 5 am Eastern time). During those hours, the Earth will be traversing the densest part of a cloud of tiny particles in space that were deposited over time by the repeated passages of an asteroid designated 2003EH.

When the particles strike our upper atmosphere at tremendous speed, they ionize the air molecules along a 1-metre wide zone that can stretch for kilometres – producing the streaks of light we see overhead as meteors. Quadrantids commonly produce bright fireballs because the stony particles are also burning up.

The best time for viewing the shower will be before dawn, when the shower’s radiant, which lies beyond the tip of the Big Dipper’s handle, will be high in the northeastern sky. Meteor showers are usually worldwide events – but this one’s very northerly radiant will not climb above the horizon for observers in the Southern Hemisphere, reducing the numbers for them. Unfortunately, a bright moon will greatly reduce the number of Quadrantids meteors everyone sees in 2021.

To see the most meteors, find a wide-open, dark location, preferably away from light polluted skies, and just look up with your unaided eyes. The fields of view of binoculars and telescopes are too narrow to be useful for meteors. Don’t spend too much time watching the radiant because the meteors appearing near that location will be exhibit short streaks. Try not to look at your phone’s bright screen – it’ll ruin your night vision. Just keep your eyes heavenward – even while you are chatting with companions. Don’t forget to bundle up, and Happy hunting!

The Moon

The nearly full moon will shine in the afternoon sky all around the world today (Sunday). After the sun goes down, you’ll be able to see that the moon is sitting just to the lower left (or celestial east) of the bright, reddish star Aldebaran and the dimmer stars that form the sideways triangular face of Taurus (the Bull). As the night unfolds Taurus will rotate upright and the moon will move upwards. On Monday evening, the moon will be between the bull’s horn tips, which are marked by the stars Zeta Tauri on the bottom/left (celestial south) and Elnath on the top/right (celestial north).

On Tuesday night, the moon will reach its full moon phase at 10:28 pm EST (03:28 Greenwich Mean Time). The December full moon, colloquially known as the Oak Moon, Cold Moon, and Long Nights Moon, always shines in or near the stars of Gemini (the Twins). Since it’s opposite the sun on this day of the lunar month, the moon becomes fully illuminated, and rises at sunset and sets at sunrise. Full moons during the winter months at mid-northern latitudes reach as high in the midnight sky as the summer noonday sun, and cast similar shadows.

Indigenous people have their own names for the full moons, which marked time and lit the way of hunters and travelers at night before modern conveniences like flashlights. Unlike our regulated western calendar, they linked the full moon to what is happening in the environment around them. Because this moon is occurring just before the start of January, two sets of names may apply.

The Ojibwe of the Great Lakes region call the December full moon Manidoo Giizisoons, the “Little Spirit Moon”. For them it is a time of purification and of healing of all Creation. Their January moon is Gichi-Manidoo Giizis, the “Great Spirits Moon”. It is manifested through the northern lights, and is a time to honour the silence and realize one’s place within all of Great Mystery’s creatures. The Woodland Cree of the Central Canada call the December moon Thithikopiwipisim, the “Hoar Frost Moon”, when frost sticks to leaves and other things outside. Their January moon is Opawachikanasis, the “Frost Exploding Moon”, when trees crackle from cold temperatures and extreme cold weather arrives.

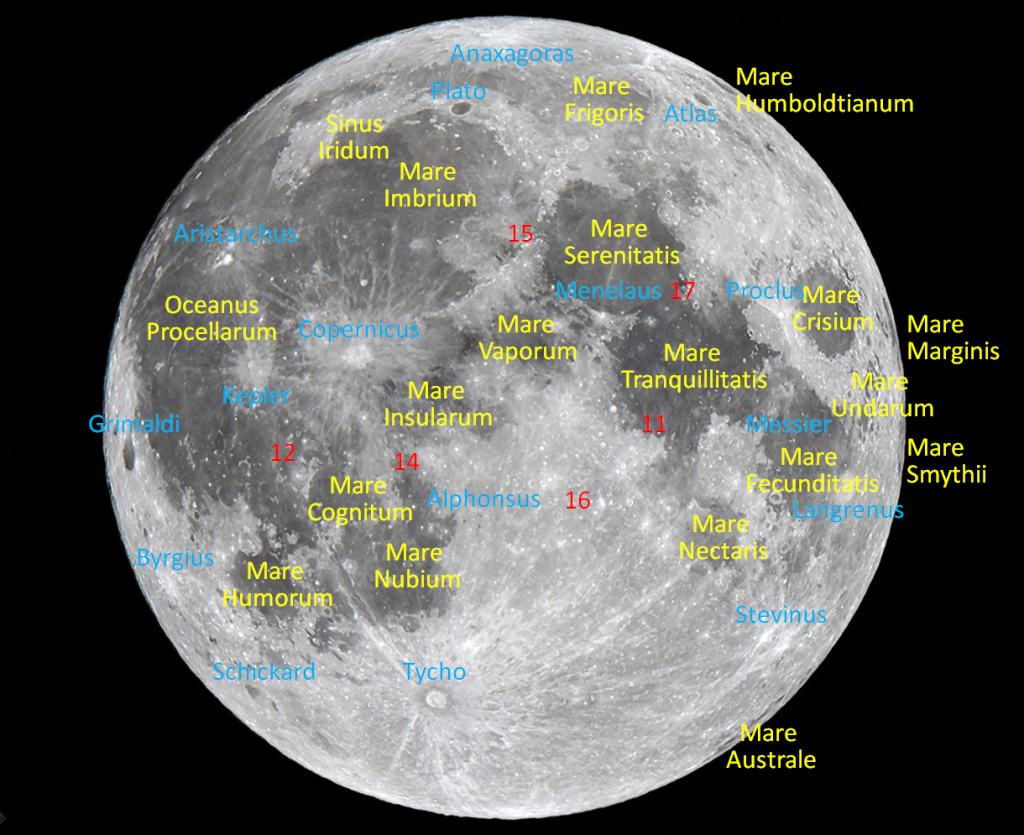

When you face a full moon, the sunlight shining on it is coming from directly behind you – the same way the projector in the rear of a cinema lights up the movie screen in front of you. That sunlight is arriving straight-on to the moon’s surface, so it doesn’t generate any shadows. Every variation in brightness and colour you see on the full moon is due entirely to the moon’s geology, not its topography! Now you can easily distinguish the dark, grey basalt rocks from the bright, white, aluminum-rich anorthosite rocks.

The basalts overlay the various lunar maria, Latin for “seas” – coined because people used to think they were water-filled. The maria are basins excavated by major impactors early in the moon’s geologic history and then later infilled with dark basaltic rock that upwelled from the interior of the moon late in the moon’s geological history.

The much older and brighter parts of the moon are composed of anorthosite rock. Those areas are higher in elevation and are heavily cratered because there is no wind and water, or plate tectonics, to erase the scars of impacts. By the way, the bright, white appearance is produced by sunlight reflecting off of the crystals the rock is made of – the same sort of crystals you see in the granite countertops in Earth’s kitchens. And yes, there are coloured rocks on the moon.

Some of the violent impacts that created the craters in the highland regions also threw bright streams of ejected material far outward and onto the darker maria. We call those streaks lunar ray systems. Some rays are thousands of km in length – like the ones emanating from the very bright crater Tycho in the moon’s southern central region.

Use your binoculars to scan around the full moon. There are smaller ray systems everywhere! There are also places where craters punched into the maria have ejected dark rays on to white rocks. And, since the dark basalt overlays the white, older rock below, you can find lots of craters where a hole has been punched through the dark rock, producing a white-bottomed crater!

Several of the maria link together to form a curving chain across the northern half of the moon’s near-side. Mare Tranquillitatis, where humanity first walked upon the moon, is the large, round mare in the centre of the chain. You can plainly see that this mare is darker and bluer than the others, due to its basalt being enrichment in the mineral titanium. That’s one of the reasons why Apollo 11 was sent to that location.

By the way, Earth-bound telescopes – even the largest ones – cannot see the items left by the astronauts on the moon. When the air is particularly steady, the smallest feature you can see on the moon with your backyard telescope is about 2 to 6 km across – far larger than a lunar module descent stage. Only the cameras on spacecraft in orbit around the moon can photograph astronauts’ footprints, lunar rover tracks, and equipment.

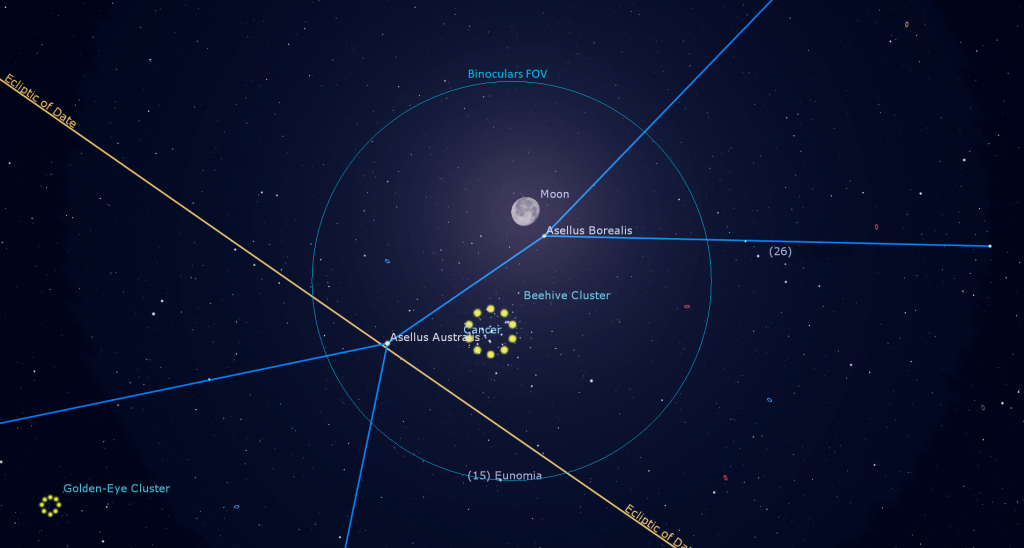

On Wednesday night, the now-waning gibbous moon will complete its trip through Gemini. When the moon rises in the eastern sky in late evening on New Year’s Eve, it will positioned several finger widths above (or 4 degrees to the celestial northwest) of the large open star cluster known as the Beehive, or Messier 44, in Cancer (the Crab). The cluster, which contains at least 1000 stars, extends for two full moon diameters across the sky. The moon and the cluster will fit together in the field of view of your binoculars. In the pre-dawn hours of New Year’s Day, the moon’s eastward orbital motion will have carried it much closer to the Beehive. Whenever you plan to view them, to best see the cluster’s stars, hide the bright moon just outside the top edge of your binoculars’ field of view.

From Friday to Sunday, the moon will pass through the stars of Leo (the Lion) – but they won’t rise in the east until late evening.

The Planets

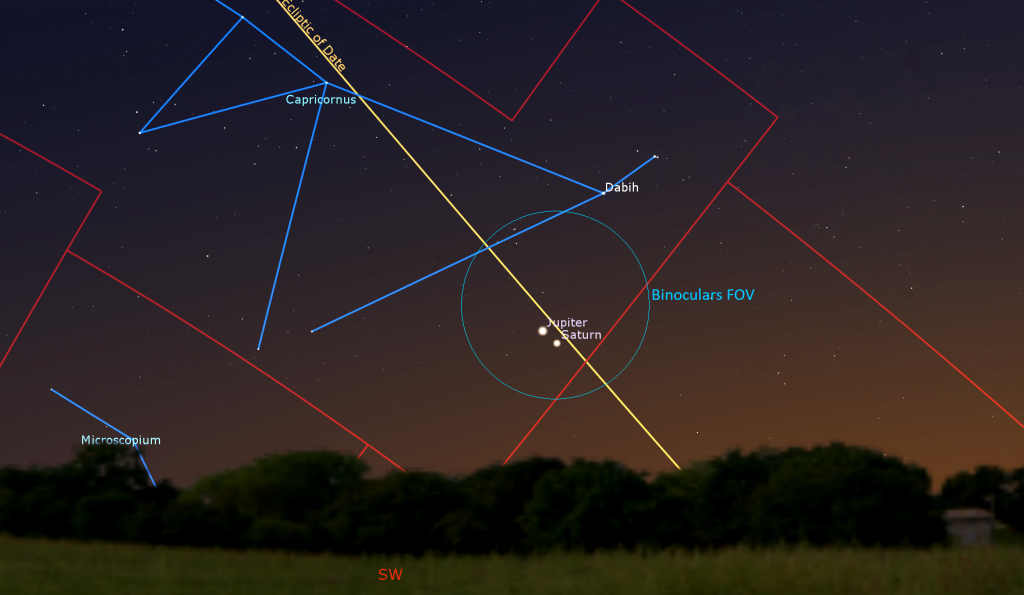

After last week’s close meeting of Jupiter and Saturn, the two planets are separating from one another – but now brighter Jupiter is on the left (east) of one-tenth as bright Saturn. They’ll remain telescope-close-together until about Tuesday. Every night, they’ll also be sinking more and more into the western twilight – so the sooner you see them, the better.

Don’t fret if you don’t have a telescope. Just head outside after sunset and look low in the southwestern sky, with your unaided eyes or binoculars, for bright Jupiter and dimmer Saturn sitting nearby. If you can’t see them, they might be hidden by a nearby building, tree, or hill. Because they are following the sun down, start looking before 5 pm local time. After 5:30 pm local time, the two planets will be less a fist’s diameter above the horizon – and descending!

Good binoculars should let you see the four large Jupiter moons that Galileo Galilei discovered in January, 1610. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, they dance around the planet from night to night – although one or more can be hidden by Jupiter at any given time. A telescope will also be able to show you Saturn’s rings, and possibly Saturn’s largest, brightest moon, Titan! (Don’t forget that your telescope might flip and/or mirror-image the scene.)

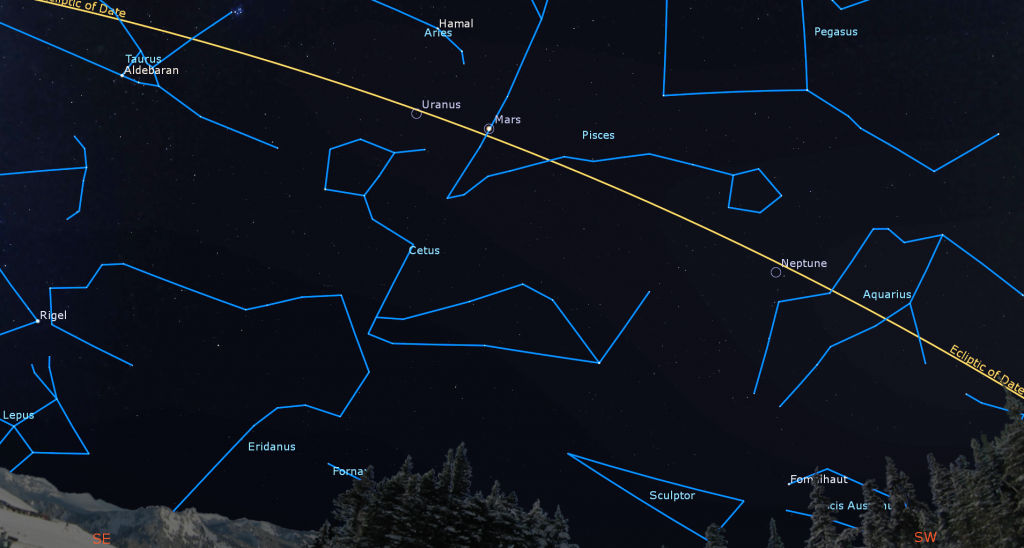

Mars is still a wonderful evening target! This week, the bright, reddish-tinted planet will already be shining high in the southeastern sky after dusk. Mars will climb to its highest point and best viewing position – more than halfway up the southern sky – at about 7:15 pm local time. The planet is moving slowly eastward across the V-shaped stars of Pisces (the Fishes). The red planet is steadily fading in brightness and size – so view it at the earliest opportunity.

Blue-green Uranus is among the stars of southern Aries (the Ram) – a fist’s diameter below and between Aries’ two brightest stars Hamal and Sheratan. For context, that region of the sky is a fist diameter to the left (or 9° to the celestial east) of Mars. At magnitude 5.7, Uranus is usually within reach of backyard telescopes, binoculars, and even sharp, unaided eyes – but not when the bright moon is in the evening sky.

Deep blue Neptune is located four fist diameters to the lower right (or 39 degrees to the celestial west) of Mars. It’s just left of the stars of northeastern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). The dim, magnitude 7.86 planet is sitting less than a finger’s width to the upper left (or 0.7 degrees to the celestial east) of the medium-bright star Phi Aquarii or φ Aqr. This week, dim and distant planet will already be in the lower part of the southern sky, and descending, after dusk. But wait for moonless skies next week to try seeing it.

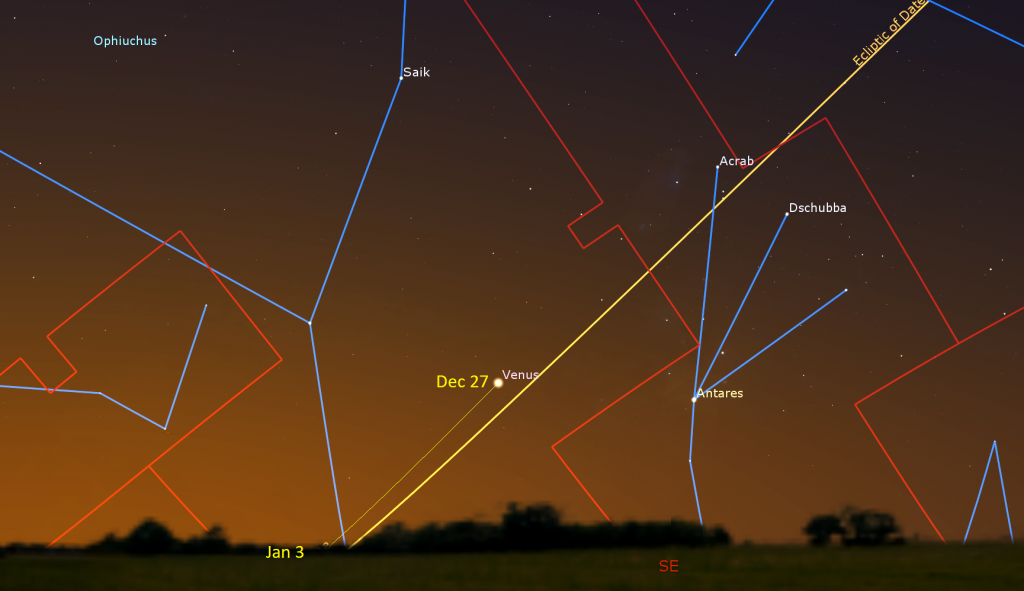

Venus has been gleaming in the eastern morning sky for some time now – but now it is sinking into the pre-dawn twilight. This week Venus will rise at about 6:20 am local time, and then remain visible in the eastern sky until sunrise while it is carried higher by the rotation of the Earth. This week, the planet will be traveling down (or celestial eastward) – across the stars of southern Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer). See if you can spot the bright, reddish star Antares sitting a palm’s width to Venus’ right.

At the end of this week, Mercury will start to become visible low in the southwestern sky after sunset.

Appreciating the Pleiades

If you missed last week’s information on the beautiful open star cluster known as The Pleiades, or the Seven Sisters, I posted it here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory is taking this week off, as is public astronomy programming from many clubs, libraries, and universities. See you next year!

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory Youtube channel, where they offer free online viewing through their rooftop telescopes, including their 1-metre telescope! Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National will return in 2021. You can find more details, and the schedule of future sessions, here and here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!