The Solstice, Lunar X, and Great Conjunction on Monday – plus Meteors, Moon Doings, and a Christmas Reindeer Rides the North Pole!

Ian Wheelband of Ashburn, Ontario captured this pre-Great Conjunction image of Jupiter and Saturn through his telescope on Friday evening, December 18, 2020. The planets will be far closer together on Monday, December 21, 2020.

Happy Solstice, Winter Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of December 20th, 2020 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together!

Wow! Monday brings the December Solstice, the Great Conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn, and a Lunar X and L-O-V-E! The moon will shine in evening skies worldwide for viewing through your binoculars and telescopes after the gas giants set post-sunset. I highlight the gorgeous Pleiades star cluster and a Reindeer rides the Pole. Read on for your Skylights!

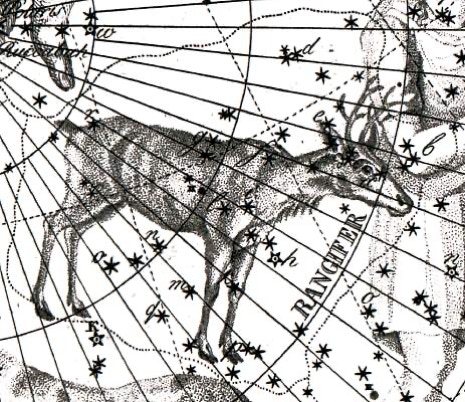

A Christmas Constellation – Rangifer (the Reindeer)!

According to Ian Ridpath, French astronomer Pierre-Charles Le Monnier (1715–99), in a star chart published in his 1743 book La Théorie des Comètes, created a faint, far-northern constellation close to the north celestial pole between Cepheus (the King) and Camelopardalis (the Giraffe). When illustrating the track of the Comet of 1742 through the north polar region of the sky, Le Monnier envisioned a reindeer on the comet’s course!

Labelled in various old charts as Rangifer and Tarandus, he connected up some of the modest, magnitude 4 and 5 stars sitting between the “W” of Cassiopeia and Polaris. You have probably not heard of this star pattern because it is not one of the IAU’s official 88 constellations. Ian’s story about the reindeer is here. I think I’ll have to look for the critter on the next clear night!

‘Tis the Seasonal Change

Happy Holidays, everyone! Or, as we astronomers say, “Have a Happy Solstice and a Merry Perihelion!”

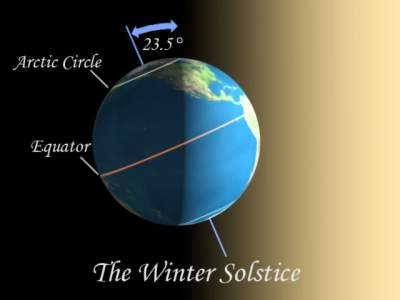

The December solstice, or winter solstice, will occur on Monday, December 21 at 5:02 am Eastern Time (or 10:02 Greenwich Mean Time). At that precise moment, the north pole of Earth’s axis of rotation will be leaning in a direction opposite from the sun. That event marks the beginning of winter for the Northern Hemisphere – but not winter weather, as I’ll discuss below. On the day of the winter solstice, the sun’s highest point in the daytime sky, which always occurs at local noon, is lower than on any other day of the year – so the sun is farthest south of the Celestial Equator. (An object’s highest position in the sky is called its culmination.)

At the December solstice, the points on the horizon where the sun rises and sets are shifted well south of east-west, so the arc that the sun traces out across the daytime sky is much shorter than on any other day of the year – and it therefore needs much less time to make that crossing. With noon still pinned at mid-day, it’s the sunrise and sunset times that are later and earlier, respectively – so Northern Hemisphere dwellers receive the shortest duration of daylight and the longest nights for the year.

The arc of the sun’s path continues to shorten if you move farther north on Earth – until you reach 66°33′48.4″ North latitude. That’s the Arctic Circle. Anywhere along that ring around the Earth, the sun won’t rise at all on the solstice – but you would still see a twilit sky around noon-time. North of about 80° N, it remains dark 24 hours a day until spring. Great for astronomy – if you can stand the cold!

The sunlight that northerners get this at time of year is weaker in intensity because it’s spread over a larger area, the same way a flashlight beam looks dimmer when you shine it obliquely at a wall (try it!). The sun weakens more and more as you travel farther from the Equator.

Fewer daylight hours and weaker sunlight result in less received solar energy (insolation) and therefore colder temperatures! It is not the case, as some people think, that days are colder in winter because we are farther from the sun (a position called aphelion). That event happens every year in early July. On the contrary – Earth’s minimum distance from the sun (perihelion) occurs every January 4, give or take a day.

After Monday, our days will slowly start to grow longer again. For our friends in the Southern Hemisphere, the sun will attain its highest noon-time culmination for the year on the December solstice, and kick off their summer season. Their winter will commence six months from now, at the June solstice.

Some scholars think that Christmas was deliberately scheduled close to the winter solstice, and Easter close to the vernal equinox, because the early non-Christian “pagans” were already holding celebrations at that time to mark the astronomical changing of the seasons.

The Moon

If you got your hands on binoculars or a telescope for seeing the conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn, keep it handy! This week, for observers all around the world, the moon will be shining in the late afternoon and evening sky. As our natural night-light increases its angle from the sun, it will be waxing fuller in phase and staying up later each night – and it will look amazing in binoculars and backyard telescopes!

The parts of the moon alongside the pole-to-pole boundary that separates its lit and dark hemispheres are receiving sunlight at a very shallow angle. It brightly illuminates every peak and crater rim, and casts deep black shadows from every raised surface. Scan your optics along the unlit side of that boundary, watch for tall, isolated mountain peaks catching the rising sun. On the lit side of the boundary look for deep craters that will have dark floors until the sun climbs higher. That terminator boundary line shifts east to west (or right to left for Northern Hemisphere observers) night after night, and even hour after hour – so check back regularly, if you have clear skies.

Tonight (Sunday) the waxing crescent moon will share the sky with Jupiter and Saturn starting immediately after sunset. The planets will set fairly early – but the moon will linger until late evening among the dim stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer).

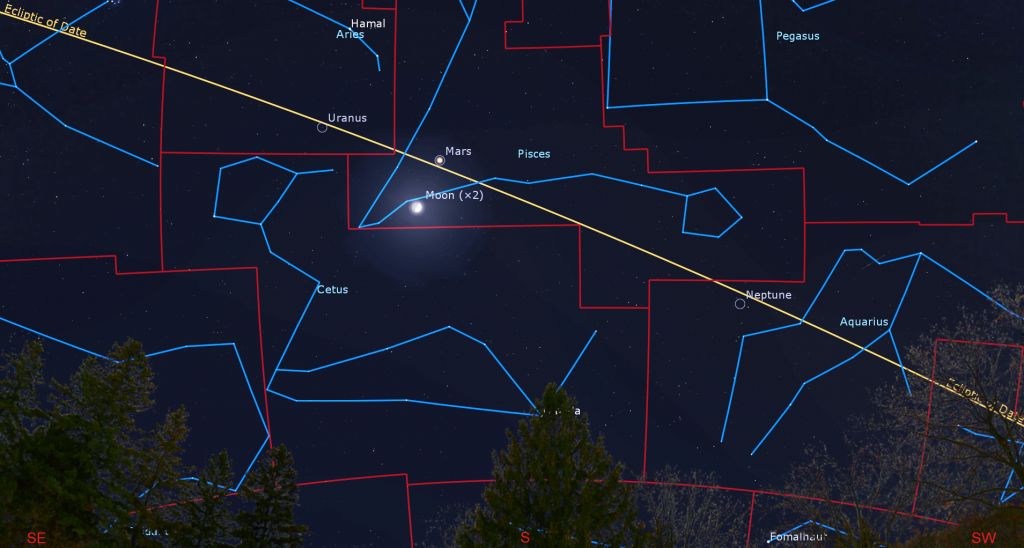

From Monday to Thursday, the moon will swim between two more water constellations. Cetus (the Whale) will be below (or to the celestial south of) the moon’s orbit, and Pisces (the Fishes) will be above that track. The moon will complete the first quarter of its orbit around Earth at 6:41 pm EST (or 23:41 Greenwich Mean Time) on Monday. At first quarter the relative positions of the Earth, sun, and moon will cause everyone on Earth to see the moon half-illuminated – on its eastern side.

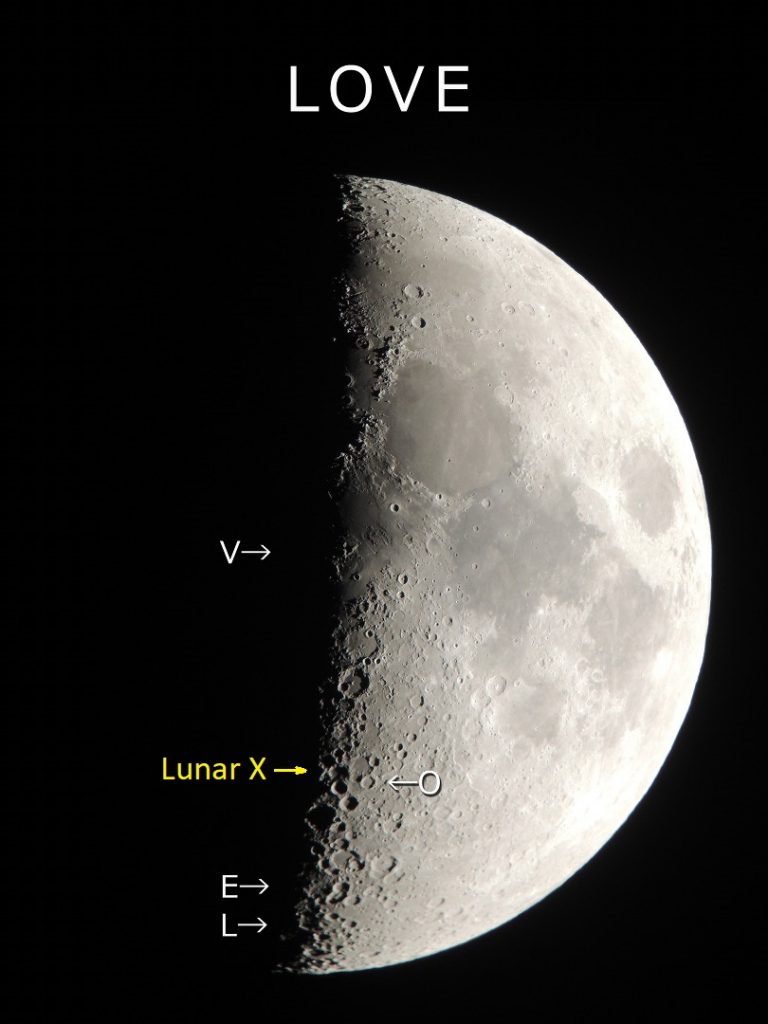

Several times a year, for a few hours near its first quarter phase, a feature on the moon called the Lunar X becomes visible in strong binoculars and backyard telescopes. This month it will occur on Monday night! When the rims of the craters Purbach, la Caille, and Blanchinus are illuminated from a particular angle of sunlight, they form a small, but very obvious X-shape. The phenomenon called is pareidolia – the tendency of the human mind to see familiar objects when looking at random patterns. The Lunar X is located near the terminator, about one third of the way up from the southern pole of the Moon (at lunar coordinates 2° East, 24° South). A prominent round crater named Werner sits to its lower right.

The X is predicted to start forming by about 11 pm EST on Monday, peak in intensity at about 1 am, and then disappear an hour later. It should be visible anywhere on Earth where the moon is shining in a dark sky during that time window, which corresponds to 4:00 to 6:00 GMT on December 22. Simply adjust for your difference from those time zones. Unfortunately, for the Great Lakes Region, the moon will be descending in the southwestern sky, and will set while the X is visible – but the moon will sit higher for observers farther west.

At the same time, you can look for the Lunar V and the Lunar L. The “V” is produced by combining the small crater Ukert with some ridges to the east and west of it. It is located a short distance above the moon’s equator at lunar coordinates 1.5° East, 8° North. For a further challenge, see if you can see the letter “L” down near the moon’s southern pole. Its position is to the southwest of three prominent and adjoining craters named Licetus, Cuvier, and Heraclitus, which resemble a Mickey Mouse’s head shape. Some people claim they can see a letter-E on the moon during the Lunar X period, too. Then, by picking a round crater along the terminator to serve as the “O”, you can spell L-O-V-E! Let me know if you see them.

On Tuesday and Wednesday, the terminator will fall just to the left (or lunar west) of Rupes Recta, also known as the Straight Wall. This feature is very obvious in good binoculars and backyard telescopes. The rupes, Latin for “cliff”, is a north-south aligned fault scarp that extends for 110 km across the southeastern part of Mare Nubium – that’s the large dark region in the lower third of the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere (under Wilma Flintstone’s chin). The Straight Wall is always prominent a day or two after first quarter, and again just before third quarter. For reference, the very bright crater Tycho is located due south of the Straight Wall.

On Wednesday night the moon (then in a waxing gibbous phase) will sit less than a palm’s width below (or 5 degrees to the celestial south of) bright, reddish Mars. By the time the duo sets in the west after midnight, the diurnal motion of the sky will lift the moon to Mars’ left. You can also try to spot Mars in binoculars during the late afternoon by using the moon below it as your guide.

Later on Wednesday night, observers in most of Canada and the continental USA can see the moon pass in front of (or occult) the medium-bright star designated Nu Piscium (or ν Psc). The exact start and end times for the event vary by location. In the greater Toronto area, the upper, dark edge of the moon will cover the star at 9:16 pm EST. Astronomers call that moment the star’s ingress. The star will emerge (egress) from the bottom, lit edge of the moon at 11:52 pm EST. The event can easily be viewed in a backyard telescope – but your telescope will likely flip and/or invert the regular, binoculars view. Since times vary a little by latitude, be sure to start watching a few minutes before ingress and egress.

Look at the Golden Handle on the moon on Friday night, when the terminator will fall to the left (or lunar west) of Sinus Iridum, the Bay of Rainbows. The circular, 249 km diameter feature is a large impact crater that was flooded by the same basalts that filled the much larger Mare Imbrium to its right (lunar east). Sinus Iridum looks like a rounded, handle-shape on the western edge of that mare. You can see it with sharp eyes – and easily in binoculars and backyard telescopes. The “Golden Handle” is produced because slanted sunlight is brightening the eastern (left-hand) side of the prominent, curved Montes Jura mountain range (the old crater rim) that surrounds the bay on the top and left (north and west). The rim extends into Mare Imbrium as a pair of protruding promontories named Heraclides and Laplace at the bottom and top, respectively. Sinus Iridum is almost craterless, but hosts a set of northeast-oriented dorsae or “wrinkle ridges” that are revealed under magnification at this phase. I posted a close-up photo of the area here.

On the coming weekend, the very bright moon will move through the stars of Taurus (the Bull), passing between the bright little Pleiades star cluster and the bull’s triangular face, with its bright, orange stars Aldebaran.

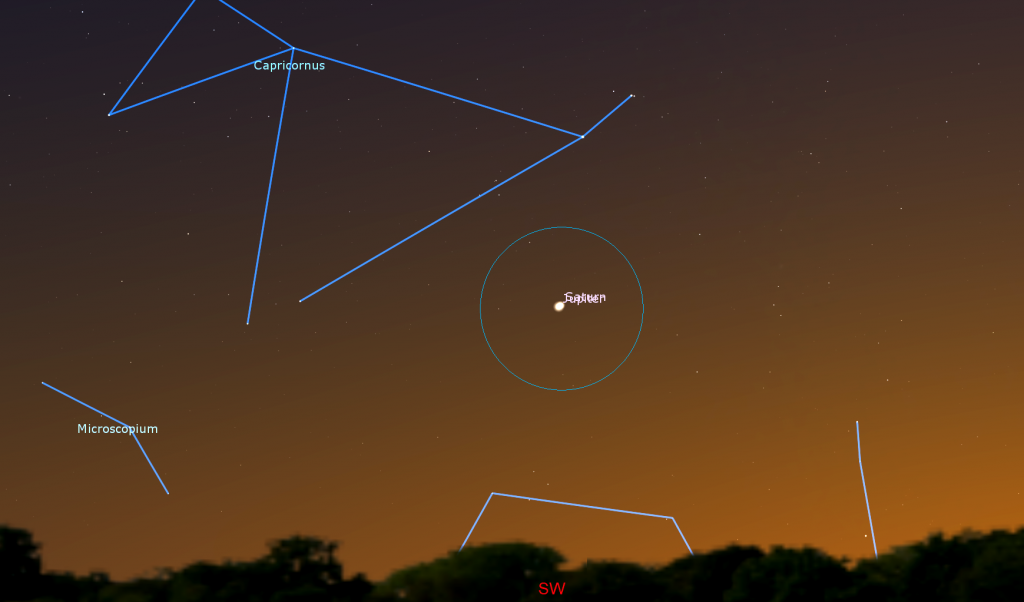

The Great Conjunction

The so-called Great Conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn will occur low in the southwestern sky after sunset on Monday, December 21. It’s a worldwide event. Those two planets move close to one another every 19.76 years, but this very close meeting will see faster Jupiter will pass only 6.25 arc-minutes below Saturn. (That’s just one-fifth of a full moon’s diameter.) To the unaided eyes, the two planets will look like a single, bright ”Solstice Star” – but not as bright as Venus alone frequently gets. Binoculars will still show Jupiter and Saturn as separate dots, but the real treat will be seeing Jupiter with its moons and Saturn with its rings sitting side-by-side in a magnified telescope view! Any size of telescope will work for that.

Good binoculars should let you see the four large Jupiter moons that Galileo Galilei discovered in January, 1610. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, they dance around the planet from night to night – although one or more can be hidden by Jupiter at any given time. Your telescope will also be able to show you Saturn’s rings, and possibly Saturn’s largest, brightest moon, Titan! (Don’t forget that your telescope might flip and/or mirror-image the scene.)

The two planets won’t be this tightly spaced again until March 15, 2080, so it’s worth making the effort to see them – and/ or snap a photo. You don’t need any special equipment. Just head outside after sunset and look low in the southwestern sky for bright Jupiter and one-tenth as bright Saturn sitting close to it. If you can’t see them, they might be blocked by a nearby building or hill. Because they are following the sun down, start looking before 5 pm local time. By 6 pm local time, the two planets will be less a fist’s diameter above the horizon – and descending!

After Monday, Jupiter will slowly start to pull away from Saturn – but they’ll remain telescope-close until about December 29, which is good news considering how cloudy December can be. Every night, they’ll also be sinking more and more into the western twilight – so the sooner you see them, the better. I wrote more about why the conjunction is happening here last week, and Blake Nancarrow and I recorded a full information video about the event on YouTube here.

For those of us with cloudy skies on Monday, RASC is partnering with Explore Scientific to bring you a star party of epic proportions! Explore Scientific will be livestreaming throughout the day on their channels (list and links available here). RASC members will be joining for the evening livestream, starting at 7:30 pm EST. There will be guest presenters from across the country.

Ursids Meteor Shower Peak

The annual Ursids meteor shower, produced by debris dropped by periodic comet 8P/Tuttle, runs from December 17 to 23. The shower will peak during the early hours of Tuesday, December 22, when seeing between 5 and 10 meteors per hour is possible under dark skies. The best time to watch will be the hours before dawn. A waxing, half-illuminated moon will have set at around midnight, leaving the sky nice and dark for seeing meteors. True Ursids will appear to radiate from a position in the sky above the Little Dipper (Ursa Minor) near Polaris, but the meteors can appear anywhere in the sky. I shared tips for viewing meteor showers here, and I streamed an Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy session about meteors and meteorites on YouTube here.

The Planets

Mars is still a wonderful evening target! This week, the bright, reddish-tinted planet will already be shining in the southeastern sky after dusk. Mars will climb to its highest point and best viewing position – more than halfway up the southern sky – at about 7:30 pm local time. Mars will set in the west during the wee hours. The planet is moving slowly eastward inside the V-shaped stars of Pisces (the Fishes). The red planet is steadily fading in brightness and size – so view it at the earliest opportunity.

Blue-green Uranus is among the stars of southern Aries (the Ram) – a fist’s diameter below and between Aries’ two brightest stars Hamal and Sheratan. For context, that region of the sky is a fist diameter to the left (or 13° to the celestial east) of Mars. At magnitude 5.7, Uranus is usually within reach of backyard telescopes, binoculars, and even sharp, unaided eyes – but not when the bright moon is in the evening sky.

Deep blue Neptune is located more than three fist diameters to the lower right (or 36 degrees to the celestial west) of Mars – to the left of the stars of northeastern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). The dim, magnitude 7.86 planet is sitting less than a finger’s width to the upper left (or 0.7 degrees to the celestial east) of the medium-bright star Phi Aquarii or φ Aqr. This week, dim and distant planet will already be in the lower part of the southern sky, and descending, after dusk.

Venus has been gleaming in the eastern pre-dawn sky for some time now – but it will leave us in the coming weeks when it sinks into the pre-dawn twilight. This week Venus will rise at about 6 am local time, and then remain visible in the eastern sky until sunrise while it is carried higher by the rotation of the Earth. This week, the planet will be traveling down (or celestial eastward) – out of the stars of Scorpius (the Scorpion) and into southern Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer).

Appreciating the Pleiades

The beautiful open star cluster known as The Pleiades, or the Seven Sisters, which sits about one and a half fist widths above (or 13 ° to the celestial northwest of) the bull’s face, is one of my favorite wintertime objects. It’s also designated Messier 45 (or M45), part of Charles Messier’s famous list of comet-like objects.

The Pleiades is made up of the young, hot blue stars named Asterope (“A-STER-oh-pee”), Merope, Electra, Maia, Taygeta, Celaeno, and Alcyone. And those stars are indeed related – born of the same primordial gas cloud. In Greek mythology, they were the daughters of Atlas, and half-sisters of the Hyades. Only six of the sister stars are usually seen with unaided eyes – their parent stars Atlas and Pleione are huddled together at the east end of the grouping.

Galileo was among the first to observe the cluster in a telescope. In 1610, he published a sketch made at the eyepiece. The Pleiades cluster is located about 450 light years away from the sun, and it makes a wonderful target in binoculars or a telescope at low magnification, where many more siblings are revealed! A large telescope under dark skies will also reveal blue nebulosity around the stars – reflected light from unrelated gas and dust that the stars are passing through. This proper motion will eventually carry the cluster to a position below Orion’s feet!

Not surprisingly, many cultures, including Aztec, Maori, Sioux, Hindu, and more, have noted this object and developed stories around it. Many indigenous groups view the Pleiades as the doorway in to the afterlife, or the portal through which humans first fell to Earth – naming it the Hole in the Sky. In Japan, it is called Suburu, and forms the logo of the eponymous car maker. Due to its similar shape and diminutive size, some people mistake the Pleiades for the Little Dipper.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory Youtube channel, where they offer free online viewing through their rooftop telescopes, including their new 1-metre telescope! Details are here.

On Monday evening, December 21 from 4 to 6 pm, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory will broadcast live views of the conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn on their YouTube channel here.

For those of us with cloudy skies for the Jupiter-Saturn conjunction on Monday, RASC is partnering with Explore Scientific to bring you a star party of epic proportions! Explore Scientific will be livestreaming throughout the day on their channels (list and links available here). RASC members will be joining for the evening livestream, starting at 7:30 pm EST. There will be guest presenters from across the country.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National will return in 2021. You can find more details, and the schedule of future sessions, here and here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!

2 Responses

Thank you for such a wonderful explanation about the December solstice / Winter solstice. We heard about the term before but reading your article and through your graphics, especially about the arc of the sun across the sky, we finally understood it better. Looking forward to the longest night and the shortest day turning to the shortest night and the longest day in six months!

Hello, Vikas! What a nice note to receive after sending out my Skylights late yesterday. I did indeed spend a bit more time on wording the solstice explanation – so it’s gratifying to know it was understood and appreciated. Please extend greetings from Sue and I to your family, and have a wonderful, peaceful, and safe Holiday period. And let’s hope for a hole in the clouds tonight! Regards, Chris