Northern Autumn Arrives, the Evening Moon Clips the Scorpion’s Claw and Jumps Past Jupiter, and Venus Veers by Vesta!

This image of the young crescent moon by Dylan O’Donnell shows Earthshine – sunlight reflected off of Earth that slightly illuminates the dark portion of the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere. Watch for it early this week. NASA APOD for March 20, 2015.

Hello, Autumn Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of September 20th, 2020 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together!

The moon will be perfectly placed for evening viewing this week around the world – and it will visit Jupiter and Saturn. Those two bright planets – and still-brightening Mars – will beg for views in the evening sky. Gleaming Venus will slide past asteroid Vesta in the east before dawn, where you can also see the zodiacal light – if your skies are dark enough. Here are your Skylights!

Happy Northern Autumnal Equinox!

At 9:31 am Eastern Daylight Time on Tuesday, September 22, the September equinox will occur – kicking off autumn in the Northern Hemisphere. Here’s why…

As the Earth travels around the sun (completing one orbit every year), the sun moves continuously eastward through the fixed and distant background stars. The circular path it traces around the sky is called the ecliptic, and it repeats every year. (Because Earth’s orbit is close to the orbital planes of all the other planets, major Solar System bodies are always found near the ecliptic.)

The Earth’s axis of rotation is tilted 23.5° away from the ecliptic – so an imaginary circle painted on the sky directly overhead of our equator runs through a different group of stars. In fact, that celestial equator divides the celestial sphere into two great bowls, the Northern Hemisphere stars and the Southern Hemisphere stars. Since the Earth’s equator is due south for those of us located in the Northern Hemisphere, the celestial equator is always in the southern part of our sky, and it runs from the eastern horizon to the western horizon.

You can think of the equator and ecliptic circles as two hula hoops with the same centre – us. One hoop is tilted by 23.5° – so that the two circles only touch at two spots in the sky, one in western Virgo (the Maiden) and the other in western Pisces (the Fishes). The sun reaches those spots during the third weeks of March and September, respectively. Another way of thinking about it is that half of the ecliptic runs through stars in the southern celestial hemisphere, and the other half runs through northern stars – so the sun spends half of the year among the northern stars and the other half among the southern stars.

At the moment of an equinox, the sun is crossing one of the hula intersection points – as if it is “stepping over” the equator. The full disk of the sun takes about 13 hours to cross the equator – but we define the equinox as the precise time when the centre of the sun slides across. This year that will occur at 9:31 am EDT, or 13:31 Greenwich Mean Time. The equinoxes and solstices are global events. Just add or subtract the appropriate number of hours to determine when northern autumn will begin for your own time zone.

On the September, or autumnal, equinox the sun is passing into the southern bowl of the sky. Six months later, on the vernal equinox, it will cross the celestial equator at the other intersection point – this time venturing into the northern bowl of the sky. At that moment, Spring will begin for the Northern Hemisphere. (I like to avoid using the seasonal terms “vernal” and “autumnal” because our seasons are reversed for people living in the Southern Hemisphere.) The solstices occur mid-way between the equinoxes – in June and December.

An equinox triggers several interesting effects. At either equinox, the sun rises due east and sets due west. For the six months following the September equinox, the sun will spend all of each day among the Southern Hemisphere stars, and climb high in the sky for the lucky folks who live there! The higher sun will take more daylight hours to cross the sky and will deliver more highly-concentrated solar radiation, producing warmer weather. (Compare the intensity of a flashlight’s light when it’s beamed straight at a wall versus obliquely at the wall. The bright circle of light gets weaker when it’s spread into an oval.) During the same months, North Americans, Europeans, and Asians have to accept shorter, colder days and longer nights (which are great for warmly dressed astronomers). On the day of the equinox, everyone worldwide experiences 12 hours each of day-time and night-time. This is where the term equinox, Latin for “equal night”, comes from.

The nights around the equinoxes offer a higher likelihood of aurorae at high northern and southern latitudes. Just as two bar magnets lined up with their poles in the same direction repel one another strongly, the Earth’s magnetic field repels the sun’s field. At the equinoxes, the Earth’s axis tilts partly sideways compared to the sun, so the two “magnets” aren’t lined up as well, reducing Earth’s ability to deflect the sun’s field and the charged particles that trigger aurorae in our upper atmosphere.

At this time in September every year, the Earth is travelling almost directly towards the stars that mark the upraised club of Orion (the Hunter) and the toes of Gemini (the Twins). That produces the “bugs on a windshield” effect when the Orionids meteor shower particles strike the Earth’s upper atmosphere and produce the streaks of light we see. (At the same time, Earth is travelling almost directly away from the stars of Sagittarius (the Archer) and Ophiuchus (the Water-Bearer).)

A final aside: The sun’s journey along the ecliptic produced the Zodiac. Early sky watchers noted that, in the course of one year, the sun passed through the same twelve (well, thirteen actually) constellations – avoiding all others. Those “special constellations” became the zodiac. It also crossed through the same zodiac constellation every year on the same range of dates – leading to the astrology that many follow to this day. At that time, the equinoxes were called the First Point of Aries and the First Point of Libra – because those constellations hosted the sun in March and September several thousand years ago. Over the centuries, the wobble of the Earth’s axis (precession) has caused the two equinox points to shift one zodiac constellation to the west.

Zodiacal Light

For about half an hour before dawn during the moonless periods in September and October every year, the steep morning ecliptic favors the appearance of the zodiacal light in the eastern sky, for observers in mid-northern latitudes. Zodiacal light is sunlight scattered by interplanetary particles concentrated in the plane of the solar system. It is best seen in areas free of urban light pollution.

Between now and the next full moon (on October 1), look just above the eastern horizon for a broad wedge of faint light centred on the ecliptic, which runs through Venus and the bright star Regulus in Leo (the Lion). Don’t confuse the zodiacal light with the Milky Way, which is positioned further to the southeast. I posted a nice picture of it here.

The Moon

This will be a fantastic week to enjoy views of the moon all around the world. Our beautiful natural satellite will be filling up with light each night as it swings east – increasing its angle with the sun. Practicing on the moon is the best way to learn how to aim and focus your telescope, and to see how the different eyepieces work.

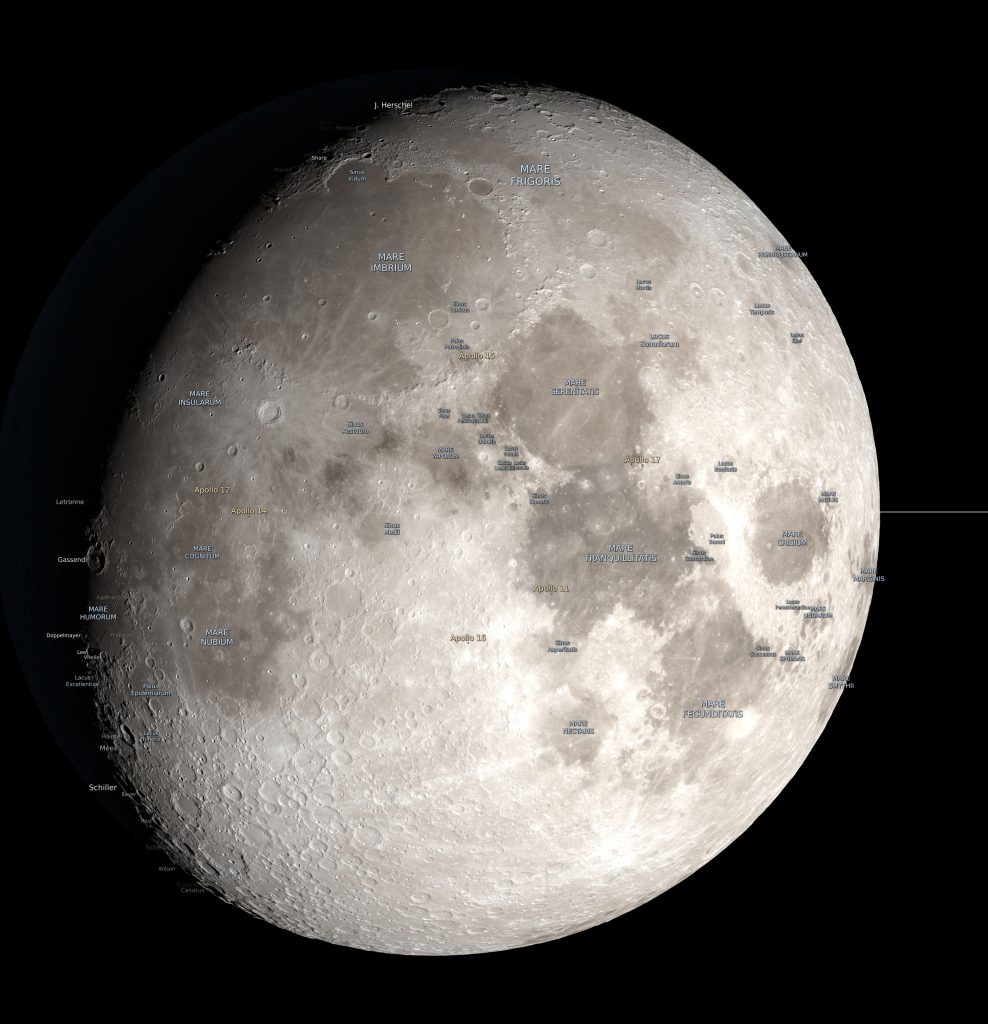

The curved, pole-to-pole terminator is the boundary that divides the moon’s lit and dark hemispheres. It shows where the sun is rising on the moon. The near-horizontal sunlight arriving there bathes peaks and crater rims in bright light and casts long shadows west of them. Every little bump is enhanced – and with no atmosphere to scatter light, the contrast is dramatic. Even better – new regions are highlighted each night, or even hour-by-hour. The nearly-horizontal sunlight shining on the terrain near the terminator looks especially exciting under magnification. Choose a prominent, deep crater on the lit side, near the terminator. One night, it will have a dark, empty floor – the next, a central peak might catch the sun’s rays. And a few nights later, everything inside it will become fully illuminated. It’s fun! You can reproduce the effect at home using bowls or pots and a flashlight in a dark room. I’ll post an annotated moon diagram here.

The moon will shine as a lovely crescent in the southwestern sky after sunset tonight (Sunday) and tomorrow. Watch for Earthshine – sunlight reflected off Earth that slightly illuminates the dark part of the moon’s Earth-facing disk.

Two interesting stars from Libra (the Scales) will be near the moon on Sunday night. Zubenelgenubi will sit two finger widths below the moon, and Zubeneschamali will be a palm’s width above the moon. Long ago, those two stars made up the extended claws of Scorpius (the Scorpion)! Use binoculars or your telescope on Zubenelgenubi to split it into two close-together stars – one much brighter than its mate.

On Monday evening, the moon will pass visit the three modern-day claw stars of Scorpius. Those stars, named Acrab, Dschubba, and Fang, form an upright chain – from top to bottom. As the moon gets ready to set in the west it will approach Acrab and eventually cross in front of (or occult) it. In the GTA, the leading dark edge of the moon will cover Acrab at about 9:48 Eastern Daylight Time. The star will re-appear on the bright, opposite side of the moon at about 10:45 pm EDT. Observers living well west of Ontario will be able to see the entire event.

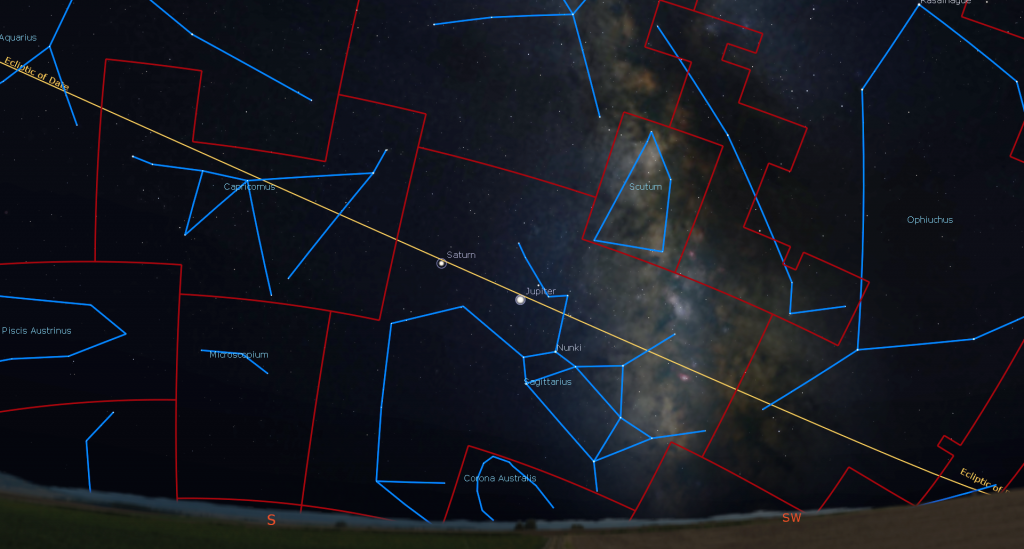

The moon will complete the first quarter of its orbit around Earth at 9:55 pm EDT on Wednesday (or 1:55 GMT on Thursday). At that phase, the relative positions of the Earth, sun, and moon will cause us to see a half-illuminated moon – on its eastern side. At first quarter, the moon always rises around noon and sets around midnight, so it is also visible in the afternoon daytime sky. On Wednesday evening, the moon will be situated just to the upper right (or celestial northwest) of the teapot-shaped stars of Sagittarius (the Archer).

On Thursday night, the now gibbous moon will begin its monthly visit with the gas giant planets Jupiter and Saturn. As the evening sky darkens, the bright planet Jupiter will become visible several finger widths to the upper left (or 4.5 degrees to the celestial northeast of) the moon in the southern sky. The moon and Jupiter will fit together into the field of view of binoculars. By the time they set soon after midnight local time, the moon will slide east, closer to Jupiter – and the diurnal rotation of the sky will raise Jupiter above the moon.

After 24 hours of eastward motion, the bright waxing moon will sit several finger widths to the lower left (or 3.6 degrees to the celestial south of) yellowish Saturn in the southern sky after dusk on Friday. By the time the moon and Saturn set shortly before 1 am local time, the moon will be farther from Saturn – and to the planet’s left. These moon-Jupiter-Saturn conjunctions will make beautiful wide field photographs when composed with some interesting foreground scenery.

On the coming weekend, the bright moon will pass through the relatively dim stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). On Sunday night, September 27, the moon’s terminator will fall just left (or lunar west) of Sinus Iridum, the Bay of Rainbows. The circular, 249 km diameter feature is a large impact crater that was flooded by the same basalts that filled the much larger Mare Imbrium to its right (lunar east) – forming a rounded, handle-shape on the western edge of that mare. You can see it easily with sharp eyes and binoculars. A “Golden Handle” effect is produced by the way slanted sunlight brightly illuminates the eastern side of the prominent Montes Jura mountain range that surrounds the bay on the top and left (north and west), and by a pair of protruding promontories named Heraclides and Laplace to the bottom and top, respectively. Sinus Iridum is almost craterless, but hosts a set of northeast-oriented dorsae or “wrinkle ridges” that are revealed in a telescope at this phase.

The Planets

Speedy little Mercury will continue to tease us in the post-sunset sky this week – but the low angle of the evening ecliptic will keep it very close to the horizon for everyone living at mid-northern latitudes. Low in the west-southwestern sky after sunset on Monday, Mercury’s rapid orbital motion will bring it very close to Virgo’s brightest star, Spica. Look for brighter Mercury sitting just 40 arc-minutes (about 1.3 times the diameter of a full moon) to Spica’s right (celestial west), allowing both object to fit into the field of view of a backyard telescope at medium magnification. On Tuesday evening, Mercury will climb to sit a similar distance above Spica. Observers viewing from southerly latitudes will be able to see the duo more easily.

Venus, the other inner planet, has been gleaming in the eastern pre-dawn sky for some time now. It will rise at about 3:25 am local time this week, and then remain visible until sunrise as it is carried higher in the eastern sky by the rotation of the Earth. Viewed in a backyard telescope, Venus will show a gibbous, half-illuminated shape. This week, the planet will depart the modest stars of Cancer (the Crab) and descend into Leo (the Lion).

In the eastern pre-dawn sky on the mornings surrounding Tuesday, September 22, very bright Venus will overtake and pass the dim and slower-moving main belt asteroid Vesta. Venus will be dropping sunward faster than Vesta, so the asteroid will seem to climb in the opposite direction. At closest approach on Tuesday morning, Venus will be positioned two finger widths to the right (or 2 degrees to the celestial south) of Vesta. Magnitude -4.14 Venus will outshine magnitude 8.16 Vesta by more than 8300 times! To see how both objects move compared to the stars around them, try to view the event by 6 am local time on several mornings, as that’s when the sky will start to brighten.

Venus is shifting towards the sun – but the later sunrises at this time of year will let it shine in a dark, pre-dawn sky until early December! And while you’re up early, enjoy a view of the extremely bright star Sirius, and Orion (the Hunter) sitting well off to Venus’ upper right.

As soon as the sky starts to darken after sunset this week, very bright, white Jupiter will pop into view in the lower part of the southern sky. A while after that, dimmer, yellowish Saturn will appear, too – sitting a generous palm’s width to Jupiter’s left (east). Our window of opportunity to view those two planets is starting to close. They are getting low in the southwestern sky after 11 pm.

Good binoculars will reveal Jupiter’s four large Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto as they dance around the planet from night to night. Even a modest-sized telescope will show Jupiter’s brown equatorial belts and the famous Great Red Spot (or GRS, for short) – if the air is steady. Due to Jupiter’s 10-hour period of rotation, the GRS appears every second or third night from any given location on Earth. In the Eastern Time zone, the Great Red Spot will be crossing the planet’s disk after dusk tonight (Sunday), Tuesday, Friday, and next Sunday.

From time to time, the round, black shadows cast onto Jupiter by its Galilean moons are visible in amateur telescopes as they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk for a few hours. From 10:42 pm EDT until Jupiter sets on Tuesday evening, Io’s shadow will be traveling across Jupiter. Ganymede’s larger shadow will do the same from 10:33 pm until Jupiter-set on Saturday evening.

Saturn is a spectacular sight in any backyard telescope. Even a small one will show Saturn’s rings. From our vantage point here on Earth, they’ll be narrowing every year – until they vanish for a few weeks during the spring of 2025. Unfortunately, that event will happen while Saturn is close to the sun – so we’ll have to settle for seeing them as a very thin line. In a telescope, the rings are almost as almost as wide as Jupiter’s disk. See if you can see the Cassini Division. It’s the narrow, dark gap that separates Saturn’s main inner ring from its outer one.

A small telescope will also show several of Saturn’s moons – especially its largest, brightest moon, Titan! Because Saturn’s axis of rotation is tipped about 27° from vertical (a bit more than Earth’s axis), we are seeing the top surface of its rings – and its moons can arrange themselves above, below, or to either side of the planet. During evening this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the left of Saturn tonight (Sunday) to the right of the planet next Sunday. (Remember that your telescope might flip the view around.)

Reddish Mars will continue to increase in disk size and brightness until Earth is closest to Mars on October 6. Try to see Mars’ lighter and darker patches, and its bright, little southern polar cap, in your telescope. This week, the Red Planet will be rising in the east soon after 8 pm in your local time zone. Then it will cross the sky until dawn, when it will be positioned about four fist diameters above the western horizon. Nothing in the southern nighttime sky is as bright and red! Mars is moving retrograde now, causing the planet to appear to travel backwards compared to the stars beyond it. This week, Mars will be within the narrow “V” of modest stars at the bottom of the constellation of Pisces (the Fishes). Check it out!

This week’s moon-filled sky will be less than ideal for looking for the Ice Giant planets. Blue-green Uranus will rise among the stars of southern Aries (the Ram) at about 8:30 pm local time and will sit a generous fist’s diameter to the lower left (or 13° to the celestial east) of much brighter Mars.

Neptune is located among the stars of northeastern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), about two degrees to the left (or celestial east) of the medium-bright star Phi Aquarii (or (φ) Aqr). This week, Neptune will already be in the lower southeastern sky after dusk. Then it will climb higher until about 12:30 am local time, when you’ll get your clearest view of it while it’s halfway up the southern sky.

A Tour of Cygnus the Swan

If you missed last week’s in-depth tour of Cygnus (the Swan), I posted it with photos and sky charts here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

On Monday evening, September 21 from 7 to 10 pm EDT, Ingenium – Canada’s Museums of Science and Innovation / Institute of Indigenous Research and Studies and University of Ottawa will host a free online Indigenous Star Knowledge Symposium. Details and registration are here.

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory Youtube channel, where they offer free online viewing through their rooftop telescopes, including their new 1-metre telescope! Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National will return on Tuesday, September 22, when we’ll cover telescopes for beginners – how to set them up and use them most effectively. Details and the schedule are here. In the meantime, join Jenna and John Reid on alternate Thursdays at 3:30 pm EDT as they run through the RASC’s Explore the Universe certificate.

From 8 to 10 pm on the first clear weeknight this week, members of the RASC Toronto Centre are partnering with Pickering Public Library for a free online observing session called Shoot the Moon. They’ll share views of the moon through telescopes, and share interesting info about our celestial neighbour. Register for the zoom session here.

The Canadian organization Discover the Universe is offering astronomy broadcasts via their website here, and their YouTube channel here.

On many evenings, the University of Toronto’s Dunlap Institute is delivering live broadcasts. The streams can be watched live, or later on their YouTube channel here.

The Perimeter Institute in Waterloo, Ontario has a library of videos from their past public lectures. Their Lectures on Demand page is here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!