Northern Summer Starts, Moon Joins Jupiter in Daytime, Venus Visits the Seven Sisters who Mark Maori New Year, and Hercules’ Highs!

This terrific image by Amir H. Abolfath shows a deep exposure of the sky surrounding the bright reddish star Antares, the heart of Scorpius, which shines over the southern horizon on late June evenings. Antares is within the bright orange region at lower left. To its right is the enormous globular star cluster Messier 4. The blue regions are reflection nebulae around the star Rho Ophiuchi (left of centre) and Jabbah (at upper right). Pink areas show hydrogen gas emissions. Dark opaque dust adds to the drama. NASA APOD for Oct. 14, 2020.

Hello, Solstice Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of June 19th, 2022 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

Tuesday’s solstice will trigger summer for the Northern Hemisphere, and the pre-dawn appearance of the Pleiades will start the New Year for New Zealanders. The waning moon will journey past all five bright planets in the eastern morning sky – as well as the faint asteroid Vesta and the two ice giant planets. I update two evening comets that are available for telescope owners, and highlight the best aspects of mighty Hercules. Read on for your Skylights!

The June Solstice starts the Northern Summer

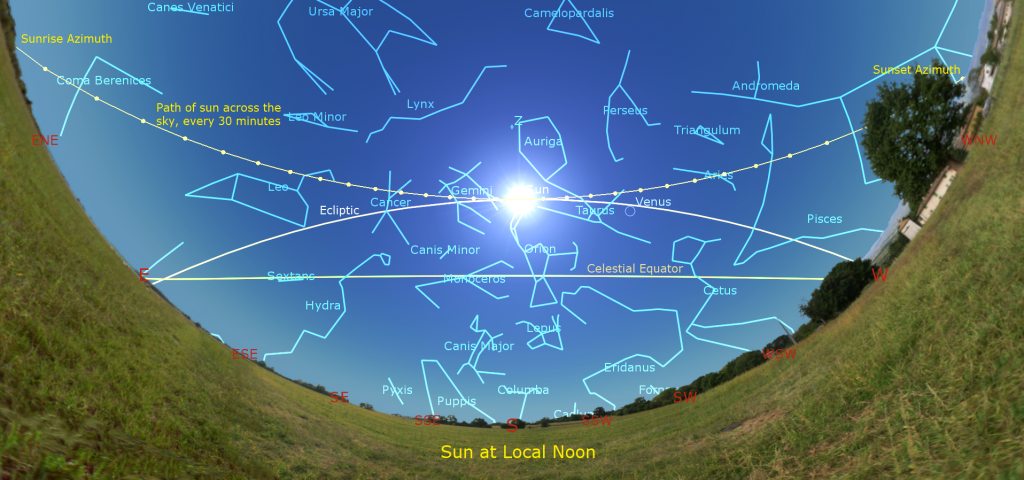

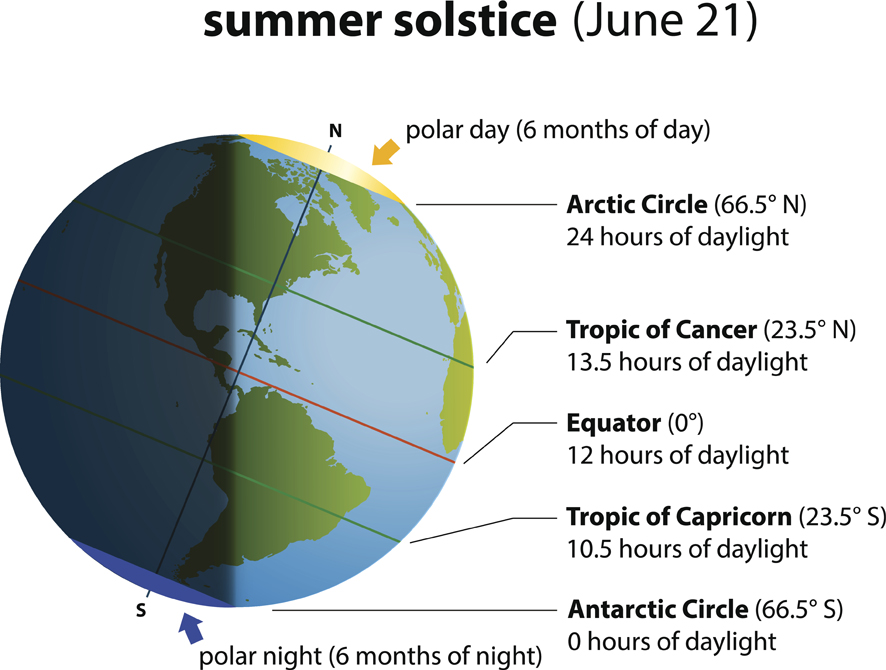

The beginning of summer for the Northern Hemisphere, known as the June Solstice or Summer Solstice, will occur on Tuesday, June 21 at 5:14 am Eastern Daylight Time (or 2:14 am PDT and 09:14 Greenwich Mean Time). At that moment, the northern end of Earth’s axis of rotation will be tipped by its maximum angle of 23.5° towards the sun. Astronomically, the sun will reach its greatest northern declination and its greatest angle from the celestial equator.

The observation that the sun was ceasing to vary in declination (its north-south component of motion compared to the fixed stars) on that date is reflected in the name solstice, which arises from the Latin expression sol sistere, ”the sun is standing still”.

For Northern Hemisphere dwellers, the sun will climb to its highest mid-day position in the sky for the year. At local noon, you shadow will be shorter than at any other time of the year. The place on Earth where the sun will be shining directly overhead at local noon is called the subsolar point. As the Earth completes a full rotation in 24 hours, the subsolar points form a ring at latitude 23.44° known as the Tropic of Cancer. The December solstice places the sun above the Tropic of Capricorn. In antiquity, when the phrase was coined, the sun resided in those two constellations on the solstices. The slow wobble of the Earth’s axis of rotation shifts the celestial positions of the sun at the solstices and equinoxes, and varies the precise latitude of the two tropics.

The sun will take the longest to cross the daytime sky – maximizing the amount of daytime hours (15 hours and 26.5 minutes for Toronto) and minimizing the night-time hours, making stargazers sad. (At the December solstice, Toronto will have only 8 hours and 55.7 minutes of daytime.)

The points on the horizon where the sun rises and sets will also reach their most northerly azimuths on Tuesday, too. At the latitude of Toronto, the sunset position at the June and December solstices varies by 67 degrees! That’s why different windows in your house favourably catch the sunset at different times of the year.

Just as the beam of a flashlight is strongest when shining directly towards a wall, and weaker when held obliquely, the higher sun’s light is more intense (more watts per square metre, to be technical). More hours of more concentrated sunlight translates to more solar energy delivered and warmer days! It is NOT the case, as some people think, that we are warmer in summertime because we are closer to the sun. That event, called perihelion, actually happens in early January every year! Moreover, the Earth is now only two weeks away from reaching its greatest distance from the sun, or aphelion, for this year, which will occur on July 4.

For our friends in the Southern Hemisphere, this solstice signals the sun’s lowest noon-time height for the year, and marks the start of their winter. The June solstice is eagerly awaited by Northern Hemisphere astronomers because, after Tuesday, the nights will lengthen!

The Moon

This will be the best week of the lunar month for evening stargazing. Earth’s natural night-light will be venturing sunward – shining in the dark pre-dawn hours and then lingering into morning daylight like an echo of the night.

On Monday morning, the barely gibbous waning moon (59%-illuminated) will rise around 1:30 am local time among the stars of eastern Aquarius (the Water-Bearer). Grab your binoculars and seek out the widely spaced trio of 4th magnitude stars named Psi1,2,3 Aquarii, which will sit two finger widths to the moon’s upper right (or 2.5° to the celestial west). They, and several more similar stars near them, form the water being poured by the bearer.

Early risers on Monday should also notice that the moon will be posing below and between very bright Jupiter (on its left, or celestial northeast) and medium-bright Saturn (to the upper right, or west). On Monday night at 11:11 pm EDT or 8:11 pm PDT the moon will officially reach its third quarter phase. (That translates to 03:11 Greenwich Mean Time on Tuesday, June 21.) By then, the moon will look half-illuminated, on its western, sunward side, but only folks viewing it near western Africa and Europe will be seeing it in that form.

The moon’s tour of the morning planets will continue with a nice photo opportunity on Tuesday morning, when its waning crescent will shine a palm’s width to the lower right (or 5° to the celestial southwest) of Jupiter in the lower part of the east-southeastern sky among the stars of Pisces (the Fishes). Jupiter will remain visible to the unaided eye from the time they rise (after 1:30 a.m. local time) until almost sunrise. Since the moon will remain visible in the morning daytime sky, you can use it to spot Jupiter in daylight through binoculars by positioning the moon towards the bottom of your field of view. Once you see Jupiter, try finding Jupiter’s bright pinpoint without the binoculars!

On Wednesday morning, low in the eastern sky before dawn, the moon’s pretty crescent will take up position a palm’s width to the right (or 5.5° to the celestial southwest) of Mars’ reddish dot. Bright Jupiter will shine off to their upper right (or celestial west). By the time the sky begins to brighten, the moon and Mars will be cosy enough to share the view in binoculars. Observers in the Southern Ocean region can see the moon cross in front of (or occult) Mars around 18:00 GMT.

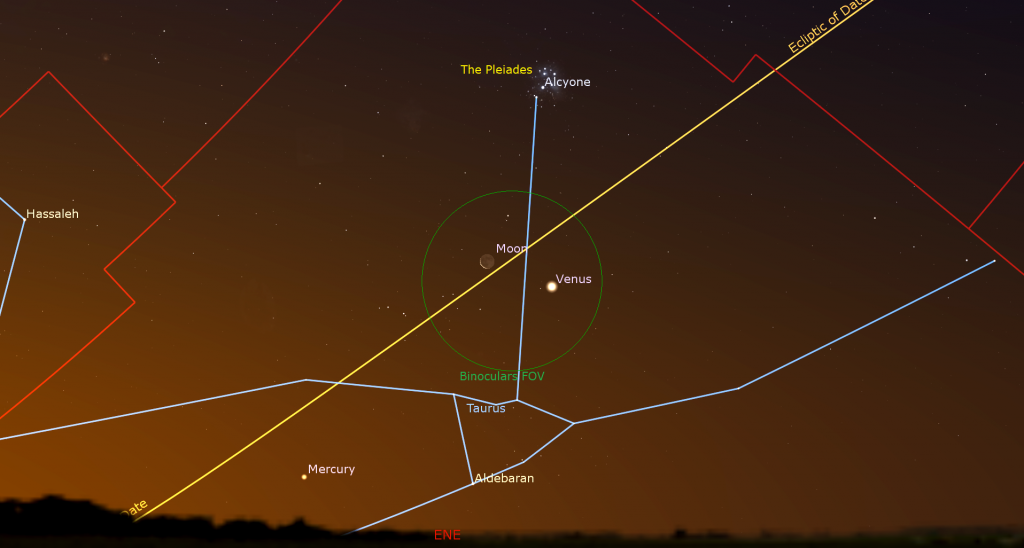

From Thursday to Saturday, the crescent moon will slide through Aries (the Ram), hopping past Uranus on the way. A gorgeous photo opportunity arrives in the hour before sunrise on Sunday, June 26 when the delicate, slim crescent of the old moon will shine just to the upper left (or 2.5° to the celestial north) of the extremely bright planet Venus. Look for the duo shining just above the east-northeastern horizon, flanked below and above by Mercury and the Pleiades star cluster, respectively. Or, just enjoy the spectacle with your unaided eyes or in binoculars. Around the world at the latitude of Toronto, try to catch them by about 4:45 am local time. Lucky observers at southerly latitudes will see the grouping in a darker sky.

The Planets

Those five bright planets will continue to shine in the eastern pre-dawn sky this week, arranged in their order from the sun – and the pretty crescent moon will offer delightful photo opportunities each morning as it passes amongst them.

Medium-bright, yellowish Saturn will sit at one end of the lengthy chain. It will officially enter the evening sky this week because it will start rising before midnight local time for mid-northern latitude observers. By sunrise, it will be in the southern sky. None of the stars of eastern Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) that surround Saturn are bright enough to confuse you. Any size of telescope will show you Saturn’s globe both above and below its rings, and up to a handful of its moons arrayed all around the planet. Since Saturn is now moving slowly westward in a retrograde loop that will last until late October, you can watch it slowly move above Capricornus’ easterly tail stars Deneb Algedi and Nashira over the coming weeks.

Mercury will rise over the east-northeastern horizon at about 4:30 am local time – anchoring the chain of planets. But Mercury’s position well below (or celestial south of) the sloping morning ecliptic will prevent observers at mid-northern latitudes from seeing the speedy planet very easily. If you want to make the attempt, try to catch it before 5 am. Even though Mercury will be swinging back toward the sun for the rest of June, its motion in the sky will be more right-to-left than downwards – extending our viewing time for the planet alignment.

Extremely bright Venus will rise over the east-northeastern horizon at about 3:45 am local time. Mercury will be positioned about 1.3 fist diameters to Venus’ lower right, giving you a nice reference point. Venus will exhibit a nearly-round shape when viewed in a telescope or in good binoculars. From Wednesday to Friday, Venus will pass a palm’s width to the lower right (or 6° to the celestial south) of the bright Pleiades star cluster – almost cosy enough to share the view in binoculars. If you view the Pleiades in twilight, you’ll be able to see only its brighter stars – the ones that suggest its other name “the Seven Sisters”. And don’t forget to catch the crescent moon near them on Sunday, June 26!

The rest of the planets will be strung out between Venus and Saturn – more or less along that ecliptic line – and there will be more of them than meets the unaided eye! The main belt asteroid (4) Vesta will be traveling a generous fist’s width to the lower left (or about 11° to the celestial east) of Saturn. To see its magnitude 6.7 speck you’ll need to hunt for it with good binoculars or a backyard telescope before the sky brightens.

By 2 am local time, the very bright, white planet Jupiter will gleam above the eastern treetops, to the lower left (east) of Saturn. Jupiter will be bright enough to remain visible until almost sunrise. The planet’s large globe, 11 times wider than Earth, will be flanked by its row of four Galilean moons. In a telescope, the planet will sport dark bands running parallel to its equator, the Great Red Spot on Tuesday, Friday, and next Sunday morning, and the small back shadow of Io crossing Jupiter on Wednesday morning. The faint, blue planet Neptune will be close to the line connecting Jupiter and Saturn, a generous fist’s diameter to Jupiter’s right.

Mars will clear the eastern horizon around 2 am local time, appearing as a medium-bright, reddish dot shining 1.3 fist widths to Jupiter’s lower right. Mars’ distance from Jupiter will increase a little every morning. In a telescope, Mars will show a tiny, 86%-illuminated disk. The red planet will brighten very slowly and grow larger as Earth’s faster orbit draws us closer to it over the coming months. Uranus is next in line, midway between Venus and Mars, but its magnitude 5.85, blue-green dot won’t be easily visible until month’s end, when it will be higher in the sky before twilight begins.

That line of planets will last for the rest of June. Turn all optics away from the east before sunrise, please!

It’s Matariki!

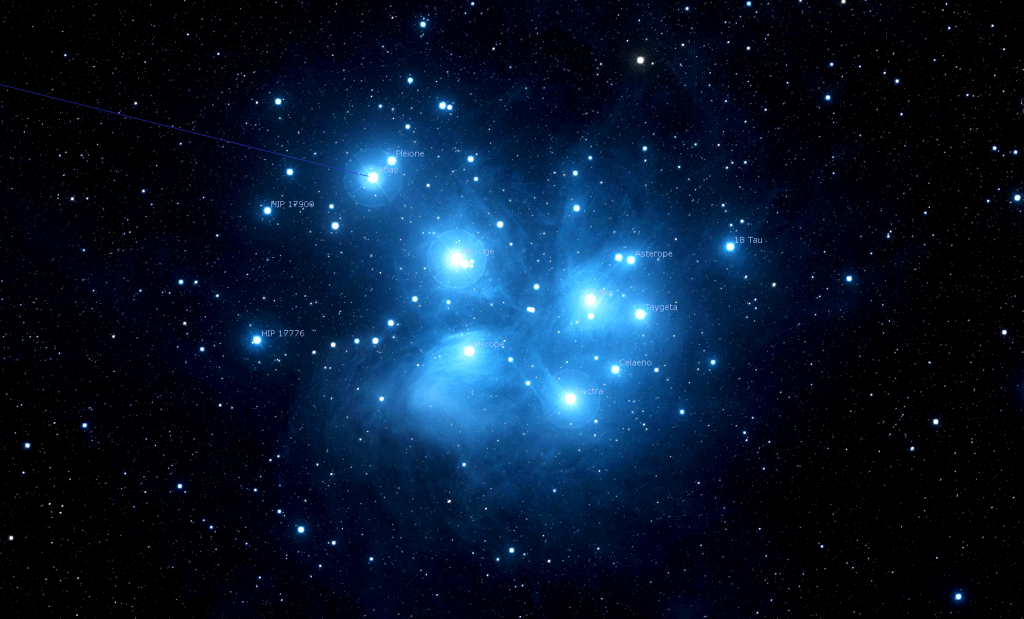

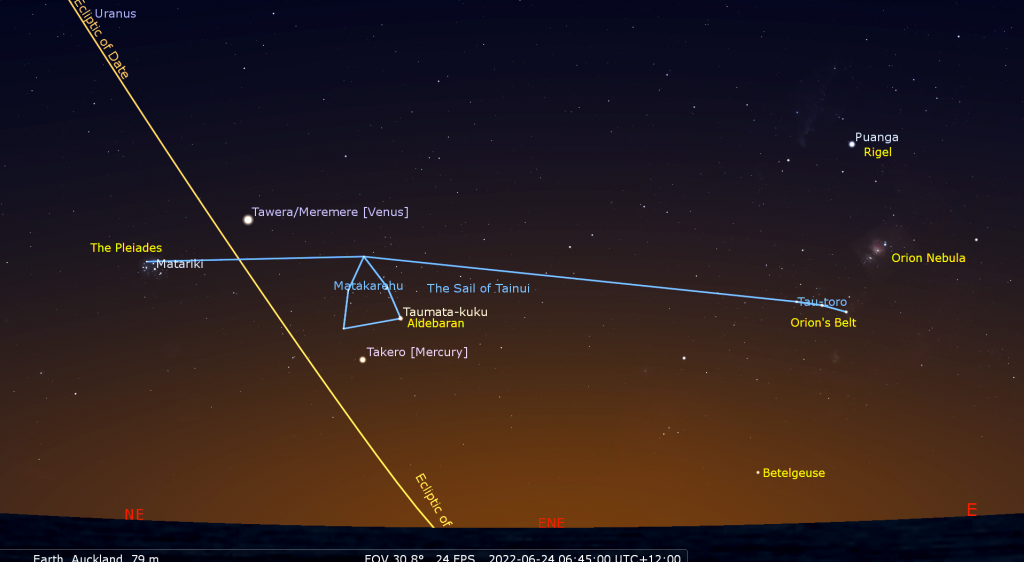

Matariki is the Māori name for the Pleiades star cluster in Taurus (the Bull). They call that constellation Matakarehu “the Sail of Tainui”. At this time of year, Taurus rises long enough before sunrise for the cluster to become visible above the eastern horizon after several months of absence from the sky. Matariki’s return during their month of Pipiri (June/July) marks the beginning of the Māori new year. Some groups opt to use the return of the bright star Puanga, better known as Rigel in Orion (the Hunter), instead.

Commencing in 2022, Matariki will become a national holiday in New Zealand – all because of indigenous astronomy! This year, Matariki will begin on Friday, June 24, the last Friday before the new moon next Wednesday. The holiday will always begin on a Friday, but the week will move in accordance with the Maori lunar calendar. For 2022, Matariki’s stars will share the sky with Venus (Tawera) and Mercury (Takero).

The word Matariki is an abbreviation of Ngā Mata o te Ariki, “Eyes of God” – referring to Tāwhirimātea, the god of the wind and weather. In the Maori story of creation, Tāne Mahuta, the god of the forest, separated his parents Ranginui and Papatūānuku. His upset brother Tāwhirimātea tore out his eyes, crushed them into pieces, and threw them into the sky as stars.

Traditionally, Maori communities, or iwi, would gather together at night during a time of the constellation’s prominence, making use of the period between harvests to celebrate and make offerings for a bountiful future.

Traditions hold that the visual appearance of the Pleiades cluster was said to predict the success of the season ahead. Clear, bright stars are a good omen, and hazy stars predict that the rest of winter (during July-August) will be cold and harsh. The brightness of each individual star predicts the fortunes of a specific thing that star represents, such as the wind, or food that grows in trees.

Exploring Hercules

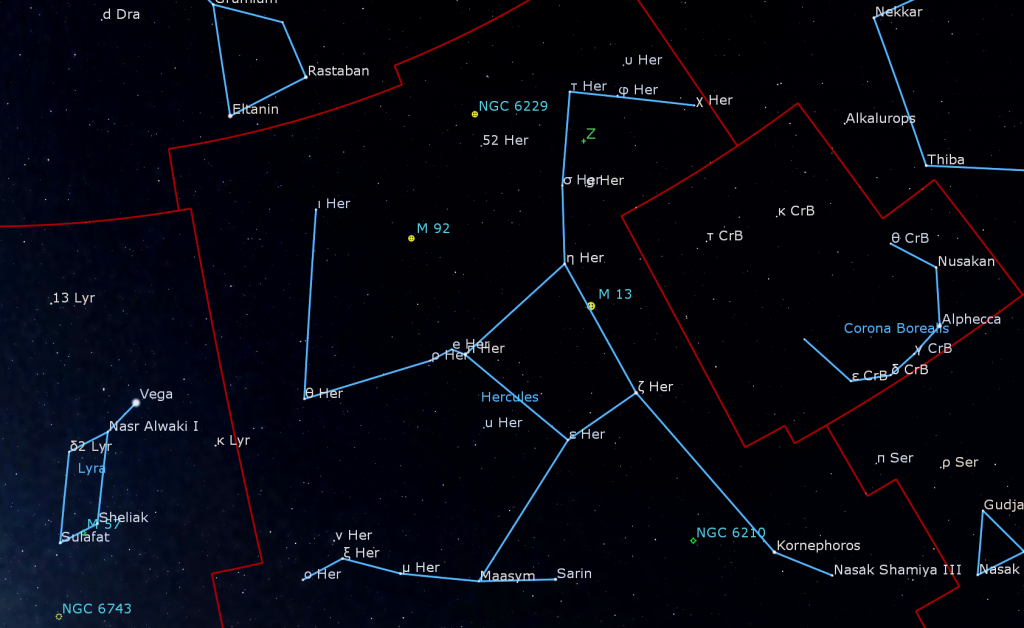

The moon will be out of the evening sky worldwide for the next two weeks, produce excellent conditions for viewing the sky’s best sights. On the next clear evening, head outside after dusk and point your finger directly overhead. That’s the zenith. While objects occupy that position, they always appear at their best because you are looking through the least amount of intervening air. The stars near the zenith barely twinkle for that reason. During late evening in late-June every year, the constellations of Boötes (the Herdsman), Corona Borealis (the Northern Crown), and Hercules sit high in the southern sky, just below the zenith. I’ll post a sky chart here. Let’s focus on Hercules, which contains one of the summer season’s best objects!

Hercules isn’t formed by bright stars, but you can still find it very easily, even from mildly light-polluted skies. Face east-southeast and look for a very bright, white star sitting about halfway up the sky. That’s Vega, the brightest star in Lyra (the Harp). Another prominent star, orange-tinted Arcturus, shines in the southern sky and higher than Vega. Between these two stellar signposts is the realm of mighty Hercules.

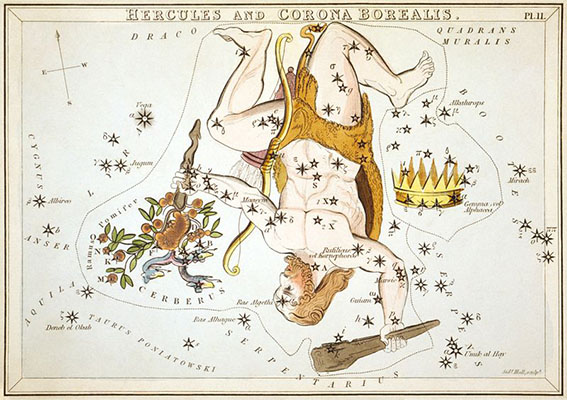

Hercules’ body is defined by a very distinctive keystone-shaped quartet of modestly bright stars. The keystone is about 6° across (a palm’s width), with its wide end toward celestial north (towards your left) and its narrow end pointed southwards (towards the lower right). The hero of mythology is upside down for Northern Hemisphere observers. His sharply bent legs extend upwards to the left (celestial north), and his two arms are outstretched downward (celestial south). The star that marks his eastern hand, named Maasym, or Lambda Herculis (λ Her), is below the keystone. It combines with four other stars to form a loose chain of five stars running left-right, each separated by a couple of finger widths. In classical drawings of Hercules he is grasping the three-headed dog Cerberus, which he was tasked with capturing as one of his twelve labours.

Hercules is the fifth largest constellation by area, and was one of the original 48 constellations tabulated in the Almagest, an early astronomy book produced in ancient Greece by Ptolemy. The early Greeks depicted Hercules, with his legs bent – as “The Kneeler” praying to his father Zeus to aid him in an upcoming battle. Beyond his feet, to our upper left, are the stars of Draco (the Dragon), ready to be crushed under his feet. To the upper right (or celestial west) of Hercules is the little circlet of stars that form the distinctive constellation of Corona Borealis (the Northern Crown).

Hercules’ location 30 degrees north of the celestial equator has allowed its stars to be seen everywhere on Earth except the southern tip of South America and Antarctica. Other cultures have formed patterns with the same stars. The indigenous Lokono or Arawak people of northern coastal South America call these stars Katarokoya (the Spirit of the Green Sea Turtle). The Ojibwe of North America used some of Hercules’ stars to form Noondeshin Bemaadizid (the Exhausted Bather) next to Madoodiswan (the Sweat Lodge), from the stars of Corona Borealis.

Let’s tour Hercules. Starting in the keystone, the right-most and brightest star is designated Zeta Herculis (or ζ Her for short). This is a binary star system situated about 35 light-years away from us, where the pair of stars orbit around one another. Both stars are yellow sun-like stars, although the brighter star is more massive and luminous. Moving clockwise and downwards, we arrive at the dimmer white star Epsilon Herculis (ε Her). Next, at lower left, is Pi Herculis (π Her). It’s a giant, orange-tinted, cool star situated about ten times farther away than Zeta. At the upper left corner of the keystone sits Eta Herculis (η Her). It is a yellowish, sun-like star, about ten times the diameter of the sun, but a bit cooler than our sun.

Hercules contains quite a few double and binary stars within reach of a backyard telescope. One of the nicest ones is modest Rasalgethi, or Ras Algethi “Head of the Kneeler”, which sits about 1.6 fist diameters to the lower right (or 16° to the celestial southwest) of Epsilon Herculis. A medium-bright star named Rasalhague sits a slim palm’s width below Rasalgethi. In a small telescope, Rasalgethi easily splits into a lovely pair of orange and greenish stars. The slightly brighter one is a red giant class star that varies in brightness randomly over months to years. The partner is a yellow sun-like star that is itself a binary star too tightly spaced to resolve. The stars are about 360 light-years away and are orbiting one another with a period of 3,600 years. This double star, like many others, was given a single name centuries before telescopes revealed that there was more than one star there.

The brightest star in Hercules, Kornephoros “Club-bearer”, sits a fist’s diameter to the lower right of the keystone, where Hercules’ elbow would be. Only about two finger widths to the lower right (or 3° to the southwest) of Kornephoros is the double star Gamma Herculis (γ Her). This is another pair that easily splits into two yellow stars in a modest telescope. But this double is a line-of-sight double star. The fainter star is actually much closer to us! Marsic or Marfik, which means “the Elbow” even though it’s at the end of his arm, is another “line of sight” double star that’s easy in a small telescope. Look for it about four finger widths to the right of Gamma.

Hercules contains one of my favorite objects, a globular cluster known as the Great Hercules Cluster or Messier 13 (or M13). This object is a tightly packed ball of at least 300,000 old stars. At magnitude 5.9, it is visible with unaided eyes under dark skies as a faint smudge, but reveals much more under magnification! It is located along the western (upper) edge of the keystone, about one-third of the way from the wide end. Your binoculars should pick it up. Midway between Hercules’ knees there is another, smaller globular cluster called Messier 92. This one is also readily visible in binoculars. A third, fainter globular cluster designated NGC 6229 sits 6.5°, or a palm’s diameter, to the lower right of M92.

Globular clusters are one of the most interesting classes of objects for stargazers. These spherical concentrations of old, densely packed stars orbit in the region just outside our Milky Way galaxy, and we’ve observed many of them around other galaxies, such as the Andromeda Galaxy. Viewed in a telescope under dark skies, they will look like a pile of salt poured onto black velvet – with a dense white center surrounded by a sprinkling of outlying stars. Each cluster looks different, varying in the scattering of stars. Photographs reveal that these objects contain a mixture of reddish, blue, and yellow stars in different proportions.

The Great Hercules Globular Cluster was first observed by British astronomer Edmund Halley in 1714 and later included as number thirteen in Charles Messier’s famous list of “not-a-comet” objects. At 21,500 light-years away, it is a relatively close member of that class of objects. It shines with a relatively bright magnitude of 5.8, and it actually covers an area of sky spanning 20 arc-minutes (or two thirds of the moon’s diameter)!

More than 150 of these clusters have been mapped around our galaxy. They are so densely packed that the stars in their interiors are extremely close together, stirring the imagination of those contemplating extraterrestrial intelligent life. Advanced civilizations on planets around stars embedded deep inside a globular cluster would be able to exchange radio messages on timescales of weeks or months – and travel between adjacent solar systems would not require the decades or centuries we would need to visit our nearest neighbours. In fact, M13 was also one of the first targets for potential contact with other civilizations, when a radio message was beamed there from the Arecibo Radio Observatory in 1974.

The stars of Hercules are host to at least fifteen known exoplanets, including one named TrES-4. At 1.7 times the mass of Jupiter, it’s one of the most massive exoplanets yet discovered. However, its calculated density is extremely low, about the same as cork! This is one of the hot-Jupiter class of exoplanets, with a surface temperature in excess of 2,000 C.

Let me know how your exploration of Hercules goes.

Faint Comet Update

Last week I wrote about two comets that are currently observable in backyard telescopes in the evening sky, especially if you view them in non-light-polluted skies. In smaller telescopes, comets resemble fuzzy grey stars. In larger telescopes, you might see a hint of green colour and a faint tail pointed away from the sun.

The brighter of the two comets, named C/2017 K2 (PanSTARRS), is travelling left to right (or celestial southwestward) through northeastern Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer). Look for it about one-third of the way up the southeastern evening sky, near the bright star Cebalrai. The comet is visible all night long, but it will be most easily seen while it is highest in the sky during the wee hours. It is currently around magnitude 9.4 and still brightening. To start this week, the comet will be located a thumb’s width to the left (or 1.5° to the celestial northeast) of Cebalrai and just below the southern edge of the open star cluster named the Summer Beehive Cluster (or IC 4665). By the coming weekend the comet will have slid two finger widths to the right of Cebalrai.

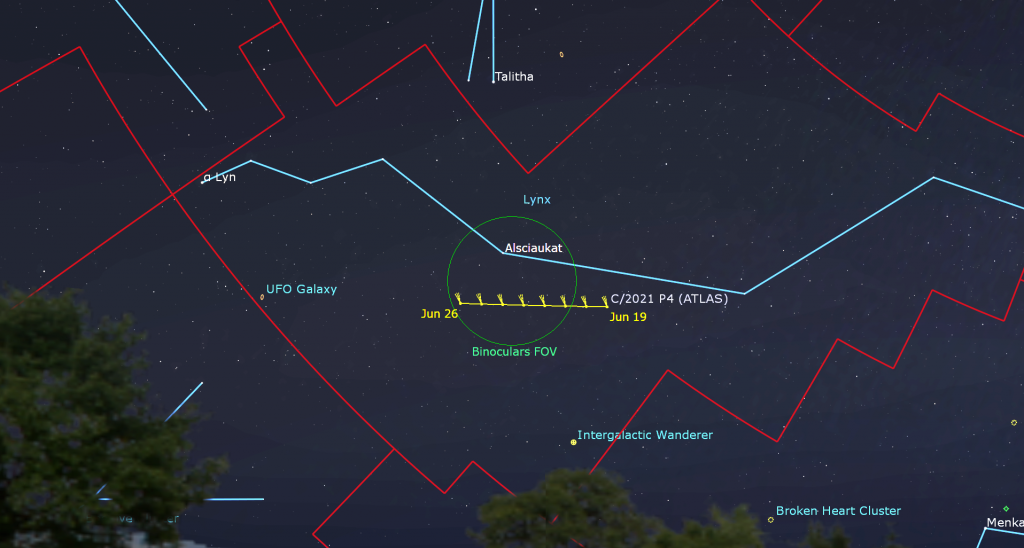

The fainter, more challenging comet named C/2021 P4 (ATLAS) is travelling right to left (or celestial southeastward) below the constellation of Lynx, which reclines low in the northwestern sky until about 1 am local time. This one is currently at a faint magnitude 10.5 and brightening. Try to view it as soon as the sky darkens fully, when it will be located three fist diameters directly below the Big Dipper’s bowl. There aren’t really any “landmarks” to help you find it, but it will be travelling generally below the medium-bright star named Alsciaukat this week. It will fly just above NGC 2683 (the UFO Galaxy) on July 5.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, July 5 at 3:30 pm EDT, when we’ll celebrate Canadians in the Stars and a summer planet preview! Plus, we’ll continue with our Messier Objects observing certificate program and share some galaxy-viewing tips. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Space Station Flyovers

The ISS (or International Space Station) will not be visible gliding silently over the GTA this week.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!