The Full Strawberry Supermoon Sports Dark Spots and Rays, A Comet Update, and Maximum Mercury in the Predawn Planet Parade!

A triangle of dark ash deposits left by long-extinct volcanoes are easily visible in the crater Alphonsus using any size of telescope when the moon is fully illuminated.

Hello, Moon in June Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of June 12th, 2022 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

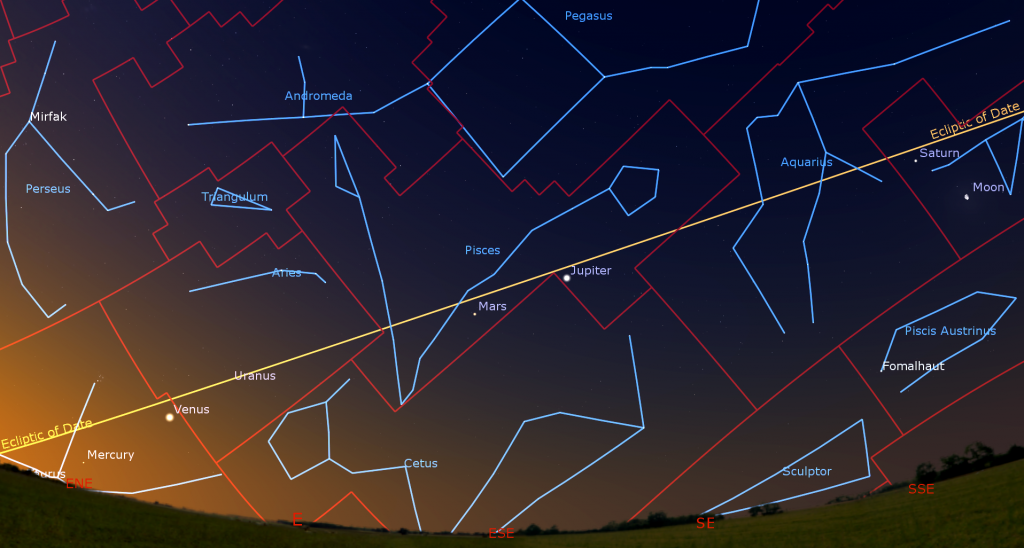

This week will feature a full Strawberry Supermoon (that won’t look pink). There are plenty of interesting sights to see on our natural nightlight while it’s full. Mercury will stretch to its widest angle from the morning sun, allowing all five bright planets to be visible, in their order – plus an asteroid and the two ice giant planets! And I update two evening comets that are available for telescope owners. Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon

Night owls worldwide this week will be accompanied by the bright moon. Our natural satellite will wax to full and then wane toward its third quarter phase next week.

Tonight (Sunday, June 12) observers in the northeastern USA and eastern Canada can see the 97%-full moon pass in front of (or occult) the bright double star named Dschubba or Delta Scorpii in binoculars and backyard telescopes! That star is the central claw star of the scorpion. Exact timings will vary by location, so use Stellarium or another astronomy app to determine the precise times for your city. In Toronto, the thin strip of darkness on the bottom of the moon will cover the two stars at 10:14:40 pm EDT. If you view that ingress event in a backyard telescope, Dschubba’s two stars will wink out 8 seconds apart! At 10:55:26 pm EDT the pair of stars will emerge, about 5 seconds apart, from behind the moon’s bright right-hand limb near the big crater named Furnerius.

The moon will be in the lower part of the southern sky – so you may need to walk around to obtain an unobstructed view of it. Start watching a few minutes ahead of each time noted. I posted a diagram of the beginning of the event here last week. I’ve included a diagram of the stars emerging (or egress) so you’ll you know where to look for them. The stars’ re-appearance position will shift lower on the moon’s edge for more southerly observers than Toronto, and higher if you’re viewing the event from farther north.

The bright moon will spend Monday night passing through the southerly stars of Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer), the overlooked thirteenth zodiac constellation. (The sun shines among those same stars in mid-June every year.) Watch for the bright reddish star Antares, the heart of the scorpion, shining a palm’s width to the moon’s upper right (or celestial west) that night. The moon will look like it’s full on Monday night, but a close inspection will reveal a thin strip of unlit terrain along its western (lower left) edge.

The moon will officially reach its full phase at 7:52 am EDT (or 4:52 am PDT and 11:52 Greenwich Mean Time) on Tuesday. The June full moon always shines in or near the stars of southern Ophiuchus or next-door Sagittarius (the Archer). When the moon rises at sunset many hours later in the Americas, it will already be waning – showing a thin, dark strip along its eastern (upper right) limb. Try viewing the moon in binoculars or a telescope on both nights and note the change! Moon phases occur independently of Earth’s rotation – so while the Americas will not see the moon while it’s precisely full, observers across central Asia will!

The June moon will occur only half a day before the moon is closest to Earth for the month (or lunar perigee), producing higher tides worldwide and the first of two consecutive supermoons for 2022. Supermoons shine about 16% brighter and appear about 6% larger than an average full moon.

Every culture around the world has developed its own teachings about the full moon, and has assigned special names to each moon, which marked time and lit the way of hunters and travelers at night before modern conveniences like flashlights. The indigenous Ojibwe people of the Great Lakes region call this moon Ode’miin Giizis, the Strawberry Moon. For the Cree Nation it’s Opiniyawiwipisim, the Egg Laying Moon (referring to the activities of wild water-fowl). The Mohawks call it Ohiarí:Ha, the Fruits are Small Moon. The Cherokee call it Tihaluhiyi, the Green Corn Moon, when crops are growing. English-speaking, non-indigenous groups commonly use Strawberry Moon, Mead Moon, Rose Moon, Birth Moon, or Hot Moon.

When you face a full moon, the sunlight shining on it is coming from directly behind you – the same way the projector in the rear of a cinema lights up the movie screen in front of you. That sunlight is arriving straight-on to the moon’s surface – from directly overhead if you were standing on the moon -so it doesn’t generate any shadows. Every variation in brightness and colour we see on a full moon is due entirely to the moon’s geology, not its topography! That means we can easily distinguish the dark, grey basalt rocks from the bright, white, aluminum-rich anorthosite rocks.

The basalts overlay the various lunar maria, Latin for “seas” – a term coined because people thought they were water-filled before telescopes revealed otherwise. The maria are giant basins excavated by major impactors early in the moon’s geologic history and then infilled with dark basaltic rock that upwelled from the interior of the moon later in the moon’s geological history.

The much older and brighter parts of the moon are composed of anorthosite rock. Those areas are higher in elevation and are heavily cratered because there is no wind and water, or plate tectonics, to erase the scars of impacts. Lunar scientists use the number of craters in a given location to gauge its age (more craters means older). By the way, the highlands’ bright, white appearance is produced by sunlight reflecting off of the crystals the rock is made of – the same sort of big crystals you can find in the polished granite countertops in Earth’s kitchens. And yes, there are coloured rocks on the moon.

Some of the violent impacts that blasted craters in the highland regions also threw bright streams of ejected material far outward and onto the darker maria. We call those streaks lunar ray systems. Some rays are thousands of km in length – like the ones emanating from the very bright crater Tycho in the moon’s southern central region. Use your binoculars to scan around the full moon for the smaller ray systems everywhere!

There are also places where maria craters have thrown dark rays onto white rocks. And, since the dark basalt overlays the white, older rock beneath them, you can find lots of craters where a hole has been punched through the dark rock, producing a white-bottomed crater! Any size of telescope will show them. Just pan around.

Several of the maria link together to form a curving chain across the northern half of the moon’s near-side. Mare Tranquillitatis, where humanity first walked upon the moon, is the large, round mare in the centre of the chain. You can plainly see that this one is darker and bluer than the others, due to its basalt being enriched in the mineral titanium. That’s one of the reasons why Apollo 11 was sent to land in it. (The other was that it is close to the moon’s equator, making the orbital mechanics easier.)

By the way, Earth-bound telescopes – even the largest ones – cannot see the items left by the astronauts on the moon. When the air is particularly steady, the smallest feature you can see on the moon with your backyard telescope is about 2 to 6 km across – far larger than any lunar module descent stage, which are only about 4 metres across. Only cameras on spacecraft in orbit around the moon can photograph the Apollo astronauts’ footprints, lunar rover tracks, and equipment. The upcoming Artemis missions to the moon will focus on the polar regions where water frozen in permanently shadowed craters can be harvested.

While the moon is almost fully illuminated this week, use your telescope to look at the dark stains left behind by extinct volcanoes on the moon! Alphonsus is a 110 km wide crater located just south of the moon’s centre, on the upper right shore of Mare Nubium. Any size of telescope will reveal a triangle formed by numerous dark spots on the crater’s floor near its left and right rims. Those are ash deposits. Another crater with similar markings is Atlas, which sits in the northern region of the moon, about halfway between the northern shore of Mare Serenitatis and the edge of the moon.

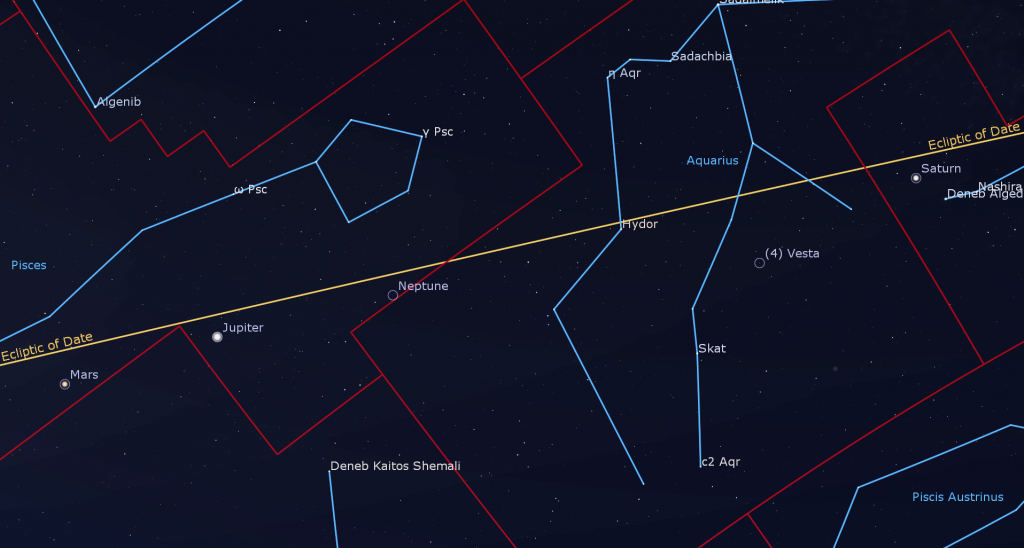

The now-waning gibbous moon will continue to visit the stars of Sagittarius (the Archer) on Tuesday and Wednesday night, but it won’t rise until nearly midnight. On Thursday and Friday night, the moon will cross the dull stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). But Friday will kick off the moon’s monthly trip past the bright planets. Early risers can see the creamy-yellow dot of Saturn shining a palm’s width to the moon’s upper left (or 6 degrees to the celestial northeast) until almost sunrise on Saturday morning.

After 24 hours of easterly travel, on Sunday morning, the waning moon will pass within a thumb’s width below (or 1.5 degrees south of) the main belt asteroid designated (4) Vesta. That’s close enough for the moon and magnitude 6.75 Vesta to share the view in a widefield telescope eyepiece. When they first clear the treetops in the east-southeastern sky, Vesta will be positioned to the moon’s upper left. The diurnal rotation of the sky will lift Vesta above the moon by 4 am local time. Observers in most of Antarctica, the tip of South America, and the Falkland Islands can see the moon occult Vesta around 08:00 GMT.

The Planets

You may have seen reports on social media about five planets lined up in the morning sky, in the order of their distance from the sun. It’s true, but there’s a catch. At mid-northern latitudes, as we near the June solstice on Tuesday, June 21, the sun rises very early. All around the world at the latitude of Toronto, sunrise will occur at 5:35 am local time this week. Okay, not too bad – but the sky begins to brighten, with the onset of nautical twilight, by 4:15 am! So if you want to enjoy those planets, check the morning cloud forecast and then set the alarm clock.

Saturn will rise first. Its creamy yellow dot will start to gleam above the east-southeastern horizon around 1 am in your local time zone. None of the stars around it in eastern Capricornus (the Sea-Goat) are bright enough to compete. Saturn will remain in view as it climbs higher and shifts south until the dawn twilight hides it at about 5 am. Any size of telescope will show you Saturn’s globe extending above and peeking out below its rings, and up to a handful of its moons arrayed all around the planet. Saturn is now moving slowly westward in a retrograde loop that will last until late October.

The main belt asteroid named (4) Vesta will be traveling a fist’s width to the lower left (or about 10° to the celestial east) of Saturn – but you’ll need to hunt for it with good binoculars or a backyard telescope before 4:30 am in order to see its magnitude 7.1 speck. Next in line, the blue planet Neptune, which is half as bright as Vesta, will be lurking a fist’s width to Jupiter’s upper right (or 10° to the celestial west-southwest).

Shortly after 2 am local time, the very bright, white planet Jupiter will peek above the eastern horizon to join the planet conga line. Being that much brighter, Jupiter will remain visible until almost sunrise, but the faint stars of Pisces (the Fishes) it is swimming with, will not. Jupiter’s large globe, 11 times wider than Earth, will be flanked by its retinue of four Galilean moons. The planet will sport dark bands running parallel to its equator, the Great Red Spot on Tuesday, Friday, and next Sunday morning, and the small back shadow of Europa’s shadow will cross Jupiter on Friday morning.

Just before 3 am local time, Mars will appear as a medium-bright, reddish dot shining a generous palm’s width to Jupiter’s lower right in Pisces. Mars’ distance from Jupiter will increase a little every morning. In a telescope, Mars will shine with a tiny, 86%-illuminated disk. The red planet will also be brightening very slowly and growing larger as Earth’s faster orbit draws us closer to it.

Uranus is next in line, but its magnitude 5.85, blue-green dot won’t be very visible until month’s end, when it will have a chance to climb higher before twilight begins. On Monday morning, Uranus will rise about 10 minutes before extremely bright, white Venus appears low in the east-northeastern sky. Uranus will sit only two finger widths above Venus then, but that brighter planet’s sunward swing will carry it rapidly away from Uranus every morning. By sunrise, Venus will gleam above the treetops. Venus will exhibit a nearly-round shape when viewed in a telescope or in good binoculars.

Last to rise will be Mercury, at about 4:30 am local time. Look for the speedy planet’s much fainter dot positioned about a fist width to Venus’ lower left (or celestial east). Mercury’s position well below (or celestial south of) the slanted morning ecliptic will prevent observers at mid-northern latitudes from seeing the speedy planet very easily, even when it swings farthest from the sun on Thursday morning. If you want to make the attempt, try to catch it by 5 am.

That line of planets will last for the rest of June. Don’t forget that the waning moon will shine near Saturn and Vesta on the coming weekend. Turn all optics away from the east before sunrise, please!

Faint Comet Update

Last week I wrote about two comets that are currently observable in backyard telescopes in the evening sky, especially if you view them in non-light-polluted skies. In smaller telescopes, comets resemble fuzzy grey stars. In larger telescopes, you might see a hint of green colour and a hint of its tail pointed away from the sun.

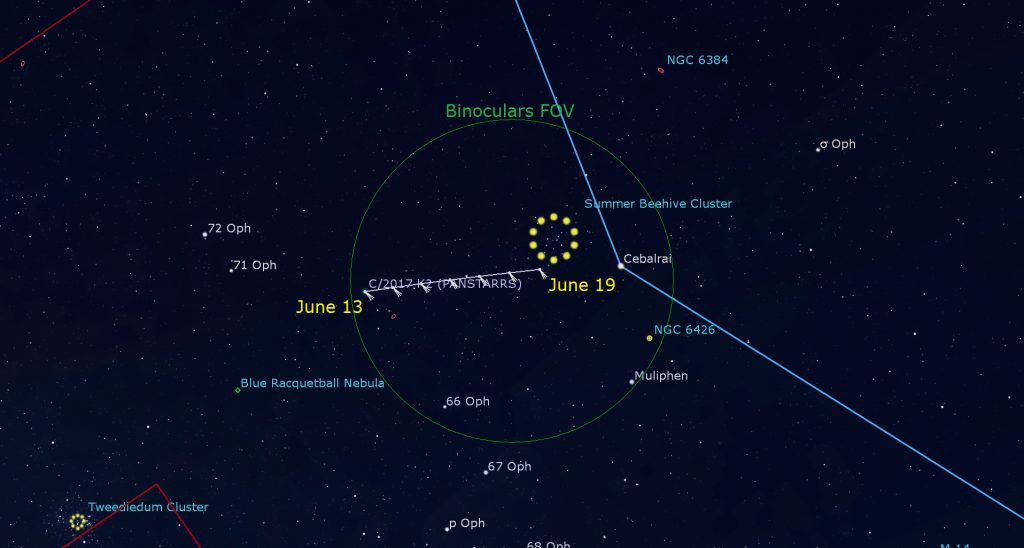

The brighter of the two comets, named C/2017 K2 (PanSTARRS), is travelling left to right (or celestial southwestward) through northeastern Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer). Look for it about one-third of the way up the southeastern evening sky. The comet is visible all night long, but it will be most easily seen while it is highest in the sky, during the wee hours. It is currently around magnitude 9.4 and still brightening. To start this week, the comet will be located several finger widths to the left (or 5° to the celestial northeast) of the bright star Cebalrai. It will pass the southern edge of open star cluster named IC 4665 (the Summer Beehive Cluster) on June 19-20 and close to the bright star Cebalrai on June 21-22. By then the moon will not be so bothersome.

The fainter, more challenging comet named C/2021 P4 (ATLAS) is travelling right to left (or celestial southeastward) below the constellation of Lynx, which reclines low in the northwestern sky until about 1 am local time. This one is currently at a faint magnitude 11 and brightening. Try to view it as soon as the sky darkens fully, when it will be located below the Big Dipper’s bowl. There aren’t really any “landmarks” to help you find it, but it will be travelling to the left of the medium-bright star named 21 Lyncis this week. It will fly just above NGC 2683 (the UFO Galaxy) on July 5.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

RASC’s Public sessions at the David Dunlap Observatory may not be running at the moment, but they are pleased to offer some virtual experiences instead in partnership with Richmond Hill. The modest fee supports RASC’s education and public outreach efforts at DDO. Only one registration per household is required. Prior to the start of the program, registrants will be emailed the virtual program link.

On Friday night, June 17 from 9:30 to 11 pm EDT, tune in for DDO Up in the Sky. During the family-friendly session, RASC astronomers will live-stream views through their telescopes and the giant 74” telescope at DDO (pre-recorded views will be used if skies are cloudy). Only one registration per household is required. Deadline to register for this program is Wed., June 15, 2022 at 3 pm. Prior to the start of the program, registrants will be emailed the virtual program links. More information is here and the registration link is here.

On Sunday afternoon, June 19 from 12:30 to 1 pm EDT, tune in for DDO Sunday Sungazing. Safely observe the sun with RASC, from the comfort of your home! During these family-friendly sessions, a DDO Astronomer will answer your questions about our closest star: the sun! Learn how the sun works and how it affects our home planet. Live-streamed views of the sun through small telescopes will be included, weather permitting. Only one registration per household is required. Deadline to register for this program is Wednesday, June 15, 2022 at 3 pm. Prior to the start of the program, registrants will be emailed the virtual program links. More information is here and the registration link is here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, July 5 at 3:30 pm EDT, when we’ll celebrate Canadians in the Stars and a summer planet preview! Plus, we’ll continue with our Messier Objects observing certificate program and share some galaxy-viewing tips. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Space Station Flyovers

The ISS (or International Space Station) will not be visible gliding silently over the GTA this week.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!