See Solar System Sparkles, Valentine’s Night Delights, and Full Snow Moon Features While the Love Goddess Gleams at Dawn!

This beautiful image shows the glowing pink hydrogen gas of the Rosette Nebula (NGC 2237) in Monoceros (the Unicron) and its internal star cluster NGC 2244. It was captured by Stan Noble of Swift Current, Saskatchewan in 2017/18. The Rosette, which covers about a thumb’s width of sky, can be seen in binoculars in a dark sky. It’s located about a fist’s diameter to the left of Betelgeuse in Orion. More of his images can be enjoyed on his Astrobin page at https://www.astrobin.com/users/stannoble/

Greetings, Lovers of Astronomy!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of February 13th, 2022 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. I repost these emails with photos at http://astrogeo.ca/skylights/ where the old editions are archived. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific new book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will dominate the night skies as it passes the Full Snow Moon phase at mid-week – so I highlight some stormy sights to see on it. That won’t stop us from seeing the Zodiacal Light and a few romantic star sets, though. Meanwhile, Jupiter and the ice giant planets sink after sunset, and maximum Mercury joins Venus and Mars before sunrise. Read on for your Skylights!

Evening Zodiacal Light

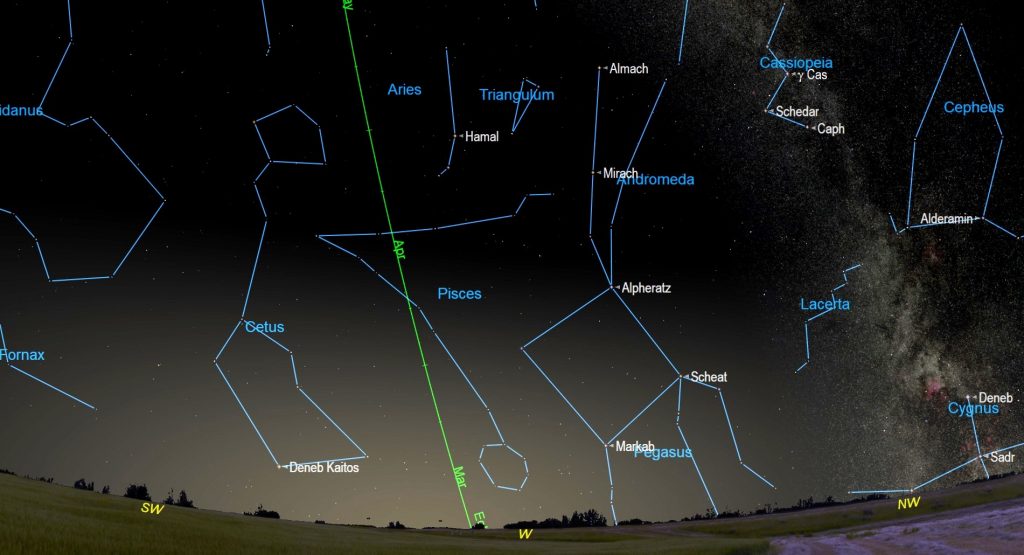

If you live in a location where the sky is free of light pollution, you might be able to spot the Zodiacal Light, which will appear during the two weeks that precede the new moon on March 2. After the evening twilight has disappeared, you’ll have about half an hour to check the western sky for a broad wedge of faint light extending upwards from the horizon and centered on the ecliptic. That glow is the zodiacal light – sunlight scattered from countless small particles of material that populate the plane of our solar system. Don’t confuse it with the brighter Milky Way, which extends upwards from the northwestern evening horizon at this time of year.

The Moon

The moon will flood night skies worldwide with light this week. Our natural satellite will kick off the week among the stars of Gemini, where it will be completing a passage across the Winter Football asterism. Tonight (Sunday), use binoculars to view the golden star Pollux and its white “twin” Castor arrayed a generous palm’s width above (or celestial NNW of) the bright, 93%-illuminated moon. The moon shifts east by one lunar diameter per hour. At about 10 pm EST on Superbowl night, the moon will form a straight line with those two stars!

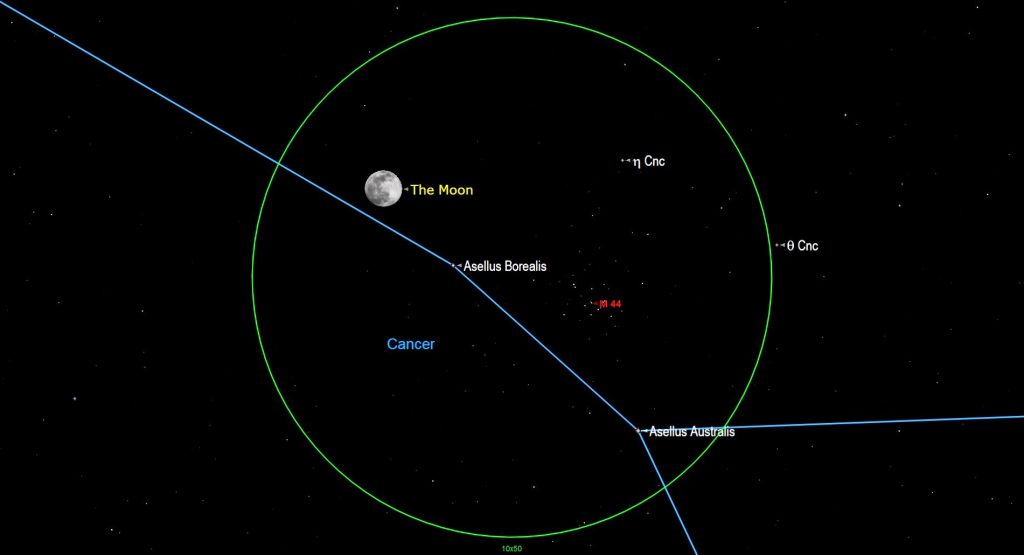

After dusk on Monday, the nearly full moon will hop east to take up a position a few finger widths to the upper left (or 3 degrees to the celestial north) of the large open star cluster known as The Beehive (and Messier 44) in the constellation of Cancer (the Crab). Encounters between M44 and the moon or planets occur frequently because the cluster is located only one degree north of the ecliptic. The moon and the Beehive will both fit within the field of view of binoculars, but the moon’s brilliance will mostly overwhelm the cluster’s stars. To see more of them, try hiding the moon just outside your optics’ field of view. During the night, the diurnal rotation of the sky will shift the moon above the Beehive.

From Tuesday to Thursday, the very bright moon will cross the constellation of Leo (the Lion) and its brightest star Regulus. The moon will officially pass its full phase at 11:56 am EST (or 16:56 Greenwich Mean Time) on Wednesday morning in the Americas. So, for observers there, the moon will look just a sliver less than full on both Tuesday and Thursday evenings. The thin, non-illuminated strip along the edge of the moon will switch from the moon’s lower left (lunar west) side on Tuesday to the moon’s upper right (lunar east) side on Wednesday. That’s because the moon’s angle from the sun (or elongation) will change from 172° to 187° in 24 hours – i.e., crossing the 180° position).

When full, the moon always rises around sunset and sets around sunrise because it is opposite the sun. The February full moon always shines in or near the stars of Leo (the Lion), which is half the sky away from the sun in the stars of Capricornus (the Sea-Goat). Winter moons also climb very high in the night sky because the winter sun is so low at noon.

The moon has always shone down upon humans on Earth. At some point, people began to seek to understand our natural environment and to take advantage of the annual variations in the seasons to schedule planting, harvesting, hunting, and celebrating life events. The twelve (sometimes thirteen) full moons per year acted as obvious celestial markers. The full moon’s bright light allowed people to be out and about safely at night. It lit the way of the hunter or traveler before modern conveniences like electric lights, and workers in the fields devoting extra hours to get the harvest in. By the way – those extra, thirteenth full moons, which fall into different months each year, are commonly referred to as blue moons. The next one will happen in August, 2023.

Each society around the world developed its own set of stories for the moon, and every month’s full moon now has one or more nick-names related to human spirit or the natural environment. The indigenous Anishnaabe (Ojibwe and Chippewa) people of the Great Lakes region call the February full moon Namebini-giizis “Sucker Fish Moon” or Mikwa-giizis, the “Bear Moon”. For them it signifies a time to discover how to see beyond reality and to communicate through energy rather than sound. The Algonquin call it Wapicuummilcum, the “ice in river is gone” moon. The Cree of North America call it Kisipisim, the “the Great Moon”, a time when the animals remain hidden away and traps are empty. For Europeans, it is known as the Snow Moon or Hunger Moon.

Looking at the moon through binoculars and telescopes this week will show you the huge difference in the way sunlight illuminates the moon. Every month around first quarter, the sun’s rays strike the moon from the side. In the zone alongside the pole-to-pole terminator line that separates the lit and dark hemispheres, the sun is just rising over the moon’s eastern horizon. With no atmosphere to scatter light, the shadows cast by every crater rim, mountain, and ridge are a deep black – and even very small bumps and ridges are highlighted, revealing otherwise hidden features on crater floors.

This week, when the moon is close to fully illuminated, the sunlight striking the moon will be coming from directly “behind you”, especially when you face the full moon. It’s analogous to the way the projector in the rear of a cinema lights up the movie screen in front of you. That sunlight is arriving straight-on to the moon’s surface, so it doesn’t generate any shadows. Every variation in brightness and colour you see on a full moon is due entirely to the moon’s geology, not its topography! At that time, you can easily distinguish the dark, grey, basalt rocks from the bright, white, aluminum-rich anorthosite rocks.

The basalts overlay the various lunar maria, Latin for “seas” – coined because people used to think they were water-filled. The maria are basins excavated by major impactors early in the moon’s geologic history and later flooded with molten rock that upwelled from the interior of the moon late in the moon’s geological history. That filling happened in stages. A backyard telescope will easily reveal terraces of lava that “froze” after each incursion – but those are best seen when the moon isn’t full.

The much older and brighter parts of the moon are composed of anorthosite rock. Those areas are higher in elevation and are also heavily cratered – because there has been no wind and water, or plate tectonics, to erase the scars of countless impacts. By the way, the bright, white appearance of anorthosite is produced by sunlight reflecting off of the crystals the rock is made of – the same sort of crystals you see in the granite countertops in Earth’s kitchens. And yes, there are coloured rocks on the moon.

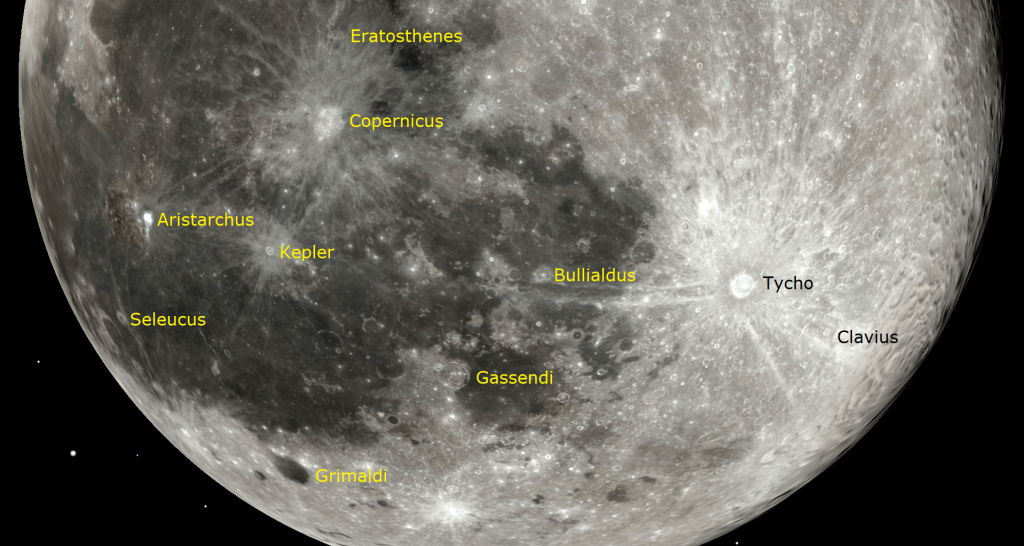

Some of the violent impacts that created the craters in the highland regions also threw bright streams of ejected material long distances on top of the darker maria. We call those streaks lunar rays systems. Some rays are thousands of km in length – like the ones from the very bright 100 million-year-old crater Tycho in the moon’s southern central region.

Use your binoculars to scan around the moon this week. There are large and small ray systems everywhere! There are also places where craters recently blasted into the maria have tossed dark rays onto white rocks. And, since the dark basalt overlays the white, older rock underneath it, a small telescope will show lots of craters where a hole has been punched through the dark rock, producing a white-bottomed crater!

Several of the maria link together to form a curving chain across the northern half of the moon’s near-side. Mare Tranquillitatis the “Sea of Serenity”, where humankind first walked upon the moon, is the large, round mare in the centre of the chain. Sharp-eyes might detect that this mare is darker and bluer than the others, due to enrichment of the basalt by the metal titanium. That’s one of the reasons why Apollo 11 was sent there.

Now that you know more of the lunar terminology, here are some additional things to watch for…

This week will also be ideal for viewing the prominent crater Copernicus in eastern Oceanus Procellarum, the “Ocean of Storms”, which is the large dark region located south of large Mare Imbrium. Copernicus is located slightly to the upper left (lunar northwest) of the moon’s centre. The Jesuit priest Giovanni Battista Riccioli, who published a labelled map of the moon in 1651, deliberately placed the craters named for astronomers Nicolaus Copernicus and Johannes Kepler, their defender Ismaël Bullialdus, and the Greek philosophers Aristarchus, Eratosthenes, and Seleucus, into the Ocean of Storms because they all dared to suggest that Earth revolved around the sun – in contravention to the church’s teachings. Riccioli honoured his fellow Jesuits Grimaldi and Clavius with prominent craters elsewhere on the moon.

The 800 million year old crater Copernicus is visible with unaided eyes and binoculars – but telescope views will reveal many more interesting aspects of lunar geology. Several nights before and after the moon reaches its full phase, Copernicus will exhibit heavily terraced edges (due to slumping), an extensive ejecta blanket outside the crater rim, a complex central peak, and both smooth and rough terrain on the crater’s floor. Around full moon, Copernicus’ rather ragged ray system, which extends 800 km in all directions, becomes prominent. Use high magnification to look around Copernicus for small craters with bright floors and black haloes – caused by impacts through Copernicus’ white ejecta that excavated dark Oceanus Procellarum basalt and even deeper highlands anorthosite.

The prominent crater Kepler is located to the lunar west of Copernicus. Smaller, but brighter Aristarchus is positioned north of them. It is one of the most colourful regions on the moon. NASA orbiters have detected high levels of radioactive radon at Aristarchus.

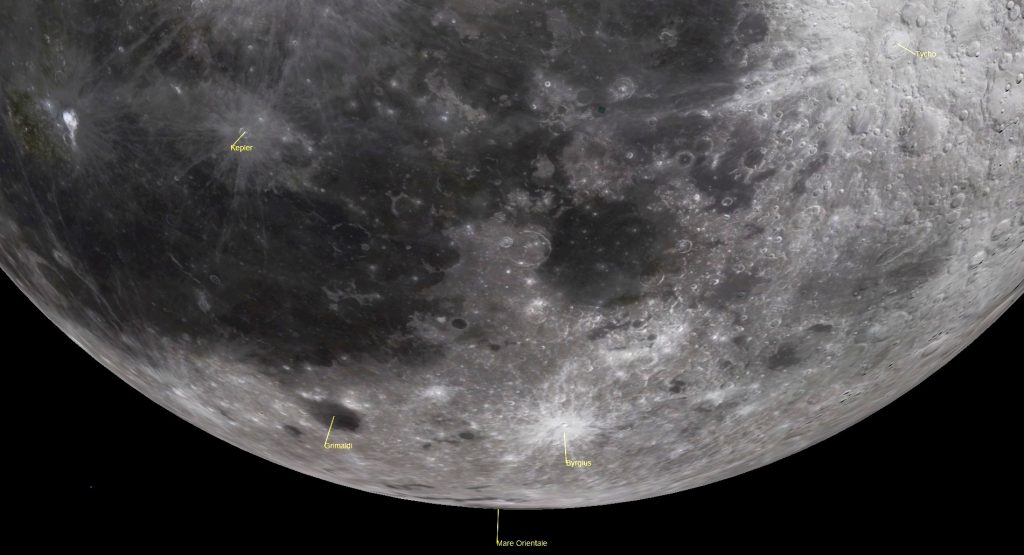

From Friday through Sunday, the bright, waning moon will rise in late evening within the big constellation of Virgo (the Maiden). I’ve recently written about the lunar libration effect that lets us see an extra 9% of the moon’s total surface without leaving the Earth. On Friday night, the western limb of the moon will be rotated towards Earth, revealing the edge of Mare Orientale, the youngest of the moon’s great basins. Its name “the Eastern Sea” belies its location on the moon’s western hemisphere. To see it, use binoculars or a telescope to first seek out the dark circular crater Grimaldi and the very bright, small crater Byrgius to its south. Mare Orientale will be a darkened strip hugging the edge of the moon between those two craters.

The Planets

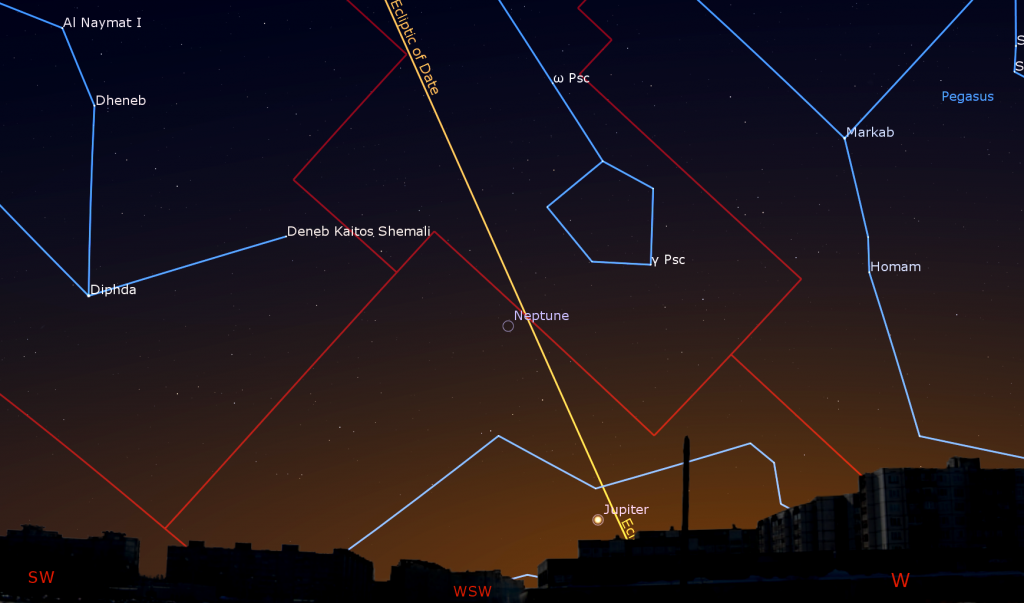

This week offers our last chance to glimpse Jupiter before it becomes completely hidden in the western post-sunset glow. We’ll have to wait until Saturn returns in August to see another bright evening planet. Jupiter and Mars won’t reappear in evening until autumn. The bright dot of Jupiter will shine just above the west-southwestern horizon for a short time after sunset. It’ll drop a little lower each night. Neptune, positioned only a fist’s diameter above (celestial east of) Jupiter, will be too faint and small to easily see when it’s that low in the sky. It, too, will be shifting sunward night-by-night.

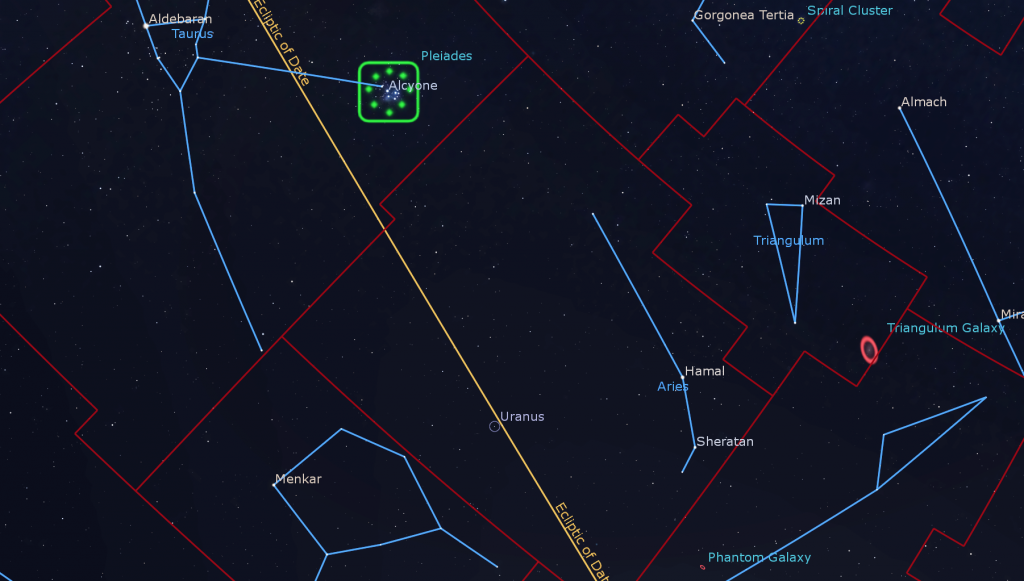

You can seek out magnitude +5.8 Uranus after the sky fully darkens, at around 7:30 pm local time. It can be seen easily in binoculars and backyard telescopes – and even with your unaided eyes on dark, clear nights – if you know where to look. The planet’s small dot will be positioned a fist’s width to the left of (or 11 degrees to the celestial southeast of) Aries’ brightest stars, Hamal and Sheratan. In fact, it’s almost exactly midway along a line connecting Hamal with the bright star Menkar in Cetus (the Whale). Around 7:30 pm local time, Uranus will sit halfway up the southwestern sky. By 9 pm local time, it’ll be too low for decent views.

The rest of the planets are partying in the pre-dawn sky.

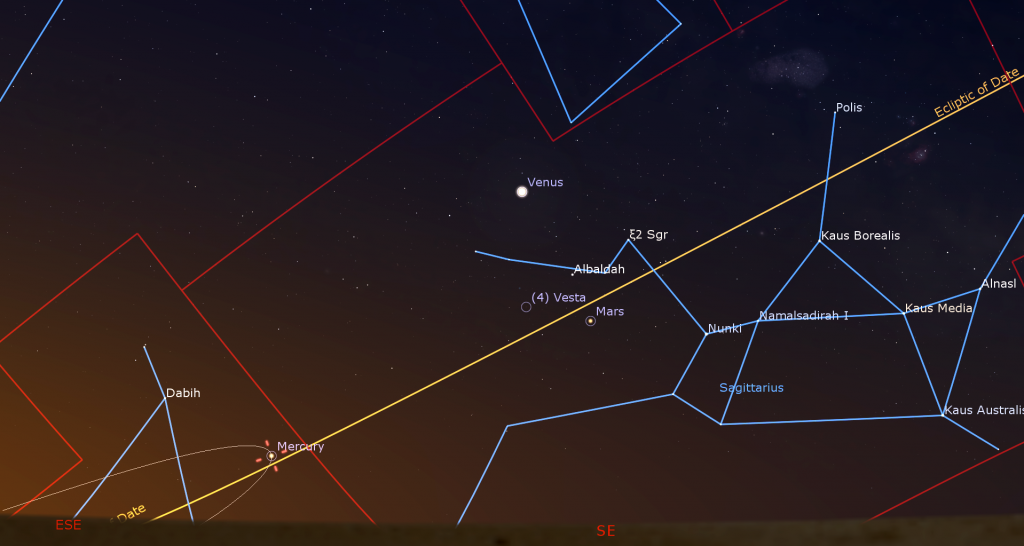

Early risers will enjoy seeing brilliant Venus gleaming in the southeastern sky near the teapot-shaped constellation of Sagittarius (the Archer). It will rise shortly before 5 am local time and remain visible until dawn. 300 times fainter Mars will be rising about half an hour later than Venus. During the coming several weeks, the reddish planet will be parked a palm’s width to Venus’ lower right (or 6° to the celestial south). Both planets will be travelling eastward, on gradually converging, parallel tracks, but at the same time they will be slowly increasing their angle from the sun, and rising earlier. The minor planet designated (4) Vesta will dance a few finger widths to Mars’ left, and will slowly draw closer to Mars during this week.

The speedy planet Mercury will rise at around 6 am local time this week. If you have an unobstructed view of the southeastern horizon, you can look for the medium-bright planet shining about 1.5 fist diameters to the lower left of Mars and Venus. On Wednesday, Mercury will reach its widest angle of 26° west of the sun, and peak visibility for its current morning apparition. In a telescope Mercury will exhibit a 59%-illuminated, waxing gibbous phase. (Be sure to turn all optics away from the eastern horizon before the sun rises.) Mercury’s position near the shallowly-dipping morning ecliptic will make this a poor display for mid-Northern latitude observers, but a fine appearance for anyone located near the Equator, and farther south. Mercury will be nearly as far from the sun on the surrounding mornings.

Valentine’s Night Treats

While none of the official constellations are heart-shaped, there are some romantic duos in the stars that you can see with your unaided eyes on Valentine’s Day night – despite the bright moonlight.

If you look about halfway up the western sky during mid-evening you’ll see the stars of Princess Andromeda extending upwards from the top corner of the big square of Pegasus. Andromeda’s hero, and eventual husband, Perseus is the constellation directly above her. Its centre is marked by the bright star Mirfak. Between those lovers, and a few fist diameters to their right (or 30° to the celestial northwest of them), are her parents’ constellations, w-shaped Queen Cassiopeia and boxy King Cepheus. I told their story here.

To celebrate fraternal love, we have the constellation of Gemini (the Twins) located in the evening sky to the upper left (or celestial northeast) of Orion (the Hunter). The two medium-bright stars Pollux (the lower one) and Castor (the upper one) mark the heads of the two brothers. Note that Pollux is a wee bit brighter and warmer in colour than Castor. Viewed through your telescope, Castor splits into a nice double star.

For a different type of devotion, we can highlight Orion the hunter’s faithful companion Canis Major (the Big Dog). Canis Major forever and faithfully follows his master around the sky – although he might be more interested in chasing Lepus (the Hare), the constellation that sits to his west, below Orion. The big dog’s stars are distributed around their brightest member, Sirius, also known as the Dog Star (and Alpha Canis Majoris). On mid-February evenings, Sirius reaches its highest point over the southern horizon at around 9:30 pm local time – while sparkling like a diamond! Sirius is a hot, white, A-class star located only 8.6 light-years from Earth – part of the reason for its brilliance. For mid-northern latitude observers, Sirius is always seen in the lower third of the sky, through a thicker blanket of refracting atmosphere. This causes the strong twinkling and flashes of color the Dog Star is known for.

Look less than a finger’s width to the lower right of the bright star Alnitak – the star at the eastern, left-hand end of Orion’s Belt – for a medium-bright star named Sigma Orionis or σ Ori. When viewed in powerful binoculars or a backyard telescope, you’ll see that Sigma Orionis is in the middle of a pretty little group of about 10 stars arranged in a dart shape – like Cupid’s Arrow!

Wait until next week’s moonless nights for the following romantic targets. Beside Orion, on his eastern (left) side, and above Canis Major, is the constellation of Monoceros (the Unicorn). Its stars are mainly of medium and low brightness – but it sits squarely astride the Milky Way and contains some delightful sights! The Rosette Nebula (also known as NGC 2244) is a beautiful rose-shaped cloud of reddish gas with a clump of bright little stars in its centre. It is located about a fist’s diameter to the left of Orion’s shoulder star Betelgeuse. The Rosette is visible in binoculars, but only long-exposure photos will reveals its colourful rose.

A little star named Theta Canis Majoris sits a palm’s width to the upper left of Sirius. It marks the doggy’s nose! If you draw an imaginary line from Sirius to Theta and then double its length, you’ll come to a small open star cluster named Messier 50, also known as the Heart-Shaped Cluster and NGC 2323. The cluster is visible in binoculars – but try viewing it through your telescope. I don’t think that the heart shape is all that obvious – but the cluster of mainly white stars features the special treat of a bright, golden star at its lower edge.

Cassiopeia (the Queen) hosts the Heart Nebula, also known as the Valentine Nebula and IC 1805. It’s a truly beautiful object located 2,500 light-years away from us. This nebula and its companion the Soul Nebula (IC 1848) are located between Perseus and Cassiopeia – about three finger widths to the right of the Double Cluster. It’s too faint to see unless the sky is very, very dark – but many lovely photographs of it have been published. A faint, but rich star cluster named Caroline’s Rose (NGC 7789), named for female astronomer Caroline Herschel, sits a few degrees below the bottom stars of Cassiopeia.

Finally, to celebrate your favorite someone, locate and view their Birthday Star. That’s a star that is located at the same distance from Earth (expressed in light-years) as that person’s age in years. In other words, the light you see now started its journey towards us at the time they were born. Visit this page and scroll down the list to find birthday stars for different years old – or use this page to enter a birth date. Then you can look for that star in the night sky – if it happens to be visible at this time of year from your location. It’s fun! And the stars for kids’ ages tend to be the closest and brightest stars in the night sky – and easy to see, even from the city.

Happy Valentine’s Day!

Telescope Tips for Cold Weather Observing

If you missed last week’s tips about using your telescope where it’s extremely cold outside, it’s posted here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory YouTube channel.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Samantha Jewett of RASC National returns on Tuesday, February 15 at 3:30 pm EST, when we’ll welcome special guests Isaac Murdock from Serpent River First Nation to talk about the importance of the night sky, how it is still used today to understand our roles and responsibilities here on Earth, how celestial objects are used to aid in navigation, and more! Educator Jodie Williams will introduce Lessons From Beyond, a new and unique collaborative network of Indigenous educators, Elders, academics, and scientists from across North America as well as New Zealand, and also includes a partnership with NASA. And – we’ll continue with our Messier Objects observing certificate program. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

On Tuesday night, February 15 from 8 to 9 pm EDT, SkyNews Magazine editor Allendria Brunjes and Canadian astrophotographer Paul Owen will host Subs and Stars – Lesson 5 of a free, eight-part online series on astrophotography. This session will cover image processing of the beautiful Orion Nebula from data collected by RASC’s Robotic Telescope. Details are here, and the Zoom registration link is here.

On Wednesday evening, February 16 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will live stream their monthly Speakers Night meeting. This month will feature Vivian Yun Yan Tan, MSc, PhD Candidate, York University. Her talk is titled A Brief History of Galaxy Quenching over Cosmic Time. Everyone is invited to watch the presentation live on the RASC Toronto Centre YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Saturday afternoon, February 19, from 1 to 2:30 pm EST, RASC National will celebrate Black History Month with the free public live stream To the Stars and Beyond, showcasing black excellence in STEM and STEM education with an awesome lineup of speakers from the Black community. Details are here.

Public sessions at the David Dunlap Observatory may not be running at the moment, but they are pleased to offer some virtual experiences instead in partnership with Richmond Hill. The modest fee supports RASC’s education and public outreach efforts at DDO. On Saturday night, February 19 from 7:30 to 9:00 pm EDT, tune in for DDO Up in the Sky. During the family-friendly session, RASC astronomers will live-stream views through their telescopes and the giant 74” telescope at DDO (pre-recorded views will be used if skies are cloudy). Only one registration per household is required. Deadline to register for this program is Wed., February 16, 2021 at 3 pm. Prior to the start of the program, registrants will be emailed the virtual program links. The registration link is here.

Don’t forget to take advantage of the astronomy-themed YouTube videos posted by RASC Toronto Centre and RASC Canada.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!