The Crescent Moon Cruises Post-sunset Planets, Pluto Peaks, and Admiring the Summer Milky Way!

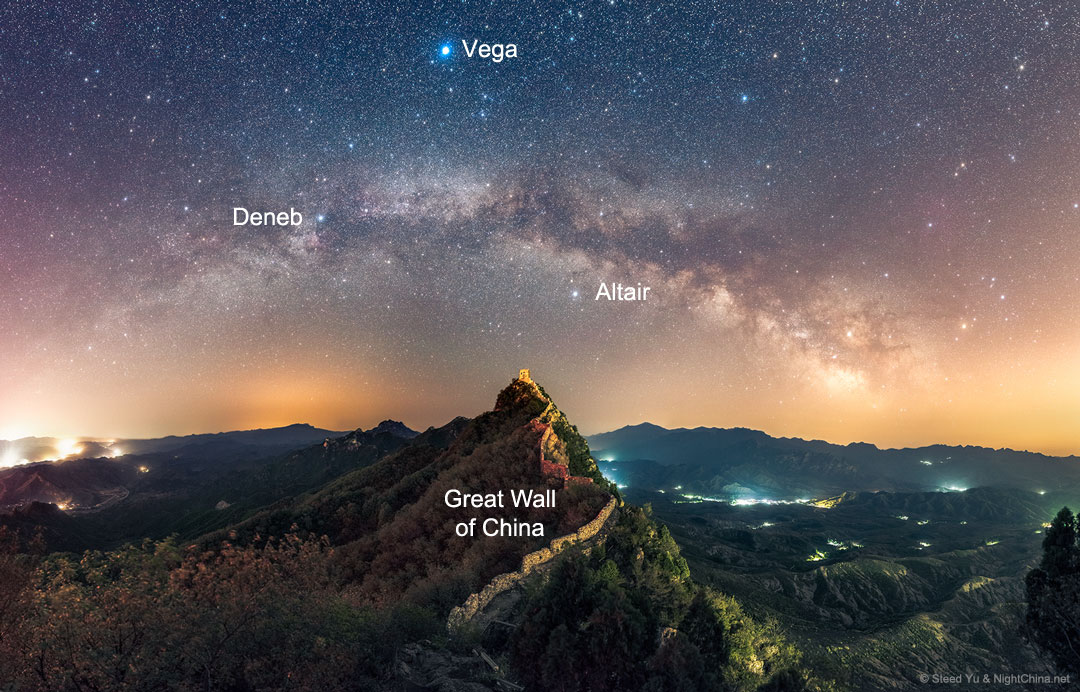

This beautiful annotated image of the summer Milky Way arching over the Great Wall of China was captured by Steed Yu. The bright star at centre far right is Antares. It’s little claw stars shine to its upper right. The dark dust patches and lanes are apparent. It was the NASA APOD for July 3, 2017. More of his images may be viewed at https://www.astrobin.com/users/Steed/ and at http://nightchina.net/

Hello, Mid-July Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of July 16th, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The young crescent moon will join the western, post-sunset planets this week, leaving the rest of the nights moonless and ideal for admiring the splendors of the Milky Way. While Mercury climbs, Venus and Mars sink sunward, Pluto reaches maximum visibility for the year, and Jupiter and Saturn shine until sunrise. Read on for your Skylights!

The Moon

The moon will re-join the evening sky this week – but it won’t really affect stargazing until the coming weekend. That’s because it will be only partly illuminated, and therefore not too bright, and it will set before the sky becomes truly dark, which will be around 10:30 pm local time at mid-northern latitudes. Below, I’ll mention more of the sights to see on moonless summer nights.

The old moon will be hidden from view when it rises about 40 minutes before the sun on Monday morning. At 2:32 pm EDT or 11:32 am PDT and 18:32 Greenwich Mean Time on Monday, the moon will officially reach its new moon phase. At that time our natural satellite will be located near the bright star Pollux in Gemini (the Twins), and 4.6 degrees north of the sun. While new, the moon is travelling in space between Earth and the sun. Since sunlight can only illuminate the far side of the moon, and the moon is in the same region of the sky as the sun, it becomes completely hidden from view from anywhere on Earth for about a day – unless there’s a solar eclipse, as there will be on October 14.

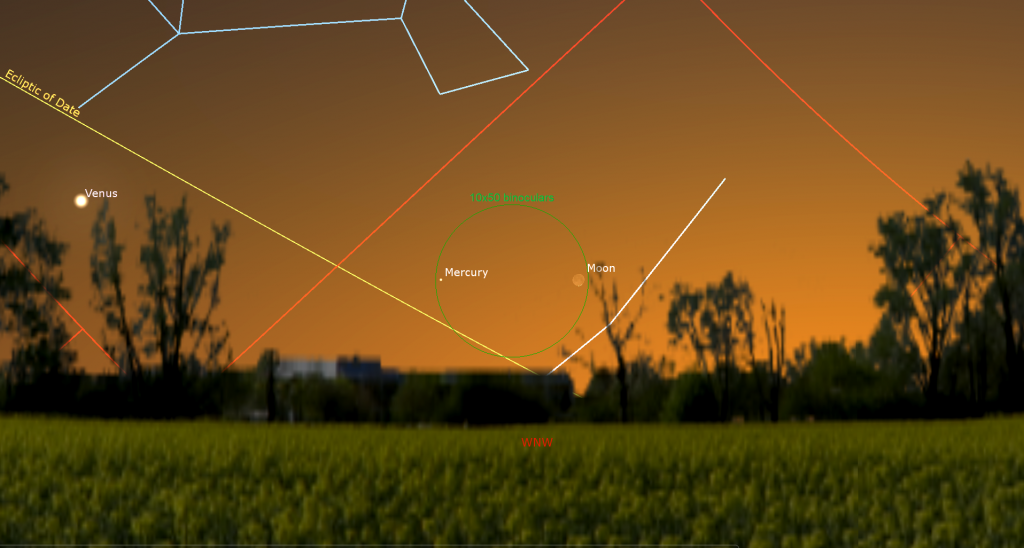

By Monday evening, the young crescent moon will be positioned above the sun at sunset, but still hidden within the bright twilight. Despite the moon being 10° farther from the sun on Tuesday, the shallow slope of the ecliptic (and moon’s orbit) will hold the moon low above the west-southwestern horizon for mid-northern latitude observers. Once the sun has completely vanished on Tuesday, you can use binoculars to search for the 1.6%-illuminated crescent moon posing less than a palm’s width to the right (or 5° to the celestial northwest) of Mercury. The best viewing time will start around 9:15 pm local time. Far brighter Venus will shine 1.5 fist diameters to the left of Mercury, so use that as the anchor point for your search. Sky-watchers at tropical latitudes will see the trio more easily – with the moon below the two planets.

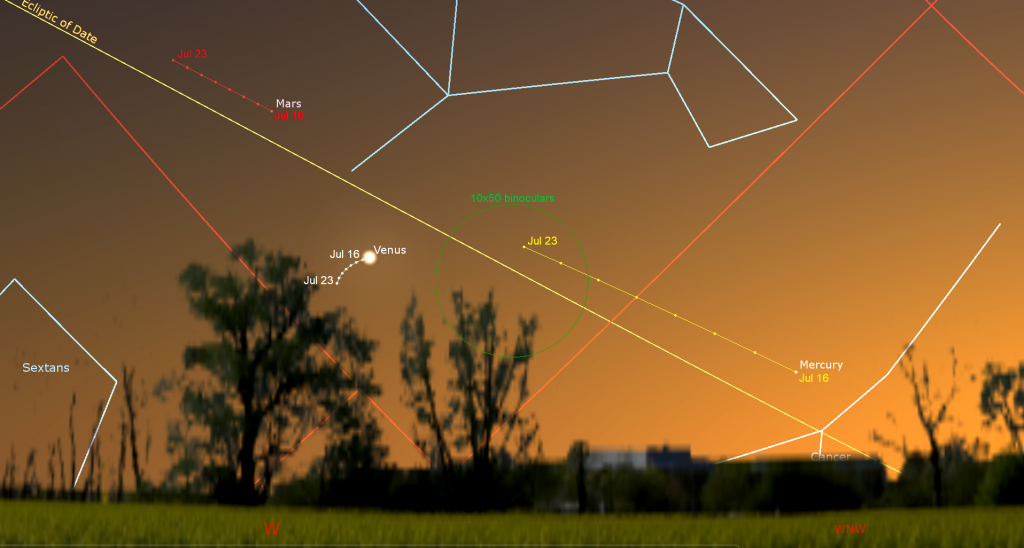

The moon will wax fuller and set later each night. On Wednesday, the young crescent moon will shine above and between Venus and Mercury. The moon will be located a fist’s diameter to the upper right of Venus and a palm’s width to the upper left of Mercury – close enough for those two to share the view in binoculars again. The reddish dot of Mars will be shining to Venus’ upper left, too – but it will be tough to spot.

The young moon’s dance with the evening planets will continue on Thursday when its pretty crescent will shine several finger widths to the upper right of the small, faint, reddish dot of Mars. The bright planet Venus will shine brightly below the moon, and fainter Mercury will be about 1.7 fist diameters to the moon’s lower right. From Thursday on, the moon will linger long enough for the sky to darken around it, revealing the stars of Leo (the Lion). Simba’s brightest star, Regulus, will sparkle near the moon and Mars.

Midweek will be a great time to watch for Earthshine on the moon, also known as the Ashen Glow and “The old moon in the new moon’s arms”. That’s sunlight reflected off Earth and back toward the moon, slightly brightening the dark portion of the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere. On Friday night the moon will continue to shine in Leo. It will spend the coming weekend beginning its trip through the lengthy form of Virgo (the Maiden). Friday will kick off the best period to view the waxing moon in binoculars and backyard telescopes. The terrain along the curved, pole-to-pole terminator boundary line will be cast into stark relief by the nearly horizontal rays of sunlight illuminating it. New features are showcased each night!

Southern Delta Aquariids Meteor Shower

The Southern Delta Aquariids meteor shower has begun. The annual event, which runs from July 12 to August 23, is caused when the Earth passes through a cloud of tiny particles dropped by a periodic comet – likely Comet 96P/Machholtz. The shower will peak overnight on Friday-Saturday, July 28-29, but is especially active for a week surrounding that date. This shower commonly generates 15-20 meteors per hour at the peak, but is best seen from the southern tropics, where the shower’s radiant, in Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), is positioned higher in the sky. Since there will be lots of moonlight around the peak, watch for fewer meteors this week, when the sky will be darker. I’ll share some meteor shower tips next week.

The Planets

As I mentioned above, the moon will be passing through a trio of planets that are gathered over the western horizon after sunset later this week. But you can seek those planets out, starting tonight (Sunday) after the sun has set.

Let’s start with Mercury as it will set first. The speedy innermost planet will be swinging farther from the sun each night, allowing it to linger after Venus and Mars depart in the coming days. Mercury will be brightening a little more each night, too. Once the sun has set, look for Mercury’s dot positioned about a palm’s width above the west-northwestern horizon. The current evening apparition will be the best one of the year for Southern Hemisphere observers, but Mercury’s position just north of a very tilted ecliptic will keep the planet very low in the sky after sunset for northerners – making this a lengthy, but poor quality showing for them. Don’t forget the slim crescent moon near Mercury on Monday-Tuesday.

Very bright Venus will emerge from the western twilight starting at sunset and then set around 10 pm. At the latitude of Toronto, you might need to stand in a spot where Venus is glimpsed between buildings or trees, but observers at tropical latitudes will see Venus more easily – higher and in a darker sky. Try to view the planet’s slim, waning crescent shape, only about 15%-full this week, as early as possible. That way Venus will be higher, shining through less intervening air, and her glare will be lessened against the bright sky surrounding her. Good binoculars should show you Venus’ non-round shape, too. The planet’s disk size will also grow a bit larger every day as it traverses the space between Earth and the sun, reducing our distance apart. The crescent moon will shine near Venus on Wednesday and Thursday.

Mars’ increasing distance from Earth has reduced its brightness substantially. Its faint, reddish speck will be hard to see in the post-sunset twilight without binoculars. Mars will be located to the upper left (or celestial east) of Venus. Leo’s bright star Regulus will shine between them. Over this week, Mars will increase its distance from Venus from a generous palm’s width tonight (Sunday) to a fat fist’s diameter next Sunday (or 7° to 11° apart). Regulus will shift into the midpoint between Mercury and Mars.

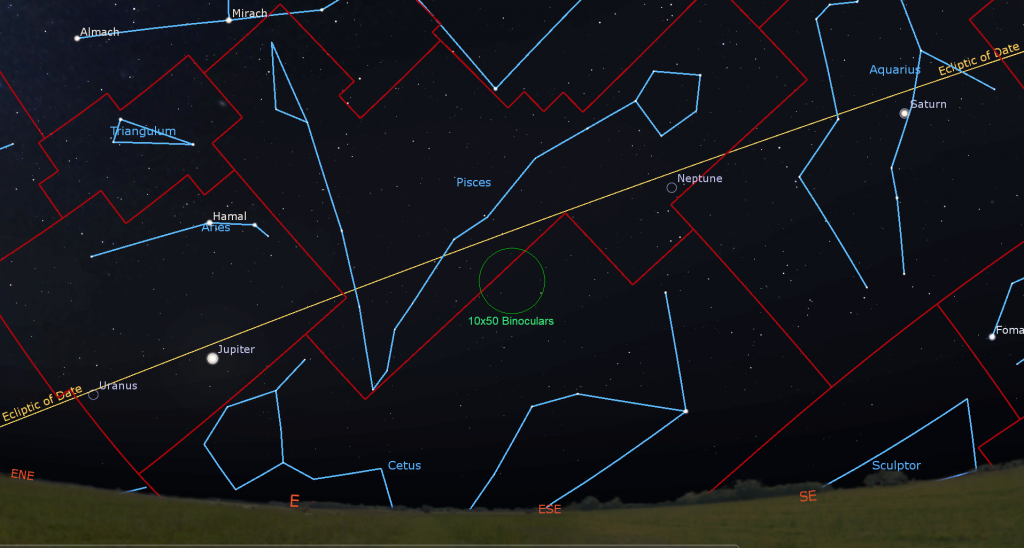

Not long after Venus sets, Saturn’s yellowish dot will rise over the eastern horizon – at about 10:40 pm local time this week. That rise time will advance by 28 minutes per week, so you’ll start catching sight of the ringed planet before bedtime by month’s end.

The best time to view Saturn in a telescope will be before dawn, when it will be located a third of the way up the southern sky. If you head outside by 4:30 am, you’ll be able to see the modest stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) around Saturn and the bright trio of the Summer Triangle stars shining off to the upper right. The very bright star Fomalhaut (or Alpha Piscis Austrini, the Southern Fish) will shine two fist diameters below Saturn during this year.

Saturn and its beautiful rings are visible in any size of telescope. If your optics are sharp and the air is steady, try to see the Cassini Division, a narrow gap between the outer and inner rings, and a faint belt of dark clouds encircling the planet. Remember to take long, lingering looks through the eyepiece – so that you can catch moments of perfect atmospheric clarity.

From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves all around the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from the far upper right (celestial west) of Saturn on Monday morning to close in on the upper left (celestial northeast) of Saturn next Sunday morning. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope? Saturn will be available for our evening viewing pleasure through its opposition in late August and then on until mid-winter! This summer the blue planet Neptune, 600 times fainter than Saturn, will be lurking two fist diameters to Saturn’s left, or 21° to its celestial northeast.

Bright, white Jupiter, which shines about 16 times brighter than Saturn, will rise at about 1 am local time this week. The brightest stars of Jupiter’s host constellation Aries (the Ram), named Hamal and Sheratan, will shine a generous fist’s diameter above the giant planet. Jupiter will be easy to see halfway up the southeastern sky until almost sunrise. Jupiter will become an evening planet by the second week of August. Then we’ll be able to view it after dinner until March, 2024.

Binoculars will show Jupiter’s four Galilean moons lined up beside the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. All four of them will huddle to the west of Jupiter next Saturday morning – but Europa will slip behind Jupiter for some of the time. From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Thursday morning, July 20, Io’s shadow will cross Jupiter with the Great Red Spot from 1:05 am to 3:04 am EDT (or 05:059 to 07:04 GMT).

Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk on Monday, Thursday, and Saturday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

Jupiter will be followed across the sky by Uranus, which will be positioned a fist’s diameter to the bright planet’s lower left (or celestial east) this summer. The magnitude 5.8, blue-green planet is visible in binoculars and small telescopes if you know where to look. It will become much easier to see in the coming weeks when it climbs higher.

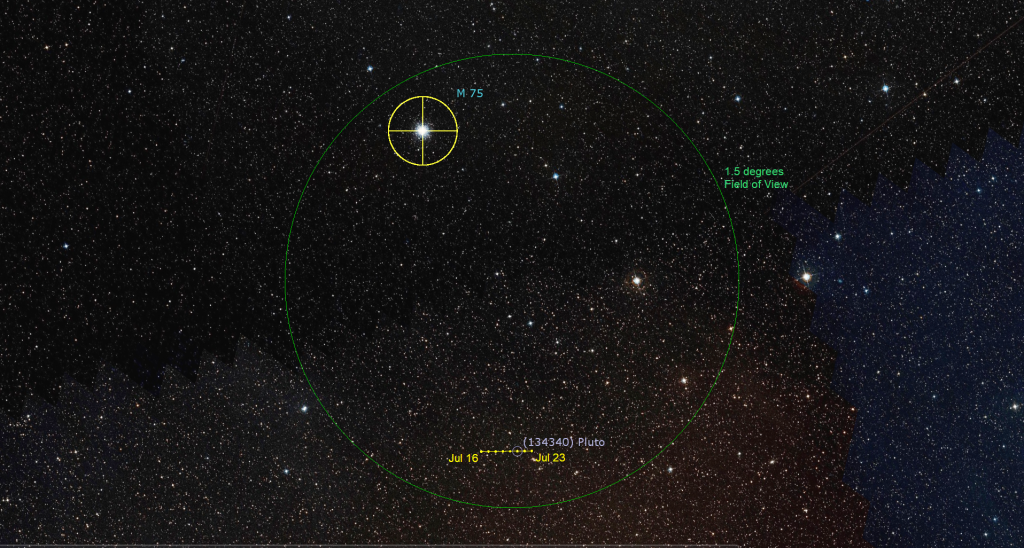

On Friday night, July 21, the dim and distant dwarf planet designated (134340) Pluto will reach opposition for 2023. On that date, the Earth will be positioned between Pluto and the sun, minimizing our distance from that outer world and maximizing Pluto’s visibility. While at opposition, Pluto will be located 5.21 billion km or 282 light-minutes from Earth. Unfortunately, it will shine with an extremely faint visual magnitude of +14.3 that is far too dim for visual observing through a small backyard telescope.

Pluto will be highest in the sky, and more readily seen, around 1:30 am local time. It will be located in the sky about 4 finger widths to the upper left (or 4.2 degrees to the celestial north-northeast) of the four medium-bright stars named Omega, 59, 60, and 62 Sagittarii, which shine well to the left (east) of Sagittarius’ Teapot-shaped asterism. Alternatively, aim your telescope a finger’s width below (or 1° to the celestial south of) the globular star cluster Messier 75. Even if you can’t see Pluto directly, you will know that it is there.

Touring the Dark Southern Sky

While the moon is out of the way, let’s grab bug spray and binoculars, or dust off the old telescope, and set up in a spot with a low and open southern horizon for a tour through the scorpion, the teapot, and the shield!

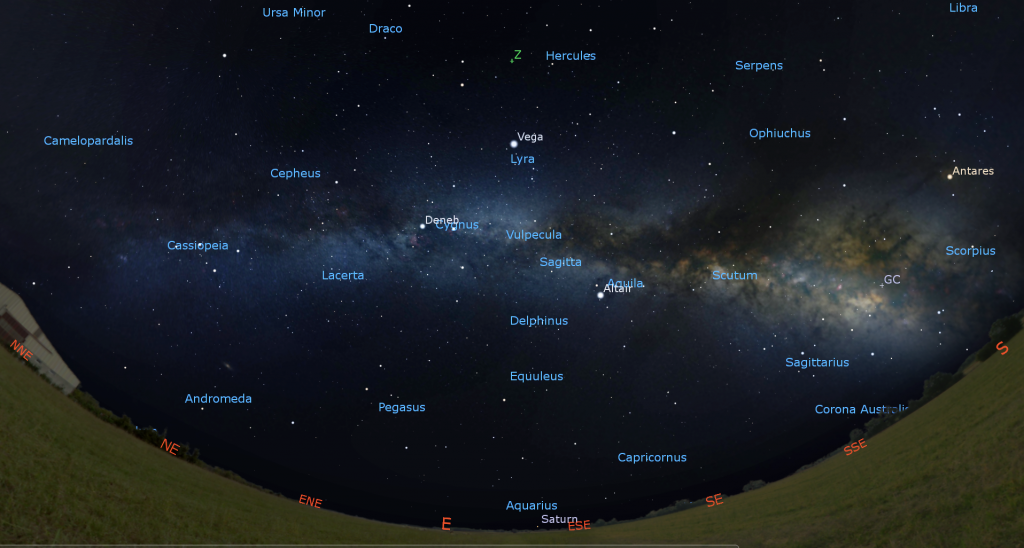

Once it’s getting nice and dark, face south and look for the Milky Way rising from the southern horizon. The brightened strip that forms the broad band of the Milky Way is the projection of our home galaxy’s disk-like plane on the night sky. It is composed of countless stars that are too far away to pick out individually by eye – but a good telescope will resolve many of them into a speckled backdrop. Humans from many cultures have long thought that this feature of the night sky resembled spilled milk. The Greeks called it galaxias, or “the milky vault”. Once humans discovered what the Milky Way glow actually was, we assigned the same word to all the other “islands of stars” in the Universe!

For mid-northern latitude observers, the Milky Way arcs overhead in the late-night summer sky. Due to haziness near the horizon, and more of Earth’s intervening atmosphere, the portion of the Milky Way higher in the sky, where it passes directly through Cygnus (the Swan), is easier to see. Around midnight local time, the great swan will be nearly overhead. The rest of the Milky Way descends to the northeast, thinning as it passes through the “W” of Cassiopeia (the Queen) and Perseus (the Hero) because that area represents the outer edge of our galaxy’s disk.

The centre of our galaxy, where lurks a supermassive black hole, is located near the place where the borders of the constellations Sagittarius (the Archer), Ophiuchus (the Serpent-Bearer), and Scorpius (the Scorpion) meet. For mid-northern latitude observers, the spot migrates to above the southern horizon only in evening from July to September. Folks in the tropics and the Southern Hemisphere see much more of our galaxy. In fact, some of the best sights in the sky are only visible from there!

Opaque interstellar dust concentrated in our galaxy’s plane obscures the stars beyond it. When you are tracing out the Milky Way on a dark, moonless night, watch for dark patches in Sagittarius and Scutum (the Shield), and long lanes of darkness that divides the way into two bands through Aquila and Cygnus.

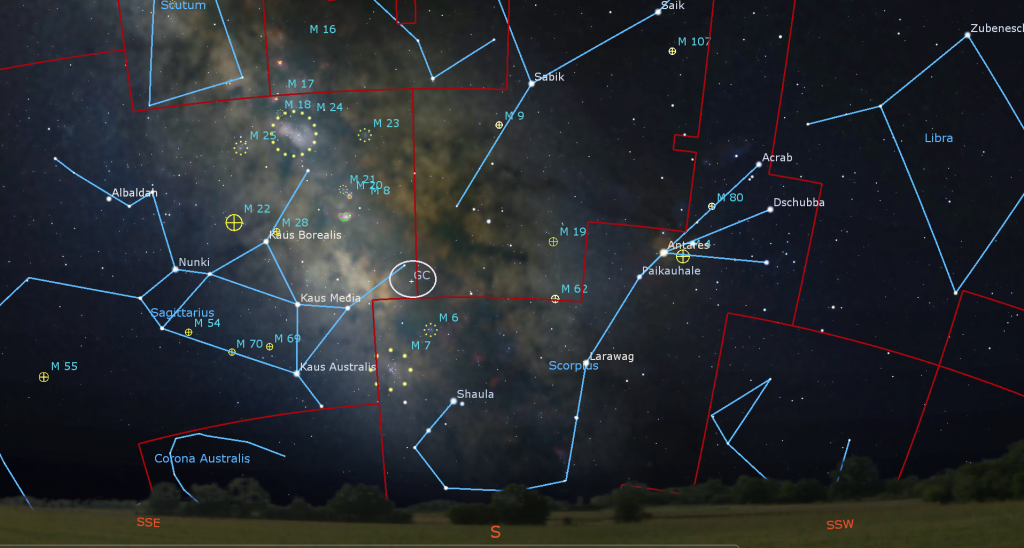

Let’s highlight some of the best sights. The distinctive constellation of Scorpius (the Scorpion) reaches its peak elevation over the southern horizon around 11 pm local time in late July. That constellation’s brightest star is orange-tinted Antares, the “Rival of Mars”. Three white, medium-bright stars aligned in a roughly vertical line to the right (or celestial west) of Antares mark the creature’s claws today – however the major stars of neighboring Libra (the Scales) used to play that role. The rest of the scorpion extends to the south, curling eastward into the Milky Way, and terminating in a bright double star named Shaula, which marks the poisonous stinger. The leftmost, easterly star, also known as Lambda Scorpii, is twice as bright as the other star, Upsilon Scorpii. Some people call them the Cat’s Eyes. Observers above mid-northern latitudes will struggle to see the southerly stars of this constellation. For Moana fans, the Maori of New Zealand consider those same stars to represent Maui’s fishhook pulling the Milky Way out of the sea every night!

For contrast with cool, reddish Antares, look at the two hot, white stars that flank the red supergiant. Magnitude 3.1 Al Niyat I (also known as Sigma Scorpii) is located 2 finger widths to the upper right (celestial northwest) of Antares. It is a B1-class star with a surface temperature of 36,200 K. The magnitude 2.8 star Tau Scorpii is located 2.25 degrees to the lower left (southeast) of Antares. Also known as Paikauhale, it is a B0-class star with a surface temperature of 30,000 K. At 734 light-years from the sun, Al Niyat I is nearly twice as far away as Tau. Use binoculars to find a fuzzy patch that is sitting just a finger’s width to Antares’ right. It is a globular star cluster named Messier 4.

Late July evenings bring us another one of the best asterisms in the sky, the Teapot in Sagittarius (the Archer). This informal star pattern features a flat bottom formed by the stars Ascella on the left and Kaus Australis on the right, a triangular pointed spout pointing right, marked by the star Alnasl, and a pointed lid marked by the star Kaus Borealis. The stars Nunki and Tau Sagittarii form its handle. The asterism is low in the sky, but it reaches maximum height above the southern horizon around midnight local time, when it will look as if it’s serving its hot beverage – with the steam rising as the Milky Way. By the way – the centre of our galaxy is located just 4.5 finger widths to the upper right of Alnasl!

Next, use your binoculars to explore the rich star fields and nebulae sprinkled along the Milky Way above Sagittarius. The bright star clusters known as Ptolemy’s Cluster (also designated Messier 7), the Sagittarius Star Cloud (Messier 24), and Messier 25 will appear as compact, bright, white clouds in binoculars. You can also look for the bright knots of nebulosity comprising the Lagoon Nebula (Messier 8), the Omega / Swan Nebula (Messier 17), and the Eagle Nebula (Messier 16). Higher up, you’ll discover more good clusters, including Messier 39 and Messier 29 in Cygnus, Caldwell 16 in Lacerta (the Lizard), the Wild Duck Cluster (Messier 11) and Messier 26 in Scutum (the Shield). Use your backyard telescope for a closer look at them!

Scutum (the Shield) was created by Johannes Hevelius in 1683 by stealing some of the stars from next-door Aquila (the Eagle). The small constellation (84th out of 88, by area) occupies some prime celestial real estate along the summertime Milky Way. Scutum, which reaches its highest position over the southern horizon at midnight local time in late July, has a background of rich star fields, which are overlain by some fine open star clusters, including the aforementioned Wild Duck Cluster. Use binoculars to trace out the dim stars that form the constellation and then follow up with your telescope.

Hercules on High

If you missed my tour of the constellation of Hercules (the Hero), which will still be a good target this week, I posted it here.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

Eastern GTA sky watchers are invited to join the RASC Toronto Centre and Durham Skies for solar observing and stargazing at the edge of Lake Ontario in Millennium Square in Pickering on Friday evening, July 21, from 7 pm to midnight. Details are here. Before heading out, check the RASCTC home page for a Go/No-Go call – in case it’s too cloudy to observe.

This summer, spend an afternoon in the other dome at the David Dunlap Observatory! On Saturday afternoon, July 22, visitors 6 years old and up can join me in my Starlab Digital Planetarium for an interactive journey through the Universe at DDO. We’ll tour the night sky and see close-up views of galaxies, nebulas, and star clusters, view our Solar System’s planets and alien exo-planets, land on the moon, Mars – or the Sun, travel home to Earth from the edge of the Universe, hear indigenous starlore, and watch immersive fulldome movies! Ask me your burning questions, and see the answers in a planetarium setting – or sit back and soak it all in. Please note that all guests will sit on a clean floor. A registered adult must accompany all registered participants under the age of 16. We run a session at 1 pm and another at 2:30 pm. More information and the registration links are here.

On the first clear weeknight from July 24-28 the public are invited to Binoculars Stargazing on the lawn at the David Dunlap Observatory. Arrive for this free program at sunset. You’ll learn to use star charts and basic observing techniques, then use your binoculars to follow a guided tour through the night sky by RASC Toronto Centre astronomers, and stay after the tour to practice your new skills. Please wear / bring appropriate supplies for being outside. Note that there is no building or washroom access during this program. All participants under the age of 16 must be accompanied by an adult. As this program is weather dependent, please visit RASC Toronto’s home page or Facebook page for a GO or NO-GO call.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcast with RASC National returns on Tuesday, August 1 at 3:30 pm EST. We’ll focus on an interesting topic in astronomy. Then we’ll highlight our next batch of RASC Finest NGC objects. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!