The Equinox Begins Spring, Venus Gleams in Evening, and Some Dark Sky Faves Before the Junior Moon Joins Planets!

The beautiful Rosette Nebula in Monoceros consists of a circular patch of glowing hydrogen gas and an internal star cluster, created as the hydrogen gas collapsed. Stan Noble tool this image, which was featured as the SkyNews picture of the week for November 3, 2017, in Aneroid, Saskatchewan. The image spans about two finger widths of sky, left-to-right. More of Stan’s beautiful images can be enjoyed at https://www.astrobin.com/users/stannoble/

Hello, Spring Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of March 19th, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

Spring in the Northern Hemisphere will arrive on Monday. The moon will return to shine as a young crescent in the western sky later this week, where it will meet with Jupiter, Venus, and Uranus. Until then, the moonless nights will be ideal for viewing late winter and early spring’s finest sky objects. Read on for your Skylights!

Happy March Equinox!

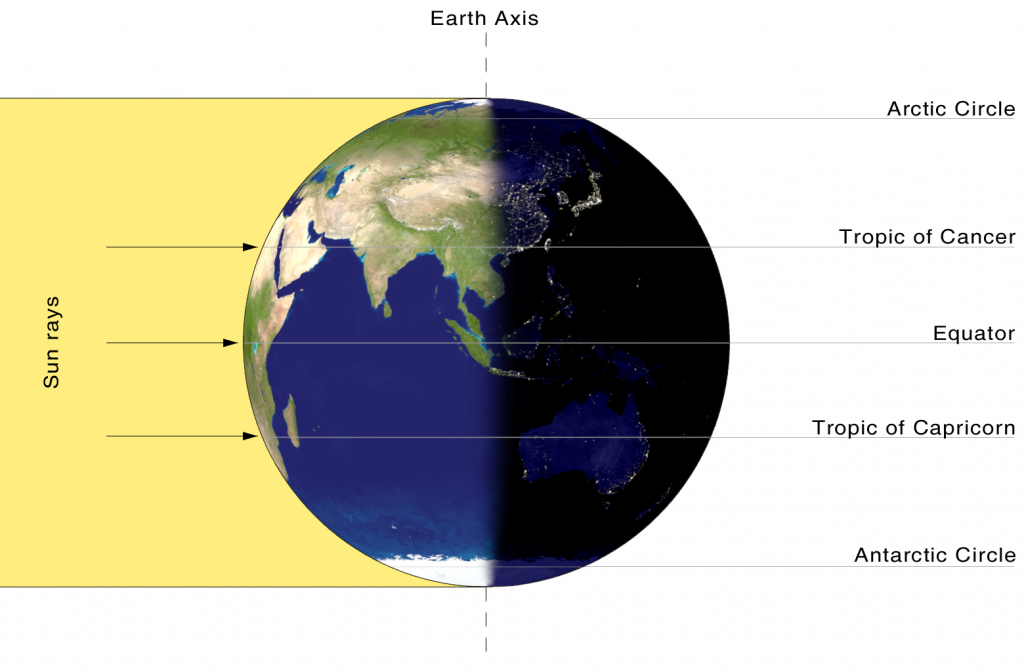

On Monday, March 20 at 5:24 pm EDT, 1:24 pm PDT, or 21:24 Greenwich Mean Time, spring will officially arrive in the Northern Hemisphere! At that moment, the sun’s apparent motion eastward along the ecliptic will carry it cross the celestial equator and into the northern sky. (Of course, the sun isn’t moving – Earth is!) The astronomical term for this event is the Vernal Equinox, where “vernal” is Latin for “spring”. I prefer to say March Equinox because autumn will commence for everyone in the Southern Hemisphere on that same day. The hemispheres will trade autumn for spring again at the September or Autumnal Equinox.

On each of the two equinoxes, the world experiences about 12 hours each of daylight and darkness. This is where the word equinox (Latin for “equal night”) comes from. The actual date with 12 hours of day and night, known as the equilux, varies according to latitude. In the zone encompassing southern Canada and the northern USA states, that occurs on March 17 in 2023. The day-night balance varies by latitude and doesn’t quite hold true at the poles where you could climb a ladder and see the sun. Moreover, the amount of daylight is always a few minutes longer than night because the disk of the sun takes 2 minutes to rise or set at the equator and even longer at higher latitudes where the ecliptic is tilted. In other words we’ve already started to see the sun when its centre crosses the horizon rising, and we still see the upper half of the sun for a while after its centre sets.

The March Equinox produces several interesting effects. For the following six months, the sun will spend more than 50% of each 24-hour period shining overhead of the lucky folks in North America, Europe, and Asia! More time with the sun above the horizon means warmer air and longer daylight hours! At the same time, folks in the Southern hemisphere have to accept shorter, colder days and longer nights. (Warmly dressed astronomers don’t mind long winter nights!)

The amount of daylight increases fastest around the equinox. With the sun setting about 1.2 minutes later every night and rising about 1.8 minutes earlier every morning, each subsequent day brings three more minutes of daylight. Conversely, the amount of daylight decreases by about three minutes per day around September 20. The day/night balance changes extremely slowly around the winter and summer solstices in later December and June, respectively.

The period around the equinoxes also offer increased odds of seeing the aurorae at both high northern and southern latitudes. Just as two bar magnets lined up with their poles in the same direction repel one another strongly, the Earth’s magnetic field repels the sun’s field. At the equinoxes, the Earth’s axial tilt is orthogonal to the Earth-sun line, so the two “magnets” aren’t as parallel, reducing Earth’s ability to repel the sun’s field and the charged particles that trigger aurorae in our upper atmosphere. A few years ago I wrote a more detailed post on this topic with diagrams here.

It seems highly likely that St. Patrick’s Day, now observed annually on March 17, arose after the early Christian Catholic church converted pre-existing Celtic celebrations already being observed at the equinox to a church feast day. It drifted away from the typical equinox date because of inaccuracies in the Julian calendar.

Persians will celebrate their New Year, called Nowruz or Norooz “New Day” on Monday, March 20, 2023. It begins at the midnight hour occurring closest to the March equinox, as measured in Iran Standard time. In 2023, spring in Iran begins on March 21 at 1 am, an hour after midnight on March 20. The Persian calendar, which originated with the Babylonians, is based on the sun, but not the moon. I discussed this and other connections between world religions and astronomy during an Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy session on YouTube here.

The Moon meets Planets

For everyone on Earth, the moon will begin this week hidden beside the glare of the sun before sunrise on Monday morning. It’ll officially reach its new moon phase at 1:23 pm EDT, 10:23 am PDT or 17:23 Greenwich Mean Time on Tuesday, at which time it will be located in western Pisces (the Fishes), approximately 3.5 degrees south of the sun.

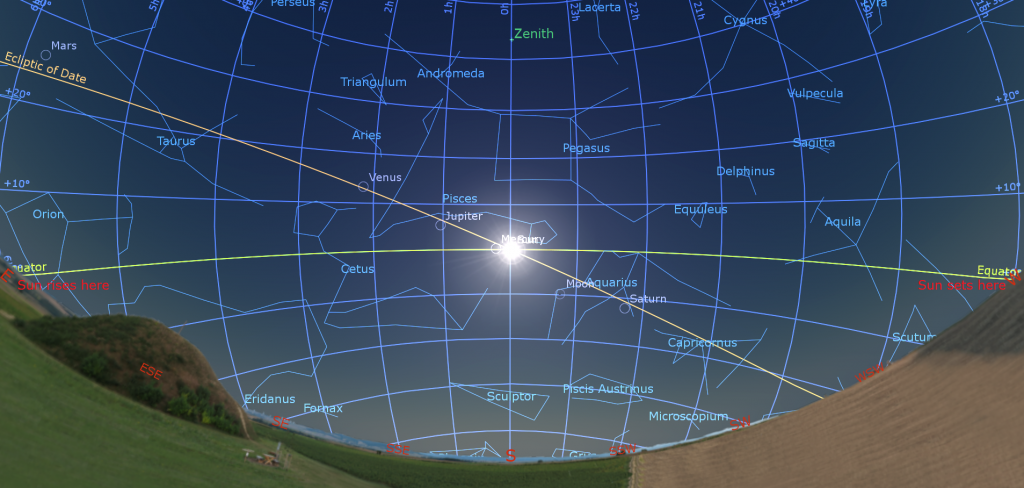

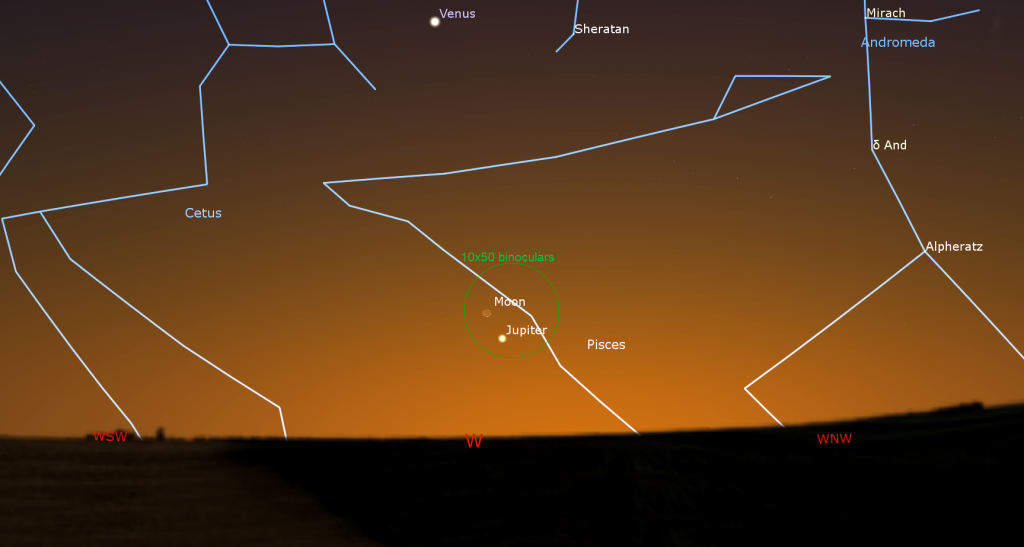

Technically, the young moon will be visible in the western sky after sunset on Wednesday – but its razor thin, 2%-illuminated crescent will be swimming in a bath of evening twilight, making it very hard to spot without a very clear western horizon. It will also be positioned just a finger’s width to the upper left (or 1.2° to the celestial east) of Jupiter’s bright dot – close enough for them to share the view in binoculars or a backyard telescope (only after the sun has completely set, please). The pair will set about 70 minutes after the sun does. As the sky darkens, Jupiter will become obvious, aiding in your search. Observers located in northeastern South America can see the moon pass in front of (or occult) Jupiter in a twilit sky starting around 22:18 GMT. The rest of northern South America, southern Central America, and parts of the Pacific Ocean can observe that event in bright daylight, though the moon will be very hard to locate and dangerously close to the sun.

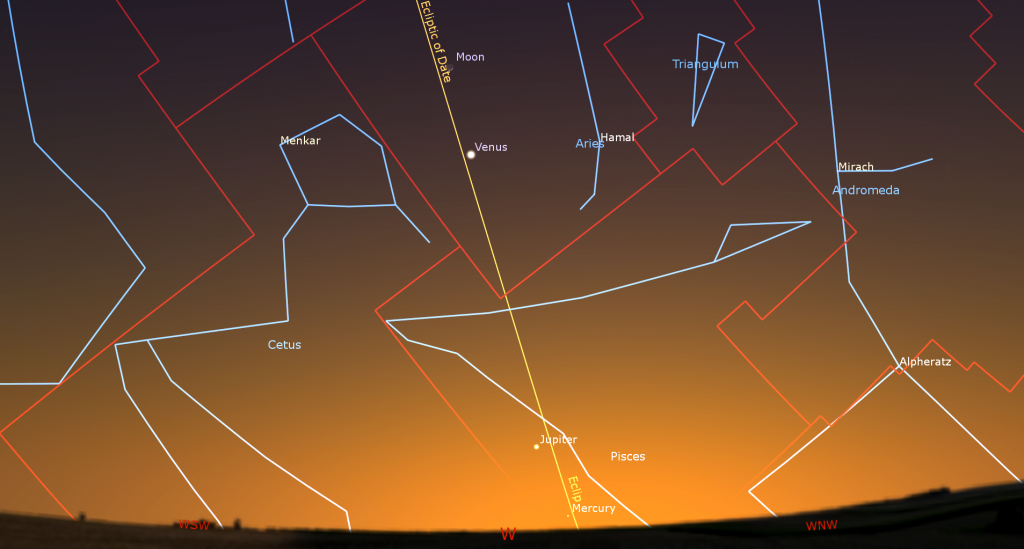

On Thursday evening, the very slender crescent of the young moon will resemble the Cheshire Cat’s smile when it shines below Venus and above Jupiter – setting up a wonderful widefield photo opportunity in the western sky after sunset. Watch for Earthshine on the moon. Sometimes called the Ashen Glow or the Old Moon in the New Moon’s Arms, the phenomenon is visible within a day or two of new moon, when sunlight reflected off Earth and back toward the moon slightly brightens the unlit portion of the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere. Observers located along a zone stretching across southern and eastern Africa, Madagascar, the southeastern Arabian Peninsula, India, Pakistan, and the southern half of Asia can see the moon occult Venus during mid-day on Friday. Those located from Thailand to the Philippines will see that occultation in a darker sky on Friday evening. Use an app like Stellarium to find out your local circumstances.

On Friday night, the waxing crescent moon’s eastward orbital motion will lift it to shine a palm’s width above Venus. Both objects will be in Aries (the Ram). If you have a clear view to the horizon, you might be able to spot Mercury peeking over the western horizon less than a palm’s width below (or 5.6° to the celestial west of) Jupiter. The alignment of Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, and the moon will nicely trace out the plane of our Solar System. Their line will be nearly vertical because the ecliptic is orthogonal to the western horizon on evenings surrounding the equinox.

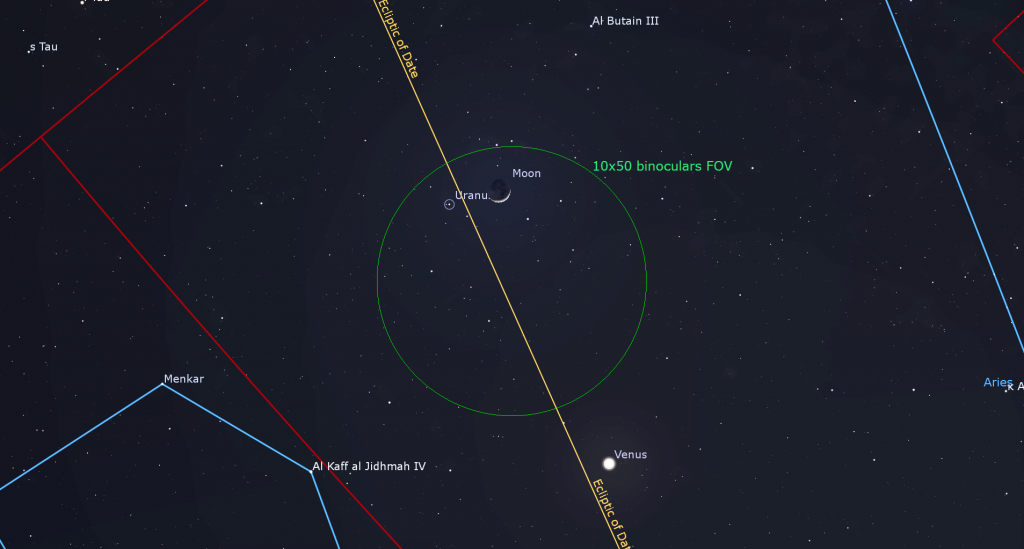

For viewers in the eastern parts of the Americas, the magnitude 5.8 planet Uranus will also be positioned less than two lunar diameters to the left (or celestial SSE) of the moon, allowing skywatchers to see the blue-green planet’s dot in binoculars and backyard telescopes. Observers west of the Eastern Time Zone will see the moon an increasing distance above Uranus.

Another pretty binoculars treat will arrive on Saturday night. Once the sky darkens, the bright little cluster of stars named the Pleiades, the Seven Sisters, and Messier 45 will sparkle about two finger widths to the upper right (or 2.5 degrees to the celestial north) of the waxing crescent moon. By the time they set around midnight, the moon will have shifted to the left of the cluster. To better see the cluster’s stars, hide the moon beyond the edge of your binoculars’ field of view. Large aperture telescopes and long exposure photos can reveal faint blue nebulosity surrounding the cluster’s brighter stars. In Greek mythology, those stars are named for the daughters of Atlas and Pleione. The stars representing the parents shine together at the upper left (eastern) edge of the cluster. The Pacific Islanders know M45 as Matariki. The indigenous groups of North America call it Bagone-giizhig, the Hole in the Sky.

The moon will spend a second night in Taurus (the Bull) on Sunday night, when it will shine between the Pleiades and reddish Mars.

The Planets

This could be your final week to see Jupiter in the evening sky, where it’s been shining brightly since it first began to rise before midnight back in mid-July. Earth’s orbital motion will put Jupiter in conjunction with the sun on April 11 and then it will join Saturn in the eastern pre-dawn sky around the end of May. The giant planet won’t officially return to the evening sky again until early August.

For now, Jupiter will appear in the lower part of the western twilit sky after sunset and set by about 9 pm local time. Once the sun has fully disappeared, you can safely use binoculars or a telescope to seek out Jupiter’s four Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. On Friday in the Americas three moons will be grouped to the upper (eastern) side of Jupiter, with Callisto tucked closely beside the planet’s southern pole. Look closely for it!

Toward the end of this week, speedy Mercury will start to become visible just above the western horizon right after sunset. It will approach and then pass Jupiter on the coming weekend.

The bright planet Venus will be the “star” of the show during evening for quite some time to come. Its separation above (east of) Jupiter will continue to increase each night as its angle from the sun grows. That is also allowing the magnitude -3.97 planet to gleam in a dark sky for a while before it sets at about 10:30 pm in your local time zone. Viewed in a telescope this week, Venus will display an 80%-illuminated disk that is slowly waning each night. To see Venus’ rugby ball shape most clearly in a telescope, view the planet as soon as you can locate it through your optics, when it will be higher and shining through less intervening air. Again – take care to avoid aiming a telescope or binoculars near the sun. As I described in the previous section, the young moon will hop past Venus on Thursday-Friday.

Venus’ eastward orbital motion is also carrying the planet towards far fainter Uranus. At mid-week the blue-green planet will be located about a fist’s diameter above (or 9° to the celestial east-northeast of) Venus. Uranus’ magnitude 5.8 dot will sit a generous fist’s width to the upper left (or 13° to the celestial southeast) of Hamal, the brightest star in Aries (the Ram). The medium-bright stars Pi Arietis and Sigma Arietis, which are similar in brightness to Uranus, will be above and below the blue-green planet in the same binoculars field of view. The best time for telescope-viewing of Uranus is right after dusk, when the planet will be located one third of the way up the west-southwestern sky. It will be too low for crisp views after 9:30 pm. Don’t forget that the crescent moon will have a close encounter with Uranus on Friday night.

Mars’ own eastward trek is helping it to delay its inevitable drop into the sunset, but it continues to fade in brightness and become smaller in telescopes as Earth increases its distance from the red planet. After dusk, Mars will appear in eastern Taurus (the Bull), about two-thirds of the way up the southwestern sky. That will be its absolute best telescope viewing time. Its still-prominent reddish dot will form a red triangle above and between the bright, reddish star Aldebaran, which marks the angry eye of the bull, and ruddy Betelgeuse at Orion’s shoulder. Already fainter than Betelgeuse, Mars will fade to match Aldebaran’s intensity around mid-week. In the meantime you can watch Mars marching eastward, farther from Aldebaran and towards the toe stars of Gemini (the Twins). The planet will set during the wee hours of the night.

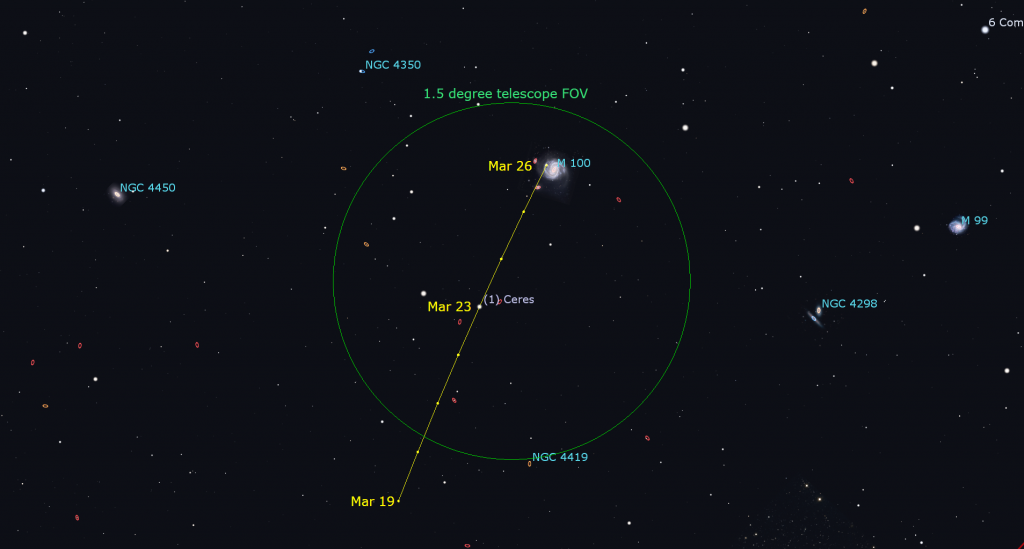

During March, the largest object in the main asteroid belt, a minor planet named (1) Ceres, will perform a westerly retrograde loop that carries it through the northern edge of the Virgo Cluster of Galaxies. That region of the sky, located about midway between the bright stars Denebola in Leo (the Lion) and Vindemiatrix in Virgo (the Maiden), contains thousands of galaxies, including quite a few larger ones that are visible in backyard telescopes under a dark sky.

In the early hours of Tuesday, Ceres will reach opposition, its closest approach to Earth for the year – a distance of 239.2 million km or 13.3 light-minutes. On the nights around opposition, this largest resident of the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter will shine with a peak visual magnitude of 7.0, which is well within reach of binoculars and backyard telescopes. That night it will be located in southwestern Coma Berenices (Berenice’s Hair) about midway between the stars Beta Comae Berenices and Zavijava (or Beta Virginis). Ceres will ascend the eastern sky after dusk, and then reach its highest elevation, and peak visibility when due south at 1:30 am local time.

Also starting on Tuesday, Ceres will approach close enough to a grand design spiral galaxy named Messier 100 (or the Blow-dryer Galaxy or NGC 4321) for them to share the eyepiece in a backyard telescope. Ceres will creep closer to the galaxy every night and brush the northern edge of the bright spiral’s arms on Sunday evening, March 26. Ceres will take about 9 hours to cross the galaxy’s disk. The team at Virtual Telescope Project plans to broadcast a live view of Ceres crossing the galaxy. Details are here. Ceres and M100 will remain cozy enough to view together until March 29. The early-setting crescent moon should allow the galaxy and the asteroid to be visible in full-sized binoculars from a dark sky location in late evening, when they’ll be high in the southern sky.

Over the coming weeks Saturn will gradually return to visibility in the east before sunrise.

Stargazing Sights for Mid-March

With the moon missing from the evening sky until later this week, it’s a fine time to explore the wonders of the dark sky in binoculars and backyard telescopes.

Once the sky darkens this week, head outside and look almost halfway up the northwestern sky for the distinctive W-shaped constellation of Cassiopeia (the Queen) dangling from her highest star Segin. A palm’s width to the left of Segin you will find the Double Cluster. These two open star clusters, each 0.3 degrees across and almost a finger’s width (0.45°) apart, form a spectacular sight in binoculars or a telescope at low magnification. They cover twice the width of the full moon. The lower, more westerly cluster, also known as NGC 869 is more compact, and contains more than 200 white and blue-white stars. NGC 884, the higher, easterly cluster, is slightly more spread out. The clusters reside in the Perseus Arm of the Milky Way and are located about 7,000 light-years from our sun. Their region of the sky is heavily loaded with opaque interstellar dust that has extinguished their intensity.

The constellation of Auriga (the Charioteer) is high in the western sky during March evenings. Below its very bright star Capella, nick-named the Goat Star, look for a triangle of smaller stars known as “the Kids”. From the Kids you can continue to trace out an oval of stars measuring 1 by 1.7 fist diameters shining to the left (or celestial south) of Capella. The outer rim of our Milky Way passes through Auriga – filling the lower left (or southern) half of the oval with star clusters and nebulas. Several of them are very obvious if you scan the constellation with binoculars from a dark location. I’ll post a star chart showing them here.

Search midway between Auriga’s stars Hassaleh (Iota Aurigae) and Mahasim (Theta Aurigae) for a large triangle of bright open star clusters. Messier 38 will appear directly between those bright stars. It’s large in size, and shows a loose scattering of stars, hence its nickname the Starfish Cluster. Another cluster named NGC 1893 will be three finger widths to its lower right. Its nickname is the Letter Y Cluster because of the pattern its stars form. The Pinwheel Cluster or Messier 36 will be positioned a thumb’s width inside the ring, midway between the stars Mahasim and Elnath. It is nicely concentrated, with stars arranged in curved chains. The Salt and Pepper Cluster or Messier 37, which will sit opposite to the pinwheel, but on the outside of the ring, is composed of a very dense collection of stars. Aim your telescope two finger widths to the lower right of the Kids to find the Kite Cluster or NGC 1664. It’s not very bright, but it’s very pretty! At the same distance from the Kids, but inside Auriga’s ring you’ll find the large, loose cluster named NGC 1778.

The faint stars of the constellation of Monoceros (the Unicorn) occupies the southern sky to the left (celestial east) of Orion (the Hunter), between the bright stars Procyon and Sirius. Often overlooked, this constellation straddles the winter Milky Way. Among its many treasures are the spectacular Rosette Nebula (or NGC 2237) and its internal star cluster NGC 2244. The Rosette Nebula is more than double the size of the moon, so it shows very well in binoculars. Search a slim palm’s width above the Rosette Nebula for the Christmas Tree Cluster. The area around and below the cluster hosts a large triangle of faint nebulosity named NGC 2264, adding to the Christmas tree appearance. It’s upside-down in binoculars and right-way-up in a telescope. The Double Wedge Cluster (or NGC 2232) and the spectacular triple star Beta Monocerotis sit a fist’s diameter to the upper right (or 10° to the celestial north) of much brighter Sirius.

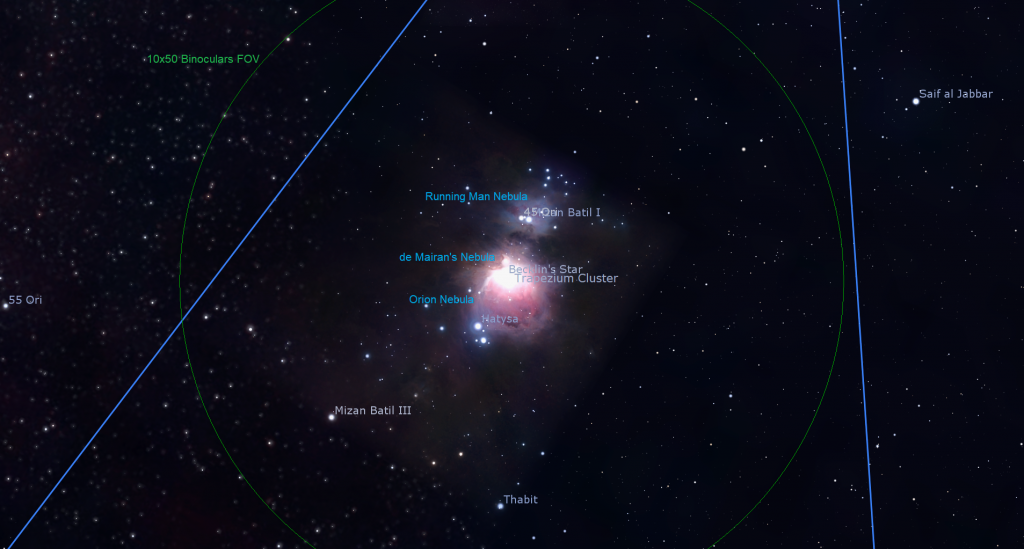

The Sword of Orion hangs below Orion, the Hunter’s three-starred belt, which is easy to spot about halfway up the southwestern sky after dusk this week. On the sky the sword measures a finger’s width wide by a thumb’s width high (or 1.5 by 1 degrees). The patch of light in the middle of the sword is the spectacular and bright nebula known as Messier 42, M42, and the Orion Nebula. Even binoculars will reveal the fuzzy nature of this object. De Mairan’s Nebula or Messier 43, a section of the same interstellar gas cloud lies just above (to the north of) M42. It has been separated from the main gas cloud by a lane of dark dust in the foreground. Medium-to-large backyard telescopes will reveal a complex pattern of veil-like gas and dark dust lanes that form M42 and M43. The nebula, and the stars forming within it, are approximately 1,350 light-years from our sun and fill a volume of space measuring 24 light-years across.

Buried in the core of the Orion Nebula is a tight clump of stars collectively designated Theta Orionis (Orionis is Latin for “of Orion”), but better known as the Trapezium – because the brightest four stars occupy the corners of a trapezoid shape. Even a small telescope should be able to pick out this four-star asterism – but good seeing conditions and a larger aperture telescope will reveal two additional faint stars in the trapezium. The trapezium stars are hot, young O- and B-type stars that are emitting intense amounts of ultraviolet radiation. The radiation causes the Hydrogen gas they are embedded within to shine brightly as red light. At the same time, some of their light is scattered by surrounding dust, producing blue light. The combination of red and blue is why there is so much purple and pink in colour images of the nebula.

To the unaided eye, a patch of brightness just below the Orion Nebula defines the southern tip of Orion’s sword. The area is dominated by the bright, magnitude 2.75 star named Nair al Saif “the Bright One of the Sword”. It also goes by Hatysa, Iota Orionis, and the nick-name “The Lost Jewel of Orion”. The star is expected to explode in a supernova one day. It, too is surrounded by faint nebulosity. Astronomers believe that this star was gravitationally kicked out of the Hyades Cluster in Taurus (the Bull) about 2.5 million years ago.

Just a short distance below (or 8 arc-minutes to the celestial southwest of) Nair al Saif, you’ll find a pair of medium-bright, magnitude 4 stars designated HIP26199 and HIP26197. This duo is almost 3,000 light-years from the sun and they shine with an intense blue light indicative of their extreme surface temperatures. Astronomers estimate that each of those two stars is approximately 40,000 times more luminous than our sun. The entire area is surrounded by faint nebulosity. If you have an O-III or nebula filter, use it to enhance the view in your telescope.

Leo Guides Us to Galaxies

If you missed last week’s tour of the spring constellation of Leo (the Lion) and the galaxies he hosts, I posted it here along with some photographs of the galaxies I mentioned.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras (weather permitting), answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. On Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Wednesday evening, March 22 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will live stream their monthly Speakers Night meeting. This month will Parisa Nozari, MSc Candidate at Queen’s University, Canada. Her talk is titled From Dust Grains to Stars and Shots in the Dark – about star formation and dust production in galaxies. Everyone is invited to watch the presentation live on the RASC Toronto Centre YouTube channel. Details are here.

RASC’s has resumed Public sessions at the David Dunlap Observatory – but they are still offering several online programs from home. The modest fee supports RASC’s education and public outreach efforts at DDO. Only one registration per household is required. Prior to the start of the program, registrants will be emailed the virtual program link.

On Sunday afternoon, March 26 from 12:30 to 1 pm EDT, tune in for DDO Sunday Sungazing. Safely observe the sun with RASC, from the comfort of your home! During these family-friendly sessions, a DDO Astronomer will answer your questions about our closest star: the sun! Learn how the sun works and how it affects our home planet. Live-streamed views of the sun through small telescopes will be included, weather permitting. Only one registration per household is required. Deadline to register for this program is Wednesday, March 22, 2023 at 3 pm. More information is here and the registration link is here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcast with RASC National returns on Tuesday, March 28 at 3:30 pm EST. We’ll talk about a fascinating topic in astronomy. Then we’ll wrap up by highlighting our first batch of spring RASC Finest NGC objects. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!