The Equinox Brings Spring, the Crescent Moon Passes Pre-dawn Planets while morning Mars Meets Jupiter, and Dark Sky Delights!

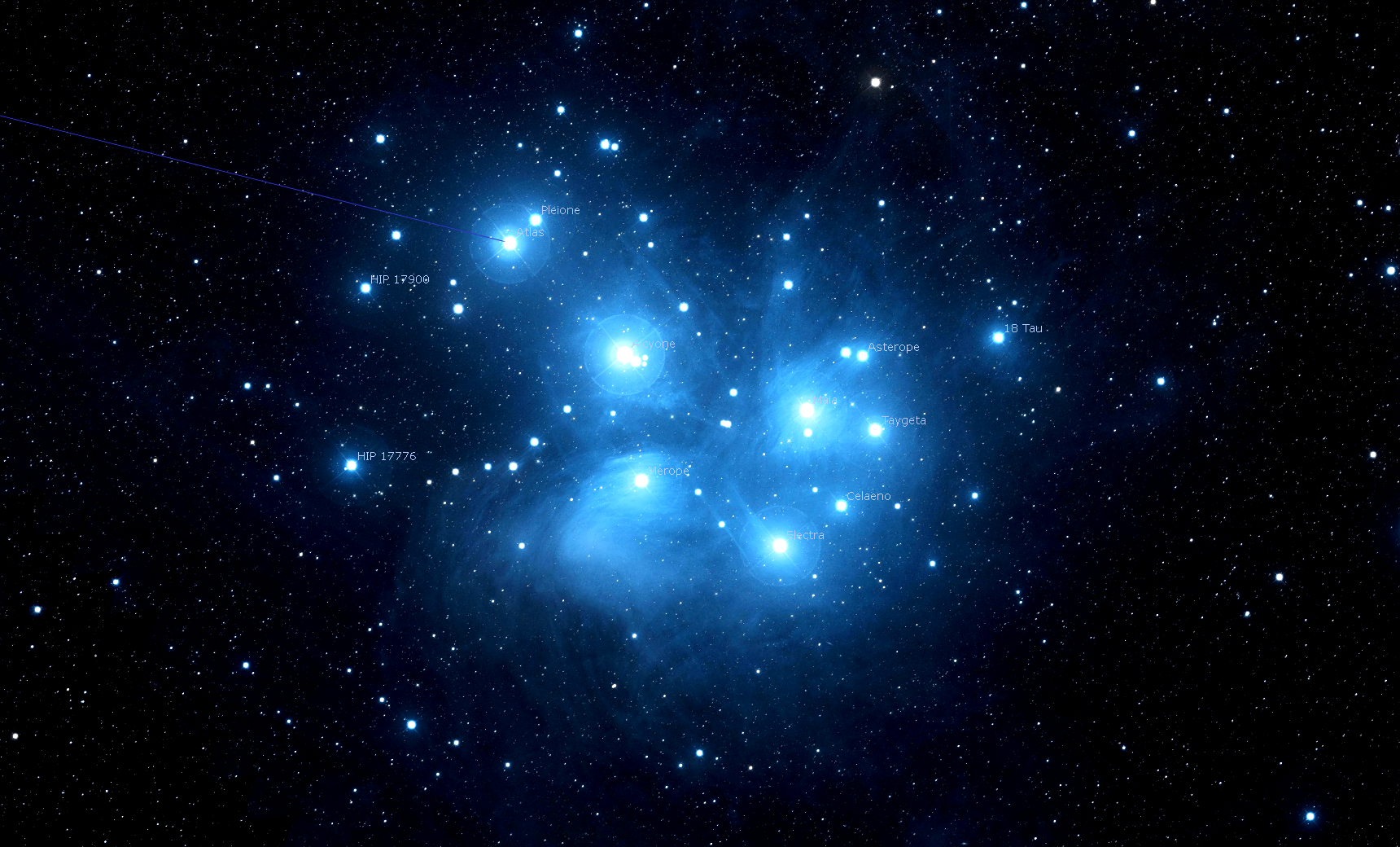

The bright and large open star cluster known as the Pleiades or Messier 45 is composed of sibling stars (the daughters of Atlas and Pleione in Greek mythology) that formed of the same gas cloud. Interstellar dust in the foreground scatters the stars’ light with a blue colour. The cluster is very easily seen with unaided eyes and binoculars, even under city skies. It sits well to the upper right of Orion.

Happy Spring, Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of March 15th, 2020 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To receive Skylights by email, please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe together!

At the Vernal Equinox on Thursday, spring will commence for the Northern Hemisphere – and daylight hours will be increasing at their fastest rate. The moon will spend the week in the pre-dawn sky, leaving the evenings dark for stargazers the world over (although bright Venus will light up the western sky after dusk). That waning morning moon will tour the four bright planets gathered in the pre-dawn southeast, joining Mars as it passes close to Jupiter. Mercury will be there, too. Here are your Skylights!

Happy Vernal Equinox!

At 10:50 pm Eastern Daylight Time on Thursday, March 20 (or 03:50 Greenwich Mean Time on Friday), spring will officially arrive in the Northern Hemisphere. The astronomical term for the event is the Vernal Equinox. But March Equinox is a more appropriate term because “vernal” means spring, and spring won’t arrive in the Southern Hemisphere until September! Let’s look at the equinox and spring from an astronomical perspective.

The Celestial Equator is an imaginary circle around the sky that sits directly above the Earth’s equator. It divides the sky into two equal bowls – the Northern and Southern celestial hemispheres. The stars in the sky are all fixed in place, and fall into one bowl or the other.

As Earth orbits around the sun in the course of a year, we observe that the sun travels eastward in front of the distant stars, tracing out another circle on the sky called the Ecliptic. The limited set of constellations that straddle the Ecliptic form the zodiac. That apparent motion of the sun causes new stars to appear each season, and the same stars to shine every year on the same date.

Due to the 23.5° tilt of the Earth’s axis of rotation, the Celestial Equator and the Ecliptic are tipped that amount with respect to each other. The circles intersect at two spots in the sky. Astronomers call them nodes. One node located near the western fish’s head in Pisces, and the other is half the sky away from that in western Virgo (the Maiden). Think of the circles as two hula hoops with the same centre, Earth. Thousands of years ago, those crossing points were located in Aries (the Ram) and Libra (the Scales), but the slow wobble (or precession) of the Earth’s axis migrates those positions along the Ecliptic over long time scales. Coined long ago, the terms First Point of Aries and Cusp of Aries are sometimes used to denote the March crossing point. You might see a ram’s horn symbol marked there on diagrams of Earth’s orbit.

The sun’s eastward motion along the ecliptic is about one degree per day, and twice per year the sun encounters a node. The March Equinox occurs at the precise moment that the sun “steps over” the Celestial Equator in Pisces, carrying the sun into the northern half of the sky. Six months later, on the Autumnal or September Equinox, the sun will again cross the Celestial Equator in Virgo and enter the southern half of the sky. The date of the equinoxes varies a bit due to the same phenomenon that gives us leap years – the extra quarter day in our year.

The March Equinox produces several interesting effects. For the next six months, the sun will spend the majority of each day in our northern hemisphere sky, overhead of the lucky folks in North America, Europe, and Asia! More time above the horizon for the sun means warmer air and longer daylight hours! At the same time, folks in the Southern hemisphere have to accept shorter, colder days and longer nights. (Warmly dressed astronomers don’t mind long winter nights!) On each equinox, we experience about 12 hours each of daylight and darkness (it varies by latitude). This is where the word equinox (Latin for equal night) comes from.

The amount of daylight added every day is at a maximum on the equinox. With the sun setting about 1.5 minutes later every night and rising about 1.5 minutes earlier every morning, each day has three more minutes of daylight than the day before. Conversely, the amount of daylight decreases by about three minutes per day around September 20. The lengths of the day and night periods barely change at the winter and summer solstices in December and June, respectively.

The times around the equinoxes also offer better chances to see the aurorae at high northern and southern latitudes. Just as two bar magnets lined up with their poles in the same direction repel one another strongly, the Earth’s magnetic field repels the sun’s field. At the equinoxes, the Earth’s axis is tilted neither towards nor away from the sun, so the two “magnets” aren’t as parallel, reducing Earth’s ability to repel the sun’s field and the charged particles that trigger aurorae in our upper atmosphere.

Evening Zodiacal light

For about half an hour after dusk between now and the new moon on March 24, look west-southwest for a broad wedge of faint light rising from the horizon and centered on the ecliptic below Venus, where the dim stars of Pisces (the Fishes) are. This is the zodiacal light – reflected sunlight from interplanetary particles of matter concentrated in the plane of the solar system. Try to observe it from a location without light pollution, and don’t confuse the zodiacal light with the brighter Milky Way, which extends upwards from the northwestern evening horizon at this time of year. Averted vision might help you see the dim light.

Observers in the Southern Hemisphere can see the zodiacal light in the eastern pre-dawn sky starting around March 23. Venus’ brightness will hamper our ability to see the evening zodiacal light this year, but the phenomenon will re-occur next year around this time, when Venus won’t be there.

The Moon and Planets

The moon will nearly complete its monthly trip around the Earth this week. As it does so, it will swing towards the sun in the pre-dawn sky, leaving evenings worldwide nice and dark for spring stargazing. On Monday morning, the waning half-illuminated moon will rise in the east at about 2 am in your local time zone. It will be sitting a palm’s width to the upper left (or 6° to the celestial north) of Antares, the brightest star in Scorpius (the Scorpion). The moon’s last quarter phase will officially occur at 5:34 am EDT on Monday. Around last quarter, the moon rises so late that it remains visible in the southern sky during the morning daylight.

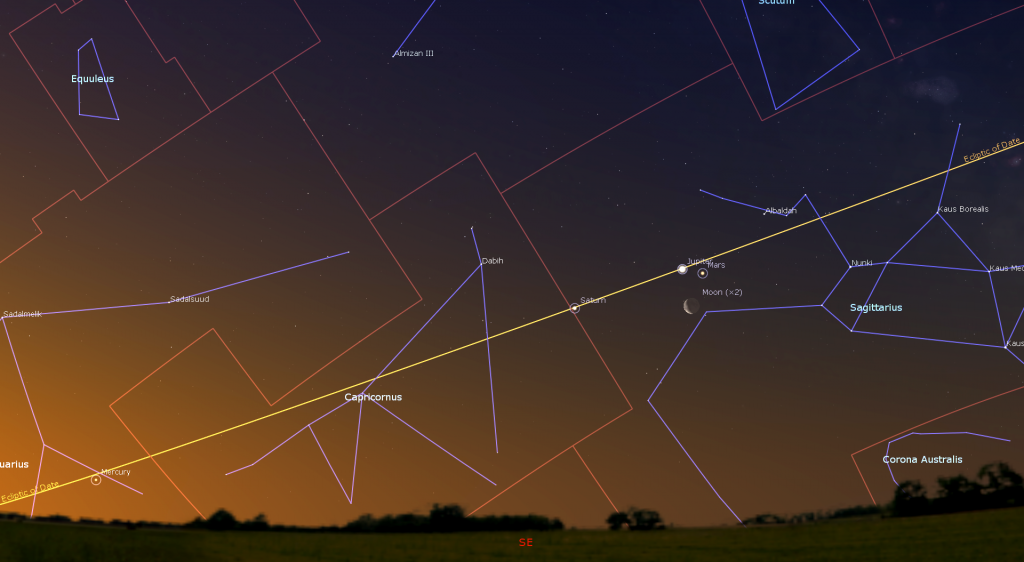

Mid-week mornings will feature spectacular sights in the southeastern sky before sunrise. On Tuesday morning, the pretty, waning crescent moon will sit above the teapot-shaped constellation of Sagittarius (the Archer), and only a fist’s diameter to the upper right (or celestial west) of the three bright planets Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn gathered there.

Before sunrise on Wednesday, the waning crescent moon will take up a position less than two finger widths below (or 1.5 degrees to the celestial south of) Mars and Jupiter. The moon and the two planets will easily fit into the field of view of binoculars and will make a lovely widefield photograph when composed with nearby Saturn and some interesting foreground terrain. Hours earlier, from approximately 6:40 to 7:40 GMT, observers in southern South America, South Georgia, Antarctica, and the Kerguelen Islands will see the moon pass over (i.e., occult) Mars.

On Thursday morning, the moon’s slim crescent will land a palm’s width to the lower left (or 6 degrees to the celestial southeast) of Saturn. Observers from Europe and Africa to Asia will see the moon sitting much closer to Saturn. Thursday’s scene will make another fantastic photograph.

Completing its monthly pass through the morning planets, look very low in the east-southeastern sky before sunrise on Saturday to see the delicate crescent of the old moon sitting a palm’s width to the lower right (or 6 degrees to the celestial southwest) of Mercury. The optimal viewing time for the duo will occur between about 6:45 and 7 am local time. That will be your last glimpse of the moon before it passes its new phase and joins the western evening sky next week. (For eye safety, if you use binoculars to find Mercury, be sure to put them away before the sun begins to rise.)

Extremely bright Venus will dominate the western evening sky for weeks to come. Our sister planet will pop out of the twilight sky well before dusk, and then set prior to midnight in your local time zone. Venus is still climbing higher and still brightening! Right now, Venus’ magnitude value is -4.41. It will reach maximum brightness of -4.73 on April 28. That’s a 35% brightness increase from now! (Magnitude values use a logarithmic scale. The more negative the magnitude value, the brighter an object looks.)

If you want to see Venus’ less-than-fully-illuminated disk, aim your telescope at the planet as soon as you can pick it out of the darkening sky. In a twilit sky, Venus’ out-of-round shape will be more apparent. And, when Venus is higher in the sky you’ll be viewing the planet more clearly – through less of Earth’s distorting atmosphere. The dim, blue-green planet Uranus will be located a generous palm’s width below Venus this week.

The month of March is giving early risers all around the world some planetary delights in the southeastern pre-dawn sky! That’s where Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and Mercury are strung out in a chain along the ecliptic. If you have an open view of the southeastern horizon, the three outer planets will be very easy to see with your unaided eyes every morning. Mercury will be there, too – but much lower and closer to the sun, and therefore tough to spot.

The fun begins after about 4:30 am in your local time zone. That’s when reddish Mars will rise. Much brighter, and whiter, Jupiter will follow it minutes later. And medium-bright, yellowish Saturn will join them half an hour after that, at about 5 am. The three outer planets will be nicely visible against a dark sky until about 7 am. After that, Mars and Saturn will fade from view, but Jupiter will remain visible until sunrise. By the way, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot will be in view on Wednesday morning, March 18 and on Friday morning, March 20.

On Monday morning, all three planets will sit within a fist’s diameter (about ten degrees) of one another. Jupiter will be in the middle, but much closer to Mars. While Jupiter and Saturn maintain their separation of 7 degrees, Mars’ faster eastward motion will carry it towards Jupiter until Friday. On Friday morning, Mars and Jupiter will be separated by only 42 arc-minutes (the moon’s apparent diameter is 30 arc-minutes). In fact, from Thursday to Saturday, Mars and Jupiter with its four moons, will appear together in the field of view of a backyard telescope. After Friday, Mars will head toward a similar encounter with Saturn two weeks later.

Speedy little Mercury will rise over the east-southern horizon at about 6:30 am local time this week. It will not climb very high in the sky during this appearance. The best viewing times fall between 6:45 am and 7 am local time, but observers who live closer to the equator will have better luck seeing it.

Stargazing Sights for Mid-March

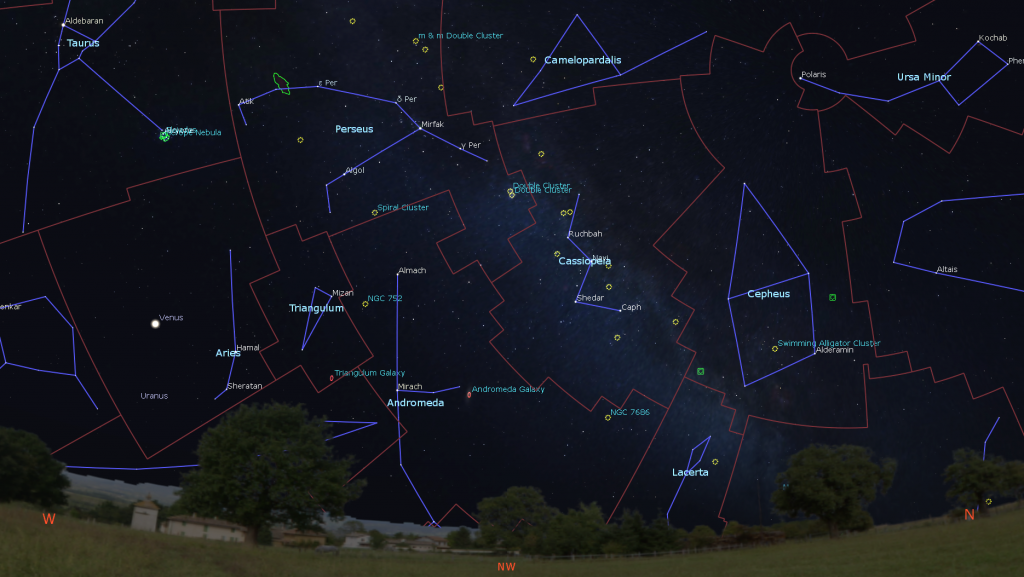

With the moon vacating the evening sky, this week will be ideal for exploring the wonders of the dark sky in binoculars and backyard telescopes. Remember that I took you through a tour of Orion (the Hunter) here and Canis Major (the Big Dog) here.

Once the sky becomes dark on a clear evening, head outside and look halfway up the northwestern sky for the distinctive W-shaped constellation of Cassiopeia (the Queen). A palm’s width to her upper left you will find the Double Cluster. These two open star clusters, each 0.3 degrees across and approximately 0.45 degrees apart, form a spectacular one degree-wide sight in binoculars or a telescope at low magnification. (That’s twice the width of the full moon.) The lower, more westerly cluster, also known as NGC 869 is more compact, and contains more than 200 white and blue-white stars. NGC 884, the higher, easterly cluster, is slightly more spread out. The clusters reside in the Perseus Arm of the Milky Way and are located about 7,000 light-years from our sun. Their region of the sky is heavily loaded with opaque interstellar dust that extinguishes their intensity.

The constellation of Auriga (the Charioteer) is high in the western sky during March evenings. The outer rim of our Milky Way galaxy passes directly through Auriga, so the constellation is rich in open star clusters that are visible with unaided eyes from dark sky locations. Binoculars and telescopes will readily show them in moderately light-polluted skies. The western (lower) region of Auriga contains the clusters NGC1664, NGC1778, and NGC1857. Bright Messier 38 (NGC1912), the nearby dimmer NGC1907, bright Messier 36 (NGC 1960), and NGC1893 are towards the centre of Auriga’s ring of stars. The bright open cluster called Messier 37 (NGC 2099) sits along the ring’s upper left side. Another cluster named NGC2281 is a fist’s diameter above the ring. How many of these patches of stars can you see?

The Pleiades open star cluster, also known as the Seven Sisters and Messier 45 is located in the western sky above Venus. Visually, the cluster is made up of young, hot blue stars with the names Asterope (“as-ter-OH-pea”), Merope, Electra, Maia, Taygeta, Celaeno, and Alcyone. They are indeed related – born of the same primordial gas cloud. In Greek mythology, they were the daughters of Atlas, and half sisters of the Hyades. To the unaided eye, only six of the sister stars are usually seen; their parents, the stars Atlas and Pleione, are huddled together at the east end of the grouping. Under magnification, hundreds of stars appear with them. Not surprisingly, many cultures, including Aztec, Maori, Sioux, Hindu, and more, have noted this object and developed stories around it – usually interpreting it as a hole in the sky or the portal to the afterlife. In Japan, it is called Suburu, and forms the logo of the eponymous car maker. Due to its shape, some people mistake the Pleiades for the Little Dipper.

During mid-evenings in mid-March annually, the modest constellation of Monoceros (the Unicorn) occupies the southern sky to the left (celestial east) of Orion, between the bright stars Procyon and Sirius. Often overlooked, this constellation straddles the winter Milky Way. Among its many treasures are the spectacular Rosette Nebula and the star cluster (NGC2244 and 2238) that sits inside it, the Christmas Tree Cluster and its associated nebulosity (NGC2264), the Double Wedge Cluster (NGC2232), and the spectacular triple star Beta Monoceros, which sits a fist’s diameter to the upper right (or 10° to the celestial north) of much brighter Sirius.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Out of an abundance of caution over the COVID-19 virus, public star parties and lectures have been cancelled until early April.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!