The Morning Moon Meets Scorpius, Evening Venus Sparkles above Jupiter, and a Look at Leo and Some Spring Galaxies!

The relatively bright galaxy named NGC 2903 sits in front of Leo, the Lion’s nose, just below the reddish star Alterf. The magnitude 9 spiral galaxy is visible in medium-sized telescope under dark sky conditions. End-to-end the galaxy spans 11 arc-minutes, or one-third of the full moon’s diameter! While it didn’t make Charles Messier’s List, it is certainly on mine!

Hello, mid-March Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of March 12th, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The moon will be rising in the hours after midnight this week and then lingering into morning daylight. Early in the week it will spend some time visiting the scorpion. In evening Venus will rise and Uranus and Jupiter sink sunward, while fading Mars shines on high. Ceres will travel near some Virgo cluster galaxies, and I highlight the best sights of Leo. Read on for your Skylights!

Saving Daylight?

Did you turn your clocks back an hour last night? I wrote about Daylight Saving Time (or DST, for short), last week here.

As Earth is now only one week away from the March equinox, the hours of daylight at mid-northern latitudes are increasing at their maximum rate of 3 minutes per day. Luckily for astronomers, 2 minutes of that change goes to the earlier sunrises, so evening stargazing will only be delayed by about 9 minutes over this week.

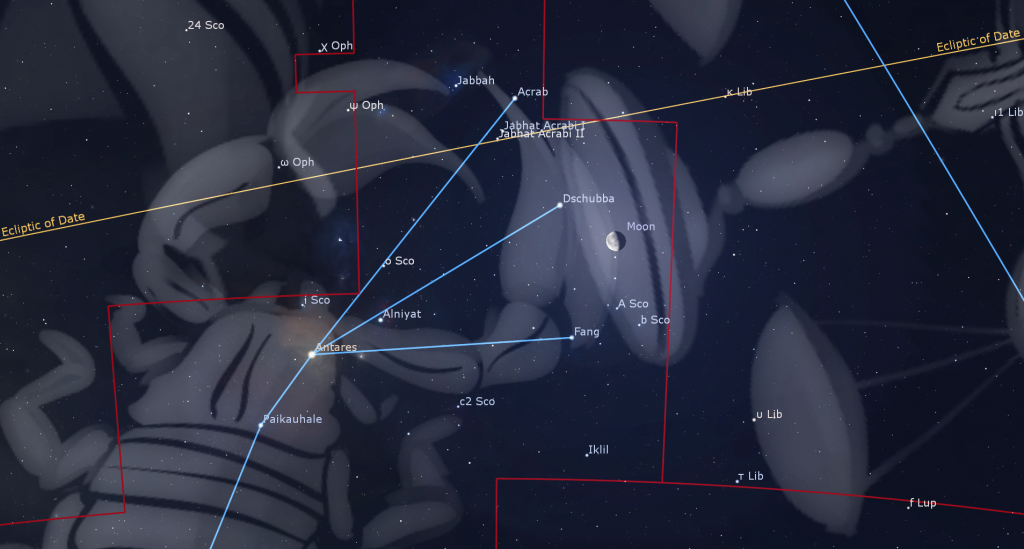

The Morning Moon meets Scorpius

If you want to see the moon this week, you’ll need to look towards the lower part of the southern sky when you head to school or work in the morning. For most of this week its pale form will haunt the sky like the Ghost of Evenings Past after sunrise. Early risers can see the moon in dark sky until Friday. After that it will be swimming in the morning twilight. Astronomers look forward to this week of the year because spring evenings are loaded with large, but faint galaxies that don’t show well in moonlight.

On Monday morning, the slightly gibbous moon will rise around 1 am in your local time zone. Once it clears the treetops, it will shine in western Scorpius near the gently curving row of small white stars that form the scorpion’s claws. The moon and those stars will climb highest, due south, around 6 am – before the sky begins to brighten. By then the claw stars will be oriented up-down. From top to bottom, they are Jabbah or Nu Scorpii, Acrab or Beta Scorpii, Dschubba or Delta Scorpii, Fang or Pi Scorpii, and Iklil or Rho Scorpii. Jabbah and Iklil are noticeably fainter than the other three. All of the claw stars are about 500 light-years away from our sun. A backyard telescope at high magnification will reveal that Jabbah, Acrab, and Dschubba are close-together double stars. Sharp eyes and binoculars will show a widely spaced pair of stars named Jabhat Acrabi I and II or Omega 1,2 Scorpii shining just below Acrab.

On Tuesday morning, the easterly orbital motion of the moon will cause its half-illuminated form to shine several finger widths to the left (or less than 4.5 degrees to the celestial east of the bright, orange-tinted star Antares, the heart of the Scorpion. That will be just close enough for them to share the view in binoculars until sunrise. Skywatchers in more easterly time zones will see the moon somewhat closer to Antares. That red giant star is located 600 light-years away from our sun. Scorpius (the Scorpion) will be there every morning this spring, with the moon visiting it monthly.

The moon will reach its third quarter phase at 10:08 pm EDT or 7:08 pm PDT on Tuesday. It won’t be above the horizon in the Americas because moon phases occur independently of Earth’s rotation. That time translates to Wednesday at 02:08 Greenwich Mean Time. If that’s before sunrise in your part of the world, look up to see the moon exactly half-illuminated on its western side, towards the pre-dawn Sun.

On Wednesday morning the waning crescent moon, slightly less than half-full, will shine near the spout of the teapot-shaped stars of Sagittarius (the Archer). The moon will be shining very close to the centre of our Milky Way galaxy. Thursday morning will see the moon inside the teapot’s handle.

On Friday the moon won’t clear the rooftops towards the southeast until the sky is brightening – but its crescent will be a pretty sight. Take a picture! If you have a clear horizon on Saturday morning, you might spot the even slimmer crescent moon positioned low in the southeast before sunrise. If you do find the moon, look for the pale dot of Saturn shining nearly two fist diameters to the moon’s lower left (celestial northeast). Observers at more southerly latitudes will have an easier view of them. The moon will hop to sit a palm’s width to Saturn’s lower right on Sunday, but its very slim crescent will be very hard to spot so close to sunrise. Always turn optics away from the eastern horizon before the sun rises.

The Planets

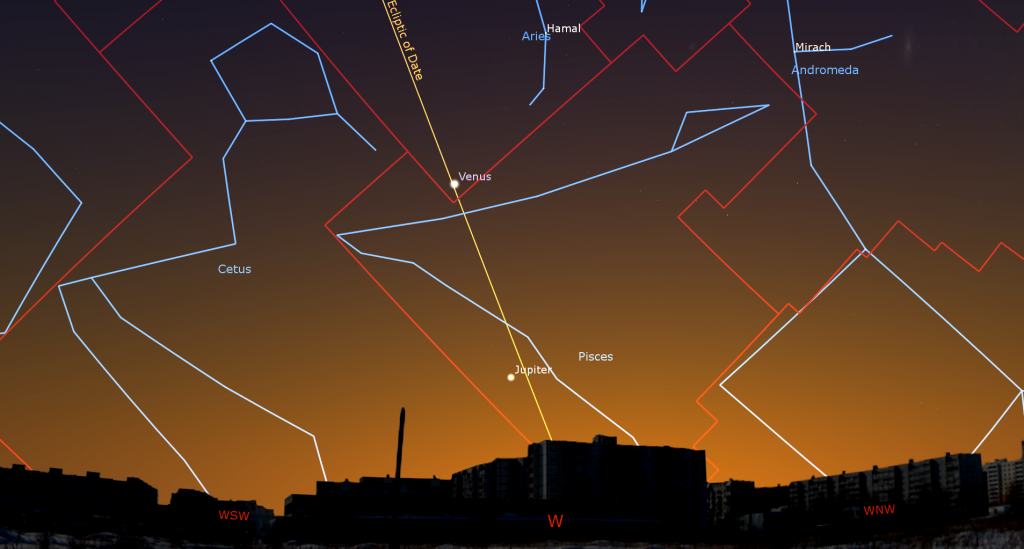

The western sky after sunset this week will host dazzling Venus gleaming above bright Jupiter. The two planets will continue to separate in the coming weeks. Tonight (Sunday) they’ll be a fist’s diameter (10.7°) apart. Next Sunday night Jupiter will be almost twice as far from five times brighter Venus. This is happening because three planets are in motion around the sun. Venus’ orbital motion is carrying it about 1° (a finger’s width) farther from the sun every five days. At the same time Jupiter and the background constellations are migrating downwards towards the sun due to the Earth’s orbital motion. Our changing perspective moves the stars west by 4 minutes each day – or half an hour per week. That’s why the constellations are replaced each season. Jupiter is also creeping eastward in its orbit, in the same direction as Venus, but it’s so far away from us that it effectively behaves like the distant stars around it.

The daily descent of Jupiter is also ending our clear views of that planet and reducing Jupiter’s lustre as we see it through an increasing thickness of Earth’s blanket of air. Since you’ll be able to see Venus pop out of the bright twilit sky first, you can use it to locate Jupiter while it’s still high enough in the sky for binoculars and a backyard telescope to show Jupiter’s Galilean moons named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. The moons will all be grouped to the lower (western) side of Jupiter on Tuesday evening and three moons will be on the higher (eastern) side on Friday. (Europa will be crossing Jupiter’s disk then.) Check them daily! Jupiter will set around 9 pm in your local time zone.

Venus increasing angle from the sun will allow the planet to shine in a dark sky for a while each night and then set at about 10:20 pm local time. The “Evening Star” will be with us until well into summer. Viewed in a telescope this week, Venus will display a slowly waning, 82%-illuminated disk that is only about 40% the size of Jupiter. To see Venus’ rugby ball shape most clearly in a telescope, look at the planet as soon as you can see it through your optics, when it will be higher and shining through less intervening air. Take care to avoid aiming near the sun.

Uranus will continue to share the early evening sky with Venus. This week the blue-green planet will be located about 1.6 fist diameters above (or 16° to the celestial east-northeast of) Venus. Their separation will diminish a little every night because of Venus’ motion. Uranus’ magnitude 5.8 dot will sit a generous fist’s width to the upper left (or 13° to the celestial southeast) of Hamal, the brightest star in Aries (the Ram). The medium-bright stars Pi Arietis and Sigma Arietis, which are similar in brightness to Uranus, will flank the blue-green planet in the same binoculars field of view. The best time for telescope-viewing of Uranus is right after dusk, when the planet will be located a third of the way up the west-southwestern sky. It will be too low for crisp views after 9:30 pm.

Mars continues to shine through most of the night, but it continues to fade in brightness and become smaller in telescopes as Earth increases its distance from the red planet. Mars will be descending from its highest point (and its absolute best telescope viewing time) right after dusk. Look for its still-prominent reddish dot perched high in the southwestern sky between the horns of Taurus (the Bull). It will be positioned above and between the bright, reddish star Aldebaran, which marks the angry eye of the bull, and ruddy Betelgeuse at Orion’s shoulder. Already fainter than Betelgeuse, Mars will fade below Aldebaran’s intensity next week. In the meantime you can watch Mars marching eastward, farther from Aldebaran and towards the toe stars of Gemini (the Twins). The planet will set during the wee hours of the night.

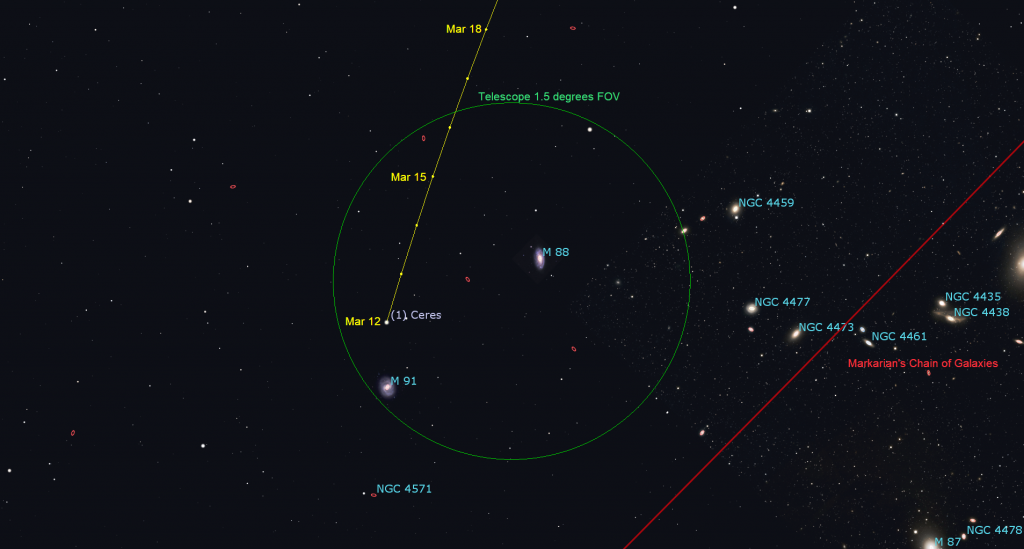

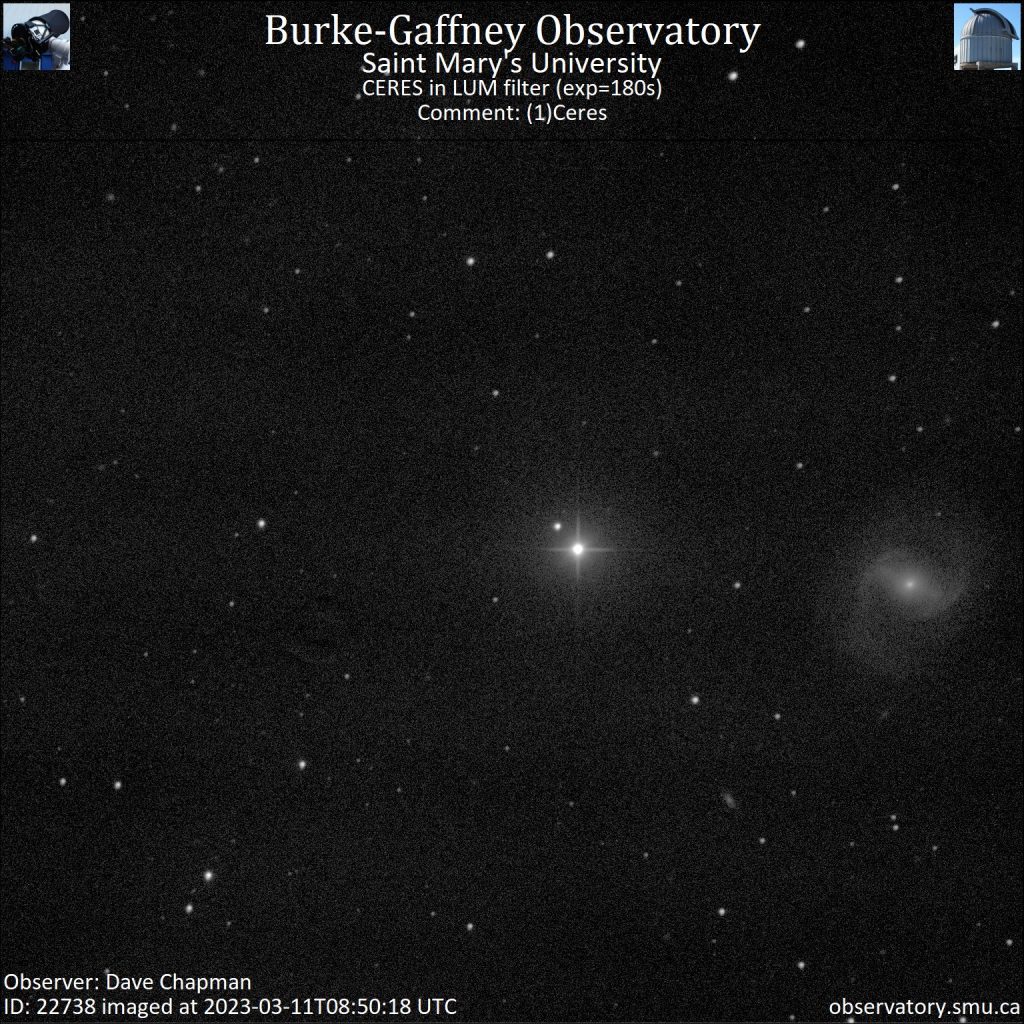

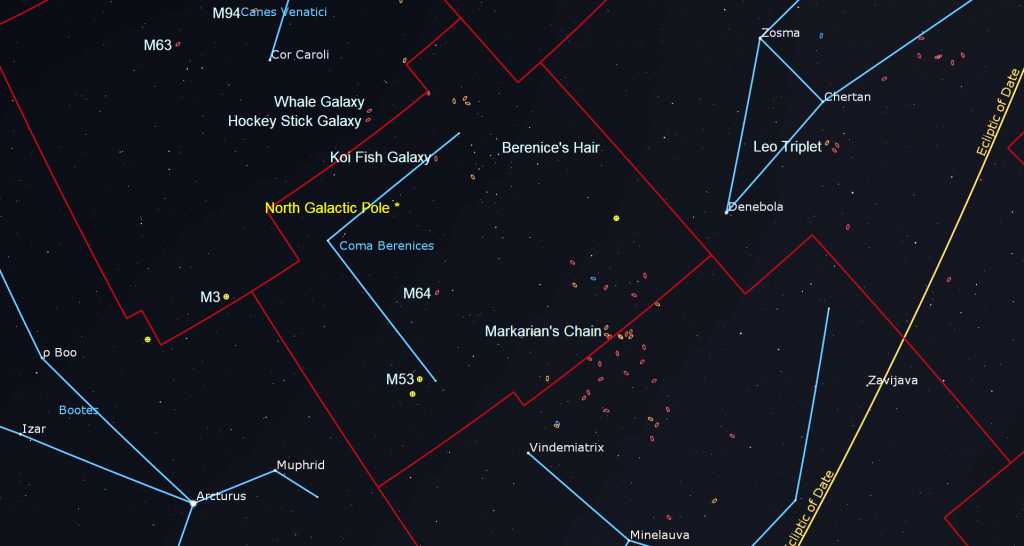

During March, the largest object in the main asteroid belt, named (1) Ceres, will perform a westerly retrograde loop that carries it through the northern edge of the Virgo Cluster of Galaxies. That region of the sky is located about midway between the bright stars Denebola in Leo (the Lion) and Vindemiatrix in Virgo (the Maiden). It contains thousands of galaxies, including quite a few larger ones that are visible in backyard telescopes under a dark sky. Until Friday, 7th magnitude (1) Ceres will be positioned telescope-close to the prominent spiral galaxies named Messier 91 and Messier 88. Don’t forget to hunt around a little for more of the cluster members! They’ll look like oval fuzzy patches.

Ceres will clear the eastern rooftops by about 9 pm local time – but the faint galaxies will be best viewed starting in late evening, when they will be halfway up the southern sky. Telescope-owners can also check out Markarian’s Chain of galaxies, which arcs to the right (or celestial southwest) of both Messier 91 and 88. (I published an article about viewing Markarian’s Chain in the current issue of SkyNews Magazine, which is available now at Canadian news stands.)

Both speedy Mercury and distant Neptune are out of sight worldwide while they pass the sun this week. Over the coming weeks Saturn will gradually return to visibility in the east before sunrise. The waning crescent moon will join it just above the east-southeastern horizon next Sunday morning.

Leo Guides Us to Galaxies

The bright moon’s departure from the evening sky worldwide this week will officially open galaxy-viewing season! That’s a roughly two month window when the Milky Way descends to the horizon, leaving the evening sky overhead free of its obscuring gas and dust, and letting us peer into the deep Universe at the other galaxies there! On the dates when the moon is close to the daytime sun or rises after midnight, we are treated to especially dark skies for hunting these faint, but majestic objects. This year, those blocks of time are now to March 21 and again from to April 11 to 22. Plan your cottage and camping visits with that in mind!

The best places to find galaxies are between the constellations of Leo (the Lion) and Virgo (the Maiden), and the constellations above them, Coma Berenices (Berenice’s Hair), Canes Venatici (the Hunting Dogs), and Ursa Major (the Big Bear). That’s because the spot on the celestial sphere that points directly out of our Milky Way galaxy’s disk, the North Galactic Pole, is located in Coma Berenices. To better acquaint you with the sky, let me introduce you to Leo, the Lion.

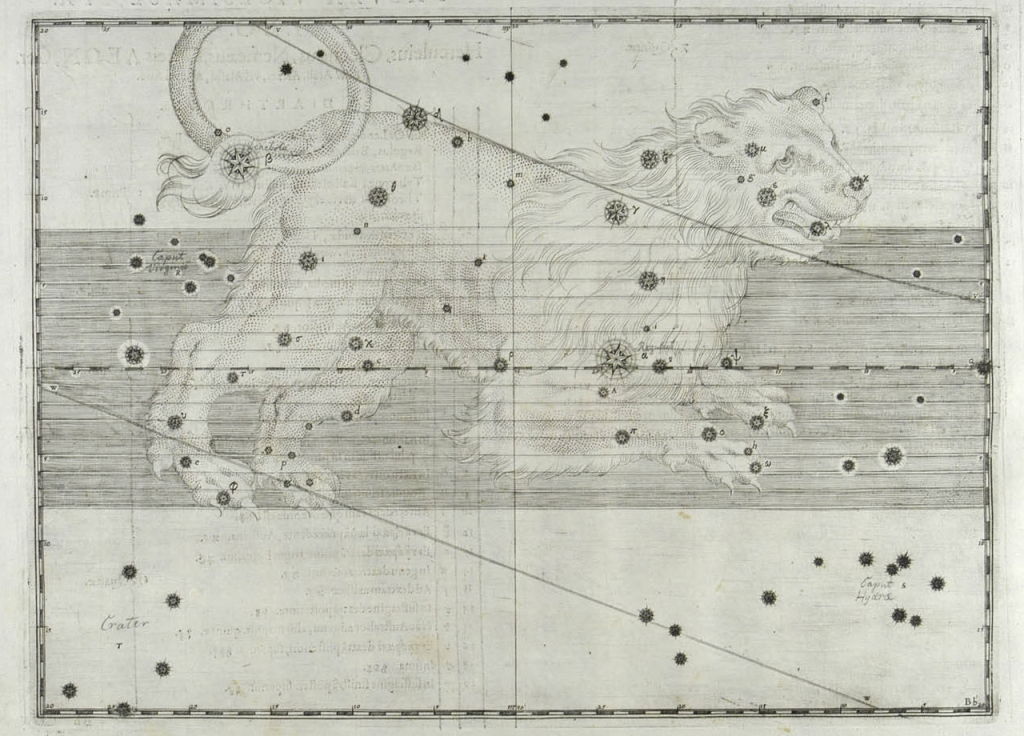

For millennia, sky-watchers have imagined the stars in the night sky linking into patterns – forming humans and animals and inanimate objects. We call these groupings constellations, after the Latin for “stars grouping together”. Each culture has assigned their own spin on the heavens, usually naming the patterns after things in their everyday experience. For example, south sea islanders saw outrigger canoes. The Inuit in the north saw the Big Dipper as the Caribou and Cassiopeia’s “W-shape” as the Blubber Container, with a Lamp Stand shining nearby.

In modern-day astronomy, the entire sky is divided into 88 officially recognized constellations. The manner in which the stars are connected into stick figures is not regulated, but the boundary lines between the constellations are. That way, there are no gaps in the coverage, and every object in the heavens can be placed within one of the 88 regions. By the way, astronomy has a long tradition in China – and they connected smaller groups of stars, yielding several hundred Chinese asterisms or 星官, xīngguān.

A handful of constellations are so obvious that many independent cultures assigned the same meaning to those stars. A perfect example of that is the spring constellation of Leo (the Lion). The lion was identified as early as 1,000 BCE by the Babylonians, and later by the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans. To the Greeks it represented the Nemean Lion slain by Hercules during his labours. Only that beast’s own claws were sharp enough to slice its hide.

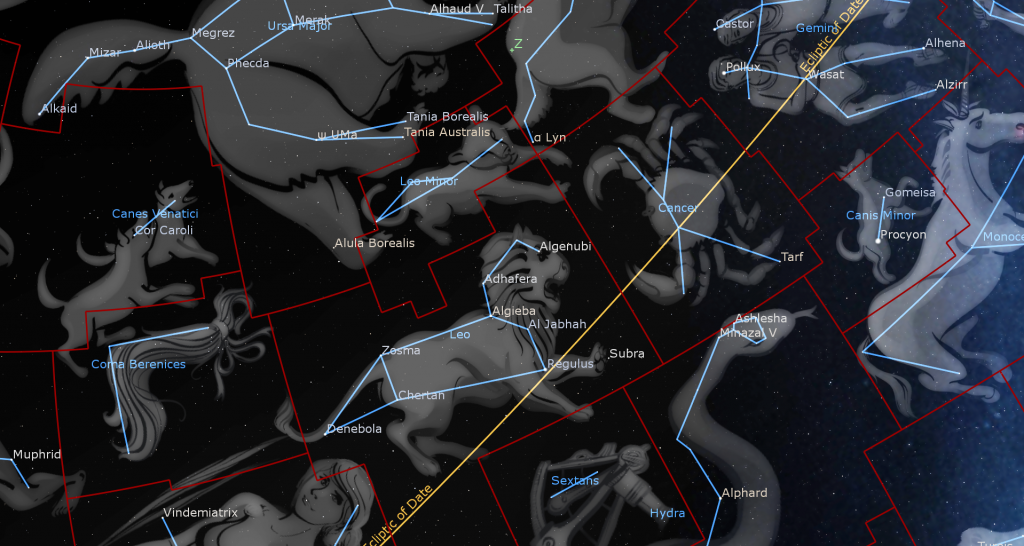

It’s easy to find and recognize Leo, even from suburban skies. Head out on the next clear evening and face east. Leo is a large constellation situated halfway up the evening sky. The imaginary ecliptic line that the Sun, Moon, and planets all travel close to crosses through the lion. For this reason, Leo is one of the twelve zodiac constellations. He is positioned with his head facing upper right (celestial west) and his tail down towards the left (east). In some depictions, he has no legs or feet, as if he’s got them tucked underneath himself! Tilted tail downwards in early evening, the lion will level out in the southern sky around midnight, and then descend headfirst in the west until almost dawn.

The lion’s brightest star is Regulus (or Alpha Leonis). Regulus means “Little King” in Latin and its Arabic name Qalb Al Asad translates to “the heart of the Lion”. Regulus, the 21st brightest star in the heavens, is a blue-white star with a small, nearby companion star that can be seen in binoculars or a backyard telescope. Its position very close to the ecliptic allows it be occulted frequently by the moon and the inner planets.

From Regulus, look upwards and trace out another five modestly bright stars arranged in a backwards question mark about 1.4 fist diameters tall with Regulus serving as the “dot”. Some people see a sickle. The shape represents the lion’s neck, head, and mane. The medium-bright, white star that sits a slim palm’s width above Regulus is Al Jabhah (or Eta Leonis). It emits up to 20,000 times more light than our own sun, but its distance of 1,270 light-years makes it dim enough to shine near the limit of visibility for suburban stargazers.

The second star up from Regulus shines several finger widths to the upper left (or 4° to the celestial northeast) of Al Jabhah. This is a brighter star named Algieba, or “the forehead”. In a backyard telescope, Algieba splits into a very pretty yellow and blue pair of stars, one slightly brighter than the other. A third star shines well-separated from the pair. The medium-bright, yellowish star positioned above Algieba is Adhafera (or Zeta Leonis), which comes from the Arabic aḍ-ḍafīrah “the braid/curl”, possibly a reference to its position in the lion’s mane. The star is flanked by two bright companion stars when viewed in a backyard telescope.

The next star, found with a larger hop toward Adhafera’s upper right, is Rasalas or Ras Elased Australis (or Mu Leonis), an abbreviation of Al Ras al Asad al Shamaliyy, which means “The Lion’s Head toward the South”. Yellow-tinted Rasalas is only about 125 light-years away from us, and is known to be orbited by a giant planet. At the end of the sickle, a bit lower than Rasala, we find medium-bright, yellow star Algenubi (or Epsilon Leonis), which marks the beast’s nose. Both Algenubi and Ras Elased Australis mean “the Southern Star of the Lion’s Head”.

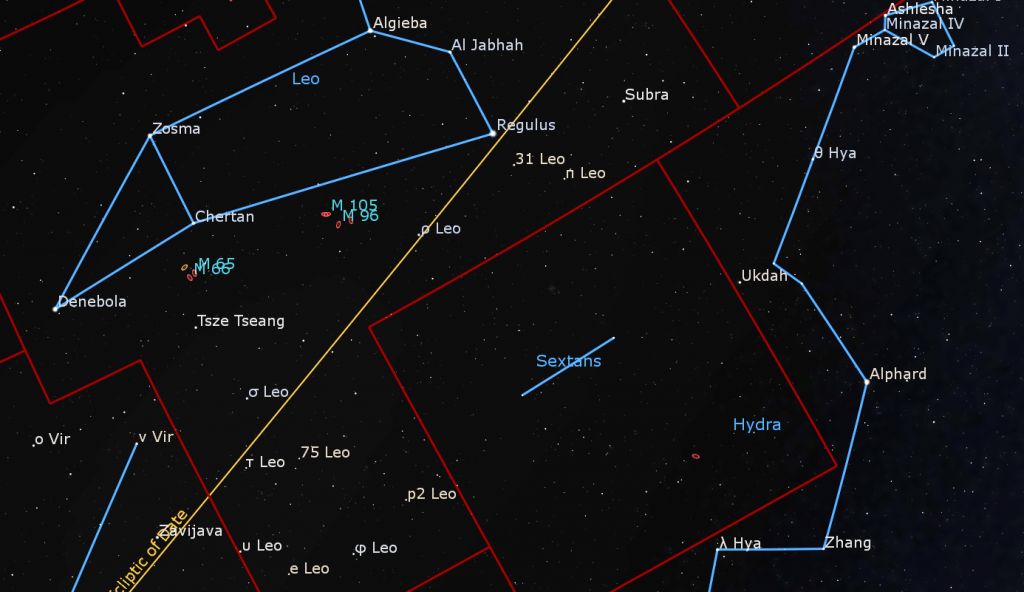

A fainter, reddish star named Alterf (or Lambda Leonis) shines just a few finger widths in front (west) of the lion’s nose. The name arises from the Arabic word Aṭ-ṭarf “the View (of the Lion)”. A very similar red star named 31 Leonis shines a short distance below Regulus. And, and even redder star named Pi Leonis shines to finger widths below and to the right of 31 Leonis. Check them out in binoculars!

Let’s trace out the rest of the lion. Starting from Algieba, cast your gaze a generous fist’s width to the left (or 13° to the celestial east) to find a star of similar brightness named Zosma (or Delta Leonis). It represents the lion’s hip. Zosma is a hot, white star about twice the diameter of our sun – although its rapid spin (100 times faster than our sun’s) has given it an oblate form. We know so much about the star because it only 54 light-years away.

Angling down and to the left of Zosma by another fist’s width, we reach the star marking the lion’s tail, Denebola (or Beta Leonis), the second brightest star in the constellation. Denebola is a young, blue-white star only a few hundred million years old. It emits quite a bit of infrared radiation, suggesting that this young sun may have a planet-forming dust disk around it. It’s a mere 36 light-years away from us!

The last major star of Leo, named Chertan (or Theta Leonis), sits to the lower right of Zosma and Denebola, forming a nice triangle with the other two stars. The name Chertan is derived from the Arabic al-kharātān “Two Small Ribs”, which originally referred to the up-down line formed with Zosma.

Draw an imaginary line from Zosma to Chertan and triple its length. If you aim your binoculars at that seemingly empty patch of sky you’ll discover a rough circlet of medium-bright stars about a fist’s width (or 10 degrees) across named Sigma, Tau, Upsilon, Epsilon, Phi, p, and d Leonis. I like to think of them as outlining the mouth of the lion’s den.

Now that you see the lion – can you see the mouse? It’s easy to imagine the sickle of stars as a mouse’s curly tail, and Denebola and Zosma as the mouse’s nose and eye!

Leo is a favorite of amateur astronomers because it contains a nice selection of relatively nearby and bright galaxies – and Chertan is your guidepost to finding them!

A medium-bright star named Iota Leonis (or Tsze Tseang in some apps) shines to the lower left (or celestial south-southeast) of Chertan. (It’s the same distance from Chertan that Zosma is.) On a moonless night in a location away from city lights, aim your big binoculars or a backyard telescope halfway between Chertan and Iota. There, you should see a clump of three spiral galaxies known as the Leo Triplet. All three galaxies will share the eyepiece in a good telescope at low magnification. Two of the galaxies sit closer together. Those are numbers 65 and 66 on Charles Messier’s famous list of deep sky objects, so astronomers call them M65 and M66. A third, fainter galaxy sits a little bit apart. That’s the Hamburger Galaxy, or NGC 3628, so-named for its distinctive shape.

A second, more widely separated group of galaxies is located midway between Chertan and Regulus, and two finger widths below the line joining those two stars. Named the Leo I Group, it contains M95, M96, and M105 – plus another galaxy not catalogued by Charles Messier named NGC 3384. NGC stands for New General Catalog.

And that’s just the beginning. A very nice and bright spiral galaxy named NGC 2903 sits just a thumbs width below (or 1.4° to the celestial south of) the star Alterf. Let’s call it the Lion’s Tongue Galaxy.

Moreover, the patch of sky located about a fist’s diameter to the rear of Denebola contains dozens of bright galaxies! But that’s a story for another time…

I presented a deep dive into Leo’s best features in April, 2023. The YouTube link to it is here.

Evening Zodiacal Light

If you live in a mid-northern latitude location where the sky is free of light pollution, you might be able to spot the Zodiacal Light, which will appear during the two weeks that precede the new moon on Tuesday, March 21. After the evening twilight has disappeared, you’ll have about half an hour to check the western sky for a broad wedge of faint light extending upwards from the horizon and centered on the ecliptic above the planets Venus and Jupiter. That glow is the zodiacal light – sunlight scattered from countless small dust particles that populate the plane of our solar system. Recent studies point to Mars as a major contributor to the dust! Don’t confuse the zodiacal light with the winter Milky Way, which extends upwards from the northwestern evening horizon at this time of year. I posted a diagram of it here.

The Gems of Gemini

If you missed my tour through Gemini (The Twins) from last week, I posted it here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras (weather permitting), answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. On Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

It’s March Break time in Ontario! The RASC Toronto Centre astronomers will be hosting a variety of in-person activities for families at the David Dunlap Observatory in Richmond Hill. The full list of events and details are available at www.rascto.ca.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcast with RASC National returns on Tuesday, March 14 at 3:30 pm EST. Since it’s March Break, we’ll tour the early spring sky and showcase sights to see with unaided eyes, through binoculars, and in telescopes of any size. Then we’ll wrap up by highlighting the next batch of RASC’s Finest NGC objects. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!