The Mid-summer Waning Morning Moon Promotes Perusing of Perseids and Looking at Lyra!

Bill Longo of Toronto captured this amazing sequence of images on August 15, 2014. The International Space Station climbs the sky through the Big Dipper at left, while a Perseids meteor briefly streaks across the sky at right.

Hello, Meteor Lovers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of August 6th, 2023 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

If you’d like me to bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or deliver a session online, contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together! My terrific book with John A. Read entitled 110 Things to See With a Telescope is a guide to viewing the deep sky objects in the Messier List – for both beginners and seasoned astronomers. DM me to order a signed copy!

The northern cross-quarter day marks mid-summer this week. The moon will wane in phase and rise later and later each night this week, setting the stage for dark skies arriving in time for the annual Perseids meteor shower next weekend, and allowing stargazers to explore the sights in Lyra and the other summer constellations near the Milky Way. I break down the meteor shower and share a tour of Lyra. Meanwhile, Mercury and Mars will shine faintly near one another above the western horizon after sunset, and Jupiter and Uranus will join Saturn and Neptune in the midnight sky. Read on for your Skylights!

Mid-Summer

The daylight hours are shortening at a faster rate now for mid-northern stargazers. Over the course of this week, we’ll swap almost 18 minutes of daylight for night. That pace will increase until the first day of autumn.

Monday, August 7 at 2:21 pm EDT (or 18:21 Greenwich Mean Time) will mark the mid-point of summer in 2023 – falling halfway between the June Solstice and the September Equinox. It is one of the four so-called cross-quarter days, which are the season midpoints following each solstice and equinox. Many pagan groups schedule Lammas or Lughasadh festivals around this time – to celebrate the early harvest. The term “lammas” refers to grain or bread. (Tolkien readers will notice that it resembles the word “lembas”, the Elven Waybread, from the same root.) The next cross-quarter day will occur in three months, during the first week of November. That’s Samhain. But we celebrate it on October 31 – as Halloween!

The Earth reaches it farthest distance from the sun, or aphelion, in early July each year. Since Kepler’s Laws of Planetary Motion dictate that a planet moves slowest while at aphelion, summer in the Northern Hemisphere is several days longer than winter! Enjoy!

Perseids Meteor Shower

The annual Perseids Meteor Shower is the one I look forward to the most. While December’s Geminids and January’s Quadrantids deliver more meteors per hour at their peaks (150 and 120, respectively), cloudy winter skies and bitter cold aren’t conducive to enjoying their displays. The Perseids shower, on the other hand, delivers 60 to 100 meteors per hour at its mid-August peak, which always arrives during the hot, dry part of summer at mid-northern latitudes. Perseids are famous for appearing as bright, sputtering fireballs! Some leave “smoke trails” that dissipate in a few minutes.

Meteor showers re-occur on the same dates every year when Earth’s orbital motion around the sun carries us through zones of small particles left behind by multiple passes of periodic comets. When those comets sweep through the inner solar system, the warmth of the sun causes them to outgas and eject dust-sized and sand-sized (and sometimes larger) cometary particles along their orbit. Over many orbits (i.e., many years), the material accumulates within an elongated, tube-shaped cloud in interplanetary space. An analogy is the material that falls out of a dump truck as it rattles along. The roadway eventually gets pretty dirty after the truck drives the same route a number of times – and there’s no wind or rain in space to wash it clean.

For 2023, the Perseids shower will peak on a nearly moonless night! My friend Blake Nancarrow has prepared a very informative chart here that shows how the number of meteors varies throughout a given year. Unfortunately, moonlight obscures meteors by brightening the sky, and Blake’s graph would have to be remade each year to take that into account. Earth’s orbit intersects or passes close to the orbits of quite a few comets. Blake’s graph shows about 20 significant meteor showers – but some of them are produced by the same comet’s orbit intersected twice. He has omitted other, very minor showers.

When the Earth plows through the debris cloud, some of its particles are caught by our gravity and burn up as they fall through our atmosphere at speeds on the order of 200,000 km/hr. The friction caused by grains moving that quickly through the air generates intense heat that ionizes the air along its path – producing the long glowing trails we see.

The duration of a meteor shower depends on the width of the particle cloud in space and the angle at which we intersect it, i.e., how long Earth takes to pass through it. The number of meteors will increase nightly as Earth ventures more deeply into the debris field, peak when the particles are most plentiful, and then taper off on the following nights. If the moon is going to be shining in the sky on peak night, you can often arrange to do your meteor-watching a night or two ahead or after the peak, when the moon won’t as bad. I usually work that out for you.

The shower’s intensity depends on the type of particles in it, and on whether we pass through the densest portion of the debris field, or merely skirt the edges. Due to small variations in orbits any shower’s performance can vary from year to year, independent of the moon. The source of the Perseids material is thought to be a large, 133-year-period comet named 109P/Swift-Tuttle, which was discovered by Lewis Swift and Horace Tuttle in 1862. When it last passed Earth in 1992, it wasn’t visible – but astronomers predict that its 2126 pass could be spectacular! Here’s a link to a 3D model of the comet’s path through the solar system and the Perseids shower. Drag your mouse around to view the geometry.

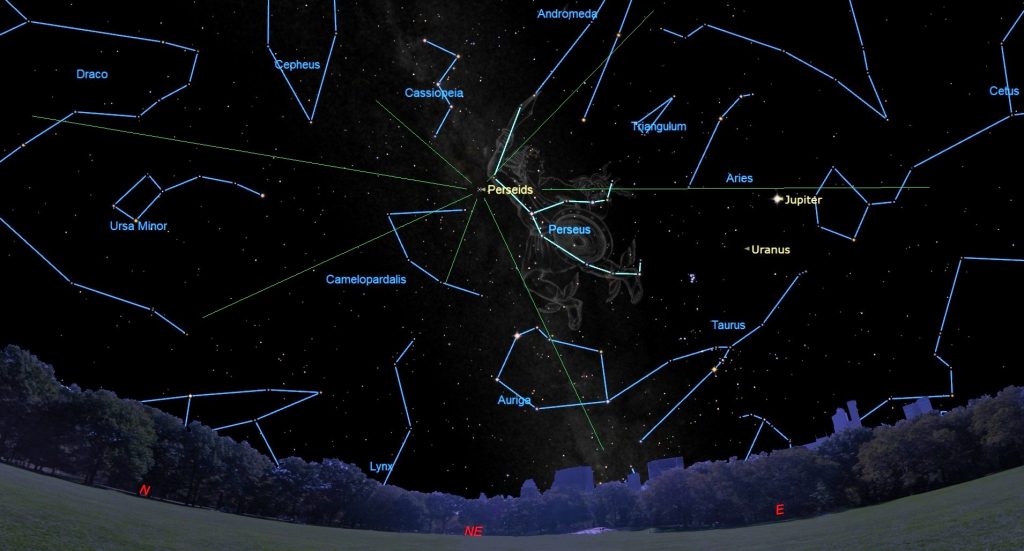

While visible anywhere in the night sky, meteors will appear to be travelling away from a location in the sky called the radiant. The radiant for the Perseids sits in northern Perseus (the Hero) – near its brightest star Mirfak and Perseus’ border with Camelopardalis (the Giraffe). Meteor showers are strongest before dawn because that’s the time when the sky over your head is plowing directly into the oncoming debris field, like bugs splattering on a moving car’s windshield. When the radiant is overhead, the entire sky down to the horizon is available for meteors. When the radiant is low, many of the meteors are hidden below the horizon. The Perseids’ radiant is low in the northeastern sky during mid-August evenings – and nearly overhead by dawn. You don’t need to know where the radiant is – only when it’s higher.

The active period for the Perseids shower will be about July 14 through September 1, ramping up towards the peak night and then tapering off. It will peak after midnight in the Americas on Saturday night, August 12. That means that the best time for seeing Perseids meteors in North America will be the hours before dawn on Sunday morning, when the shower’s radiant in Perseus will be high in the northeastern sky. That morning, the 8%-illuminated waning crescent moon will rise at around 3 am local time. The moon will be brighter and in the sky for more of the night on dates before Saturday-Sunday and almost a complete non-issue afterwards. So, is the sky is cloudy on Saturday-Sunday, check on Sunday-Monday.

The nickname for meteors is “shooting stars” or “falling stars”, but they bear no physical connection to the distant stars. The action is taking place about 100 km over your head within Earth’s blanket of atmosphere. All of our favourite constellations look the same as ever at the end of a shower! That said, though, each shower’s name comes from the location of its radiant – the stars that Earth is traveling towards on the peak night. (That spot on the celestial sphere shifts each night because we are travelling in an ellipse around the sun.) Some showers are named for defunct constellation (Quadrantids), others use a particular star within a constellation (Delta Aquariids), or a region of a constellation (Southern Taurids).

To see the most meteors, try to find a safe, ideally rural, viewing location with as much open sky as possible. If you can hide bright lights behind a building or tree, that will help. You can start watching as soon as the sky becomes dark. That’s a good time to catch the rarer, very long meteors produced by particles skipping across the Earth’s upper atmosphere. Don’t worry about watching the radiant. Meteors near it will be heading directly towards you and will have very short trails. When you see a meteor, try to trace its path backwards to see if it points to Perseus. Sporadic meteors won’t!

Bring a blanket for warmth and a chaise to avoid neck strain, plus snacks and drinks. Try to keep watching the sky even while chatting with friends or family – they’ll understand. Call out when you see one; a bit of friendly competition is fun!

Don’t look at your phone or tablet – its bright screen will spoil your dark adaptation. If you must use a screen, turn the brightness down, or cover it with red film. Disabling app notifications will reduce the chances of unexpected bright light, too. And remember that the narrow fields of view that binoculars and telescopes will not help you see meteors.

The Southern Delta Aquariids meteor shower, caused by the Earth passing through a cloud of tiny particles dropped by a periodic Comet 96P/Machholtz, will be tapering off until August 23. Those meteors will appear to travel away from that shower’s radiant, in Aquarius (the Water-Bearer), which sits in low in the southeastern sky during evening. Good luck!

A Look at Lyra

This week’s moonless evenings will be useful for more than meteors! Once the sky becomes fully dark after 10:30 pm local time, tilt your head back and look waaay up – or use that Perseids blanket, gravity chair, or chaise. Point your finger directly overhead. That’s the zenith – the point of the sky directly above you. During the night, various stars and constellations will pass through that patch of sky as the Earth’s rotation carries them from east to west. While stars and other objects occupy that position, they will always appear at their best. That’s because you are looking through the thinnest blanket of intervening air. (Light from objects near the horizon has to pass through as much as ten times more air to reach your eyes – making the objects a blurry mess due to increased atmospheric turbulence!)

In early evening during mid-August every year, the constellations of Lyra (the Harp), Cygnus (the Swan), Hercules, and Draco (the Dragon) occupy the zenith. A while back I wrote a detailed tour of Lyra’s stars, pointing out some objects you can look at with binoculars and small telescopes. In Greek mythology, Lyra was the musical instrument created from a turtle shell by Hermes and later used by Orpheus in his ill-fated attempt to rescue his lost love Eurydice from the underworld. We Canadian astronomers call Lyra the “Tim Hortons Constellation” because it contains both a doughnut and a double-double coffee!

Facing southeast and looking just below the zenith, you’ll easily spot the very bright star Vega, also known as Alpha Lyrae – the brightest star in the constellation. Vega is the fifth brightest star in the entire night sky – partly because it is only about 25 light years away from us, and partly because it is a very hot, luminous star. The name Vega arises from the Arabic “Al Nasr al Waqi”, or the “swooping eagle”. (Pronounce the “W” with a “V” sound.) In traditional star maps, the Lyre was grasped in the talons of a flying eagle.

Vega is moving towards our sun and will continually brighten over time, becoming the brightest star in the night sky a few hundred thousand years from now. Meanwhile, the wobble of the Earth’s axis will also cause Vega to displace Polaris as the northern Pole Star around 14,500 AD. It was previously the pole star around 12,000 BC. This star is a star!

Vega is also the brightest, highest, and most westerly of the three beautiful, blue-white stars of the Summer Triangle asterism. Moving clockwise, Altair is about three fist widths below (or 34° to the celestial south) of Vega. The star Deneb, slightly dimmer than the other two, completes the large triangle at the upper left. The separation between Deneb and Vega is shorter, only 24°, or 2.5 fist widths.

Chinese culture celebrates a love story in which a Cowherd named Niú Láng (牛郎) is the star Altair. Long ago, the Cowherd and his two children, (β and γ Aquilae, the stars that flank Altair) were separated from their mother Zhī Nǚ (織女) the “Weaving Girl” (Vega) – banishing her to the far side of the river, which is represented by the Milky Way. As the story goes, each year, on the seventh day of the seventh month of the Chinese lunisolar calendar, magpies make a bridge across the Milky Way – so that the family can be together again for a single night. Some astronomers believe that the magpies are actually Perseids meteors, which travel parallel to the Milky Way every August.

To continue your exploration of Lyra, head over to the original post that includes labelled star charts of Lyra and a close-up picture of the Ring Nebula here.

The Moon

Lucky for meteor-lovers, this is the week of the lunar month when the moon will transition to the pre-dawn sky. Tonight (Sunday), our natural night-light will rise among the stars of western Aries (the Ram) a short time after 11 pm local time. After crossing the night sky, its pale, waning gibbous orb will linger into morning daytime as an echo of the night.

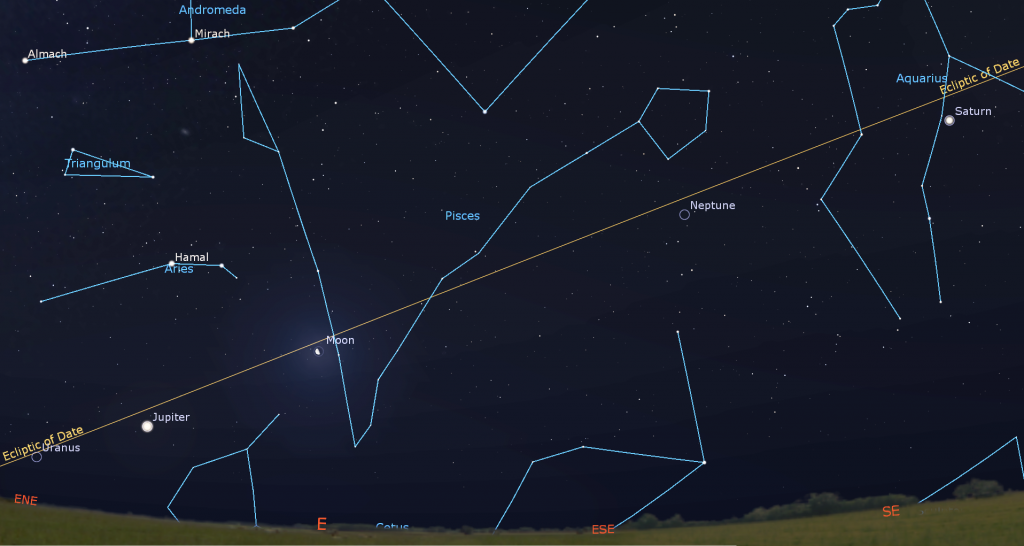

When the half-illuminated moon rises over the eastern horizon just before midnight on Monday, night, it will be accompanied by the brilliant planet Jupiter. The duo will easily share the view in binoculars. By dawn on Tuesday, the moon and Jupiter will be shining in the brightening southeastern sky, making a nice photo opportunity. For a challenge, seek out the pale moon in the daytime sky on Tuesday morning and then use binoculars to look for Jupiter’s small, pale disk shining a few finger widths below it. Always be careful not to aim binoculars anywhere near the sun. In the Eastern Time zone Jupiter will be positioned two to three finger widths below the moon. Sharp eyes might glimpse Jupiter unaided.

Still in Aries, the moon will complete three quarters of its orbit around Earth, measured from the previous new moon, on Tuesday, August 8 at 6:28 am EDT, 3:28 am PDT, or 10:28 GMT. At its third (or last) quarter phase, the moon always appears half-illuminated, on its western, sunward side.

The moon will wane in phase and rise about 40 minutes later each night. When its crescent clears the treetops in the eastern sky on Wednesday morning it will be shining between the bright little Pleiades Star Cluster in Taurus (the Bull) and the ice giant planet Uranus. For observers in the Eastern Time zone, the moon will appear several finger widths to the right (or celestial southwest) of the Pleiades. Uranus, which is visible in binoculars and backyard telescopes, will be shining about the same distance to the moon’s right. Skywatchers viewing the scene later, or in more westerly time zones, will see the moon closer to the Pleiades and farther from Uranus. Very bright Jupiter will shine off to the upper right of the grouping.

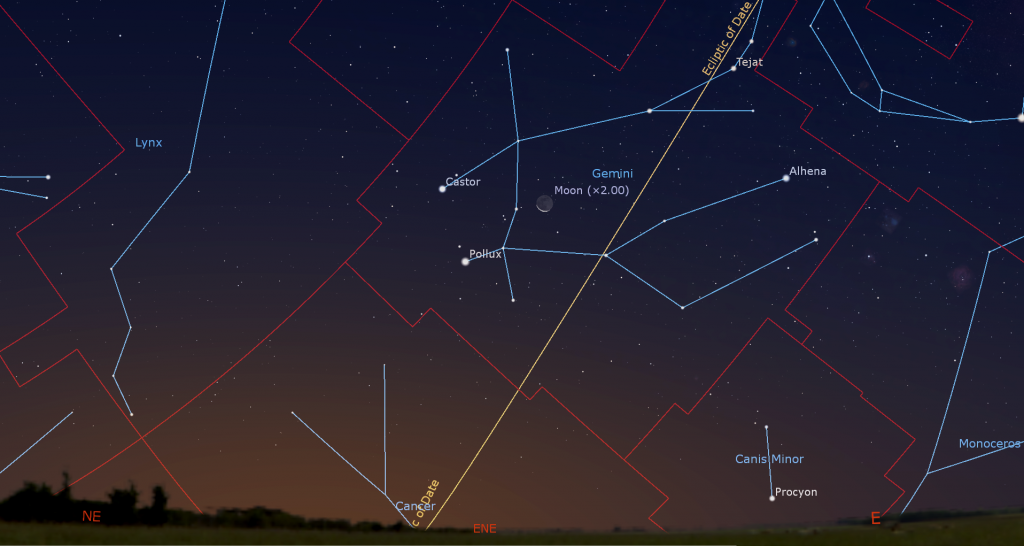

The crescent moon will spend Thursday and Friday in Taurus – creeping past the bull’s angry eye, which is marked by the bright star Aldebaran, on Thursday, and then shining just to the lower right of the northern horntip star Elnath on Friday morning. The moon’s slim crescent will shine among the stars of Gemini (the Twins) on the coming weekend. Early risers next Sunday morning can cap off their Perseids-watching night with the pretty sight of the crescent moon shining in the lower part of the east-northeastern sky and a palm’s width to the right (or celestial southwest) of Gemini’s brightest stars Pollux and Castor. Skywatchers in more westerly time zones will see the moon a little closer to Pollux, the lower, brighter, and more golden of the two stars.

The Planets

Once the sun has completely sunk out of sight this week, use binoculars to scan less than a palm’s width above the western horizon for Mercury’s magnitude 0.18 speck. In a telescope, the planet will show a waning, half-illuminated phase that swims and dances in the turbulent air. At sunset on Wednesday, Mercury will be hours away from its widest separation of 27 degrees east of the Sun, and its maximum visibility for the current apparition. With Mercury positioned in the western sky below the severely tilted evening ecliptic, this appearance of the planet will be a very poor one for Northern Hemisphere observers, but it will offer good views for observers located near the equator and farther south, where the surrounding stars of Leo (the Lion) may appear. The optimal viewing times at mid-northern latitudes will be around 8:45 pm local time.

Much fainter, magnitude 1.77 Mars is moving eastward through Leo in the western sky, too – delaying its conjunction with the sun for weeks to come. Mars will begin this week positioned a palm’s width to Mercury’s upper left. Next weekend, Mercury will approach to within 4.7° of Mars, or about the width of your flat fingers.

Just as Mercury and Mars are setting at about 9:30 pm local time, the bright, yellowish dot of Saturn will be rising over the east-southeastern horizon. It’ll climb high enough to clear the rooftops about an hour later – but the clearest views of Saturn in a telescope will fall between midnight and dawn. If you head outside by about 5 am, you’ll still be able to see the stars of Aquarius (the Water-Bearer) shining around Saturn, and the bright trio of the Summer Triangle asterism stars shining well off to its upper right. The very bright star Fomalhaut (or Alpha Piscis Austrini, the Southern Fish) will shine two fist diameters below Saturn during this year.

Saturn and its beautiful rings are visible in any size of telescope. If your optics are of good quality and the air is steady, try to see the Cassini Division, a narrow gap curving between the outer and inner rings, and a faint belt of dark clouds that encircle the planet’s globe. Remember to take long, lingering looks through the eyepiece – so that you can catch moments of perfect atmospheric clarity. Good binoculars can hint at Saturn’s rings, too.

From here on Earth, Saturn’s axial tilt of 26.7° lets us see the top of its ring plane, and allows its brighter moons to array themselves above, below, and alongside the planet. Saturn’s largest and brightest moon Titan never wanders more than five times the width of Saturn’s rings from the planet. The much fainter moon named Iapetus can stray up to twelve times the ring width during its 80-day orbit of Saturn. The next brightest moons Rhea, Dione, Tethys, Enceladus, and Mimas all stay within one ring-width of Saturn.

During this week, Titan will migrate counter-clockwise around Saturn, moving from just to the planet’s upper right (celestial west-northwest) on Sunday night to Saturn’s lower left (celestial east) next Sunday night. (Remember that your telescope will probably flip the view around.) How many of the moons can you see in your telescope? You may be surprised at how many you can see if you look closely. Saturn will be available for our evening viewing pleasure through its opposition in late August and then on until mid-winter! This summer the blue ice giant planet Neptune, currently 840 times fainter than Saturn, will be lurking two fist diameters to Saturn’s left, or 22° to its celestial northeast.

Brilliant, white Jupiter, which currently shines about 15 times brighter than Saturn, will start to rise just before midnight local time this week, officially making it a summer stargazing planet! Jupiter will appear about half an hour earlier with each passing week, and will become better and better positioned for after dinner stargazing as we progress through autumn and winter. This year Hamal and Sheratan, the brightest stars of Aries (the Ram), will shine a generous fist’s diameter above the giant planet. Jupiter will probably catch your eye while it gleams high in the southern sky before sunrise.

Binoculars will show you Jupiter’s four Galilean moons in a line beside the planet. Named Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto in order of their orbital distance from Jupiter, those moons complete orbits of the planet every 1.7, 3.6, 7.2, and 16.7 days, respectively. If you see fewer than four moons, then one or more of them is crossing in front of or behind Jupiter, or hiding in Jupiter’s dark shadow – or two of the moons are very close together or occulting one another. All four of them will huddle to the west of Jupiter on Saturday morning.

Jupiter will climb high enough for good telescope views after about 1:30 am local time, and improving thereafter. Even a small, but decent quality telescope can show you Jupiter’s dark belts and light zones, which are aligned parallel to its equator. With a better grade of optics, Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a cyclonic storm that has raged for hundreds of years, becomes visible for several hours when it crosses the planet every 2nd or 3rd night. For observers in the Americas, that GRS will cross Jupiter’s disk on early on Friday and Sunday morning, and before dawn on Tuesday, Thursday and next Sunday morning. If you have any coloured filters or nebula filters for your telescope, try enhancing the spot with them.

From time to time, the small, round, black shadows cast by Jupiter’s Galilean moons become visible in amateur telescopes when they cross (or transit) the planet’s disk. On Monday morning, August 7, Europa’s small shadow will cross Jupiter’s southern hemisphere from 12:50 to 3:05 am EDT (or 04:50 to 07:05 GMT). On Saturday morning, August 12, Io’s small shadow will cross Jupiter’s equatorial region from 1:10 to 3:15 am EDT (or 05:10 to 07:15 GMT).

The blue-green ice giant planet Uranus will be following Jupiter across the sky this year. This week it will be located less than a fist’s diameter to the bright planet’s lower left (or 8.5° to the celestial east). The bright little Pleiades Star Cluster will be located the same distance to Uranus’ left. Magnitude 5.8 Uranus is visible in binoculars and small telescopes if you know where to look. I’ll share details in the coming weeks when it will climb higher.

Public Astronomy-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. They host in-person viewing on the first clear Wednesday night each month. Other Wednesdays they stream views online via the observatory YouTube channel. Details are here.

On Saturday, August 12 from 8 to 11:30 pm EDT, astronomers from the RASC Toronto Centre will host a Perseids Meteor Shower Watch Party at the Rouge Valley Conservation Centre (RVCC), located at 1749 Meadowvale Rd, Scarborough, ON M1B 5W8. They also plan to observe some deep space targets and beautiful Saturn through telescopes! There will be a 20 – 30 minute talk before dark about the meteors and sky that night, and hot chocolate for those who bring their own mugs. As this is weather-dependent, please check the https://rascto.ca/website for a Go/No-Go decision before heading to the RVCC. Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcast with RASC National returns on Tuesday, August 29 at 3:30 pm EST. The Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy team will head to York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory for a live tour and chat about York U’s astronomy program and outreach activities. We’ll end the show by highlighting our final batch of RASC Finest NGC objects. You can find more details and the schedule of future sessions here.

Space Station Flyovers

The ISS (or International Space Station) will not be visible over the Greater Toronto Area this week.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!