The Pretty Crescent Moon Meets Morning Planets and Moves Over Mars, Inner Planets at Sunset, and we Tour the Winter Milky Way!

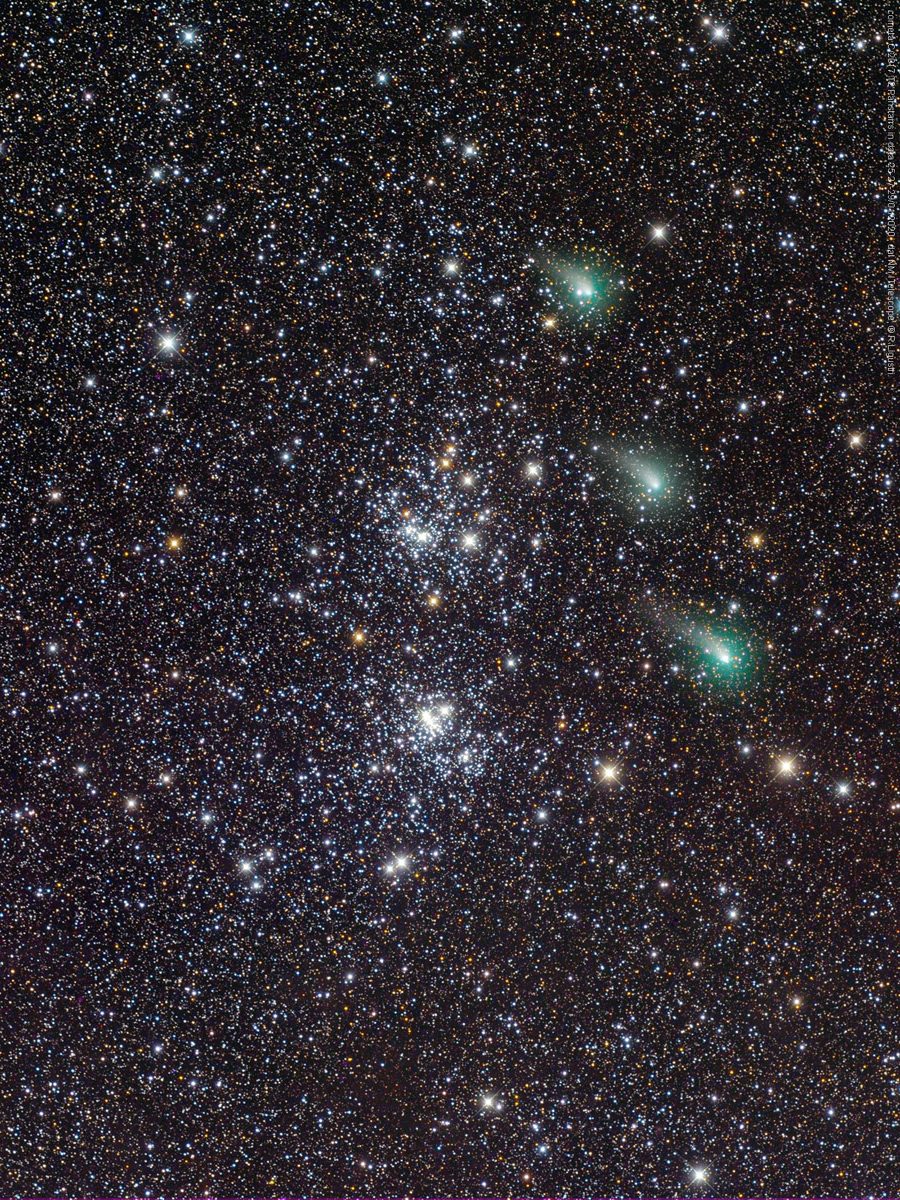

This image shows Comet C/2017 T2 (Panstarrs) passing the Double Cluster in Cassiopeia on January 24, 26, and 28, 2020. It was taken by Rolando Ligustri and appeared as the NASA APOD for January 30, 2020. Comets will exhibit the greenish glow shown here when viewed through a good-quality backyard telescope.

Hello, February Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of February 16th, 2020 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To receive Skylights by email, please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe together!

The moon will be largely absent from night-time skies this week as it slides towards Sunday’s new moon phase. That will provide darker skies around the world – perfect for exploring the treats in the winter Milky Way. Venus, the Goddess of Love, will continue to blaze in the western sky after sunset with Mercury below her. Meanwhile, early risers can enjoy the planetary parade of Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn in the pre-dawn east, and the waning crescent moon touring through them. Here are your Skylights!

Evening Zodiacal light

For about half an hour after dusk this week, observers in the Northern Hemisphere can look west-southwest for a broad wedge of faint light rising from the horizon and centered on the ecliptic. That’s the zodiacal light – sunlight scattered from interplanetary particles of material that are sprinkled throughout the plane of the solar system. Try to observe the zodiacal light from a location without light pollution, and don’t confuse it with the brighter Milky Way, which extends upwards from the northwestern evening horizon at this time of year. Observers in the Southern Hemisphere can see the zodiacal light in the eastern pre-dawn sky starting around February 23.

The Moon and Planets

This is the favorite week of the month for serious astronomers! The evenings between now (Sunday) and next weekend will be the darkest all around the world because the moon will be completing the final week of its monthly trip around Earth. This is the period when the waning moon moves closer to the pre-dawn sun – so the moon rises between midnight and dawn, and then remains visible during morning daylight hours.

On Monday, the waning crescent moon will become visible in the southeastern sky after it rises at about 3 am in your local time zone – making a pretty sight as you head outside to walk the dog, or head to work or school.

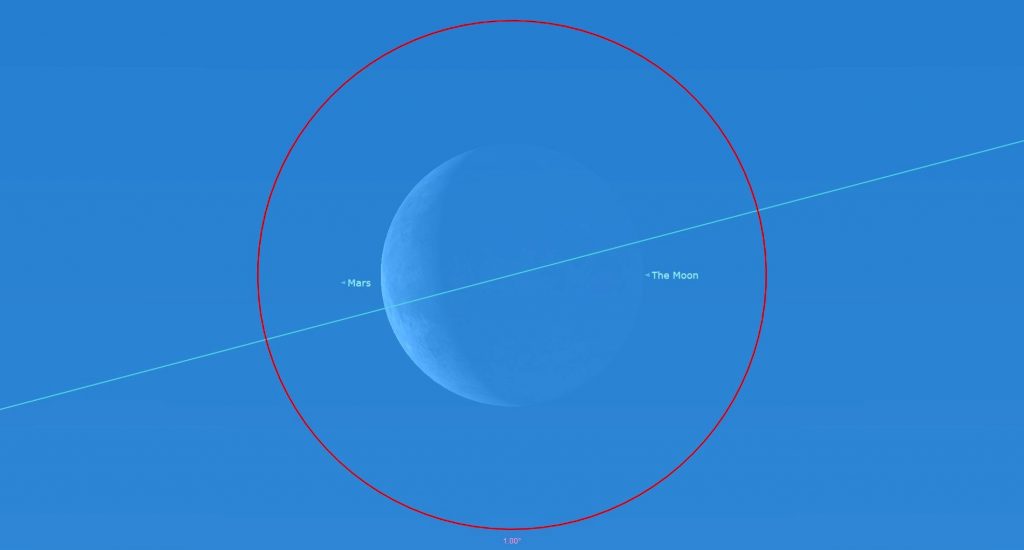

The real treat occurs the next morning. In the southeastern morning sky on Tuesday, February 18, the waning crescent moon will cross in front of (or occult) the planet Mars for observers in North America (except western Canada & Alaska), most of Central America, the Caribbean, northern South America, the southern tip of Greenland, and the Azores. In the Eastern Time zone, the event will begin in daylight at 7:25 am EST when the bright, leading limb of the moon will first cover Mars. The planet will re-appear from behind the moon’s opposite, dark limb at 8:50 am. (The exact ingress and egress times vary depending on your location.) Use good binoculars or a backyard telescope to see the event – although your telescope will flip and/or invert the arrangement I described above. Observers located in the Central, Mountain, and Pacific time zones will get to see the encounter in a darker sky. Let me know if you see it!

On Wednesday morning, the pretty, crescent moon will hop east to sit a few finger widths to the right (or 4° to the celestial west) of the bright planet Jupiter. The pair will be visible quite low in the southeastern sky after they rise at about 5 am local time – until almost sunrise.

The fun continues on Thursday morning, when the moon will hop east again and land a few degrees to the lower right (or 2.5° to the celestial southwest) of dimmer Saturn. This meet-up will be harder to see because the pair will be even lower in the sky, and the sun will be preparing to rise after soon them. But have a go!

Because of how nearly-horizontal the morning ecliptic is at this time of year, Friday morning will offer a final opportunity to see the very slim crescent moon – two days before its new phase. That’s because, even though the moon will be positioned a generous 20 degrees away from the sun on Friday, it will be positioned to the right of the rising sun, rather than above it.

The moon will reach its new moon phase at 10:32 am EST (or 15:32 GMT for the rest of the world) on Sunday. At its new phase, the moon is travelling between the Earth and the sun. Since sunlight is only reaching the side of the moon aimed away from us, and the moon is in the same region of the sky as the sun, the moon is hidden from view for about a day.

As I described above, three bright planets are lined up in the eastern pre-day sky now – Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Over the next several weeks, they’ll put on a show as faster Mars slides close to and between the two gas giants. Stay tuned for updates on those spectacular meetings. For the moment, the three planets are well spaced apart – illustrating how the plane of our solar system spans the sky.

Mars will rise first; at about 4 am local time. The reddish planet is starting to increase in brightness because Earth is moving slowly towards it. Closest approach will occur in October – by which time Mars will be rising at sunset. The relative positions and combined orbital motions of Earth and Mars are causing Mars to appear in roughly the same place in the sky at the same time every morning. However, the planet is actually moving rapidly eastward in front of the distant background stars because they rise four minutes earlier every morning – while Mars does not. Mars will spend the next six weeks crossing the stars of Sagittarius (the Archer).

Sagittarius straddles the Milky Way. During mornings this week, the orbital motion of Mars will carry it close to several bright deep sky objects. On Monday, look for the Trifid Nebula (Messier 20) and the open star cluster Messier 21 sitting less than a finger’s width to the upper left (or 0.5° to the celestial north) of Mars. The Lagoon Nebula (Messier 8) will be positioned one finger’s width below Mars, making those objects easy to find in binoculars and backyard telescopes. Mars will also be sitting less than a palm’s width below a very bright clump of stars known as Messier 24, also known as the Sagittarius Star Cloud. There are lots and lots of star clusters and nebulas in the area!

Next in the morning planet parade is very bright Jupiter, which will be sitting 1.7 fist diameters to the lower left (or celestial east) of Mars. If your southeastern horizon is low and free of obstacles, try and spot Jupiter after it rises around 5 am local time.

Last in line, yellow-tinted Saturn will be situated quite low in the eastern pre-dawn sky – about a fist’s diameter to Jupiter’s lower left. This week the Ringed Planet will rise just before 6 am local time. Good news – every week from here on out, the two gas giants will rise earlier – placing them higher in the sky for your viewing pleasure! By summer, all three planets will be visible for your summer evening stargazing.

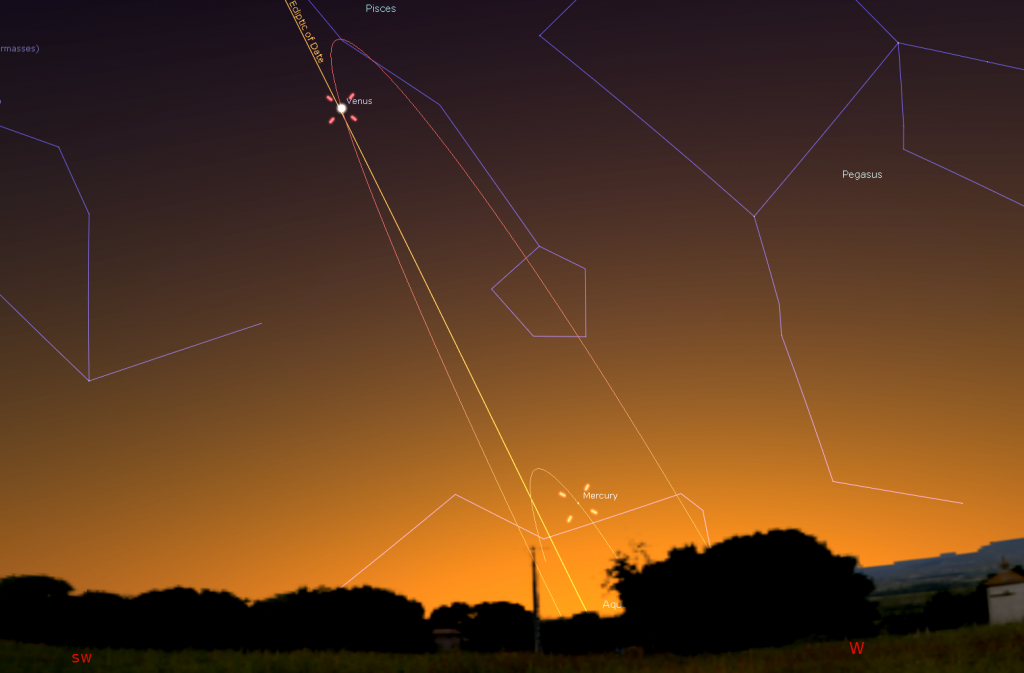

The two innermost planets are visible in the western evening sky. Mercury is completing its best evening appearance during 2020 for equatorial and Northern Hemisphere observers around the world – so we’ll only have this week to catch it. Tonight (Sunday) after sunset, Mercury will set at about 7:10 pm local time – making it relatively easy to pick out the speedy planet sitting a generous palm’s width above the west-southwestern horizon after sunset. The optimal viewing time for Mercury will fall between 6:15 pm and 6:30 pm in your local time zone. Mercury can be easily seen with unaided eyes in a cloud-free sky. If you use binoculars to hunt for Mercury, make sure that the sun has already completely sunk out of sight first.

That incredibly bright “star” that you’ve been seeing in the southwestern sky every evening recently is Venus, the Goddess of Love, or the “Evening Star”. She’ll gleam in the western evening sky until spring. This week, Venus will set in the west after 9:30 pm local time. If you want to see Venus’ less-than-fully-illuminated disk in your telescope, try to view it as soon as you can find it, while Venus is higher in the sky. That way you’ll be viewing the planet through less of Earth’s distorting atmosphere.

The only other observable evening planet is Uranus. The blue-green planet can be seen for a few hours after dusk (it sets at about 11:15 pm local time). Uranus is located a generous palm’s width above (or 7° to the celestial east of) the modest stars that form the V-shaped constellation of Pisces (the Fishes). To be more accurate, Uranus is actually located within the boundary of Aries (the Ram) – to the lower left (or to the celestial south of) that constellation’s two brightest stars, Sheratan (the lower, more westerly star) and Hamal (the higher, more easterly star). The planet is also a fist’s diameter to the right of the ring of stars that form the head of Cetus (the Sea-Monster).

Shining at magnitude 5.8, Uranus is bright enough to see under dark sky conditions with unaided eyes and with binoculars – or through small telescopes under less-dark conditions. To help you find it, I posted a recent, detailed star chart here. If you view Uranus right after the sky darkens at about 7 pm, it will be higher – and you’ll be looking through the least amount of Earth’s disturbing atmosphere.

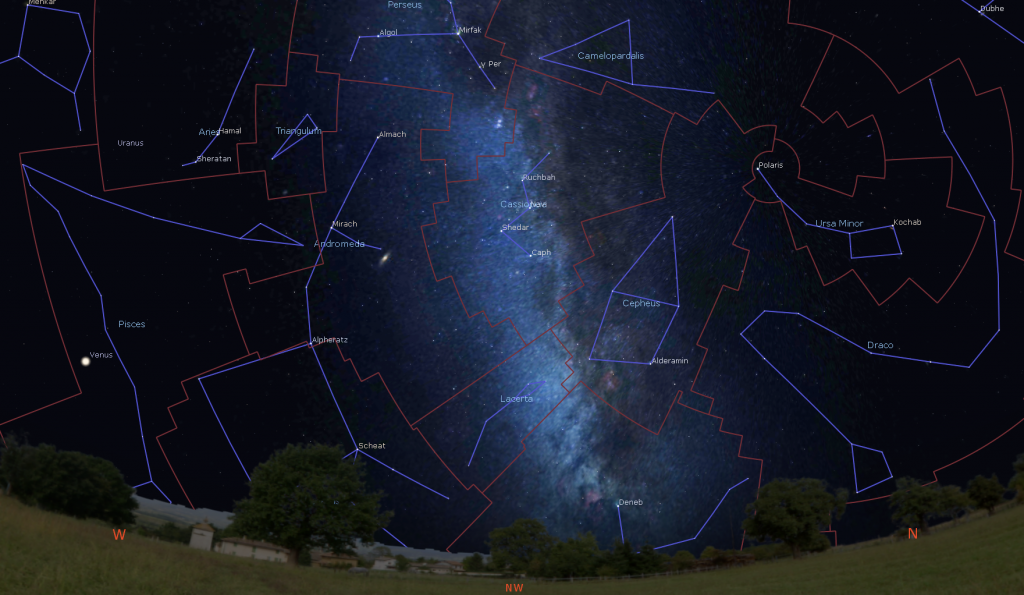

Follow the Winter Milky Way

Our solar system sits inside the vast flattened disk of our galaxy, about one-third of the way towards the outer edge. So the faint band of the Milky Way, composed of countless stars in our galactic disk, can be traced in a huge circle around the sky. The core of the galaxy, and therefore most of the stars, is visible on summer nights. But the outer rim sits in the opposite direction – gracing our winter evening skies. Except for a period in late spring when the Milky Way aligns with the horizon, there’s always a part of it visible in the night sky.

On a clear night, especially this week, when the moon leaves the night sky dark, head outside to an open area away from city lights and look for the outer reaches of the Milky Way. It rises out of the southeastern horizon just to the left (east) of the bright star Sirius in Canis Major (the Big Dog), and gradually diminishes in intensity as you follow it higher, passing between Orion (the Hunter) and Gemini (the Twins), and higher, just beyond the horn tips of Taurus (the Bull).

The point in the evening sky that sits directly opposite our galaxy’s core is located four finger widths to the left (or 4.3° to the celestial northeast) of a moderately bright star named Alnath (or Elnath), which represents Taurus’ higher horn tip. That star is shared by the constellation of Auriga (the Charioteer). In the rough ring of stars that form Auriga, Alnath sits opposite the very bright, yellow star Capella, which sits almost directly overhead at around 8 pm local time.

The Milky Way should be visually dimmest near Alnath – but it isn’t. That’s because our galaxy has a non-uniform structure of spiral arms wrapping around its central core, and also because dark gas and dusk randomly concentrated within the plane of the galaxy blocks starlight. In visible wavelengths, our Milky Way’s dimmest location is actually in the constellations next to Auriga – between Perseus (the Hero) and Camelopardalis (the Giraffe). Pictures show that dark dust darkens the Milky Way near Perseus’ brightest star, Mirfak.

To finish following the Milky Way across the winter evening sky, turn around and face northwest. In February, Perseus sits high in the northwestern sky, above the distinctive M- or W-shaped constellation Cassiopeia (the Queen). Cassiopeia will be dangling in an up-down orientation. The Milky Way is less intense here, but it builds in intensity again as we trace its thickening disk downward down through Cassiopeia and then lower, past her husband, Cepheus (the King). If your horizon is low and open, you might catch a glimpse of the bright star Deneb, which marks the tail of Cygnus (the Swan). Although much broader there, the Milky Way is darkened by a lot more dust and gas.

Many of the famous Messier List objects sit on or near the Milky Way. That is because they are composed of concentrations of stars (clusters) and gas (nebulae). But looking above and below the plane of the Milky Way (that’s to the left or right of it at this time of year), will reveal other cities of stars – separate galaxies far beyond our own. The brightest and easiest one to see is the great Andromeda Galaxy, also known as Messier 31. It is located only 15° (or 1.5 outstretched fist widths) to the lower left of Cassiopeia’s bottom half.

This week’s darker skies will also be ideal for exploring Taurus (which we toured here) and Orion (which was toured here.) Get out and enjoy the sights – if your skies are clear!

Valentine’s Night Treats

If you missed last week’s round-up of delightful Valentine’s-themed constellations, clusters, and nebulas – and even some heart-shaped craters on Mars, it’s here, with sky charts and some photos.

Binocular Comet Update

A relatively modest comet is traversing the northeastern evening sky this winter – and this week’s largely absent moon will allow observers in the Northern Hemisphere to continue watching it. The comet is named C/2017 T2 (PanSTARRS), after the robotic telescope that discovered it and the date it did so. It is currently shining at about magnitude 9 – well within reach of medium or large binoculars and backyard telescopes. It is conveniently positioned in the sky for evening viewing. It’s more than halfway up the northwestern sky after dusk – and then it drops lower in mid-evening as the Earth’s rotation carries the western sky lower.

During the week, the comet will move inside eastern Cassiopeia (the Queen). If you face northwest, the comet will be positioned 1.5 fist diameters to the lower right of the very bright star Mirfak in Perseus, and less than a palm’s width above (or 5° to the celestial west) of the medium-bright star Ruchbah in Cassiopeia. Ruchbah marks the top of the shorter peak of Cassiopeia’s “M”-shape, which will sit sideways in mid-evening.

Comets move past the background stars faster than the planets do. Over the next seven nights Comet C/2017 T2 Panstarrs will shift by about one finger’s width of sky, directly towards Polaris, which is three fist diameters to the right.

This week, the comet will also continue to sit a few finger widths to the lower right of the famous Double Cluster. That close-together pair of star clusters is visible to unaided eyes under dark skies and is very easy to see in binoculars from the city – making finding the comet very easy to find.

When viewed in binoculars and telescopes, Comet PanSTARRS will appear as a dim, fuzzy patch that might exhibit a faint greenish centre. Its modest tail should point roughly away from the Double Cluster. Let me know if you see the comet and if you see a tail! This comet is expected to brighten much more in the coming months. Stay tuned for updates!

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. On Wednesday nights they offer free public viewing through their rooftop telescopes, including their brand new 1-metre telescope! If it’s cloudy, the astronomers give tours and presentations. Registration and details are here.

On Tuesday, February 18 at 6 pm at Halo Express Bar in Mississauga, the Royal Canadian Institute for Science will present Dr. Bhairavi Shankar, a Planetary Scientist and founder/CEO of Indus Space presenting a free public talk entitled Exploring Earth & Beyond. Details and Eventbrite registration is here.

On Saturday, February 22 at 2:30 pm at the Brentwood Library, talented astro-photographer Michael Watson will present a free public talk entitled Under Southern Skies, featuring his amazing imagery from down under. Details and Eventbrite registration is here.

On Sunday, February 23 at 2 pm at J.R.R. Macleod Auditorium at U of T, the Royal Canadian Institute for Science will present John Donohue from the University of Waterloo’s Institute for Quantum Computing, presenting a free public talk entitled QUANTUM + Pop Culture. Details and Eventbrite registration is here.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!