A Peek at Polaris, the Waxing Moon and Dim Mars Duo in Evening, and the Equinox Arrives with a Lunar X!

This image of the waxing crescent moon was taken by Michael Watson of Toronto on March 2, 2014. It nicely shows the Earthshine phenomenon, and the way the position of the lit crescent on the young moon at this time of year resembles the Cheshire Cat’s smile. Michael’s gallery of images are hosted on his Flickr page here.

Hello, Pi Day Stargazers!

Here are your Astronomy Skylights for the week of March 14th, 2021 by Chris Vaughan. Feel free to pass this along to your friends and send me your comments, questions, and suggested topics. You can also follow me on Twitter as @astrogeoguy! Unless otherwise noted, all times are expressed in Eastern Time. To subscribe to these emails please click this MailChimp link.

I can bring my Digital Starlab portable inflatable planetarium to your school or other daytime or evening event, or teach a session online. Contact me through AstroGeo.ca, and we’ll tour the Universe, or the Earth’s interior, together!

The waxing moon will re-appear in the evening sky this week. It will pass near Mars and Uranus and then reach first quarter and a late-afternoon Lunar X on the coming weekend. Spot Mars near Aldebaran in evening and the gas giant planets dancing with Mercury in the eastern pre-dawn sky. We end the week with the arrival of the equinox. Read on for your Skylights!

Daylight Saving Time

Did you adjust your clocks forward yet? Last week, I dove into Daylight Saving Time (or DST, for short). You can read it here

Happy March Equinox!

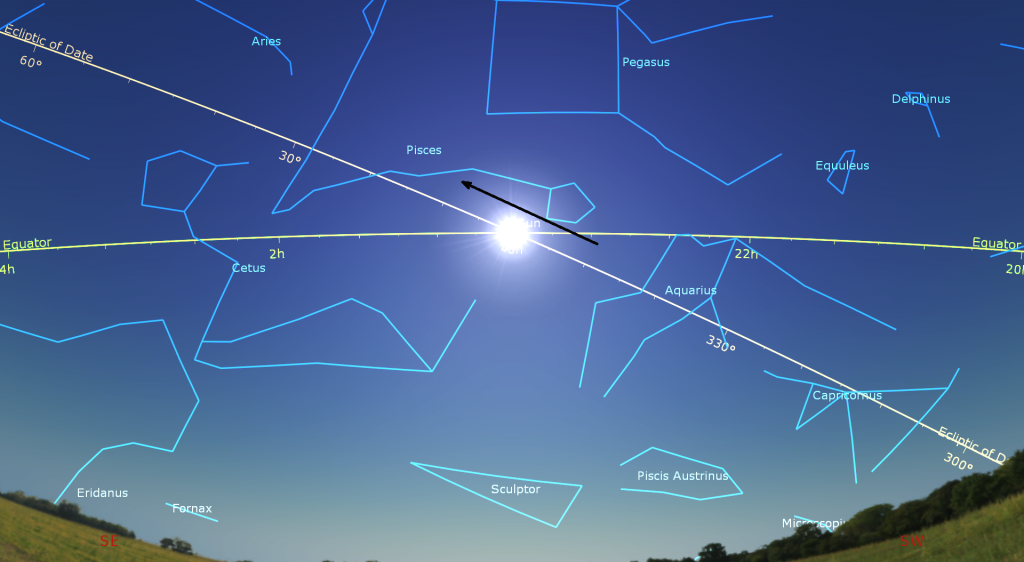

On Saturday, March 20 at 9:37 GMT (or 5:37 am EDT), spring will officially arrive in the Northern Hemisphere! At that moment, the sun’s apparent motion eastward along the ecliptic will carry it cross the celestial equator and into the northern sky. (Of course, the sun isn’t moving – we are!) The astronomical term for this event is the Vernal Equinox, where “vernal” is Latin for “spring”. I prefer to say March Equinox because autumn will commence for everyone in the Southern Hemisphere on that same day. The hemispheres will trade fall for spring again at the September or Autumnal Equinox.

On each of the two equinoxes, the world experiences about 12 hours each of daylight and darkness (it varies by latitude). This is where the word equinox (Latin for “equal night”) comes from. The March Equinox produces several interesting effects. For the following six months, the sun will spend more than 50% of each day shining overhead of the lucky folks in North America, Europe, and Asia! More time above the horizon for the sun means warmer air and longer daylight hours! At the same time, folks in the Southern hemisphere have to accept shorter, colder days and longer nights. (Warmly dressed astronomers don’t mind long winter nights!)

The amount of daylight increases fastest around the equinox. With the sun setting about 1.5 minutes later every night and rising about 1.5 minutes earlier every morning, each day has three more minutes of daylight than the day before. Conversely, the amount of daylight decreases by about three minutes per day around September 20. The day/night ratio changes extremely slowly around the winter and summer solstices in December and June, respectively.

The period around the equinoxes also offer increased odds of seeing the aurorae at both high northern and southern latitudes. Just as two bar magnets lined up with their poles in the same direction repel one another strongly, the Earth’s magnetic field repels the sun’s field. At the equinoxes, the Earth’s axis is tilted neither towards nor away from the sun, so the two “magnets” aren’t as parallel, reducing Earth’s ability to repel the sun’s field – and the charged particles that trigger aurorae in our upper atmosphere. I wrote a more detailed post on this topic with diagrams here.

It’s highly likely that St. Patrick’s Day, now observed annually on March 17, arose after the early Christian Catholic church converted pre-existing Celtic celebrations already being observed at the Equinox to a church feast day. It drifted away from the typical equinox date because of inaccuracies in the Julian calendar. I’ll be discussing this and other connections between world religions and astronomy during this week’s free Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy session! You can join us on Zoom here.

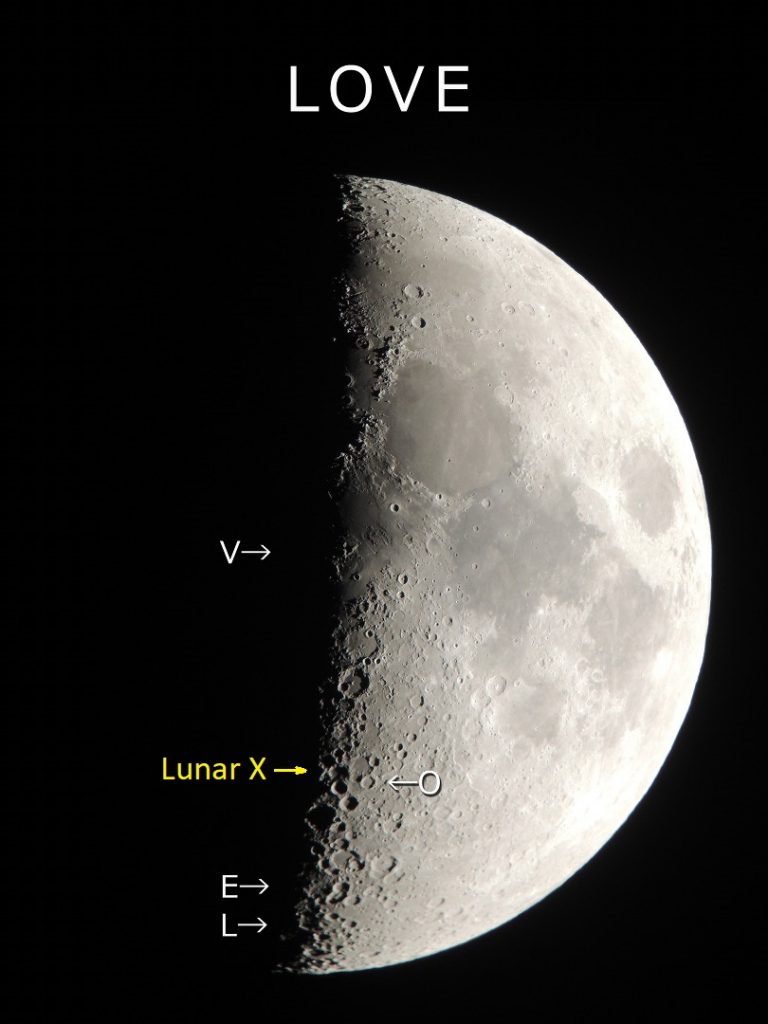

Lunar X and L-O-V-E

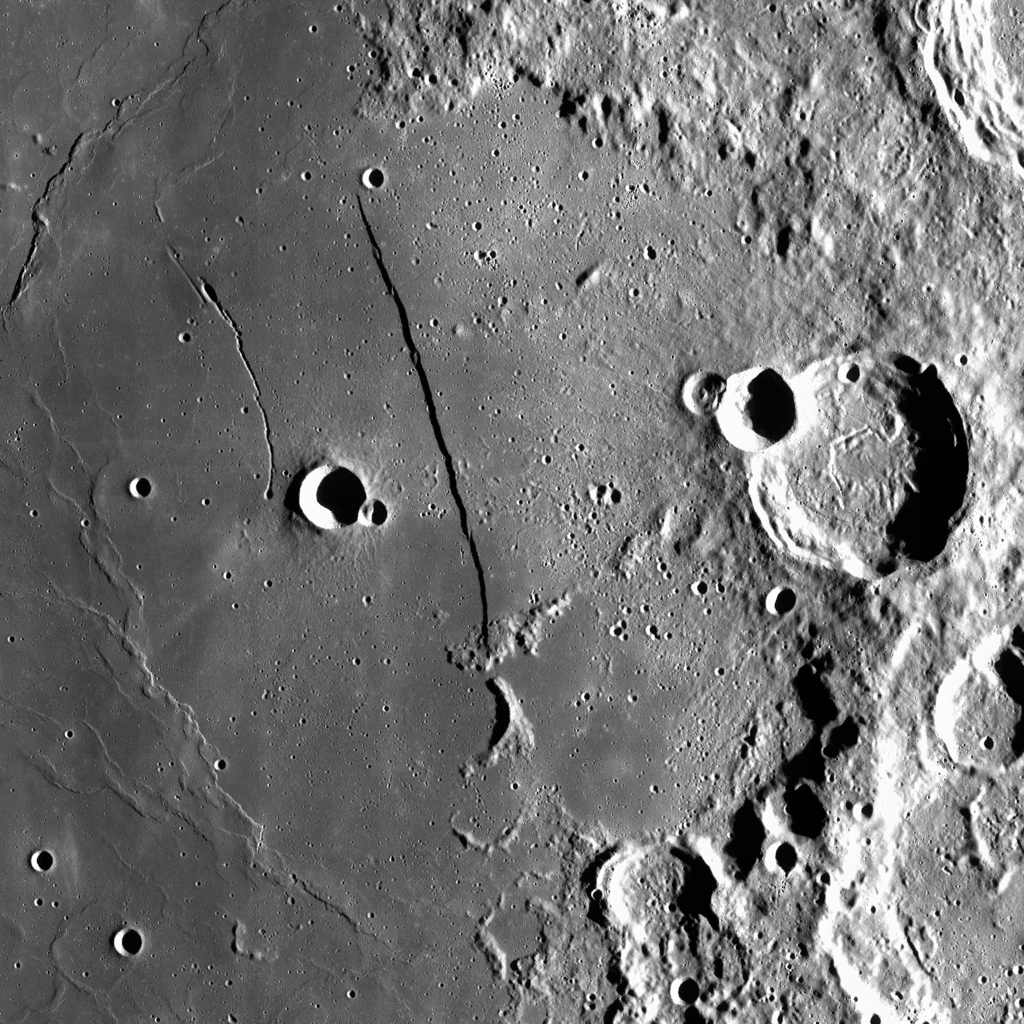

Several times a year, for a few hours near its first quarter phase, a feature on the moon called the Lunar X becomes visible in strong binoculars and backyard telescopes. When the rims of the craters Purbach, la Caille, and Blanchinus are illuminated from a particular angle of sunlight, they form a small, but very obvious X-shape. The phenomenon is an example of pareidolia – the tendency of the human mind to see familiar objects when looking at random patterns. The Lunar X is located near the terminator, about one third of the way up from the southern pole of the Moon (at lunar coordinates 2° East, 24° South). A prominent round crater named Werner sits to its lower right.

When the sun’s light first touches those craters at about 5 pm EDT or 20:00 Greenwich Mean Time (GMT), the X will appear small and indistinct. For the Americas, the moon will be high in the southeastern sky – but the sky will still be bright. The X will peak in intensity at about 7 pm EDT, just as the sky is starting to darken in the Eastern Time Zone. After 9 pm EDT (or 01:00 GMT on Sunday, March 21) the X will disappear. By then, the moon will shine in a dark sky for Eastern Canada and the USA. Don’t forget that you can view the moon in your telescope during the daytime – as long as you take care not to aim the telescope anywhere near the sun. Tip: 3D glasses from the cinema will darken the sky and enhance the moon in daytime. Rotate the glasses until the sky is darkest – or pop out one of the plastic lenses and turn that while you hold it over the telescope eyepiece. (If you have a variable density moon filter, set it to maximum light transmission and then rotate the entire filter until the sky is darkest.)

The Lunar X visible anywhere on Earth where the moon is shining in a dark sky during the window of time I’ve listed. Simply adjust for your difference from those time zones. Observers in western Europe and Africa will have the darkest skies.

At the same time, you can look for the Lunar V and the Lunar L. The “V” is produced by combining the small crater named Ukert with some ridges to the east and west of it. It is located a short distance above the moon’s equator at lunar coordinates 1.5° East, 8° North. For a further challenge, see if you can see the letter “L” down near the moon’s southern pole. Its position is to the southwest of three prominent and adjoining craters named Licetus, Cuvier, and Heraclitus, which resemble a Mickey Mouse’s head shape. Some people claim they can see a letter-E on the moon during the Lunar X period, too. Then, by picking a round crater along the terminator to serve as the “O”, you can spell L-O-V-E! Let me know if you see them.

The Moon

Following yesterday’s new moon, our nearest neighbour will return to the evening sky for observers all over the world this week – filling up with light each night as it increases its angle from the sun. Tonight (Sunday), you can try and glimpse the extremely thin crescent moon shining within the western twilight after sunset, especially at about 7:30 pm local time. The up-down angle of the evening ecliptic will keep the lit crescent along the bottom of the moon – creating the Cheshire Cat’s smile effect, especially from Sunday to Tuesday.

Watch for Earthshine or the “Ashen Glow” this week, too. When sunlight reflects from Earth’s clouds and the shiny Pacific Ocean, it slightly illuminates and brightens the part of the moon’s disk that isn’t receiving direct sunlight. Some call this phenomenon “the old moon in the new moon’s arms”. The effect will return after the new moon in April and May.

Dust off your old telescope and use it to enjoy the new sights offered each night as the pole-to-pole terminator boundary that divides the moon’s lit and dark hemispheres migrates across the moon’s face. The zone along the terminator defines where the sun is rising on the moon. The sunlight there is nearly horizontal, so it floods peaks and crater rims with bright light and casts long black shadows to the lunar west of every feature, no matter how subtle.

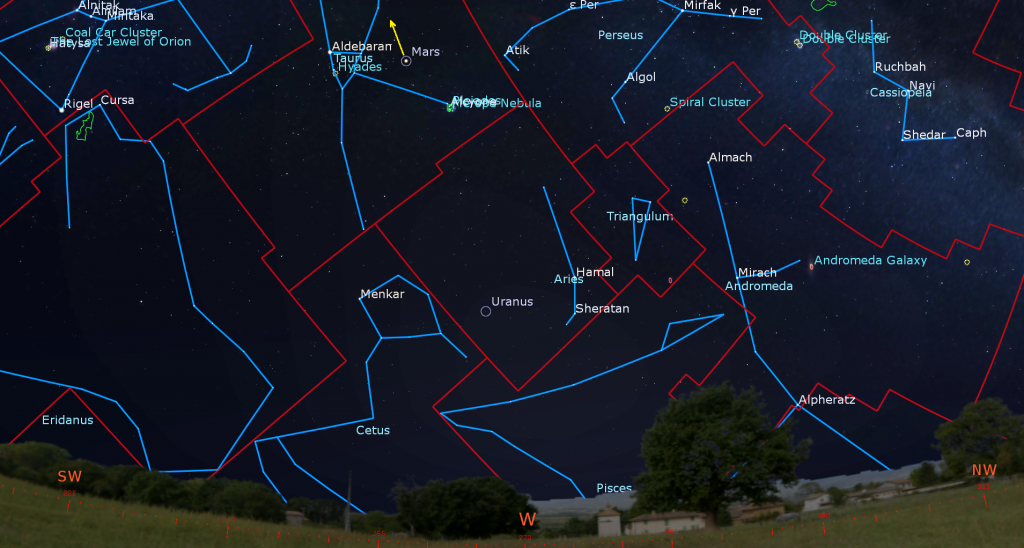

On Tuesday evening the crescent moon will be positioned several finger widths to the lower left (or 3.5 degrees to the celestial southwest) of the planet Uranus – allowing the moon and the magnitude 5.8 planet to share the field of view in binoculars. Normally, visits by the moon make seeing Uranus harder – but the 12%-illuminated moon won’t be excessively bright this time.

On Thursday night, the moon will land within the boundaries of Taurus (the Bull). The following night, look for the reddish, medium-bright dot of Mars shining several finger widths to the lower right (or 3 degrees to the celestial northwest) of the moon – close enough to appear together in the field of view of your binoculars. The bright little Pleiades star cluster will be situated a fist’s diameter to the moon’s lower right, too.

Between this Friday and next Monday night, moon will cross through the giant Winter Hexagon asterism, composed of the bright stars composed of the brightest stars in the constellations of Canis Major, Orion, Taurus, Auriga, Gemini, and Canis Minor – specifically Sirius, Rigel, Aldebaran, Capella, Castor & Pollux, and Procyon. After dusk, the huge pattern will stand upright in the southern sky – extending from 30 degrees above the horizon to overhead.

Saturday afternoon/evening will bring the Lunar X (see above). The moon will complete the first quarter of its orbit around Earth at 10:40 am EDT (or 14:40 GMT) on Sunday morning. At first quarter, the relative positions of the Earth, sun, and moon will cause us to see a half-illuminated moon – on its eastern side.

On Sunday night, the moon will be passing among the stars that form the toes of Castor in Gemini (the Twins), and the terminator will fall just to the left (or lunar west) of Rupes Recta, also known as the Lunar Straight Wall. The feature is very obvious in strong binoculars and any sized telescope. The rupes, Latin for “cliff”, is a north-south-aligned fault scarp that extends for 110 km across the southeastern part of Mare Nubium – that’s the large, dark region located in the lower third of the moon’s Earth-facing hemisphere. The Straight Wall is always prominent a day or two after first quarter, and shows up again just before third quarter. For reference, the Straight Wall is located above (to the lunar north) of the bright, prominent crater Tycho.

The Planets

It’s been really fun to see how much Mars resembles the nearby, slightly brighter, reddish star Aldebaran recently! Once the sky has darkened this week, find two medium-bright, reddish “stars” positioned about halfway up the southwestern sky. Mars is the one sitting about a palm’s width to the right (or 8 degrees to the celestial north) of slightly brighter Aldebaran, the star that marks the Bull’s southerly eye. Each night Mars’ eastward orbital motion will lift it higher compared to Aldebaran. By next Sunday night, Mars will be to Aldebaran’s upper right – orbital mechanics in action! In a telescope, Mars will show a very small ruddy disk. Observe it as soon as you can spot it, while it’s higher. It’ll be setting in the west at about 1:30 am local time.

Distant Uranus is the other planet currently available to view during evening. It’s quite easy to see in binoculars and backyard telescopes – if you know where to look – but the later sunsets of March are limiting the amount of dark sky time for viewing it. Uranus is positioned roughly midway between the medium-bright stars Sheratan in Aries (the Ram) and Menkar in Cetus (the Whale). Those two stars are 2.3 fist diameters apart, left-to-right, in the lower third of the western sky after dusk. Try to view Uranus early, when it’s higher in the sky and shining through less of Earth’s distorting atmosphere. In a telescope, Uranus will resemble the stars around it – but the planet won’t twinkle as much as they do, and it will show a blue-green colour.

Saturn, Jupiter, and Mercury will continue their grouping in the southeastern pre-dawn sky this week. The gas giant planets are each rising a little earlier each morning, allowing them to shine in a dark sky before dawn. Saturn clears the horizon at 5:45 am local time. Much brighter Jupiter joins it, a fist’s diameter to Saturn’s lower left (10 degrees east), about 30 minutes later. If you have a low and cloud-free horizon, you might even spot speedy Mercury to Jupiter’s lower left (east) after it rises just before 7 am local time. Try for Mercury on the first available morning. The planet will be traveling sunward and will move out of sight before week’s end.

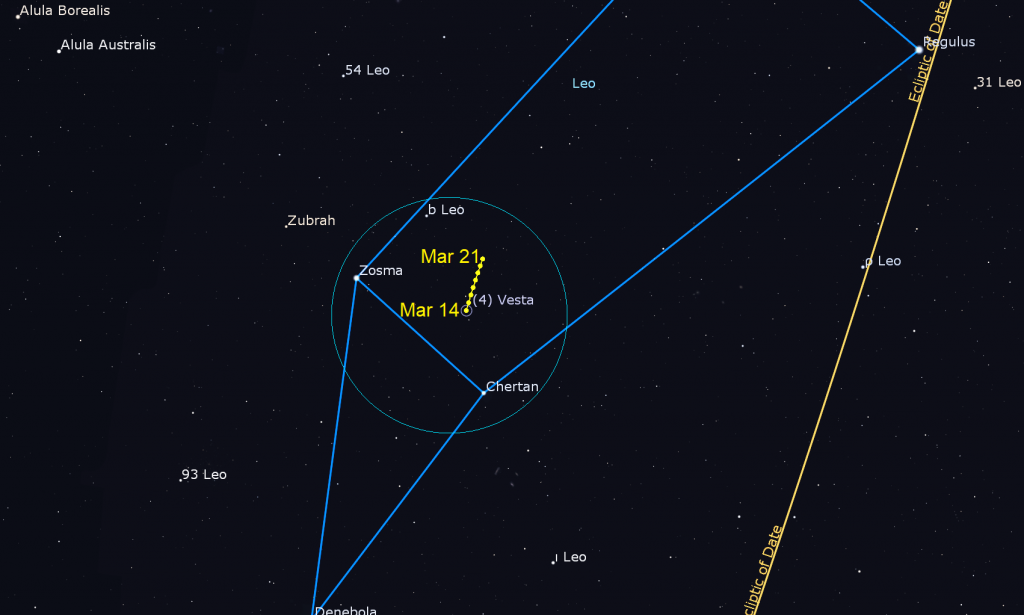

You still have a good opportunity to see the main belt asteroid designated (4) Vesta. At magnitude 5.8, it’s well within reach of your unaided eyes from a dark sky location, and in binoculars and small telescopes from the suburbs. Vesta is in the eastern evening sky in Leo (the Lion), approximately two finger widths above (or 2.5 degree to the northwest) of Chertan, the bright star that marks the lion’s rear haunches. Vesta will spend this week shifting above and between Chertan and the medium-bright star Zosma, the star delineating the lion’s backside.

Pointing at Polaris

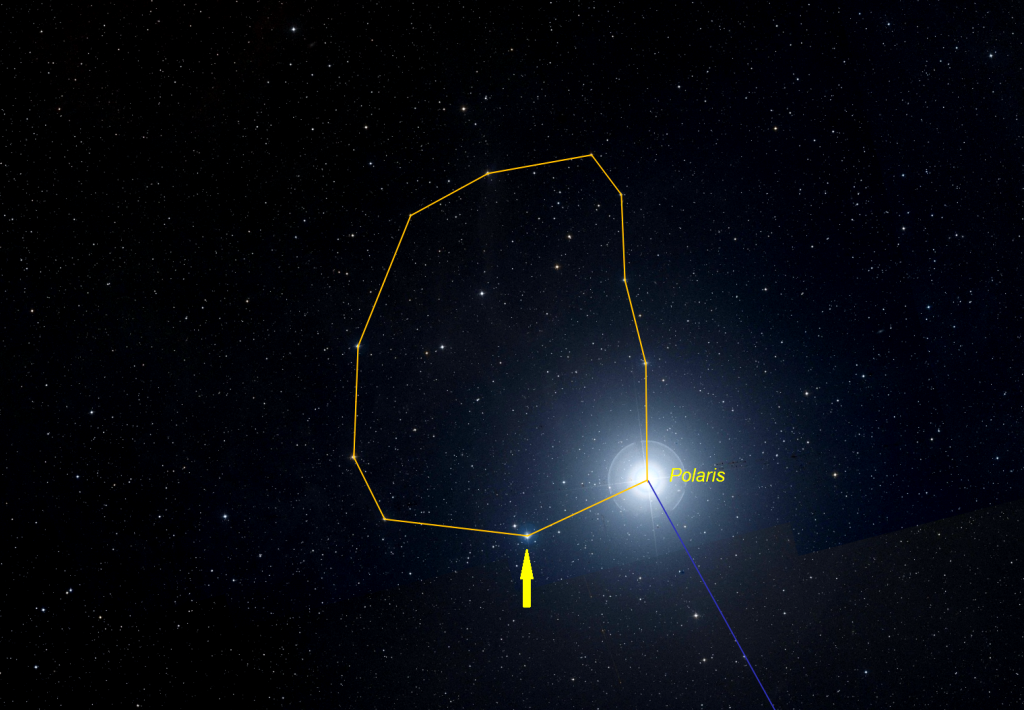

Polaris, the North Star, is the star at the tip of the handle of the Little Dipper asterism. We also know those seven stars as the constellation Ursa Minor (the Little Bear). Contrary to popular opinion, Polaris is not a prominent star at all. It is ranked only 48th in brightness. Polaris is located about 430 light-years from Earth. Its surface temperature is similar to our sun’s, but the star is much larger, and it emits 2500 times more light than our sun.

Polaris’ fame is due to its steadfast position over the northern horizon. While the rest of the sky revolves due to Earth’s rotation, Polaris remains anchored in place because it sits less than a finger’s width from the North Celestial Pole (or NCP, for short), the imaginary point in space that the Earth’s axis of rotation points toward. Due to precession, the slow wobble of the Earth’s axis, Polaris will slowly drift even closer to the NCP until the year 2101. The star Thuban in Draco (the Dragon) was the pole star when the pyramids were built. Starting in 2000 years, several stars of Cepheus (the King) will take turns as Earth’s Pole star.

You can measure your latitude on Earth by counting how many degrees above the horizon Polaris is. Combine that knowledge with the fact that Polaris marks where the compass direction of north is, and you’re well on your way to figuring out your location on Earth – at least, that’s what folks did before GPS!

Polaris can easily be spotted with mere eyeballs in a moderately dark sky – if you know where to look. The easiest way to find Polaris is to use the outermost stars in the Big Dipper’s bowl. The dipper is standing upright on its handle in the northeastern sky during evening in March. Join an imaginary line from Merak (the bottom of the bowl) to Dubhe (at the rim of the bowl) and keep going. Polaris is the next obvious star you’ll come to. It’s about three fist diameters away from Dubhe. Don’t forget that the Big Dipper, like everything else in the sky, circles around Polaris continuously. During some parts of the year you’ll be drawing that line upwards, and at other times toward the left or the right. Merak and Dubhe are often referred to as the Pointers.

In mid-March at around 9 pm local time, the rest of the Little Dipper extends sideways and down to the right from Polaris, and then curls upwards towards the Big Dipper. The two dippers fall on either side of the tail stars of Draco (the Dragon). The magnitude 2.06 star at the outer edge of the Little Dipper’s bowl (and closest to the Big Dipper) is named Kochab. This K-class, reddish star is slightly fainter than Polaris. The other five stars of Ursa Minor may be too dim to see from the city with unaided eyes, but binoculars will reveal them.

If you have a telescope, aim it at Polaris and look for a dim, white-coloured partner star sitting close to yellowish Polaris. As before, the rotation of the sky can place that little star anywhere on a circle surrounding Polaris. On mid-March evenings, it will be to Polaris’ lower left, but your telescope’s optics will probably flip and/or mirror it to another orientation. You can connect that little star with a number of other stars to form a small, roughly circular ring a finger’s width across. It’s on the side of Polaris opposite to Kochab. It’s called the Engagement Ring, and Polaris is the diamond. Let me know if you see it!

Gemini and Other Winter Constellation Treats for Dark Nights

If you missed my detail tour of Gemini (The Twins) last week, I posted it here.

Public Astro-Themed Events

Every Monday evening, York University’s Allan I. Carswell Observatory runs an online star party – broadcasting views from four telescopes/cameras, answering viewer questions, and taking requests! Details are here. Their in-person Wednesday night viewing has been converted to online via the observatory YouTube channel, where they offer free online viewing through their rooftop telescopes, including their 1-metre telescope! Details are here.

My free, family-friendly Insider’s Guide to the Galaxy webcasts with Jenna Hinds of RASC National returns on Tuesday afternoon, March 16 at 3:30 pm EDT. We’re going to talk about how astronomy has influenced religious festivals and traditions! You can find more details, and the schedule of future sessions, here and here.

On Wednesday evening, March 17 at 7:30 pm EDT, the RASC Toronto Centre will live stream their monthly Speakers Night meeting. This month will feature Dr. Nienke van der Marel, Banting Fellow, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Victoria. Her talk is entitled Planets under construction; how to study a million year process. Everyone is invited to watch the presentation live on the RASC Toronto Centre YouTube channel. Details are here. The RASC Toronto Centre has an archive of their past meetings and guest lectures on their YouTube Channel here.

On Sunday afternoon, March 28 from 1 to 2 pm EDT I’m hosting an online session for RASC called Ask an Astronomer! We’ll explore the night sky together and answer your astronomy and space-related questions in simple language – using pictures, illustrations and planetarium software. The deadline to register is Friday, March 26 at 3:00 pm. Registration is here. A modest fee goes to support our ongoing efforts to deliver public programs at DDO.

Keep looking up, and enjoy the sky when you do. I love questions and requests. Send me some!